Composition Forum 45, Fall 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/

Importing and Exporting across Boundaries of Expertise: Writing Pedagogy Education and Graduate Student Instructors’ Disciplinary Enculturation

Abstract: This article reports survey and interview research on how graduate student instructors (GSIs) across the United States navigate the boundaries of disciplinary expertise that define their work as students and teachers. The disciplinary backgrounds of GSIs in this study influenced their experiences with formal writing pedagogy education and their teaching practices. GSIs imported content, mindsets, pedagogies, and skills and expertise from their home disciplines into the FYW classroom and exported practices and dispositions from FYW into their own work as graduate students. I suggest how writing pedagogy educators might reframe preparation experiences to recognize the disciplinary boundaries GSIs work across and to repurpose these boundaries as sites for richer professional development and writing instruction.

Most writing programs face the “intractable problem” of professionalizing teachers from disciplines outside writing studies (Wardle, “Intractable Writing Program Problems”). As a still emerging discipline experiencing “a disciplinary turn,” we are concerned now more than ever with pursuing clearly defined lines of research, developing our own majors and departments, and stratifying and disseminating our knowledge (Yancey). But many teachers of our most established course, first-year writing (FYW), do not have credentialed expertise in writing studies. Although Kristine Hansen has explored possible solutions to this lack of expertise (like undergraduate majors in writing and “paraprofessional” credentialing for writing teachers without degrees in writing), current budgets and constraints for most writing programs mean many will continue to employ nonspecialists (defined for the purposes of this article as those without advanced degrees in writing studies) to teach writing courses. Many of these teachers will be graduate student instructors (GSIs).

Ray Kytle noted as early as 1971 that employing nonspecialists as writing instructors reinforces “the condescending notion that ‘anyone can teach the course,’ that teaching it well requires no special interest, no real commitment, no specialized knowledge” (341). How can writing program administrators (WPAs) employ and prepare nonspecialists to teach FYW without feeding the marginalization of our disciplinary expertise? How can they initiate GSIs who carry allegiances to other disciplines like literature and creative writing into the knowledge-base and practice of teaching writing? This article attempts to answer these questions in the context of what E. Shelley Reid has named writing pedagogy education or WPE (Preparing Writing Teachers): the preparation and professionalization experiences we provide new writing teachers, including courses in composition theory and pedagogy, summer boot-camps, in-service workshops, and so on. Catherine Latterell argues that our programs for preparing GSIs “are an especially important site of disciplinary formation [in writing studies] and have much to tell the field about how it reproduces itself and shapes its future” (8). Similarly, Sidney Dobrin argues that the ideologies and programmatic cultures created and reinforced by the composition practicums control, in part, “how and in what ways the very discipline of composition studies is perpetuated” (4). WPE invites new teachers to adopt, at least while teaching, the disciplinary knowledge, values, and expertise of writing studies, no matter their other disciplinary allegiances. This can lead to a fraught boundary-crossing experience for new teachers.

In what follows, I argue that WPE must account for disciplinary influences on how GSIs process their formal preparation and teach FYW. I share results of an empirical study examining how GSIs navigate disciplinary boundaries. I propose the language of “imports and exports” as a useful way of naming GSIs’ movement of disciplinary concepts across disciplinary boundaries: GSIs import knowledge from their home disciplines into their work as teachers in FYW and export knowledge from writing studies back into their work as students in their home disciplines. I examine how and why GSIs’ experiences with WPE and their practices as teachers are so influenced by their disciplinary backgrounds and allegiances. Finally, I explore how writing pedagogy educators might reframe preparation experiences to recognize the disciplinary boundaries GSIs work across and to repurpose these boundaries as sites for richer professional development and writing instruction.

Disciplinarity in the Teaching of Writing

Our field’s collective anxiety about our status as a discipline stems partially from our fraught history as a “teaching subject” and a service program with (presumably) no intellectual body of knowledge to offer. Historians of writing studies have chronicled the divisive perception of literary studies as a masculinized, professional, research-oriented endeavor focused on the creation of knowledge and writing studies as a feminized, teaching-oriented practice focused on the transmission of knowledge (Berlin 20-25; Crowley 54-58; Marshall 8; Schell 29-33). This history makes our field justifiably resentful of FYW’s stigma as undesirable service work among many of our colleagues in English departments. In cases where literature or creative writing graduates are unable to secure tenure-line positions in their primary areas of emphasis, they can, it is thought, always teach composition: “anyone in English is believed to be able to teach [FYW] at any university or college or community college or high school at any time. No specific credentials in rhetoric and composition are needed” (Zebrowski 80). Sharon Crowley notes that since many graduate students are awarded teaching positions based on their academic prowess (often in areas outside of writing studies), GSIs “may be uninterested in composition theory or pedagogy” (5).

In such a context, WPE can become a site of disciplinary tension, boundary crossing, and boundary reinforcement for WPAs and for new teachers. GSIs often resist their formal preparation in the teaching of writing (Ebest; Grouling; Hesse; Rankin) or have difficulty integrating their formal preparation into their actual practice (Brewer, Conceptions of Literacy; Estrem and Reid, What New Teachers; Reid, et. al.; Restaino). Indeed, WPE can even be experienced by new GSIs as an uncomfortable site of indoctrination or conversion (Dobrin; Welch), where experts in writing studies discipline novices into ideal ways of teaching. While WPE is a site of disciplinary friction and resistance, it is also often a site of disciplinary recruitment. Many scholars come to writing studies by way of teaching FYW, during and after graduate school, and the experiences and knowledge they bring with them from other disciplines and professions can enrich their work in writing classrooms. In this sense, employing nonspecialists as writing teachers may not be a bad thing. The existence of WAC/WID programs suggests the value and even the imperative of preparing nonspecialists to teach writing to undergraduates. Downs and Wardle have tempered their position that when we employ “nonspecialists to teach a specialized body of knowledge, we undermine our own claims as to that specialization” (Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions 575) and argue that preparation experiences could be designed to help nonspecialists “become familiar with the relevant content of writing studies, and to embrace that field as their own” (Reflecting Back). In implementing such preparation at the University of Central Florida, they acknowledged that “the varied backgrounds of our teachers bring a depth and richness to our program that we would not have had otherwise” (Reflecting Back). While varied disciplinary backgrounds can enrich our discipline, new teachers must still learn “the relevant content of writing studies.” Such learning may be more feasible for nonspecialists employed on longer-term contracts. But what does it mean for GSIs, many of whom will teach FYW for only a year or two before moving on to other professional endeavors? How can we help GSIs competently and quickly cross boundaries between their home disciplines and their work as teachers in writing studies?

Prior Knowledge and the Teaching of Writing

Researchers have made great strides in understanding how first-year students rely on and transfer prior knowledge as they learn to write (Bastian; Reiff and Bawarshi; Robertson, et al.; Rounsaville), but less research has explored how GSIs transfer disciplinary ways of knowing and doing from their home disciplines into their teaching of writing. It seems clear, however, that GSI resistance to WPE is often based in moments when formal preparation conflicts with graduate students’ prior knowledge and disciplinary training. Meaghan Brewer, for example, has insightfully explored how GSIs’ conceptions of literacy, based in disciplinary training or personal experience, shaped their teaching and their reception of WPE, sometimes in ways that perpetuated incomplete or elitist ideas (The Text Is the Thing; Conceptions of Literacy). All new teachers carry beliefs and proto-theories gained from personal experience in various disciplinary and professional settings (Brewer, Conceptions of Literacy; Dryer; Estrem and Reid, What New Teachers; Qualley; Reid et al.), and they “import” these ideas into their work as teachers. Donna Qualley has created a useful conceptual map of transfer research and how it might apply to GSIs’ use of prior knowledge: she identifies a complex terrain of prior knowledge, new knowledge, programmatic contexts, boundary crossing, remix, and so on. To synthesize their formal preparation in ways that improve their teaching, GSIs must explore “how prior knowledge complements and contradicts new learning” (Reid, On Learning to Teach). To help GSIs engage in this kind of exploration, we must understand how graduate students negotiate their knowledge of writing studies as a discipline—both as students and teachers—and the extent to which they rely on proto-theories and prior disciplinary experiences.

Background & Methodology

Tricia Serviss has called for writing studies researchers to “develop our research findings together rather than striving to do alone what none have done before” (5). Serviss and Sandra Jamieson further argue that “RAD research in writing studies ought to be continuously evolving rather than simply being reproduced and verified via replication” (28). Drawing from this methodological perspective, this study builds on research on GSIs by E. Shelley Reid and Heidi Estrem, with some modifications in target population and research instruments. My purpose was not simply to repeat but to expand their important findings. In 2012, Reid and Estrem reported in two articles on their multiyear, multisite study that examined how well GSIs incorporated their formal preparation into their practice as teachers (Reid et al.; Estrem and Reid). Their survey and interview research found that integration was present but uneven and that formal WPE is just one “among multiple streams of influences, cultural models and expectations, and experiences that new instructors are negotiating” (Estrem and Reid 476). They also reported that the GSIs in their study “were influenced more strongly by prior personal experiences and beliefs and their experiences in the classroom than by their formal pedagogy education” (Reid et al. 34), and called for more data-driven research on the effects of WPE on GSIs (62-63). Although Reid and Estrem found few differences among their study population of master’s students in their first, second, or third year of teaching across two sites, they suggest that “a survey that included larger numbers overall, larger numbers of beyond-first-year TAs, TAs with a wider range of educational foci, and/or TAs with more experience (four, five, or six years in the classroom) might have revealed more points of divergence” (Reid et al. 54).

My research responds to their call and extends their study in two specific ways: a broader survey population (including GSIs from across the United States in both master’s and doctoral-level programs) and an examination of how disciplinary allegiance (or what Reid et al. call educational foci) informs GSIs’ teaching and their reception of WPE.

Research Design

In designing survey and interview protocols, I drew on questions from Reid et al. with some additions and modifications (see Reid et al.’s original questions in their referenced article; see Appendix 1 for this study’s survey protocol and Appendix 2 for this study’s interview protocol). The purpose of both the survey and interview protocols was to determine which formal and informal preparation experiences GSIs found to be most helpful, what resources GSIs imported into and exported out of the FYW classroom, and how disciplinary allegiances influenced these factors.

After receiving IRB approval,{1} I distributed the survey through an email to the Writing Program Administration—Listserv, the WPA Graduate Organization Facebook page, and through individual emails to 64 writing program administrators (WPAs) in a variety of programs across the United States. The survey invited GSIs to participate in a follow-up interview. Follow-up interviews provided thicker description of GSIs’ experiences.

Participants

Survey respondents totaled 132 graduate instructors; 24 participated in follow-up interviews. Table 1 shows the breakdown of survey and interview participant characteristics. Interview participants were generally representative of the total survey participants.{2} Graduate students in this study were predominantly white females in their 20s who spoke English as their native language. These demographics are roughly representative of the larger population of graduate students in English departments. The American Academy of Arts & Sciences reports that in 2014, only 15% of master’s degrees in English Language and Literature (ELL) were awarded to racial/ethnic minority students and only 10% of doctoral degrees were awarded to racial/ethnic minority students. They also report that women earned 66% of master’s degrees and 60% of doctoral degrees in ELL in 2014 (Racial/Ethnic; Gender). These demographics also reflect what other scholars have already noted about the lack of racial diversity in composition studies (Inoue, Friday; Kynard). The present study did not ask GSIs specifically about how identity markers like race and gender (either their own or their students’) influenced their approaches to teaching writing and participant comments also did not center on these concerns. Future research might explicitly examine the impact of identity markers like race and gender on GSIs’ relationship to disciplinarity, WPE, and teaching.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics

|

Participant characteristics |

Survey participants (N = 132) |

Interview participants (N = 24) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age (years) |

61% (81) 20-29 25% (33) 30-39 14% (18) 40+ |

63% (15) 20-29 16% (4) 30-39 21% (5) 40+ |

|

Gender |

71% (93) female 27% (36) male 2% (3) other gender identity |

67% (16) female 29% (7) male 4% (1) other gender identity |

|

Racial/ethnic identity |

85% (112) White 1.5% (2) Black or African American 1.5% (2) Asian 6% (8) Hispanic/Latino 6% (8) other racial/ethnic identity |

79% (19) White 4% (1) Asian 8.5% (2) Hispanic/Latino 8.5% (2) other racial/ethnic identity |

|

Native language |

97% (128) English 3% (4) other language |

96% (23) English 4% (1) other language |

|

Degree type |

50% (66) PhD 11% (14) MFA 36% (48) MA/MS 3% (4) other (combined MA/PhD, MAT, MPP, etc.) |

63% (15) PhD 13% (3) MFA 16% (4) MA/MS 8% (2) other (combined MA/PhD, MPP) |

|

Field of study |

39% (51) literature 34% (45) rhet/comp 16% (21) creative writing 11% (15) other (TESOL, tech comm, education, comparative studies, public policy, etc.) |

29% (7) literature 25% (6) rhet/comp 13% (3) creative writing 33% (8) other (TESOL, tech comm, education, comparative studies, public policy, etc.) |

|

Experience teaching FYW |

39% (51) in first semester 36% (48) taught 2-6 semesters 25% (33) taught 7+ semesters |

42% (10) in first semester 33% (8) taught 2-6 semesters 25% (6) taught 7+ semesters |

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis. I used cross-tabulations to examine how subsets of the survey population differed in rating the helpfulness of various preparation experiences for building teacher skills, confidence, and problem-solving ability. The scale was 1-5 with 1 being “didn’t help much at all” and 5 being “helped quite a lot.” If GSIs had not encountered a particular experience, they were asked to select “0.” In analyzing the quantitative Likert scale data, I removed all “0” answers. The remaining data were collapsed into three response points: helpful (4’s and 5’s), neutral (3), and not helpful (1’s and 2’s). The quantitative data are reported by percentage of responses in each of these three categories.

Qualitative Analysis. In analyzing the qualitative data, I employed constant comparison to identify relevant themes in GSIs’ responses. In analyzing both survey and interview responses, I first read through all responses, looking for general patterns. I then reviewed the data again, this time developing categories for how GSIs described disciplinary impact on their experiences as teachers. At this stage, some responses were discarded because they were too vague to categorize (examples include answers such as “n/a” or “to be determined”). After developing initial categories, I returned to the data, narrowing and combining categories into the codes described below. I employed peer debriefing and member reflections to ensure the quality of the data.

Results

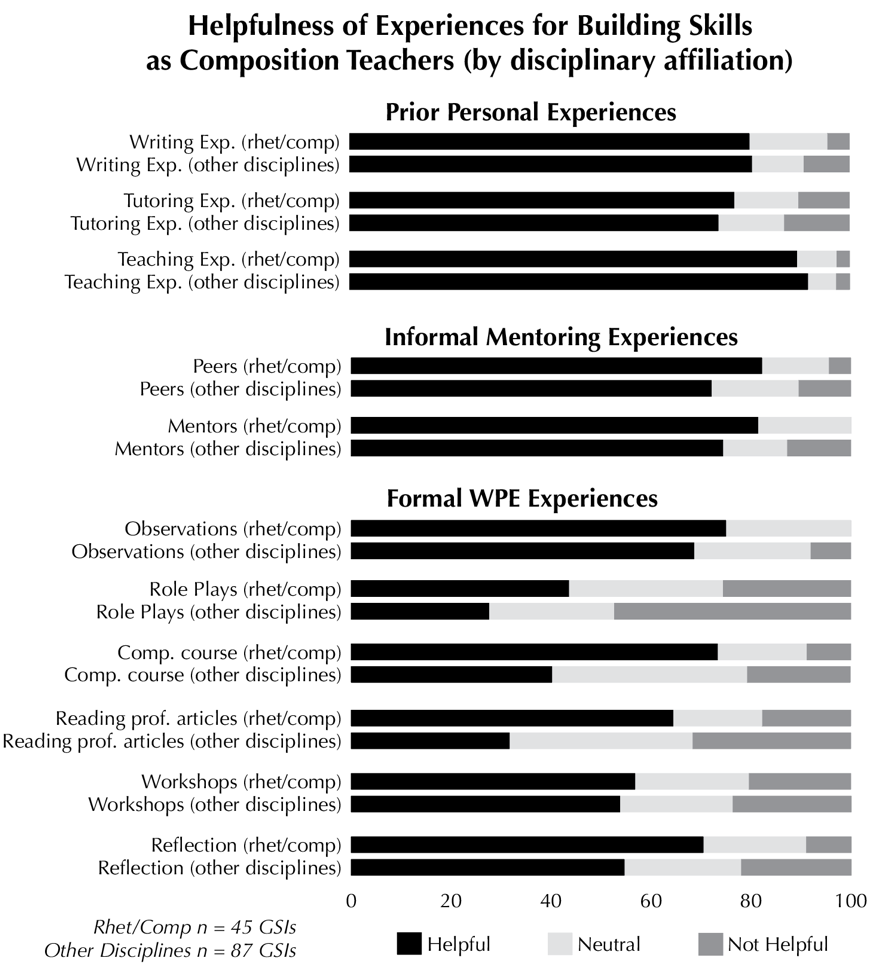

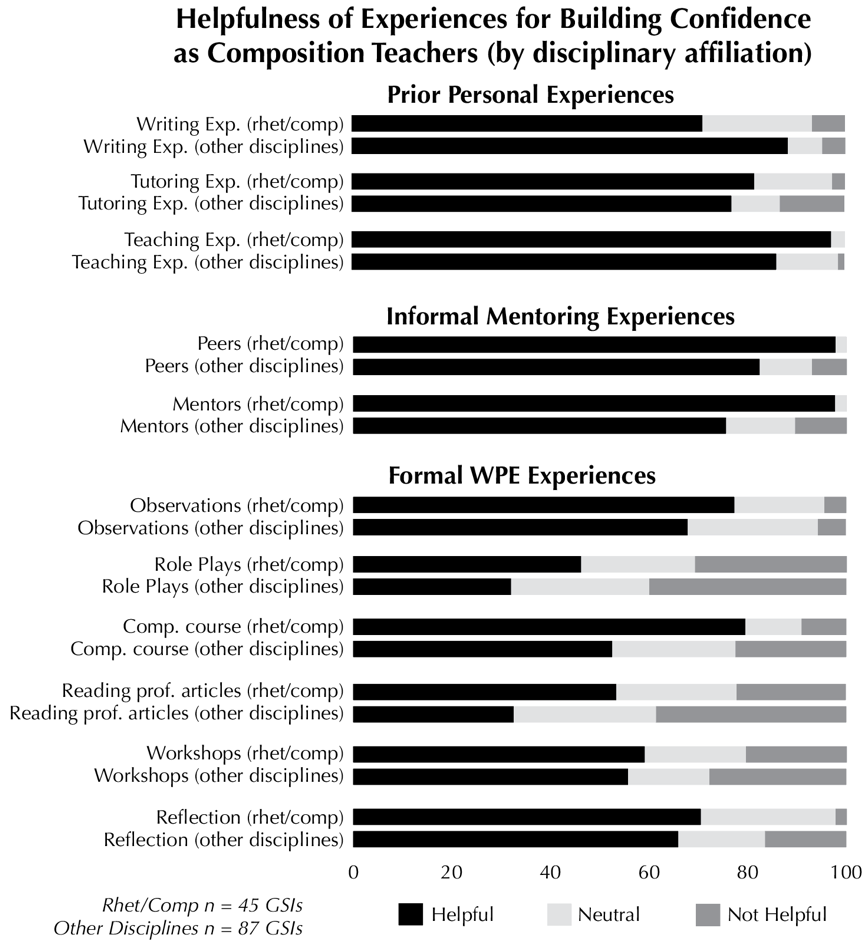

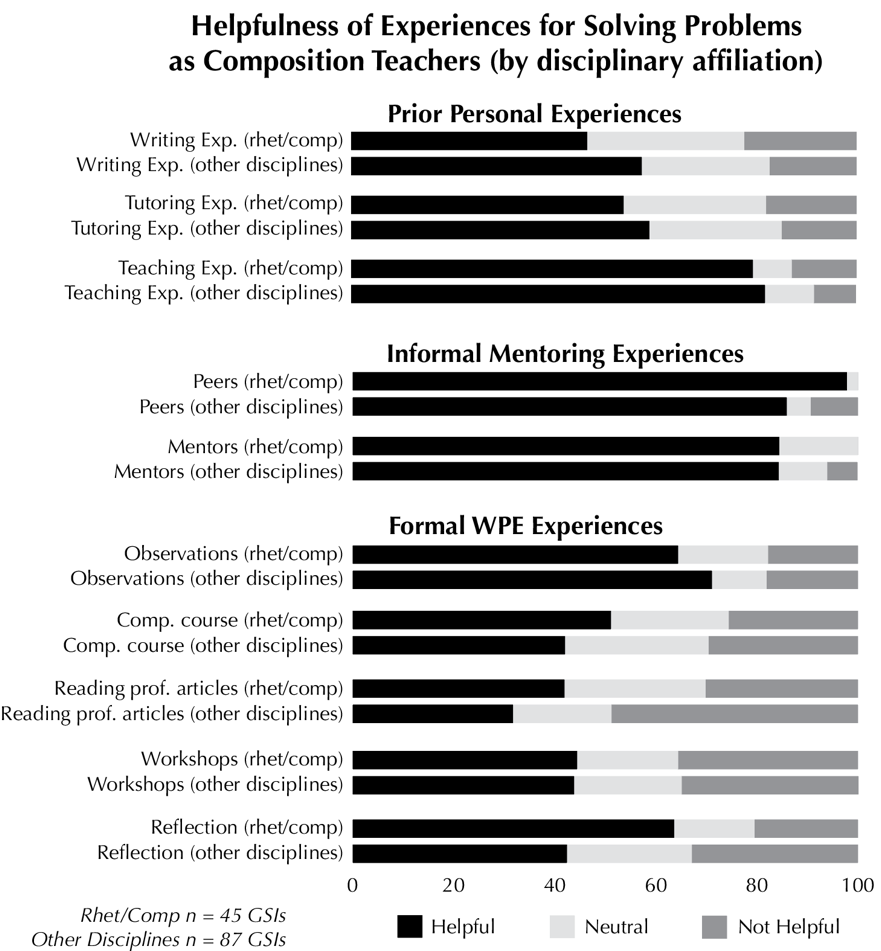

Generally, my survey results reinforced Reid et al.’s findings: participants in both their study and mine found formal WPE experiences (like the composition practicum/theory course, role-plays, reading professional articles, and reflective writing/thinking) less helpful for building their skills, confidence, and problem-solving ability as writing teachers than informal preparation (like personal experiences as writers, tutors, and teachers and exchanges with peers).

Reid et al. also found generally steady results for first-year, second-year, and third-year GSIs. Analysis of GSIs in my survey population found minimal but notable differences in novice (1 or 2 semesters taught) and experienced (7+ semesters taught) GSIs. Encouragingly, GSIs who had taught for seven or more semesters seemed to value their composition practicum/theory course and reading professional articles slightly more than first-semester GSIs for building their skills. This may be because experienced GSIs have more time to participate in and reflect on their formal preparation as they move beyond the first year of teaching; as a result, they may see better how these formal experiences apply to the classroom. First-semester GSIs valued classroom observations to problem-solve more than their more experienced counterparts. In general, however, years of experience seemed less influential than disciplinary affiliation on GSIs’ perception of the helpfulness of preparation experiences.

Disciplinary Differences in How GSIs’ Valued WPE Experiences

Although all GSIs, regardless of disciplinary affiliation, valued informal experiences above their formal WPE, GSIs studying in disciplines other than rhetoric and composition appear to hold even less value for formal experiences, particularly those formal experiences focused on disciplinary knowledge: taking the composition practicum/theory course and reading professional articles. Figures 1-3 demonstrate these results for how helpful GSIs ranked experiences in building their skills, confidence, and problem-solving ability as writing teachers.

Figure 1. Percentage of GSIs rating various experiences as helpful in building their skills as composition teachers, compared by disciplinary affiliation

Figure 2. Percentage of GSIs rating various experiences as helpful in building their confidence as composition teachers, compared by disciplinary affiliation

Figure 3. Percentage of GSIs rating various experiences as helpful in solving problems as composition teachers, compared by disciplinary affiliation

Why do GSIs in rhetoric and composition and GSIs in other disciplines value their formal preparation differently? Composition pedagogy/theory courses and professional articles may of course feel more pertinent to rhetoric and composition GSIs’ academic studies than it is to literature or creative writing students’ studies. But the survey question asked about the effect of these courses and readings on GSIs’ confidence, skills, and problem-solving ability as writing teachers and not the effect on their graduate studies. Carrying a disciplinary allegiance to writing studies seems to increase participants’ value of these experiences for their work as writing teachers. My survey did not ask participants to explain the reasoning behind their responses, making it is hard to know exactly why this discrepancy exists. Qualitative data (discussed in further detail below) suggest two possibilities: 1) many GSIs trusted strongly in their own prior experiences as writers even when those experiences countered disciplinary knowledge in writing studies, and 2) many GSIs struggled to know how to apply theoretical knowledge about writing to their practical classroom work. It is possible that GSIs in rhetoric and composition, who purposefully come to graduate school to study writing, may be more open to questioning prior knowledge and adopting new knowledge about writing.

Disciplinary Imports & FYW Exports

In open response survey questions, participants were asked what concepts (ideas, theories, scholarly literature, disciplinary practices) imported from their home disciplines shaped their approach to teaching FYW and what concepts exported from FYW influenced their own research and writing practices as graduate students.

Disciplinary Imports

Imports refer to what GSIs brought with them from their home disciplines into the FYW classroom. Participant responses fell into five central categories: GSIs imported content, mindsets, pedagogies, and skills or expertise, or they reinforced the boundaries between their home disciplines and FYW by keeping their home disciplines separate from their work in FYW. Because this question was displayed only to participants who indicated that their primary area of study was outside of rhetoric and composition, only 71 participants responded. Original capitalization and punctuation have been retained in quoted responses.

Content (19 respondents). GSIs imported specific content from their home disciplines that they taught explicitly in the FYW classroom. Literature GSIs described bringing in literary texts from their areas of focus as examples of effective writing, while creative writing GSIs similarly assigned exemplary creative nonfiction or fiction texts for their students to read. Some brought in concepts but not texts: a GSI in medieval literature covered “some of the history of English concepts to ‘explain’ why we write the way we do,” while a GSI who had studied law taught the “structures used in appellate arguments” to help students write speeches. When GSIs imported content from their home disciplines, they typically adapted the content to connect it more clearly to FYW and help students recognize transferrable elements of writing. For example, one participant shared,

I try to bring in my own field of knowledge as much as possible. For one thing, I want my students to see how Writing and Rhetoric transfers to any subject. I will often give them examples of portions of my thesis and how I am utilizing (or not utilizing) what we are learning. As an Early Modern Lit student, I will often talk about how Renaissance Scholars considered everything to be an argument. We will discuss Logos quite a bit in regards to this Renaissance type of thinking. I also bring Shakespeare in often in order to teach paraphrase, style, and introductions.

Importing content allowed GSIs to make their own studies relevant to the FYW classroom and to keep class “interesting” and “engaging” for themselves and their students.

Mindsets (25 respondents). Mindsets referred to responses describing specific ways of seeing, theorizing, and doing based on disciplinary training, allegiance, and identity. Mindsets affected how instructors approached their teaching without leading them to explicitly import content. For example, a creative writing GSI wrote, “probably that i identify first and foremost as a poet has shaped the approach that we should just be writing, simply, and writing about things we can touch, that are around us, about ourselves, and addressing issues that affect us.” Another GSI shared, “I am studying community development, which focused on issues of power and privilege quite a bit. Because of that, I draw heavily on Paulo Freire’s focus on empowerment.” Some responses in this category were stated as guiding principles: “writing is a personal and identity building process” (literature PhD student); “writing is exciting, a way to express yourself and figure out what you think” (creative writing MFA student); “storytelling is the best mode for communicating” (literature PhD student); “too much focus on grammar can make a writer resistant to both writing and to the Instructor” (linguistics MA/PhD student); “the idea of classroom as a community (Lave and Wenger and sociocultural theory in general) compels me to teach in a way that honors my students’ humanity and their communities” (education PhD student). These disciplinary ways of theorizing represented foundational values that shaped GSIs’ mindsets about what and how they should teach students. Mindsets are reminiscent of Brewer’s idea of conceptions of literacy as “persistent” prior beliefs based in personal experience and disciplinary background that influenced “what got taught in individual composition courses” (Conceptions of Literacy 26). To ensure these imports serve FYW students well, WPE might encourage GSIs to identify, articulate, and understand how these mindsets influence their actual classroom practice.

Pedagogies (20 respondents). Pedagogies referred to pedagogical practices, strategies, or assignments drawn from common ways of teaching and learning in disciplinary courses GSIs participated in as students. For example, creative writers mentioned implementing workshops and regular freewrites in their courses; literature scholars described highly valuing large group discussions about reading assignments; digital humanists assigned digital texts and multimodal assignments. These pedagogical strategies affected selection of texts and assignments, apart from the disciplinary content of those texts and assignments. For example, some GSIs described how understanding problems with the literary canon led them to choose reading assignments and write assessment language responsive to questions of privilege and diversity. Occasionally, GSIs’ disciplinary backgrounds led to narrowed pedagogical purposes for FYW and narrowed views of first-year students’ academic trajectories. For example, one participant (PhD student in literature) wrote, “I often teach based on what skills students will need to be successful in their literature courses. This is what area I know well, and I feel that I can really give students something to make their college careers more successful.” This participant did not address how these skills would be of use to students who would not go on to take literature courses. These instances demonstrate how imported pedagogies at times resulted in approaches that enriched the FYW classroom and at other times showed GSIs falling back on the familiarity of their own disciplinary knowledge, even if it did not meet student needs.

Skills or expertise (12 respondents). Skills or expertise referred to specific disciplinary-based competencies GSIs felt were assets to them in the classroom. One MA student in literature described expertise in “how to read literature and analyze it to make an interesting argument”; a creative writing MA student named “well-rounded knowledge of different literary works.” Generally, these respondents did not specify how these skills or competencies affected their work as FYW instructors, but others identified specific transferrable skills (such as close reading or primary research skills) that they hoped to pass along to their students. For example, one MA student in creative writing wrote, “I also think that my close reading skill helps me to define analysis to my students. I urge them to analyze everything.” In this category, GSIs felt their personal ability to do the work they expected of their students was an asset they could draw on in teaching. This category suggested some GSIs believed that the literate skills they developed as students were the same literate skills their first-year students needed, or that the ability to read or analyze well formed the basis of expertise needed to teach writing.

Reinforced boundary (7 respondents). Some GSIs made a conscious effort not to import any elements of their home disciplines into the FYW classroom. One MA student in literature wrote, “I do not integrate my literature interests into the writing classroom. I suppose this is because I feel my students signed up for a writing class, not a literature class, and I want to honor that.” Another MA student in literature responded, “I was fortunate enough to receive excellent training from our FYW program that immersed me in the discipline of Rhetoric and Composition and allowed me to get a sense of what is happening in the field. This theory, far more than literary theory, structures my classroom.” Responses in this category reinforced boundaries and suggested a lack of connection or relevance between composition and GSIs’ home disciplines, emphasizing the distinctions between these disciplines and the recognition that writing studies is, indeed, its own discipline. These answers also perhaps signal GSIs’ desire to position themselves as knowledgeable about writing studies and therefore qualified to teach FYW despite pursuing a degree in a field outside of writing studies.

FYW Exports

In this category, participants described how teaching FYW influenced their own writing and research. Specifically, participants’ responses fell into three subcategories: student dispositions and practices, writer and researcher dispositions and practices, and minimal or negative effect. A total of 112 survey respondents answered this open-ended question (all respondents were invited to answer this question).

GSIs’ Dispositions and Practices as Students (7 respondents). Some GSIs described changing their dispositions or practices as students because of their experiences as teachers. For example, they spoke up more in their classes and reached out to their professors more frequently with questions because these were behaviors they wanted their own students to adopt: “I always wish my students were more talkative, so I have become more talkative in my own classes” (MA student in literature). Others managed their time better and became more aware of the pedagogical approaches of their professors and of the institutional structures shaping higher education. GSIs are both students and instructors, and this category seemed to represent how frequent movement between those roles changed how GSIs acted in both roles. Teaching made GSIs more aware of how student behaviors were perceived by instructors and vice versa.

GSIs’ Dispositions and Practices as Writers and Researchers (83 respondents). Many GSIs felt that teaching FYW influenced their dispositions and practices as writers and researchers. While some GSIs wrote generally about this influence, most responses fell into three subcategories: GSIs described how teaching FYW 1) improved their skills or practices as writers and researchers, 2) prompted reflection, and 3) inspired research projects and topics. In a few instances, participants’ longer responses fell into more than one of the subcategories below.

Participants described how teaching improved their skills or practices (33 respondents) as writers, including helping them write clearer prose, use correct grammar and punctuation, engage in more extensive revision, employ more strategic library research practices, manage time better, and so on. One PhD student in literature said, “I’ve revised my writing style immensely [ ... ] and my writing and research processes have dramatically altered and become much more productive and generative.” Participants described how teaching introduced them to new writing strategies (like “shitty first drafts” or new ways to structure an argument) or reminded them of effective practices learned previously (like drafting early and proofreading carefully). These GSIs tried to avoid hypocrisy and “practice what they preached” (PhD student in literature). If they required their students to create outlines, they felt they needed to do the same. Others felt teaching a particular principle helped them learn that principle better or motivated them to work harder at their own writing. One PhD student in rhetoric and composition described becoming “much more diligent in my search for personal improvement.”

In responses about how teaching prompted reflection (24 respondents), participants said they generally became more aware of their own writing processes or reformulated the way they understood writing. One participant (PhD student in rhetoric and composition) said, “Studying RC [rhetoric and composition] has allowed me to reflect and understand my own moves as a writer and that metacognition has given me more confidence.” Another (PhD student in creative writing) shared that teaching had a “huge impact on what I consider ‘canonical texts’ and my thinking about what we mean by ‘good writing,’ in general.” Others described a recursive process where teaching prompted them to reflect on and better understand their writing practices so they could use that understanding to teach their students.

Finally, 24 respondents described how teaching FYW inspired the content of their research. For example, one participant (MA student in rhetoric and composition) shared, “My graduate studies are about teaching at the community college level, so it has impacted that a lot obviously.” Generally, respondents who credited FYW with inspiring research projects were graduate students in rhetoric and composition, but one literature PhD student described how teaching “definitely fuels my own interests: I think a lot about the ways in which people taught and learned in the Renaissance and how reading, writing, and teaching practices have changed over time.”

Minimal, None, or Negative Effect (18 respondents). Some participants shared that teaching FYW had minimal or no impact on their writing and research practices. An MFA student in creative writing wrote, “Writing papers has always come easy to me and teaching writing hasn’t changed that in anyway,” while a PhD student in literature wrote, “Teaching comp hasn’t had a strong impact on my writing because the difficulties of graduate level research and writing are very different from the challenges my students face.” (There are echoes here of the GSIs in Dylan Dryer’s research, who saw themselves as having more agency and complexity as writers than their undergraduate students.) Other survey responses showed GSIs felt their graduate work impacted their teaching but not the other way around: “Teaching writing hasn’t yet impacted my own studies but my studies have certainly affected my teaching” (MFA student in creative writing). Such comments suggest GSIs may be more comfortable importing familiar content from their home disciplines into FYW than exporting and absorbing unfamiliar writing studies concepts. A few participants described how teaching FYW negatively affected their graduate work, as when FYW students’ “less developed” (MA student in technical/professional communication) and “amateurish” (PhD student in literature) writing “infected” (MA student in literature) their own writing, or when teaching “created a time vacuum” (MFA student in creative writing) drawing them away from their own research or writing.

Responses in this category did not always reflect a negative attitude towards teaching itself. An MFA student in creative writing shared, “I generally feel that my creative writing projects are extremely separate from teaching English 101. ... I really love teaching so far, but I can’t let it overwhelm my schedule to the point that I don’t write.” Even when GSIs enjoy teaching, they may see it as an active, time-sucking obstacle to their success as students. This is likely especially true for GSIs studying in one discipline and teaching in another, constrained as they are by limited time to do both. Like the “reinforced boundary” category under “Disciplinary Imports” above, participants here seemed to feel that the quality of their work as researchers and writers depended on separating their scholarly work from their teaching. GSIs in Jessica Restaino’s study similarly felt they had an “either/or” choice between being a student and being a teacher (115). Balancing teaching with other scholarly pursuits is a struggle for all academics, but it may be of particular concern among GSIs who are students first, teachers second.

Navigating Disciplinarity: Interview Data

Ken Hyland writes that individuals “bring different experiences, inclinations and proclivities to their performances as academics, teachers, and students. Disciplinary membership, and identity itself, is a tension between conformity and individuality, between belonging on the one hand and individual recognition on the other” (26). In light of Hyland’s emphasis on the communal elements of disciplinarity, inviting new GSIs to engage with writing studies as a discipline means more than simply presenting them with the content of writing studies. It also means helping them navigate their identities and the relationship of those identities to larger disciplinary and programmatic goals and philosophies. Donna Qualley argues, “Much of the work involved in developing and deepening one’s expertise as a GSI in the first-year writing program seems to involve learning to notice what the larger discipline and the local community deem important about student writing” (88). The challenge for GSIs is that they are still learning what the larger discipline deems important and negotiating that new knowledge with what their personal experiences and home disciplines have taught them about writing—all while being expected to teach writing competently.

Follow-up interviews with GSIs in this study showed they recognized writing studies as an established discipline, and this recognition affected whether they saw themselves as having the authority and expertise to teach the course. For example, Ray, an MFA student in creative writing, felt his lack of background in writing studies made him less qualified to teach FYW: “I’m making the most of it and really enjoying it and having a good time, but nonetheless, it’s not like my area of expertise necessarily. Or it’s not something that I’ve devoted years previously to practicing.” Ray’s comment suggests his awareness that writing studies is an area of expertise for others and that one could spend years developing that expertise. Other GSIs showed a similar awareness of writing studies’ disciplinary status when they talked about feeling qualified, or not, to teach. Sarah felt less qualified to teach FYW because she did not “actually have any rhetorical training like the people in rhet/comp do.” She felt her partner, a GSI who did study rhetoric, had “expertise that I just don’t have” and so was able “to do a lot more with [her] students.” This suggests that GSI resistance to their formal preparation may be based less in a dismissive attitude towards writing studies and more in concerns about lacking expertise in a discipline that GSIs recognize as having depth and breadth they have not mastered.

In their study of first-year writers, Reiff and Bawarshi identified what they call “boundary guarders”: writers who relied on “well-worn paths—routinized inclinations and default uptakes on genres” (331). These writers abstracted less and tended to draw on, or I might say import, whole prior genres rather than discrete writing strategies as they tackled new writing tasks. Similarly, GSIs who lacked expertise in writing studies imported whole ways of writing and teaching from their home disciplines or their own experiences as students rather than reflectively importing and adapting smaller, discrete strategies. We might call these GSIs who import heavily “boundary-guarders.” For example, Emma, a literature PhD student, shared that she did not feel qualified to teach FYW because she was “a literature person” not “a comp/rhet person.” She struggled with her graduate composition theory course because it focused on “big picture stuff ... which is good, but it’s kind of a lot to hit you with when you’re trying to even figure out how to be a teacher.” To manage this difficulty, Emma imported content and pedagogies that built on her own strengths: she restructured her FYW course as a film class in which students wrote about films, practiced frequent revision, and received personal and frequent feedback. Although she felt some in her department did not support this choice, she said, “Obviously, I have pedagogical reasons for it. It’s not like I’m lazy ... it’s that I think these things are actually really useful.” Emma felt her approach was useful because of her prior experience as a student who had benefited from intense individualized feedback on her own writing about film. Although some might look at Emma’s film-based course design and consider her “resistant” to writing studies, Emma’s real struggle seemed to be how to “learn a whole new thing while I’m trying to teach it and be a student as well,” an experience she found “really intimidating and bad.” Again, we see here the challenge of the teaching “time vacuum” identified above. Importing her prior disciplinary expertise, without significant adaptation, seemed to Emma to be best option for managing this intimidating situation. Her course was grounded in the familiar-to-her genre of literary textual analysis, but her practice of encouraging frequent revision and providing frequent feedback would find support in writing studies. Emma cared about her students and their progress, but felt she might have had a better experience if she had first worked in a classroom with a mentor. Emma’s concerns reinforce Jennifer Grouling’s argument that GSI resistance is often part of a larger resistance to the pressures of graduate school rather than to teaching or writing studies specifically.

Although the other GSIs I interviewed seemed less likely to strike out as independently as Emma did, Emma’s focus on providing her students with something “useful” was reflective of other interviewees: all of them wanted to provide valuable learning experiences for their students, even when they felt they lacked the expertise to do so. This concern for teaching students well was also apparent in the GSIs in Brewer’s and Restaino’s studies, suggesting this is a common concern for many GSIs. In service of this goal of helping students, when GSIs either lacked a full understanding of composition theory or disagreed with composition theory, they tended to rely on their own proto-theories and experiences of “what works.” For example, Charles (MFA student in creative writing) appreciated what he learned in his composition practicum about grammar instruction, but also felt he was “more of a current-traditionalist than is popular at the moment.” In part this was because he had experienced “a very current-traditionalist education and [saw] the benefits of it.” Although Charles appreciated writing studies’ critiques of certain kinds of grammar instruction (he avoided “drill and kill” methods), he spent more time on grammar instruction than his program emphasized because of his prior experiences as a student who benefitted from explicit grammar instruction.

In contrast to “boundary guarders,” Reiff and Bawarshi described how some first-year writers became boundary crossers who, recognizing their status as novices, “reported more willingness to shift away from the writing experiences with which they felt comfortable, confident, and successful” (330). Similarly, GSIs who were more familiar with writing studies felt more qualified but also were more willing to accept new ideas and to acknowledge gaps in their knowledge. Essentially, they recognized when importing prior experience and knowledge would not be enough; they were open to the “exports” writing studies offered: new knowledge that could influence their practices as teachers and as students. Diana, a PhD student in literature who had taken extra coursework in composition and worked as a writing tutor, said, “I think the fact that I did take all of the graduate coursework and that I also entered my program already interested in rhetoric and composition makes me feel more qualified than just like a typical PhD student who has to teach it because it’s part of their funding package.” But she also seemed more aware of and comfortable with what she still did not know about writing: “I try to make it clear to my students that I’m not some expert on writing... . I definitely emphasize to them that I’m not qualified to teach the specific genres of writing that they will probably encounter in their own majors, ... which is partly why I like the writing-about-writing philosophy too.” Diana’s awareness of what she did not know about writing (specific academic genres) illustrates her understanding of key concepts in writing studies: genre, audience, rhetorical situation. Her deeper understanding of writing studies made her more comfortable acknowledging to her students areas in which she lacked expertise and more able to provide them with metaknowledge that would help them when they encountered unfamiliar genres.

Gabrielle, an MA student in rhetoric and composition, also described recognizing what she did and did not know about writing. When her students in a writing-in-the-disciplines-focused FYW course struggled to understand the scientific writing they were reading, Gabrielle initially felt unqualified to respond until she remembered that “it all comes back to rhetoric, it all comes back to understanding an audience.” Her newfound knowledge of fundamental rhetorical concepts helped her regain her bearings, and she then thought, “Okay, I got this.” Focusing on and understanding their own metaknowledge about writing (about genre, rhetorical situation, audience, and so on) enabled both Diana and Gabrielle to feel comfortable teaching students about unfamiliar genres in contrast to GSIs who simply imported genres and strategies that worked for them as students.

As mentioned above, sometimes the barriers to applying formal WPE had nothing to do with resistance and everything to do with time. Andy, for example, said he had “learned a hell of a lot of groovy shit” that he wanted to apply to his teaching, but he didn’t “have the time or the energy to spare to work and massage my pedagogy” because of his dissertation. Andy was even reminded by his WPA that graduate students must balance time spent on teaching with other priorities of graduate work. Perhaps as a result of time constraints, GSIs often prioritized their personal, idiosyncratic goals for student learning, goals that sometimes reflected programmatic outcomes and sometimes did not. GSIs with interest in expanding their disciplinary knowledge in writing studies felt constrained by their limited time as busy graduate students. Because they recognized their deficiencies as subject-matter experts, but had to teach FYW anyway, they needed to attach to some locus of expertise. To survive, they depended on their own experiences as writers and as students in their home disciplines to fill gaps in their expertise, making them less likely to export or apply the “groovy” new knowledge that writing studies offered them.

Discussion

What Should a Writing Teacher Know and How Can They Know It?

Drawing on the work of Andrew Abbott, Wardle and Downs explain that disciplinary boundaries “specify not what one is allowed to read, but the bare minimum one must read for disciplinary participation.” A “shared set of ‘must-reads’ seems necessary to the formation of a community of practice,” but this “canon” is dynamic and non-limiting (“Understanding the Nature of Disciplinarity” 115). As noted above, many GSIs did not find reading in the field particularly helpful to their work as teachers. If there is a bare minimum one must read for disciplinary participation, GSIs may struggle to the see the value in their reading until they reach that minimum and begin to understand larger disciplinary conversations. Readings may also become more relevant over time as they recognize how practical classroom concerns connect to disciplinary inquiry and theorizing; GSIs in this study seemed to value readings more when they had more teaching experience. The concept of what one must read also raises questions about what constitutes the key readings and knowledge of our field, questions that do not and should not have simple answers. What is the bare minimum that a writing teacher must know to participate in the discipline by teaching it?

Our field’s professional organizations have defined what principles lead to effective writing instruction. As Hansen has written, the Statement of Principles for the Postsecondary Teaching of Writing implicitly outlines “eight knowledge areas that teachers should command,” including 1) knowledge about “the rhetorical tradition, the canons of rhetoric, and how to teach students to analyze and respond to new rhetorical situations,” 2) “what is involved in analyzing and addressing audiences,” (4) “theories and practices of composing,” 4) genre theory, 5) “different writing processes” and “how to analyze and teach them,” 6) “formative and summative evaluation” including how to “create and use grading criteria and rubrics,” 7) “theories and practices of using electronic media to produce effective rhetoric” and the ability to “teach students to do the same,” 8) “how thinking and writing vary by discipline” and how to help students transfer knowledge and practice to other courses (149). I would add that effective teachers should also be familiar with antiracist pedagogies, disability studies, students’ right to their own language, and other pressing areas for ensuring a just and accessible classroom for undergraduate students. GSIs must master not only declarative knowledge about the theories and research of the field but also pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman), which includes everything from transmitting content clearly to knowing “what makes the learning of specific topics easy or difficult: the conceptions and preconceptions that students of different ages and backgrounds bring with them” (9). Essentially, GSIs must become familiar with what Michael Carter calls “ways of doing, knowing, and writing” (403) and teaching in a discipline. If GSIs come from a traditional English or humanities major characterized by analyzing and composing research from sources, for example, they may be jarred by writing studies’ focus on textual production and rhetorical performance. It is a lot to cover.

E. Shelley Reid has questioned what actually can be “covered” in the limited time available to prepare GSIs and suggests “uncoverage” as an alternative—an approach that positions WPE “as an intellectual engagement rather than an inoculation, as practice in a way of encountering the world rather than mastery of skills or facts, as preparation for a lifetime of thinking like a teacher” (Uncoverage). Learning to think like a writing teacher may happen more easily when we introduce GSIs to the values of writing studies as a sort of frame for understanding the foundational texts and debates of writing studies. Wardle and Downs have articulated some of writing studies’ values: “inclusion, access, respecting difference, facilitating interaction, emphasizing localism, valuing diverse voices, and empowering writers to engage in textual production” (Understanding the Nature of Disciplinarity 130). Whether and how new teachers enact these values in their classrooms carries important consequences for the writing instruction offered to undergraduates. Some of these values may intersect with or contradict GSIs’ prior experiences and disciplinary training.

Consider the values of inclusion, access, difference, and valuing diverse voices. Asao B. Inoue has explained how white language supremacy has shaped our discipline and what values and structures we accept as natural (2019; Friday), and what we convey to new writing teachers as natural. Carmen Kynard has also witnessed how “disciplinary whiteness” exists on our campuses and in our scholarly publications (Teaching While Black; Vernacular Insurrections). Writing pedagogy educators must help GSIs recognize how the “disciplining” nature of academic fields is bound up with questions of race, access, and power, questions that influence their practices as teachers and their students’ experiences as learners. This study has looked specifically at how GSIs’ disciplinary identities shape their teaching, but similar questions might also be asked about how GSIs’ race, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, religion, immigration status, socioeconomic status, neurodiversity, and ability influence how they teach writing, what disciplinary values they enact, and how a diverse student population receives their instruction. More research is needed in response to these questions.

When writing teachers are equipped with a sense of the values and central knowledge of the field (including critiques of our field’s history and practices informed by concerns of social justice), they will better be able to reflexively judge the imports they hope to bring into the FYW classroom. They will be better prepared to think like teachers, as Reid urges (Uncoverage). Charles (MFA student in creative writing) demonstrated this reflexivity in the context of examining disciplinary values from his home discipline and the discipline of writing studies. For his final project in his composition theory course, Charles chose to investigate the connections and divergences between composition pedagogy and creative writing pedagogy. Both pedagogies value writing process and production, but Charles found that creative writing was more likely to value the “lone genius” narrative. In this sense, creative writing may uphold some gatekeeping that writing studies would reject. Charles felt creative writing could learn from the more inclusive and access-oriented perspective of writing studies. Charles’ chosen project allowed him to consciously consider disciplinary intersections and to find “exports” he wanted to bring back to creative writing, but many GSIs do not engage in this kind of disciplinary reflection because their formal preparation does not explicitly ask for it.

From Student to Practicing Teacher

Robertson, Taczak, and Yancey argue that new first-year writing students struggle adjusting to college writing because they are moving from a curriculum based primarily in reading imaginative texts that express an author’s artistic vision to a curriculum based primarily in writing nonfiction texts that inform and communicate with an audience. Their absence of prior knowledge in college genres leaves them confused about how to respond to what college-level writing asks of them. A similar problem may be occurring with our GSIs, many of whom have never taken a course in writing studies (not even FYW) before teaching in a writing-focused curriculum and many of whom have been trained in analysis of texts more than in production of texts. Grouling also points out that GSIs may struggle to integrate what they learn in their composition theory courses because they approach those courses as students: they attempt to learn the content and regurgitate right answers. And, indeed, they are typically positioned as students earning grades in their composition practicums. WPE places GSIs in the complex middle position of being both a student and a teacher and must allow them room and flexibility for both roles (Restaino). In preparing GSIs to think like teachers, we want them to “investigate their previous theories, compare those to concepts in the field, and develop their own new theories of teaching composition” (Grouling). Applying and constructing theory as a teacher may be discomfiting to GSIs who are more comfortable learning theories as students, but WPE should engage GSIs in the discomfort in order to prepare them to manage imports and exports across their growing disciplinary knowledge and identities.

As GSIs struggle to form teacherly identities and authority, many draw on prior experience to help them feel qualified (as seen in Emma’s example). If WPE can help GSIs develop metaknowledge about writing, this may position GSIs well to help themselves and their students manage disciplinary imports and exports (as in the examples of Diana and Gabrielle). Misty Anne Winzenried, in her study of GSIs teaching writing across the disciplines, found that GSIs with educational emphases outside of English studies were able to “mediate the tensions between general academic and discipline-specific writing” for students because certain knowledge had “not yet become entrenched or tacit” for them. Although Winzenried’s study focused on GSIs working outside of English departments, her work carries implications for FYW GSIs with emphases in literature, creative writing, and other areas. Perhaps diverse disciplinary backgrounds can allow them to “mediate” disciplinary tensions.

On the other hand, Driscoll found that some GSIs “are unaware of writing and communicative practices in diverse disciplines and accept GWSI [General Academic Writing Skills Instruction] without question” (73). Similarly, Wardle found that FYW teachers tasked with teaching writing-in-the-disciplines “did not have a clear picture of what academic writing might be, so they saw their own genres [from their home disciplines, typically English] as the norm” (Can Cross-Disciplinary Links 13). These teachers’ lack of genre awareness across disciplines limited their ability to achieve program outcomes like preparing students in various majors outside the humanities for writing across four years of college. GSIs in my study experienced a similar struggle, sometimes structuring their classes around imports of their own expertise by teaching students to write interpretive analysis papers—a genre that may not prepare engineering students, for example, for future writing in their discipline. In writing studies, we must help GSIs use their disciplinary backgrounds as assets instead of liabilities in order to best serve undergraduate writing students.

Conclusion: Recommendations for Writing Pedagogy Education

I propose two strategies that can help GSIs make productive use of their prior experiences and knowledge as they move into the role of writing teacher:

-

Reflectively Analyze Imports and Exports. While prior experience, proto-theories, and disciplinary imports can productively and effectively synergize with composition theory and pedagogy, WPE must ask GSIs to carefully and consciously analyze how and to what end they import and export disciplinary knowledge. If teachers’ primary exigence for importing knowledge from their home disciplines is to shore up insecurities about expertise, importing may not result in thoughtful, theorized writing instruction for undergraduates. WPE might “teach for transfer” by asking GSIs to export writing studies concepts like audience, genre, and language to reflectively consider what they know about the values, discourse, and genres of their home disciplines. If GSIs do not consciously recognize what characterizes their discipline’s knowledge and values (perhaps because they see their discipline as the “norm” of academic discourse), writing pedagogy educators might create assignments that encourage students to find and articulate these differences: for example, they could conduct a discourse analysis of a scholarly peer-reviewed work from their home discipline and one from writing studies, identifying differences in values, focus, and ways of knowing. In this way, teacher educators might encourage GSIs to acknowledge, discuss, and write about the disciplinary values and identities they bring with them to FYW and how those values and identities mesh or clash with the foundational knowledge and values of writing studies. This activity could be extended to compare scholarly work from GSIs’ home disciplines with work from the disciplines their FYW students may enter, like biology, engineering, or social work.

-

Engage in Writing Studies as a Disciplinary Community. Paul Prior writes that “disciplinary enculturation” refers “to the continual processes whereby an ambiguous cast of relative newcomers and relative old-timers (re)produce themselves, their practices, and their communities” (xii). GSIs in and beyond the first year of teaching need social spaces to grapple with the theory and research of the field of writing studies: beyond the composition theory course, this might happen in reading groups, conferences, teaching communities, or online spaces. Recent efforts in our field to summarize and stratify our knowledge (including Adler-Kassner and Wardle’s Naming What We Know, Heilker and Vandenberg’s Keywords in Writing Studies, and Ball and Loewe’s Bad Ideas About Writing) articulate central concepts in writing studies in accessible ways that allow new teachers to gain a foundational understanding of the discipline. New teachers might be invited to discuss readings from these texts in cross-tiered teaching groups with instructors who have more expertise. Campuses may also hold mini-conferences where newcomers (GSIs) can articulate and share their newfound knowledge and experiences as writing teachers.

As GSIs teach writing, they are engaging in a social enactment of disciplinary knowledge. By asking GSIs to confront their disciplinary backgrounds, prior experiences, and proto-theories about writing, we invite them into a complex site of learning, transfer, reflection, and becoming in graduate education. We also create space to help GSIs develop the ability to think consciously and reflectively about their disciplinary identities and choices as teachers.

Appendices

Appendix 1: GSI Survey Questions

Questions 1-9 asked participants to identify type of degree pursued, area of study, age, gender, racial/ethnic identity, native language, previous teaching experience, number of semesters taught, and type of training received.

-

Please rate the following to indicate whether/how well they have helped build your confidence as a composition teacher. Use a 1-5 scale, where 1 indicates “didn’t help much at all” and 5 indicates “helped quite a lot.” Use “0” for anything you haven’t encountered yet.

Experience as a writer

Experience as a tutor

Experience as a teacher

Observing other teachers and/or being mentored by other teachers

Role plays, presentations, guest- or practice-teaching

Composition pedagogy/theory course activities or assignments

Reading professional articles

Reflective writing/thinking about teaching

Discussions/exchanges with other peer teachers

Discussions/exchanges with mentors or advisors

Orientation or professional development workshops

Other (please specify)

-

Please rate the following to indicate whether/how well they have helped build your skills as a writing teacher. Use a 1-5 scale, where 1 indicates “didn’t help much at all” and 5 indicates “helped quite a lot.” Use “0” for anything you haven’t encountered yet.

Experience as a writer

Experience as a tutor

Experience as a teacher

Observing other teachers and/or being mentored by other teachers

Role plays, presentations, guest- or practice-teaching

Composition pedagogy/theory course activities or assignments

Reading professional articles

Reflective writing/thinking about teaching

Discussions/exchanges with other peer teachers

Discussions/exchanges with mentors or advisors

Orientation or professional development workshops

Other (please specify)

-

When you face a challenge or a problem as a tutor/teacher, how well do the following help you address that problem? Use a 1-5 scale, where 1 indicates “doesn’t help much at all” and 5 indicates “helps quite a lot.” Use “0” for anything you haven’t encountered or tried yet.

Drawing on my experience as a writer

Drawing on my previous experience as a tutor

Drawing on my previous experience as a teacher

Observing other teachers (or consulting their course materials)

Consulting a mentor or advisor

Remembering strategies from composition pedagogy/theory course activities and assignments

Reading and/or remembering previously read professional articles

Writing/thinking reflectively about teaching

Discussing the issue with other peer teachers

Drawing on orientation or professional development workshops

Other (please specify)

-

What do you see as 3-4 key principles for your teaching of writing? (In other words, what do you think is important for you to do as a writing teacher? What do you try always to do or not do?) (Open Response.)

-

Could you say where those principles come from, or are related to? (Were they from something you read or learned, something you heard of or saw someone doing, some experience you had?) (Open Response.)

-

If your graduate work is in a field outside of rhetoric and composition, what concepts (ideas, theories, scholarly literature, disciplinary practices) from your primary discipline shape the structure and content of the way you teach writing? (Open Response.)

-

What impact, if any, has teaching writing had on your own research and writing practices as a graduate student?

-

How do you plan to use your degree after graduation? What role, if any, do you imagine teaching playing in your career after you complete your degree? (Open Response.)

-

What is the biggest challenge you face in your teaching? (Open Response.)

Appendix 2: GSI Semi-structured Interview Protocol

-

Could you describe your university context (size and type of school, a little about the student population, number of graduate programs and students, etc.)?

-

Could you describe a bit more about your program context? What discipline is your program in, what emphases are available, what is the population of graduate students like (MA and PhD, etc.)?

-

Describe your process for designing your first-year writing course and syllabus. Why did you design the course the way you did? What resources (people, books, websites, graduate coursework notes/lectures, etc.) did you draw on in designing this course?

-

Think of one of the assignments you created for your course this semester. What are the origins of this assignment? What resources (people, books, websites, graduate coursework notes/lectures, etc.) did you draw on in designing this assignment?

-

How do you see your course design carrying out or responding to your first-year writing program’s philosophy and policies?

-

Describe your process for preparing for a typical day in class. What resources (people, books, websites, graduate coursework notes/lectures, etc.) do you rely on to prepare for class?

-

In what ways do you feel most qualified to teach this course, and in what ways do you feel least qualified to teach this course?

-

Describe the central principles or ideas you want your students to take away from your course this semester. Why do you think these principles or ideas are so important?

-

What is the most influential piece of scholarship you’ve read in terms of your own teaching?

-

What connections, if any, do you see between what/how you teach first-year writing and what you are learning in your coursework and research as a graduate student?

-

What are your plans for your career after graduation? What elements of your graduate experience do you feel are best preparing you for your postgraduation plans?

Notes

-

IRB protocol #11862. (Return to text.)

-

The one area where there is a sizable difference between the survey and interview population is in the representation of GSIs studying in a field “other” than literature, rhet/comp, or creative writing. Since a key research question of this study is how disciplinary affiliation affects teaching, out of the 58 survey respondents solicited to participate in follow-up interviews, all participants who indicated they were studying in an “other” field were invited to be interviewed. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth Wardle, editors. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State UP, 2015.

Ball, Cheryl E. and Drew M. Loewe, editors. Bad Ideas About Writing. West Virginia University Libraries Digital Publishing Institute, 2017.

Bastian, Heather. Capturing Individual Uptake: Toward a Disruptive Research Methodology. Composition Forum, vol. 31, 2015. https://compositionforum.com/issue/31/individual-uptake.php.

Berlin, James A. Rhetoric and Reality: Writing Instruction in American Colleges, 1900-1985. Southern Illinois UP, 1987.

Brewer, Meaghan. Conceptions of Literacy: Graduate Instructors and the Teaching of First-Year Composition. Utah State UP, 2020.

---. The Text is the Thing: Graduate Students in Literature and Cultural Conceptions of Literacy. Composition Forum, vol. 42, 2019. https://compositionforum.com/issue/42/text-thing.php.

Carter, Michael. Ways of Knowing, Doing, and Writing in the Disciplines. College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no. 3, Feb. 2007, pp. 385-418.

Crowley, Sharon. Composition in the University: Historical and Polemical Essays. U of Pittsburgh P, 1998.

Dobrin, Sidney I. Introduction: Finding Space for the Composition Practicum. Don’t Call It That: The Composition Practicum, edited by Sidney I. Dobrin, National Council of Teachers of English, 2005, pp. 1-34.

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)envisioning ‘First-Year Composition’ as ‘Introduction to Writing Studies.’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no. 4, Jun. 2007, pp. 552-84.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn. Connected Pedagogy and Transfer of Learning: An Examination of Graduate Instructor Beliefs vs. Practices in First-Year Writing. Journal of Teaching Writing, vol. 28, no. 1, 2013, pp. 53-83.

Dryer, Dylan B. At a Mirror, Darkly: The Imagined Undergraduate Writers of Ten Novice Composition Instructors. College Composition and Communication, vol. 63, no. 3, Feb. 2012, pp. 420-452.

Ebest, Sally Barr. Changing the Way We Teach: Writing and Resistance in the Training of Teaching Assistants. Southern Illinois UP, 2005.

Estrem, Heidi, and E. Shelley Reid. What New Teachers Talk about When They Talk about Teaching. Pedagogy, vol. 12, no. 3, 2012, pp. 449-80.

Gender Distribution of Degrees in English Language and Literature. Humanities Indicators, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 2019. https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/higher-education/gender-distribution-degrees-english-language-and-literature.

Grouling, Jennifer. Resistance and Identity Formation: The Journey of the Graduate Student-Teacher. Composition Forum, vol. 32, Fall 2015. https://compositionforum.com/issue/32/resistance.php.

Hansen, Kristine. Discipline and Profession: Can the Field of Rhetoric and Writing Be Both? Composition, Rhetoric, and Disciplinarity, edited by Rita Malenczyk, et al. Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 134-58.

Heilker, Paul, and Peter Vandenberg, editors. Keywords in Writing Studies. Utah State UP, 2015.

Hesse, Douglas. Teachers as Students, Reflecting Resistance. College Composition and Communication, vol. 44, no. 2, May 1993, pp. 224-31.

Hyland, Ken. Discipline: Proximity and Positioning. The Essential Hyland: Studies in Applied Linguistics. Bloomsbury, 2018.

Inoue, Asao B. 2019 CCCC Chair’s Address: How Do We Language So People Stop Killing Each Other, or What Do We Do about White Language Supremacy. College Composition and Communication, vol. 71, no. 2, Dec. 2019, pp. 352-369.

---. Friday Plenary Address: Racism in Writing Programs and the CWPA. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 40, no. 1, 2016, 134-154.

Kynard, Carmen. Teaching While Black: Witnessing and Countering Disciplinary Whiteness, Racial Violence, and University Race-Management. Literacy in Composition Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-20.

---. Vernacular Insurrections: Race, Black Protest, and the New Century in Composition-Literacies Studies. SUNY P, 2013.

Kytle, Ray. Slaves, Serfs, or Colleagues—Who Shall Teach College Composition? College Composition and Communication, vol. 22, no. 5, Dec. 1971, pp. 339-41.

Latterell, Catherine. The Politics of Teaching Assistant Education in Rhetoric and Composition Studies. PhD diss, Michigan Technological University, 1996.

Marshall, Margaret J. Response to Reform: Composition and the Professionalization of Teaching. Southern Illinois UP, 2004.

Prior, Paul A. Writing/Disciplinarity: A Sociohistoric Account of Literate Activity in the Academy. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1998.

Qualley, Donna. Building a Conceptual Topography of the Transfer Terrain. Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer, edited by Chris M. Anson and Jessie L. Moore. WAC Clearinghouse, 2016, pp. 69-106.

Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Degrees in English Language and Literature. Humanities Indicators, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 2019. https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/higher-education/racialethnic-distribution-degrees-english-language-and.

Rankin, Elizabeth. Seeing Yourself as a Teacher: Conversations with Five New Teachers in a University Writing Program. NCTE, 1994.

Reid, E. Shelley. Preparing Writing Teachers: A Case Study in Constructing a More Connected Future for CCCC and NCTE. College Composition and Communication, vol. 62, no. 4, 2011, pp. 687-703.

---. On Learning to Teach: Letter to a New TA. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 40, no. 2, 2017, pp. 129-45.

---. Uncoverage in Composition Pedagogy. Composition Studies, vol. 32, no. 1, Spring 2004, pp. 15-34.

Reid, E. Shelley, et al. The Effects of Writing Pedagogy Education on Graduate Teaching Assistants’ Approaches to Teaching Composition. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 36, no. 1, Fall/Winter 2012, pp. 32-73.

Reiff, Mary Jo and Anis Bawarshi. Tracing Discursive Resources: How Students Use Prior Genre Knowledge to Negotiate New Writing Contexts in First-Year Composition. Written Communication, vol. 28, no. 3, 2011, pp. 312-37.

Restaino, Jessica. First Semester: Graduate Students, Teaching Writing, and the Challenge of the Middle Ground. Southern Illinois UP, 2012.

Robertson, Liane, et al. Notes toward A Theory of Prior Knowledge and Its Role in College Composers’ Transfer of Knowledge and Practice. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012. https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/prior-knowledge-transfer.php.

Rounsaville, Angela. Selecting Genres for Transfer: The Role of Uptake in Students’ Antecedent Genre Knowledge. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012. https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/selecting-genres-uptake.php.

Schell, Eileen E. Gypsy Academics and Mother-Teachers: Gender, Contingent Labor, and Writing Instruction. Boyton/Cook, 1998.

Serviss, Tricia. The Rise of RAD Research Methods for Writing Studies: Transcontextual Ways Forward. Points of Departure: Rethinking Student Source Use and Writing Studies Research Methods, edited by Tricia Serviss and Sandra Jamieson. Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 3-22.

Serviss, Tricia and Sandra Jamieson. What Do We Mean by Transcontextual RAD Research? Points of Departure: Rethinking Student Source Use and Writing Studies Research Methods, edited by Tricia Serviss and Sandra Jamieson. Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 25-32.

Shulman, Lee S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching, Educational Researcher, vol. 15, no. 2, 1986, pp. 4-14.

Wardle, Elizabeth A. Can Cross-Disciplinary Links Help Us Teach ‘Academic Discourse’ in FYC? Across the Disciplines, vol. 1, 2004. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/articles/wardle2004.pdf.

---. Intractable Writing Program Problems, Kairos, and Writing about Writing: A Profile of the University of Central Florida’s First-Year Composition Program. Composition Forum, vol. 27, 2013. https://compositionforum.com/issue/27/ucf.php.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and Doug Downs. Understanding the Nature of Disciplinarity in Terms of Composition’s Values. Composition, Rhetoric, and Disciplinarity, edited by Rita Malenczyk, et al. Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 111-33.

---. Reflecting Back and Looking Forward: Revisiting Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions Five Years On. Composition Forum, vol. 27, 2013. https://compositionforum.com/issue/27/reflecting-back.php.

Welch, Nancy. Resisting the Faith: Conversion, Resistance, and the Training of Teachers. College English, vol. 55, no. 4, Apr. 1993, pp. 387-401.

Winzenried, Misty Anne. Brokering Disciplinary Writing: TAs and the Teaching of Writing Across the Disciplines. Across the Disciplines, vol. 13, no. 3, Sep. 2016. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/wacta/winzenried2016.pdf.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. Mapping the Turn to Disciplinarity: A Historical Analysis of Composition’s Trajectory and Its Current Moment. Composition, Rhetoric, and Disiciplinarity, edited by Rita Malenczyk, et al., Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 15-35.

Zebrowski, James T. The Political Economy of English: The ‘Capital’ of Literature, Creative Writing, and Composition. Economies of Writing: Revaluations in Rhetoric and Composition, edited by Bruce Horner, et al., Utah State UP, 2017, pp. 68-84.

Importing and Exporting from Composition Forum 45 (Fall 2020)