Composition Forum 26, Fall 2012

http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/

Notes toward A Theory of Prior Knowledge and Its Role in College Composers’ Transfer of Knowledge and Practice

Abstract: In this article we consider the ways in which college writers make use of prior knowledge as they take up new writing tasks. Drawing on two studies of transfer, both connected to a Teaching for Transfer composition curriculum for first-year students, we articulate a theory of prior knowledge and document how the use of prior knowledge can detract from or contribute to efficacy in student writing.

During the last decade, especially, scholars in composition studies have investigated how students “transfer” what they learn in college composition into other academic writing sites. Researchers have focused, for example, on exploring with students how they take up new writing tasks (e.g., McCarthy, Wardle); on theorizing transfer with specific applicability to writing tasks across a college career (e.g., Beaufort); and on developing new curricula to foster such transfer of knowledge and practice (e.g., Dew, Robertson, Taczak). Likewise, scholars have sought to learn what prior knowledge from high school first-year students might draw on, and how, as they begin college composition (e.g. Reiff and Bawarshi). To date, however, no study has actively documented or theorized precisely how students make use of such prior knowledge as they find themselves in new rhetorical situations, that is, on how students draw on and employ what they already know and can do, and whether such knowledge and practice is efficacious in the new situation or not. In this article, we take up this task, within a specific view of transfer as a dynamic activity through which students, like all composers, actively make use of prior knowledge as they respond to new writing tasks. More specifically, we theorize that students actively make use of prior knowledge and practice in three ways: by drawing on both knowledge and practice and employing it in ways almost identical to the ways they have used it in the past; by reworking such knowledge and practice as they address new tasks; and by creating new knowledge and practices for themselves when students encounter what we call a setback or critical incident, which is a failed effort to address a new task that prompts new ways of thinking about how to write and about what writing is.

In this article, then, we begin by locating our definition of transfer in the general literature of cognition; we then consider how students’ use of prior knowledge has been represented in the writing studies literature. Given this context and drawing on two studies, we then articulate our theory of students’ use of prior knowledge, in the process focusing on student accounts to illustrate how they make use of such knowledge as they take up new writing tasks.{1} We then close by raising questions that can inform research on this topic in the future.{2}

Models of Transfer

Early transfer research in the fields of psychology and education (Thorndike, Prather, Detterman) focused on specific situations in which instances of transfer occurred. Conducted in research environments and measuring subjects’ ability to replicate specific behavior from one context to another, results of this research suggested that transfer was merely accidental, but it did not explore transfer in contexts more authentic and complex than those simulated in a laboratory.

In 1992, Perkins and Salomon suggested that researchers should consider the conditions and contexts under which transfer might occur, redefining transfer according to three subsets: near versus far transfer, or how closely related a new situation is to the original; high-road (or mindful) transfer involving knowledge abstracted and applied to another context, versus low-road (or reflexive) transfer involving knowledge triggered by something similar in another context; and positive transfer (performance improvement) versus negative transfer (performance interference) in another context. With consideration of the complexity of transfer and the conditions under which it may or may not occur, Perkins and Salomon suggest deliberately teaching for transfer through hugging (using approximations) and bridging (using abstraction to make connections) as strategies to maximize transfer (7).

In composition studies, several scholars have pursued “the transfer question.” Michael Carter, Nancy Sommers and Laura Saltz, and Linda Bergmann and Janet Zepernick, for example, have theorized that students develop toward expertise, or “write into expertise” (Sommers and Saltz 134), when they understand the context in which the writing is situated and can make the abstractions that connect contexts, as Perkins and Salomon suggest (6). David Russell likewise claims that writing happens within a context, specifically the “activity system” in which the writing is situated, and that when students learn to make connections between contexts, they begin to develop toward expertise in understanding writing within any context, suggesting that transfer requires contextual knowledge (Russell 536). In a later article, Russell joins with Arturo Yañez to study the relationship of genre understanding to transfer, finding, in the case of one student, that students’ prior genre knowledge can be limited to a single instance of the genre rather than situated in a larger activity system; such limited understanding can lead to confusion and subsequent difficulty in writing (n.p.).

Other research has contributed to our understanding of the complexity of transfer as well, notably of the role that motivation and metacognition play in transfer. For instance, Tracy Robinson and Tolar Burton found that students are motivated to improve their writing when they understand that the goal is to transfer what they learn between contexts, an understanding also explored by Susan Jarratt et al. in a study involving interview research with students in upper-division writing courses to determine what might have transferred to those contexts from the first-year composition experience. Results of the research offer three categories from which students accounted for transfer: (1) active transfer, which requires the mindfulness that Perkins and Salomon define as high-road transfer, (2) unreflective practice, in which students cannot articulate why they do what they do, and (3) transfer denial, in which students resist the idea of transfer from first-year composition or don’t see the connection between it and upper-division writing (Jarratt et al. 3). The Jarratt et al. study, perhaps most importantly, suggests that metacognition students develop before transfer occurs can be prompted; students may not necessarily realize that learning has occurred until they are prompted, but this is the point at which transfer can occur (6).

Metacognition as a key to transfer is identified by Anne Beaufort as well: in College Writing and Beyond, Beaufort suggests conceptualizing writing according to five knowledge domains, which together provide a frame within which writers can organize the context-specific knowledge they need to write successfully in new situations. These domains—writing process knowledge, rhetorical knowledge, genre knowledge, discourse community knowledge, and content knowledge—provide an analytical framework authors can draw on as they move from one context to another. Using this conceptual model, students can learn to write in new contexts more effectively because they understand the inquiry necessary for entering the new context. Beaufort suggests that the expertise students need to write successfully involves “mental schema” they use to organize and apply knowledge about writing in new contexts (17).

More recent scholarship about transfer, including the “writing about writing” approach advocated by Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle, suggests that teaching students about concepts of writing will help foster transfer through a curricular design based on reading and writing as scholarly inquiry such that students develop a rhetorical awareness (553). This writing-as-writing-course-content approach dismisses the long-held misconception that content doesn’t matter, and others are pursuing this same end although with different curricular models (e.g., Sargent and Slomp; Bird; Dew; Robertson; and Taczak).

A little-referenced source of research on transfer that is particularly relevant to this study on how students use prior knowledge in new situations, however, is the National Research Council volume How People Learn: Mind, Brain, Experience, and School. Here transfer “is best viewed as an active, dynamic process rather than a passive end-product of a particular set of learning experiences” (53). As important, according to this generalized theory of transfer, all “new learning involves transfer based on previous learning” (53). All such prior learning is not efficacious, however; according to this theory, prior knowledge can function in one of three ways. First, an individual’s prior knowledge can match the demands of a new task, in which case a composer can draw from and build on that prior knowledge; we might see this use of prior knowledge when a first-year composition student thinks in terms of audience, purpose, and genre when entering a writing situation in another discipline. Second, an individual’s prior knowledge might be a bad match, or at odds with, a new writing situation; in FYC, we might see this when a student defines success in writing as creating a text that is grammatically correct without reference to its rhetorical effectiveness. And third, an individual’s prior knowledge—located in a community context—might be at odds with the requirements of a given writing situation; this writing classroom situation, in part, seems to have motivated the Vander Lei-Kyburz edited collection documenting the difficulty some FYC students experience as a function of their religious beliefs coming into conflict with the goals of higher education. As this brief review suggests, we know that college students call on prior knowledge as they encounter new writing demands; the significant points here are that students actively use their prior knowledge and that some prior knowledge provides help for new writing situations, while other prior knowledge does not.

This interest in how first-year students use prior knowledge in composing, however, has not been taken up by composition scholars until very recently. During the last four years, Mary Jo Reiff and Anis Bawarshi have undertaken this task. Their 2011 article, Tracing Discursive Resources: How Students Use Prior Genre Knowledge to Negotiate New Writing Contexts in First-Year Composition, provides a compilation of this research, which centers on if and how students’ understanding and use of genre facilitates their transition from high school to college writing situations. Conducted at the University of Washington and the University of Tennessee, Reiff and Bawarshi’s study identified two kinds of students entering first year comp: first, what they call boundary crossers, “those students who were more likely to question their genre knowledge and to break this knowledge down into useful strategies and repurpose it”; and second, boundary guarders, “those students who were more likely to draw on whole genres with certainty, regardless of task” (314). In creating these student prototypes, the researchers drew on document-based interviews focused on students’ use of genre knowledge early in the term, first as they composed a “preliminary” essay and second, as they completed the first assignment of the term:

Specifically, we asked students to report on what they thought each writing task was asking them to do and then to report on what prior genres they were reminded of and drew on for each task. As students had their papers in front of them, we were able to point to various rhetorical conventions and ask about how they learned to use those conventions or why they made the choices that they made, enabling connections between discursive patterns and prior knowledge of genres. (319)

Based on this study, Reiff and Bawarshi identify two kinds of boundary-guarding students, and key to their definition is the use of what they call “not talk”:

The first, what might be called “strict” boundary guarding, includes students who report no “not” talk (in terms of genres or strategies) and who seem to maintain known genres regardless of task. The second kind of boundary guarding is less strict in that students report some strategy-related “not” talk and some modification of known genres by way of adding strategies to known genres. (329)

These students, in other words, work to maintain the boundary marking their prior knowledge, and at the most add only strategies to the schema they seek to preserve. By way of contrast, the boundary crossing student accepts noviceship, often as a consequence of struggling to meet the demands of a new writing task. Therefore, this writer seems to experience multiple kinds of flux—such as uncertainty about task, descriptions of writing according to what genre it is not, and the breakdown and repurposing of whole genres that may be useful to students entering new contexts in FYC (329).

What’s interesting here, of course, isn’t only the prototypes, but how those prototypes might change given other contexts. For example, what happens to students as they continue learning in the first term of FYC? What happens when students move on to a second term and take up writing tasks outside of first-year composition? Likewise, what difference might both curriculum and pedagogy make? In other words, what might we do to motivate those students exhibiting a boundary-guarding approach to take up a boundary-crossing one? And once students have boundary-crossed, what happens then? How can we support boundary-crossers and help them become more confident and competent composers?{3}

Where Many Students Begin: Absent Prior Knowledge

As documented above, it’s a truism that students draw on prior knowledge when facing new tasks, and when that acquired knowledge doesn’t fit the new situation, successful transfer is less likely to occur; this is so in writing generally, but it’s especially so as students enter first-year composition classrooms in college. At the same time, whether students are guarding or crossing, they share a common high school background. Moreover, what this seems to mean for virtually all first-year college composition students, as the research literature documents but as we also learned from our students, is that as students enter college writing classes, there’s not only prior knowledge, but also an absence of prior knowledge, and in two important areas: (1) key writing concepts and (2) non-fiction texts that serve as models. In part, that’s because the “writing” curricula at the two sites—high school and college––don’t align well. As Arthur Applebee and Judith Langer’s continuing research on the high school English/Language Arts curriculum shows, the high school classroom is a literature classroom, whereas the first-year writing classroom—which despite the diverse forms it takes, from first-year seminars to WAC-based approaches to cultural studies and critical pedagogy approaches (see Fulkerson; Delivering College Composition)—is a writing classroom. The result for our students—and, we think, others like them––is that they enter college with very limited experience with the conceptions and kinds of writing and reading they will engage with during the first year of postsecondary education.

In terms of how such an absence might occur, the Applebee and Langer research is instructive, especially in its highlighting of two dimensions of writing in high school that are particularly relevant in terms of absent prior knowledge. First is the emphasis that writing receives, or not, in high school classrooms; their studies demonstrate an emphasis placed on literature with deleterious effects for writing instruction:

In the English classes observed, 6.3% of time was focused on the teaching of explicit writing strategies, 5.5% on the study of models, and 4.2% on evaluating writing, including discussion of rubrics or standards. (Since multiple things were often going on at once, summing these percentages would overestimate the time devoted to writing instruction.) To put the numbers in perspective, in a 50-minute period, students would have on average just over three minutes of instruction related to explicit writing strategies, or a total of 2 hours and 22 minutes in a nine-week grading period. (“A Snapshot” 21)

Second, and as important, is the way that writing is positioned in the high school classes Applebee and Langer have studied: chiefly as preparation for test-taking, with the single purpose of passing a test, and the single audience of Britton’s “teacher-as-examiner.” Moreover, this conclusion echoes the results of the University of Washington Study of Undergraduate Learning (SOUL) on entering college writers, which was designed to identify the gaps between high school and college that presented obstacles to students. Their findings suggest that the major gaps are in math and writing, and that in the latter area, writing tests themselves limit students’ understanding of and practice in writing. As a result, writing’s purposes are truncated and its potential to serve learning is undeveloped. As Applebee and Langer remark, “Given the constraints imposed by high-stakes tests, writing as a way to study, learn, and go beyond—as a way to construct knowledge or generate new networks of understandings . . . is rare” (26). One absence of prior knowledge demonstrated in the scholarship on the transition from high school to college is thus a conception and practice of writing for authentic purposes and genuine audiences.

Writers are readers as well, of course. In high school, the reading is largely (if not exclusively) of imaginative literature, whereas in college, it’s largely (though not exclusively) non-fiction, and for evidence of impact of such a curriculum, we turn to our students. What we learned from them, through questionnaires and interviews, is that their prior knowledge about texts, at least in terms of what they choose to read and in terms of how such texts represent good writing, is located in the context of imaginative literature, which makes sense given the school curriculum. When asked “What type of authors represent your definition of good writing?” these students replied with a list of imaginative writers. Some cited writers known for publishing popular page-turners––Michael Crichton, James Patterson, and Dan Brown, for instance; others pointed to writers of the moment––Jodi Picoult and Stephenie Meyer; and still others called on books that are likely to be children’s classics for some time to come: Harry Potter, said one student, “is all right.” Two other authors were mentioned—Frey, whose A Million Little Pieces, famously, was either fiction or non-fiction given its claim to truth (or not); and textbook author Ann Raimes. In sum, we have a set of novels, one “memoir,” and one writing textbook—none of which resembles the non-fiction reading characteristic of first-year composition and college more generally. Given the students’ reading selections, what we seem to be mapping here, based on their interviews, is a second absence of prior knowledge.

Of course, the number of students is small, their selections limited. These data don’t prove that even these students, much less others, have no prior knowledge about non-fiction. But the facts (1) that the curricula of high schools are focused on imaginative literature and (2) that none of the students pointed to even a single non-fiction book—other than the single textbook, which identification may itself be part of the problem––suggest that these may not have models of non-fiction to draw on when writing their own non-fiction. Put another way, when these students write the non-fiction texts characteristic of the first-year composition classroom, they have neither pre-college experience with the reading of non-fiction texts nor mental models of non-fiction texts, which together constitute a second absence of prior knowledge.

Perhaps not surprisingly, what at least some students do in this situation is draw on and generalize their experience with imaginative texts in ways that are at odds with what college composition instructors expect, particularly when it comes to concepts of writing.{4} When we asked students how they wrote and how they defined writing, for example, we saw a set of contradictions. On the one hand, students reported writing in various genres, especially outside of school. Moreover, unlike the teenagers in the well-known Pew study investigating teenagers’ writing habits and understandings––for whom writing inside school is writing and writing outside school is not writing but communication––the students we interviewed do understand writing both inside and outside school as writing. More specifically, all but one of the students identified writing outside school as a place where they “use writing most,” for example, with all but one identifying three specific practices––taking notes, texting, and emailing––as frequent (i.e., daily) writing practices. In addition, two writers spoke to particularly robust writing lives; one of them noted, for instance, writing

[i]nside school. Taking notes. Inside the classroom doing notes. If not its writing assignments. Had blog for a while; blog about everyday life [she and three friends]; high school sophomore through senior year; fizzled out b/c of life; emails; hand written letters to family members.

A second one described a similar kind of writing life, his located particularly in the arts: “Probably [it would] be texting . . . the most that I write. I also write a little poetry; I’m in a band so I like to write it so that it fits to music; a pop alternative; I play the piano, synth and sing.”

On the other hand, given that many of these texts—emails and texts, for example—are composed to specific audiences and thus seem in that sense to be highly rhetorical, it was likewise surprising that every one of the students, when asked to define writing, used a single word: expression. One student thus defined writing as a “way to express ideas and feelings and to organize my thoughts,” while another summarized the common student response: “I believe writing is, um, a way of expressing your thoughts, uh, through, uh, text.” In spite of their own experience as writers to others, these students see writing principally as a vehicle for authorial expression, not as a vehicle for dialogue with a reader or an opportunity to make knowledge, both of which are common conceptions in college writing environments. We speculate that this way of seeing writing—universally as a means of expression in different historical and intellectual contexts—may be influenced by the emphasis on imaginative authorship in the high school literature curriculum, in which students read poets’, novelists’, and dramatists’ writing as forms of expression. Likewise, the emphasis on reading in high school, at the expense of writing, means that it’s likely that reading exerts a disproportionate influence on how these students understand writing itself, especially since the writing tasks, often a form of literary analysis, are also oriented to literature and literary authorship. And more generally, what we see here—through these students’ high school curricula, their own reading practices, and their writing practices both in but mostly out of school––is reading culture-as-prior-experience, an experience located in pre-college reading and some writing practices, but one missing the conceptions, models, and practices of writing as well as practices of reading that could be helpful in a new postsecondary environment emphasizing a rhetorical view of both reading and writing. Or: absent prior knowledge.

A Typology of Prior Knowledge, Type One: Assemblage

While we speculate that college students, like our students, enter college with an absence of prior knowledge relevant to the new situation, how students take up the new knowledge relative to the old varies; and here, based on interview data, writing assignments, and responses to the assignments, we describe three models of uptake. Some students, like Eugene, seem to take up new knowledge in a way we call assemblage: by grafting isolated bits of new knowledge onto a continuing schema of old knowledge. Some, like Alice, take up new knowledge in ways we call remix: by integrating the new knowledge into the schema of the old. And some, like Rick, encounter what we call a critical incident—a failure to meet a new task successfully—and use that occasion as a prompt to re-think writing altogether.

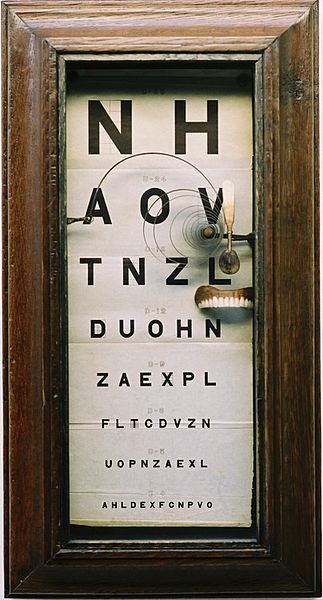

Eugene, who seems to be an example of Reiff and Bawarshi’s border guarders, believes that what he is learning in FYC is very similar to what he learned in high school. How he makes use of prior knowledge and practice about writing is what we call assemblage: such students maintain the concept of writing they brought into college with them, breaking the new learning into bits, atomistically, and grafting those isolated “bits” of learning onto the prior structure without either recognition of differences between prior and current writing conceptions and tasks, or synthesis of them. Such bits may take one or both of two forms: key terms and strategies. Taken together, the conception of writing that students develop through an assemblage model of prior knowledge is very like the assemblage “Vorwarts!” in its remaking of the earlier structure of the eye chart: the new bits are added to it, but are not integrated into it but rather on top of it, such that the basic chart isn’t significantly changed at all.

When Eugene, a successful AP student in high school whose score enabled him to exempt the first of the two first-year composition courses at Florida State, entered English 1102, the second-term, research and argument course, he articulated a dualistic view of writing—for writing to be successful, “you have the right rhetoric and the right person in the right manner,” he observed—and believed that writing operates inside a transmission model through which his writing would allow him “to get his message across.” Interestingly, he believed that he was “really prepared for college”: “[in high school] we were doing a lot of papers that talked about literary devices so I basically knew a lot of literacy devices so there wasn’t a lot more to learn necessarily, I guess more fine-tuning of what I had already learned.” And what there was to learn, Eugene didn’t find worthwhile, in part because it fell outside what he did know: “I don’t like research papers because I don’t know how they work very well and collecting sources and analyzing.” He noted that he was better at “evaluating an article and finding a deeper meaning,” which is the purpose, of course, of the literary analysis texts he wrote in high school.

As he begins his college writing career, then, Eugene establishes a three-part pattern that continues throughout English 1102 and the next term: (1) he confuses and conflates the literary terms of high school and the literacy and rhetorical terms and practices of college; (2) he continues to believe that “there wasn’t a lot more to learn”; and (3) he relies on his prior knowledge of writing, one located chiefly in the role of the unconscious in writing process. As he analyzes his progress in terms of writing, for example, he notes the central role of the unconscious:

my main point is that writing is unconsciously understanding that certain genres that have certain formalities where I have progressed and so where I have progressed is I can put names and places to genres; writing is pretty much unconscious how you are adjusting the person you are talking to and how you are writing.

In this case, the unconscious element of writing provides the central element of Eugene’s concept of writing, and as English 1102 continues and in the semester that follows, Eugene struggles to find terms that he can comfortably graft onto that central understanding.

During the course of two semesters, Eugene was interviewed four times, each time nominating his key terms for composing, and in this data set, we can also see Eugene struggling to make his prior conception of writing work with the new conception of writing to which he is being introduced. In all, he nominated 18 terms: audience and genre were both mentioned three times (once each in three of the four interviews), with other terms each suggested once: reflection, tone, purpose, theme, exigence, diction, theory of writing, imagination, creativity, and rhetorical situation. Some of the terms—rhetorical situation and exigence, for instance—came from his first-year composition class, while others—diction and imagination—were terms located in his high school curriculum. As he continued into the semester following English 1102, Eugene held on to genre, saying in one interview immediately following English 1102 that “I still have to go with genre [as] important and everything else is subcategories,” in the next that genre was still important but not something he needed to think about, as he worked “unconsciously”:

A lot of my writing is like unconsciously done because it’s been ingrained in me to how writing is done. Even though I probably think of genre I don’t really think of it. Writing just kind of happens for me.

And in the final interview, Eugene retrospectively notes that what he gained was a “greater appreciation” of genre, “for the role genre plays in writing. [I]t went from being another aspect of writing to the most important part of writing as a result of ENC 1102.” Genre for Eugene, then, seems to be mapped assemblage-like onto a fundamental and unchanging concept of writing located in expression and the unconscious.

In the midst of trying to respond to new tasks like the research project and unable to frame them anew, Eugene defaults to two strategies that he found particularly helpful. One of these was multiple drafting, not to create a stronger draft so much, however, as to have the work scaffolded according to goals: “Most useful was the multiple drafts, being able to have smaller goals to work up to the bigger goal made it easier to manage.” The second strategy Eugene adopted both for English 1102 and for writing tasks the next semester was “reverse outlining,” a practice in which (as its name suggests) students outline a text once it’s in draft form to see if and how the focus is carried through the text. This Eugene found particularly helpful: “something new I hadn’t experienced before was the reverse outline because it helped me to realize that my paragraphs do have main points and it helps me realize where I need main points.” Interestingly, the parts-is-parts approach to writing Eugene values in the smaller goals leading to larger ones in the multiple drafting process is echoed in his appreciation of reverse outlining, where he can track the intent of each paragraph rather than how the paragraphs relate to each other, a point he makes explicitly as English 1102 closes:

Um, my theory of writing when I first started the class was very immature I remember describing it as just putting your emotions and thoughts on the paper I think was my first theory of writing and I think from the beginning of fall it’s gotten to where I understand the little parts of writing make up the important part of writing, so I think in that way it’s changed.

As the study concludes and Eugene is asked to comment retrospectively on what he learned in English 1102, he re-states not what he learned, but rather the prior knowledge on writing that he brought with him to college. He observes that, “For me, there wasn’t much of a difference between high school and college writing” and

Like I came from a really intensive writing program in high school, so coming into [the first-year comp] class wasn’t that different, so, um, I mean obviously any writing that I do will help me become better and hopefully I will progress and become better with each piece that I write, so in that regard I think it was helpful.

What thus seems to help, according to Eugene, is simply the opportunity to write, which will enable him to progress naturally through “any writing that I do.”

And not least, as the study closes, Eugene, in describing a conception of writing developed through an assemblage created by grafting the new key term “genre” onto an unconscious process resulting in writing that is dichotomously “good” or “bad,” repeats the definition he provided as English 1102 commenced:

I mean writing is, like, when you break it down it’s a lot more complex than what you describe it to me. I mean you can sit all day and talk about literary devices but it comes down to writing. Writing is, um, it’s more complex, so, it’s like anything, if you are going to break down, it’s going to be more complex than it seems. Writing is emotionally based. Good writing is good and bad writing is bad.

Writing here is complex, something to be analyzed, much like literature, “when you break it down.” But it’s also a practice: “you can sit all day and talk about literacy devices but it comes down to writing.” Likewise, the strategies Eugene appreciated—revising toward larger goals and reverse outlining to verify the points of individual paragraphs––fit with the assemblage model as well: they do not call into question an “unconscious” approach, but can be used to verify that this approach is producing texts whose component parts are satisfactory. Of course, this wasn’t the intent of the teacher introducing either the multiple drafting process or the reverse outlining strategy. But as Eugene makes use of prior knowledge, in an assemblage fashion, the conceptual model of unconscious writing he brought to college with him shapes his uptake of the curriculum more broadly, from key terms to process strategies.

Type Two: Remix

Students who believe that what they are learning differs from their prior knowledge in some substantive way(s) and value that difference behave differently. They begin to create a revised model of writing we characterize as a remix: prior knowledge revised synthetically to incorporate new concepts and practices into the prior model of writing. Remix, in this definition, isn’t a characteristic of hip-hop only or of modernism more generally, but a feature of invention with a long history:

Seen through a wider lens . . .remix—the combining of ideas, narratives, sources—is a classical means of invention, even (or perhaps especially) for canonical writers. For example, . . . as noted in Wikipedia, Shakespeare arguably “remixed” classical sources and Italian contemporary works to produce his plays, which were often modified for different audiences. Nineteenth century poets also utilized the technique. Examples include Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” which was produced in multiple, highly divergent versions, and John Keats’ La Belle Dame sans Merci, which underwent significant revision between its original composition in 1819 and its republication in 1820 (Remix). In sum, remixing, both a practice and a set of material practices, is connected to the creation of new texts (Yancey, Re-designing 6).

Here, we use remix with specific application to writing: a set of practices that links past writing knowledge and practice to new writing knowledge and practice, as we see in the experience of Alice.

Alice entered English 1102 with a conception of writing influenced by three sets of experience: preparing for and taking the Florida K-12 writing exams, known as the FCAT; completing her senior AP English class; and taking her English 1101 class, which she had completed in the summer before matriculating at Florida State. Alice had literally grown up as an “FCAT writer,” given that the writing curriculum in the state is keyed to these essay exams and for many if not most students, the writing exam is the curriculum (e.g., Scherff and Piazza). In her senior year, however, Alice enrolled in an AP English class, where she learned a different model of text that both built on and contrasted with her experience as an FCAT writer: “[my senior English teacher] explained his concept as instead of writing an intro, listing your three points, then the conclusion, to write like layers of a cake. Instead of spreading out each separate point . . . layer them.” The shift here, then, is one of remix: the arrangement of texts was to remain the same, while what happened inside the texts was to be changed, with Alice’s explanation suggesting that the shift was from a listing of points to an analysis of them. During the third experience, in the summer before her first year in college, Alice learned a new method of composing: she was introduced to “process writing,” including drafts, workshops and peer reviews.

When Alice entered English 1102, she defined writing as a Murray-esque exercise: “Writing,” Alice said, “is a form of expression that needs to have feeling and be articulate in order to get the writer’s ideas across. The writing also needs to have the author’s own unique voice,” an idea that provided something of a passport for her as she encountered new conceptions of writing located in key terms like rhetorical situation, context, and audience. In Alice’s retrospective account of English 1102, in fact, she focuses particularly on the conception of rhetorical situation as one both new to her and difficult to understand, in part because it functioned as something of a meta-concept: “Rhetorical situation had a lot of things involved in that. It was a hard concept for me to get at first but it was good.” By the end of the course, however, Alice was working hard to create an integrated model of writing that included three components: her own values, what she had learned during the summer prior to English 1102, and what she had learned in English 1102:

I still find writing to be a form of expression, it should have the author’s own voice and there should be multiple drafts and peer reviews in order to have the end result of a good and original paper. Along with that this year I learned about concepts such as rhetorical situation. . . . This opened me up to consider audience, purpose, and context for my writing. I need to know why I am writing and who I am writing to before I start. The context I am writing in also brings me to what genre I’m writing in.

Alice’s conception of writing here seems to rely on the layering strategy recommended by her AP teacher: voice, mixed with process, and framed rhetorically, defined here layer by layer.

As Alice continues into the term after she completes English 1102, two writing-related themes emerge for her. One: a key part of the process for Alice that begins to have new salience for her is reflecting on her writing, both as she drafts and after she completes a text. Two: she finds that the study itself has helped her develop as a writer but that she needs more time and more writing activity to make sense of all that she’s been offered in English 1102.

In English 1102, Alice had been asked to reflect frequently: in the midst of drafting; at the end of assignments; and at the end of the course itself in a reflection-in-presentation where she summarized what she had learned and also theorized about writing. These reflective practices she found particularly helpful and, in the next term, when she wrote assignments for her humanities and meteorology classes, she continued to practice a self-sponsored reflection: it had become part of her composing process. As she explains, her own sense is that through reflection, she is able to bring together the multiple factors that contribute to writing:

I do know that I really liked reflection, like having that because I haven’t done that before. And whatever term was writing with a purpose and I like that so I guess writing with some purpose. Like when you are done writing you do reflection because before I would be done with a writing and go to the next one and so then in between we go over each step or throughout.

As the study concluded, Alice linked reflection and rhetorical situation as the two most important concepts for writing that she learned in English 1102, but as she did earlier, she also includes a value of her own, in this case “being direct,” into a remixed model of writing:{5}

Two of the words I would use to describe my theory of writing would be the key terms, rhetorical situation, reflection and the last that isn’t would just be being direct. Rhetorical situation encompasses a lot about anybody’s theory of writing. It deals with knowing the purpose of my writing, understanding the context of my writing, and thinking about my audience. I chose being direct for lack of a better term. I don’t think my writing should beat around the bush. It should just say what needs to be said and have a purpose. As for reflection that’s something we do in life and not just writing. In the context of writing it really helps not just as a review of grammar or spelling errors but as a thought back on what I was thinking about when I wrote what I wrote, and that could change as I look back on my writing.

Being direct, of course, was Alice’s contribution to a curricular-based model of writing informed by reflective practice and rhetorical situation. Reflection she defines as a “thought back,” a variation of the “talk backs” that students were assigned in English 1102, here a generalized articulation of a meta-cognitive practice helping her “change as I look back on my writing.” In addition, Alice works toward making reflection her own as she theorizes about it––“that’s something we do in life and not just writing”—in the process seeing it as a life-practice as well as a writing practice. More generally, what we see here is that Alice is developing her own “remixed” model of composing, combining her values with curricular concepts and practices. Not least, reflection was thus more than an after-the-fact activity for Alice; rather, it provided a mechanism for her to understand herself as a learner and prepare for the future whether it was writing or another activity.

Alice, however, is also aware of the impact of the study and of the need for more time to integrate what she has learned in English 1102 into her model and practice of writing. On the one hand, she seems to appreciate the study since, in her view, it functions as a follow-up activity extending the class itself, which is particularly valuable as she takes up new writing tasks the next semester:

I feel as though I forget a lot about a class after I take it. I definitely don’t remember everything about my English class, but I feel I remember what will help me the most in my writing and I think that information will stay with me. This study has helped me get more from the class than just taking it and after not thinking about it anymore. The study helped me in a way to remind me to think about what we went over in English as I wrote for my other classes.

On the other hand, Alice understands that she has been unable to use all that was offered in English 1102:

I feel like I haven’t used everything; there were a lot of terms that we went over I don’t use and there are some that I do and those are the ones that [the teacher] used the most anyways. I feel like this has helped me remember those that I will use and I feel like this has helped me retain a lot of information and now I have had to write a lot more besides our class and the stuff I gave to you. I was still thinking about what we did in that comp class, so it has really helped me. But I still think I could use a lot more experiences with writing papers and getting more from a college class, I mean like getting away from the FCAT sound. I wrote like that until 10th grade.

Alice hopes that she has identified the best terms from the class and thinks that she has, given that “those are the ones that the teacher used the most,” which repetition was, as she observes, one reason she probably remembers them. But because of the interviews, she “was still thinking about what we did in the comp class”: she is continuing to think about the terms more intentionally than she might have had no interviews taken place. But as important, Alice believes that she “could use a lot more experiences with writing papers and getting more from a college class,” here pointing to the need to get “away from the FCAT.” Given that Alice “wrote like that until 10th grade,” “getting away from the FCAT sound” is more difficult than it might first appear.

In sum, there is much to learn from Alice’s experience. Through her integration of her own values, prior knowledge, and new knowledge and practice, we see how students develop a remix model of composing, one that may change over time but that remains a remix. We see as well how a composing practice like reflection can be generalized into a larger philosophy of reflection, one more characteristic of expertise. And, not least, we see, through a student’s observations, how a term that we see as a single concept functions more largely, as a meta-concept, and we see as well how hard it can be to remix prior knowledge, especially when that prior knowledge is nearly deterministic in its application and impact.{6}

Critical Incidents: Motivating New Conceptions and Practices of Composing

Often students, both in first-year composition and in other writing situations, encounter a version of what’s called, in fields ranging from air traffic control and surgery to teaching, a “critical incident”: a situation where efforts either do not succeed at all or succeed only minimally. What we have found is that writing students also encounter critical incidents, and some students can be willing or able to let go of prior knowledge as they re-think what they have learned, revise their model and/or conception of writing, and write anew. In other words, the set-backs motivated by critical incidents can provide the opportunity for conceptual breakthroughs, as we shall see in the case of Rick.

The surgeon Atul Gawande describes critical incidents as they occur in surgery and how they are later understood in his account of medical practice titled Complications. Surgical practice, like air traffic control, routinely and intentionally engages practitioners in a collective reviewing of what went wrong—in surgery, operations where the patient died or whose outcome was negative in other ways; in air traffic control, missteps large (e.g., a crash) and small (e.g., a near miss)—in the belief that such a review can reduce error and thus enhance practice. Accordingly, hospital-based surgeons meet weekly for the Morbidity and Mortality Conference, the M&M for short, its purpose both to reduce the incidence of mistakes and to make knowledge. As Gawande explains,

There is one place, however, where doctors can talk candidly about their mistakes, if not with the patients, then at least with one another. It is called the Morbidity and Mortality Conference—or, more simply, M & M—and it takes place, usually once a week, at nearly every academic hospital in the country. . . . Surgeons, in particular, take the M & M seriously. Here they can gather behind closed doors to review the mistakes, untoward events, and deaths that occurred on their watch, determine responsibility, and figure out what to do differently next time. (57-58)

The protocol for the M&M never varies. The physician in charge speaks for the entire team, even if she or he wasn’t present at the event under inquiry. In other words, a resident might have handled the case, but the person responsible—called, often ironically, the attending physician—speaks. First presented is information about the case: age of patient, reason for surgery, progress of surgery. Next the surgeon outlines what happened, focusing on the error in question; that there was an error is not in question, so the point is to see if that error might have been discerned more readily and thus to have produced a positive outcome. The surgeon provides an analysis and responds to questions, continuing to act as a spokesperson for the entire medical team. The doctor members of the team, regardless of rank, are all included but do not speak; the other members of the medical team, including nurses and technicians, are excluded, as are patients. The presentation concludes with a directive about how such prototypic cases should be handled in the future, and it’s worth noting that, collectively, the results of the M&Ms have reduced error.

Several assumptions undergird this community of practice, in particular assumptions at odds with those of compositionists. We long ago gave up a focus on error, for example, in favor of the construction of a social text. Likewise, we might find it surprising that the M&M is so focused on what went wrong when just as much might be learned by what went right, especially in spite of the odds, for instance, on the young child with a heart defect who surprises by making it through surgery. Still, the practice of review in light of a critical incident suggests that even experts can revise their models when prompted to do so.

This is exactly what happened to Rick, a first-year student with an affection for all things scientific, who experienced a misfit between his prior knowledge and new writing tasks as he entered English 1102. Rick identified as a novice writer in this class, in part because he was not invested in writing apart from its role in science. A physics and astrophysics major, he was already working on a faculty research project in the physics laboratory and was planning a research career in his major area. He professed:

I am a physics major so I really like writing about things I think people should know about that is going on in the world of science. Sometimes it’s a challenge to get my ideas across to somebody that is not a science or math type, but I enjoy teaching people about physics and the world around them.

Rick credited multiple previous experiences for his understanding of writing, including his other high school and college courses; in addition, he mentioned watching YouTube videos of famous physicists lecturing and reading Einstein’s work. He also believed that reading scientific materials had contributed to his success in writing scientific texts: “I think I write well in my science lab reports because I have read so many lectures and reports that I can just kind of copy their style into my writing.”{7}

Rick’s combination of prior knowledge and motivation, however, didn’t prove sufficient when he began the research project in English 1102. He chose a topic with which he was not only familiar but also passionate, quantum mechanics, his aim to communicate the ways in which quantum mechanics benefits society. He therefore approached the research as an opportunity to share what he knew with others, rather than as inquiry into a topic and discovery of what might be significant. He also had difficulty making the information clear in his essay, which he understood as a rhetorical task: “The biggest challenge was making sure the language and content was easy enough for someone who is not a physics major to understand. It took a long time to explain it in simple terms, and I didn’t want to talk down to the audience.” In this context, Rick understood the challenge of expressing the significance of his findings to his audience, which he determined was fellow college students. But the draft he shared with his peers was confusing to them, not because of the language or information, as Rick had anticipated, but instead because of uncertainty about key points of the essay and about what they as readers were being asked to do with this information.

As a self-indentified novice, however, Rick reported that this experience taught him a valuable lesson about audience. “I tried to make it simple so . . . my classmates would understand it, but that just ended up messing up my paper, focusing more on the topic than on the research, which is what mattered. I explained too much instead of making it matter to them.” Still, when the projects were returned, he admitted his surprise at the evaluation of the essay but was not willing to entertain the idea that his bias or insider knowledge about quantum mechanics had prevented his inquiry-based research:

After everyone got their papers back, I noticed that our grades were based more on following the traditional conventions of a research paper, and I didn’t follow those as well as I could have. I don’t really see the importance of following specific genre conventions perfectly.

In the next semester, however, these issues of genre and audience came together in a critical incident for Rick as he wrote his first lab report for chemistry. Ironically, Rick was particularly excited about this writing because, unlike the writing he had composed in English 1102, this was science writing: a lab report. But as it turned out, it was a lab report with a twist: the instructor specified that the report have a conclusion to it that would link it to “everyday life”:

We had to explain something interesting about the lab and how that relates to everyday life. I would say it is almost identical to the normal introduction one would write for a paper, trying to grab the reader’s attention, while at the same time exploring what you will be talking about.

Aware of genre conventions and yet in spite of these directions for modification, Rick wrote a standard lab report. In fact, in his highlighting of the data, he made it more lab-report-like rather than less: “I tried to have my lab report stick out from the others with better explanations of the data and the experiment.” The chemistry instructor noticed, and not favorably: Rick’s score was low, and he was more than disappointed. Eager to write science, he got a lower grade than he did on his work in English 1102, and it wasn’t because he didn’t know the content; it was because he hadn’t followed directions for writing.

This episode constituted a critical incident for Rick. Dismayed, he went to talk to the teacher about the score; she explained that he indeed needed to write the lab report not as the genre might strictly require, but as she had adapted it. Chastened, he did so in all the next assigned lab reports, and to good effect: “My lab reports were getting all the available points and they were solid too, very concise and factual but the conclusions used a lot of good reflection in them to show that the experiments have implications on our lives.” The ability to adapt to teacher directions in order to get a higher grade, as is common for savvy students, doesn’t in and of itself constitute a critical incident; what makes it so here is Rick’s response and the re-seeing that Rick engages in afterwards. Put differently, he begins to see writing as synthetic and genres as flexible, and in the process, he begins to develop a more capacious conception of writing, based in part on his tracing similarities and differences across his own writing tasks past and present.

This re-seeing operates at several units of analysis. On the first level, Rick articulates a new appreciation for the value of the assignment, especially the new conclusion, and the ways he is able to theorize it: “I did better on the conclusions when I started to think about the discourse community and what is expected in it. I remembered that from English 1102, that discourse community dictates how you write, so I thought about it.” On another level, while Rick maintains that the genres were different in the lab courses than in 1102, as in fact they are, he is able to map similarities across them:

One similarity would be after reading an article in 1102 and writing a critique where we had to think about the article and what it meant. This is very similar to what we do in science: we read data and then try to explain what it means and how it came about. This seems to be fundamental to the understanding of anything really, and is done in almost every class.

This theorizing, of course, came after the fact of the critical incident, and one might make the argument that such theorizing is just a way of coming to terms with meeting the teacher’s directions. But as the term progressed, Rick was able to use his new understanding of writing—located in discourse communities and genres and keyed to reading data and explaining them—as a way to frame one of his new assignments, a poster assignment. His analysis of how to approach it involved his taking the terms from English 1102 and using them to frame the new task:

I have this poster I had to create for my chemistry class, which tells me what genre I have to use, and so I know how to write it, because a poster should be organized a certain way and look a certain way and it is written to a specific audience in a scientific way. I wouldn’t write it the same way I would write a research essay – I’m presenting the key points about this chemistry project, not writing a lot of paragraphs that include what other people say about it or whatever. The poster is just the highlights with illustrations, but it is right for its audience. It wasn’t until I was making the poster that I realized I was thinking about the context I would present it in, which is like rhetorical situation, and that it was a genre. So I thought about those things and I think it helped. My poster was awesome.

Here we see Rick’s thinking across tasks, genres, and discourse communities as he maps both similarities and differences across them. Moreover, as he creates the chemistry poster, he draws on new prior knowledge, that prior knowledge he developed in his English 1102 class, this a rhetorical knowledge keyed to three features of rhetorical situations generally: (1) an understanding of the genre in which he was composing and presenting, (2) the audience to whom he was presenting, and (3) the context in which they would receive his work. Despite the fact that this chemistry poster assignment was the first time he had composed in this genre, he was successful at creating it, at least in part because he drew on his prior knowledge in a useful way, one that allowed him to see where similarities provided a bridge and differences a point of articulation.{8}

All this, of course, is not to say that Rick is an expert, but as many scholars in composition, including Sommers and Saltz, and Beaufort, as well as psychologists like Marcia Baxter-Magolda argue, students need the opportunity to be novices in order to develop toward expertise. This is exactly what works for Rick when the challenges in college writing, in both English 1102 and more particularly in chemistry, encourage him to think of himself as a novice and to take up new concepts of writing and new practices. Moreover, the critical incident prompts Rick to develop a more capacious understanding of writing, one in which genre is flexible and the making of knowledge includes application. Likewise, this new understanding of writing provides him with a framework that he can use as he navigates new contexts and writing tasks, as he does with the chemistry poster.

If indeed some college students are, at least at the beginning of their postsecondary career, boundary guarders, and others boundary crossers, and if we want to continue using metaphors of travel to describe the experience of college writers, then we might say that Rick has moved beyond boundary crossing: as a college writer, he has taken up residence.

Concluding Thoughts

Our purpose in this article is both to elaborate more fully students’ uses of prior knowledge and to document how such uses can detract from or contribute to efficacy in student writing. As important, this analysis puts a face on what transfer in composition as “an active, dynamic process” looks like: it shows students working with such prior knowledge in order to respond to new situations and to create their own new models of writing. As documented here, both in the research literature and in the students’ own words, students are likely to begin college with absent prior knowledge, particularly in terms of conceptions of writing and models of non-fiction texts. Once in college, students tap their prior knowledge in one of three ways. In cases like Eugene’s, students work within an assemblage model, grafting pieces of new information—often key terms or process strategies––onto prior understandings of writing that serve as a foundation to which they frequently return. Other students, like Alice, work within a remix model, blending elements of both prior knowledge and new knowledge with personal values into a revised model of writing. And still other students, like Rick, use a writing setback, what we call a critical incident, >as a prompt to re-theorize writing and to practice composing in new ways.

The prototype presented here is a basic outline that we hope to continue developing; we also think it will be helpful for both teaching and research. Teachers, for example, may want to ask students about their absent prior knowledge and invite them to participate in creating a knowledge filling that absence. Put differently, if students understand that there is an absence of knowledge that they will need—a perception which many of them don’t seem to share—they may be more motivated to take up a challenge that heretofore they have not understood. Likewise, explaining remix as a way of integrating old and new, personal and academic knowledge and experience into a revised conception and practice of composing for college may provide a mechanism to help students understand how writing development, from novice to expertise, works and, again, how they participate in such development. Last but not least, students might be alerted to writing situations that qualify as critical incidents; working with experiences like Rick’s, they may begin to understand their own setbacks as opportunities. Indeed, we think that collecting experiences like Rick’s (of course, with student permissions) to share and consider with students may be the most helpful exercise of all.

There is more research on student uptake of prior knowledge to conduct as well, as a quick review of Rick’s experience suggests. The critical incident motivates Rick to re-think writing, as we saw, but it’s also so that Rick is a science major and, as he told us, science not only thrives on error, but also progresses on the basis of error. Given his intellectual interests, Rick was especially receptive to a setback, especially—and it’s worth noting this—when it occurred in his preferred field, science. For one thing, Rick identifies as a scientist, so he is motivated to do well. For another and more generally, failure in the context of science is critical to success. Without such a context, or even an understanding of the context as astute as Rick’s, other students may look upon such a setback as a personal failure (and understandably so), which view can prompt not a re-thinking, but rather resistance. In other words, we need to explore what difference a student’s major, and the intellectual tradition it represents, makes in a student’s use of prior knowledge. Likewise, we need to explore other instantiations of the assemblage model of prior knowledge uptake as well as differentiations in the remix model. And we need to explore the relationship between these differentiations and efficacy: surely some are more efficacious than others. And, not least, we need to explore further what happens to those students, like Rick, who through critical incidents begin to take up residence as college composers.

Notes

- In this article, we draw on two studies of transfer, both connected to a Teaching for Transfer composition curriculum for first-year students: Liane Robertson’s The Significance of Course Content in the Transfer of Writing Knowledge from First-Year Composition to other Academic Writing Contexts and Kara Taczak’s Connecting the Dots: Does Reflection Foster Transfer? (Return to text.)

- A more robust picture includes an additional dimension of prior knowledge: what we call a point of departure. We theorize that students make progress, or not, in part relative to their past performances as writers—as represented in external benchmarks like grades and test scores. See Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Cultures of Writing, forthcoming. (Return to text.)

- The travel metaphor in composition has been variously used and critiqued: for the former, see Gregory Clark; for the latter, see Nedra Reynolds. Regarding the use of such a metaphor in the transfer literature in college composition, it seems first to have been used by McCarthy in her reference to students in strange lands. Based on this usage and on our own studies, we theorize that what students bring with them to college, by way of prior knowledge, is a passport that functions as something of a guide. As important, when students use the guide to reflect back rather than to cast forward, it tends to replicate the past rather than to guide for the future, and in that sense, Reynolds’s observations about many students replicating the old in the new are astute. See our Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Cultures of Writing, forthcoming. (Return to text.)

- According to How People Learn, prior knowledge can function in three ways, as we have seen. But when the prior knowledge is a misfit, it may be because the “correct” prior knowledge, or knowledge that is more related, isn’t available, which leads us to conceptualize absent prior knowledge. For a similar argument in a very different context, materials science, see Krause et al. (Return to text.)

- Alice’s interest in “being direct,” of course, may be a more specific description of her voice, whose value she emphasized upon entering English 1102. (Return to text.)

- Ironically, the function of such tests according to testing advocates, is to help writers develop; here the FCAT seems to have mis-shaped rather than to have helped, as Alice laments. (Return to text.)

- Rick’s sense of the influence of his reading on his conception of text, of course, is the point made above about students’ reading practices. (Return to text.)

- This ability to read across patterns, discerning similarities and differences, that we see Rick engaging in, is a signature practice defining expertise, according to How People Learn. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Applebee, Arthur, and Judith Langer. What’s Happening in the Teaching of Writing? English Journal 98.5 (2009): 18-28. Print.

-----. A Snapshot of Writing Instruction in Middle Schools and High Schools. English Journal 100.6 (2011): 14–27. Print.

Baxter-Magolda, Marcia B. Making Their Own Way: Narratives for Transforming Higher Education to Promote Self-Development. Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2001. Print.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Logan: Utah State UP, 2007. Print.

Bergmann, Linda S., and Janet S. Zepernick. Disciplinarity and Transference: Students' Perceptions of Learning to Write. WPA: Writing Program Administration 31.1/2 (2007): 124-49. Print.

Beyer, Catharine Hoffman, Andrew T. Fisher, and Gerald M. Gillmore. Inside the Undergraduate Experience, the University of Washington's Study of Undergraduate Learning. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing, 2007. Print.

Bird, Barbara. Writing about Writing as the Heart of a Writing Studies Approach to FYC: Response to Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle, ‘Teaching about Writing/Righting Misconceptions’ and to Libby Miles et al., ‘Thinking Vertically’. College Composition and Communication 60.1 (2008): 165-71. Print.

Bransford, John D., James W. Pellegrino, and M. Suzanne Donovan, eds. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Washington, DC: National Academies P, 2000. Print.

Britton, James, et al. The Development of Writing Abilities (11–18), London: MacMillan Education, 1975. Print.

Carter, Michael. The Idea of Expertise: An Exploration of Cognitive and Social Dimensions of Writing. College Composition and Communication 41.3 (1990): 265-86. Print.

Clark, Gregory. Writing as Travel, or Rhetoric on the Road. College Composition and Communication 49.1 (1998): 9-23. Print.

Detterman, Douglas K., and Robert J. Sternberg, eds. Transfer on Trial: Intelligence, Cognition, and Instruction. New Jersey: Ablex, 1993. Print.

Dew, Debra. Language Matters: Rhetoric and Writing I as Content Course. WPA: Writing Program Administration 26.3 (2003): 87–104. Print.

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning ‘First-Year Composition’ as Introduction to Writing Studies. College Composition and Communication 58.4 (2007): 552-84. Print.

Fulkerson, Richard. Summary and Critique: Composition at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century. College Composition and Communication 56.4 (2005): 654-87. Print.

Gawande, Atul. Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. New York: Holt/Picador, 2002. Print.

Jarratt, Susan, et al. Pedagogical Memory and the Transferability of Writing Knowledge: an Interview-Based Study of Juniors and Seniors at a Research University. Writing Research Across Borders Conference. University of California Santa Barbara. 22 Feb 2008. Presentation.

Krause, Steve, et al. The Role of Prior Knowledge on the Origin and Repair of Misconceptions in an Introductory Class on Materials Science and Engineering Materials Science. Proceedings of the Research in Engineering Education Symposium 2009, Palm Cove, QLD. Web.

Langer, Judith A., and Arthur N. Applebee. How Writing Shapes Thinking: A Study of Teaching and Learning. Urbana, IL: NCTE P, 1987. Print.

Lenhart, Amanda, et al. Writing, Technology, and Teens. Washington, D.C.: Pew Internet & American Life Project, April 2008. Web. 12 Jan 2012.

McCarthy, Lucille. A Stranger in Strange Lands: A College Student Writing across the Curriculum. Research in the Teaching of English 21.3 (1987): 233-65. Print.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. Transfer of Learning. International Encyclopedia of Education. 2nd ed. Oxford: Pergamon P, 1992. 2-13. Print.

Prather, Dirk C. Trial and Error versus Errorless Learning: Training, Transfer, and Stress. The American Journal of Psychology 84.3 (1971): 377-86. Print.

Reiff, Mary Jo, and Anis Bawarshi. Tracing Discursive Resources: How Students Use Prior Genre Knowledge to Negotiate New Writing Contexts in First-Year Composition. Written Communication 28.3 (2011): 312–37. Print.

Reynolds, Nedra. Geographies of Writing: Inhabiting Places and Encountering Difference. Southern Illinois University Press, 2004. Print.

Robertson, Liane. The Significance of Course Content in the Transfer of Writing Knowledge from First-Year Composition to other Academic Writing Contexts. Diss. Florida State University, 2011. Print.

Robinson, Tracy Ann, and Vicki Tolar Burton. The Writer’s Personal Profile: Student Self Assessment and Goal Setting at Start of Term. Across the Disciplines 6 (Dec 2009). Web. 12 Jan 2012.

Russell, David R. Rethinking Genre and Society: An Activity Theory Analysis. Written Communication 14.4 (1997): 504-54. Print.

Russell, David R., and Arturo Yañez. ‘Big Picture People Rarely Become Historians’: Genre Systems and the Contradictions of General Education. Writing Selves/Writing Societies: Research From Activity Perspectives. Ed. Charles Bazerman and David R. Russell. Fort Collins, CO: WAC Clearinghouse and Mind, Culture and Activity, 2002. Web. 12 Jan 2012.

Scherff, Lisa, and Carolyn Piazza. The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: A Survey of High School Students‘ Writing Experiences. Research in the Teaching of English 39.3 (2005): 271-304. Print.

Slomp, David H., and M. Elizabeth Sargent. Responses to Responses: Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle’s ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions.’ College Composition and Communication 60.3 (2009): 595-96. Print.

Sommers, Nancy, and Laura Saltz. The Novice as Expert: Writing the Freshman Year. College Composition and Communication 56.1 (2004): 124-49. Print.

Taczak, Kara. Connecting the Dots: Does Reflection Foster Transfer? Diss. Florida State University, 2011. Print.

Thorndike, E. L., and R. S. Woodworth. The Influence of Improvement in One Mental Function upon the Efficiency of Other Functions. Psychological Review 8 (1901): 247–61. Print.

Vander Lei, Elizabeth, and Bonnie LenoreKyburz, eds. Negotiating Religious Faith in the Composition Classroom. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook, 2005. Print.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Understanding ‘Transfer’ from FYC: Preliminary Results of a Longitudinal Study. WPA: Writing Program Administration 31.1–2 (2007), 65–85. Print.

Wikipedia contributors. William Shakespeare. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 4 Jan. 2012. Web. 12 Jan. 2012.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, Ed. Delivering College Composition: The Fifth Canon. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook, 2006. Print.

-----. Re-designing Graduate Education in Composition and Rhetoric: The Use of Remix as Concept, Material, and Method. Computers and Composition 26.1 (2009): 4-12. Print.

-----, Robertson, Liane, and Taczak, Kara. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Cultures of Writing. Forthcoming.

Prior Knowledge and Its Role in Transfer from Composition Forum 26 (Fall 2012)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/prior-knowledge-transfer.php

© Copyright 2012 Liane Robertson, Kara Taczak, and Kathleen Blake Yancey.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 26 table of contents.