Composition Forum 51, Spring 2023

http://compositionforum.com/issue/51/

Enrolling or Serving?: Interest Convergence in Institutional Support of Writing Programs at HSIs

Abstract: Much of the research in composition about Hispanic-serving institutions focuses on the tripartite of writing program administrators, faculty, and students and the complexities of multilingual learner pedagogies. This article draws on conversational interview methods and data to analyze the servingness of three Floridian HSIs through critical race theory’s interest convergence thesis. The interest convergence thesis advances that institutional efforts toward racial equality will persist only so far as those efforts also preserve the interests of racial dominance in social institutions. Guided by an institutional critique and racial methodological approach, this interest convergence analysis examines the impact of culturally White institutional ideologies on general education writing curriculum choices, professional development, and the ethnic-racial cultural composition of institutional governance. Interviews with WPAs from the three institutions detail how the institutional epistemologies of literacy affect their decisions and opportunities for Latinx-centric programmatic servingness at their HSIs.

“This goal of being inclusive and recognizing diversity and thinking about social justice issues, I think those are core beliefs that really are addressing exactly what our students need.”

WPA, Private State University, Florida

At Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs), it can be difficult to pinpoint what exactly it means to serve Latinx student populations, mostly because those in serving positions don't recognize the cultural specificities across the multitude of Latin American, Hispaniola, and other Latinx communities. This factor can pose a particular hindrance for some Latinx students, if, as Michelle Hall Kells claims, “it is all about belonging” (Foreword ix). This article shares one part of a pilot research study that interrogates the serving part of three Floridian HSIs by considering what the institutions and writing programs at these HSIs are doing to serve their Latinx populations. While the goal of the full study is to examine ethnic-racial cultural servingness at a wider sample of HSIs in the region, here, I focus on the impact of institutional interests and efforts on writing program serving practices.

The interests of institutions are aligned with dominant socioeconomic, linguistic, racial, and heteronormative cultural dispositions. All serving in this context is concerned with low cultural competence and high institutional outcomes (Garcia). As of Fall 2020, the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities lists twelve Florida higher education institutions as HSIs, so this moment is optimum to explore how a crucial segment of higher education—the first-year writing (FYW) program and courses—has responded to this recasting of the student demographic or how the institutions plan to respond. Enrollment of Latinx students in the Florida College System increased by just over 12% from 2016 to 2020, with at least a 2% increase in enrollment each fall until the year of COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (Florida Department of Education). This is reflected by the critical juncture in my institution’s recent designation as an HSI, indicating that more than 25% of the student population identifies as “Hispanic” in some way. This study was launched at this critical point. By studying three institutions in the state, the study represents a quarter of the twelve colleges and universities defined as Hispanic-serving in Florida.

Cristina Kirklighter et al. stress that HSIs differ from HBCUs (historically Black colleges and universities) in that the HSI mission has always been linked to enrollment as opposed to serving a particular community of students (3). These institutions use the descriptor Hispanic-serving to distinguish their enrollment demographics against predominantly White institutions, HBCUs, and others types of MSIs. However, as Michelle Hall Kells clarifies in the foreword to Teaching Writing with Latino/a Students: Lessons Learned at Hispanic-Serving Institutions, Hispanic has become an inaccurate but convenient term to reference a portion of our student bodies who might personally refer to themselves as “Chicano, Chicana, Latino, Latina, Hispano, or Hispana, or perhaps Mexican-American, Puerto Rican, or Cubano, Cubana” (xii). Because I recognize the complex ethnic-racial-gender constructions of these communities, I use the gender-fluid descriptor “Latinx” to refer collectively to this population. I understand that neither is this term fully inclusive for these communities. I will continue to refer to the institutions here as Hispanic-serving, the term coined by the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities in 1986 (Santiago Inventing), in order to emphasize the failure of this term to include the breadth of these communities. Without a true understanding of students’ cultural community contexts, supported by curricular considerations, professional development, and the ethnic-racial cultural composition of institutional governance, these institutions will remain Hispanic-enrolled institutions, serving in name only.

To show how these components interact in a way that misses the mark for serving Latinx students, I harness critical race theory’s interest convergence thesis to frame an institutional critique and analysis of how they operate within the institution. Interest convergence based on institutional goals or outcomes results in enrolling more Latinx student writers in FYW programs but not truly serving them. As much as administrators may want to serve Latinx students, as demonstrated in the opening epigraph, they are limited by low cultural knowledge or fidelity to dominant cultural interests. Institutions that serve effectively move past interest convergence to cultural sustainability and empowerment.

Critical Race Theory Interest Convergence Thesis and Serving Institution and Student Cultural Interests

“A lot of my students call me the campus godfather ... when they show up here. I never understood this whole idea of the kid is completely by themselves because they’re not independent in any other way.”

Department Chair, Faith-based HSI

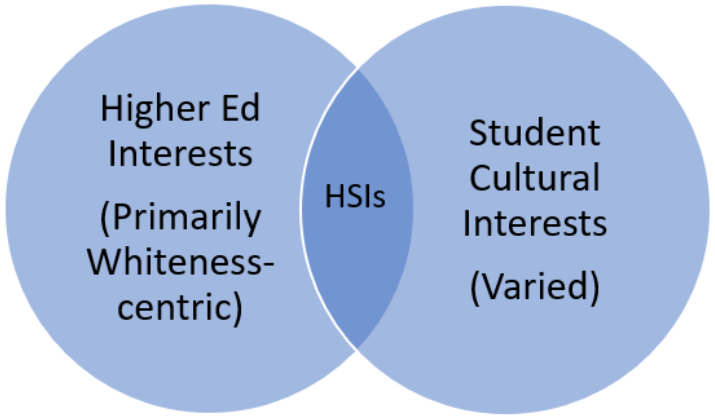

Higher education’s academic and social development is designed to sustain institutional raciolinguistic interests, which serve the ideals of those invested in preserving the neoliberal, Euro-American heteronormative patriarchal status quo (Collins; Paris and Alim). Now see, the leading members of this culture may claim to seek and maintain diversity, equity, or inclusion, but that is only so far as these ideals help it meet its bottom line. As a cis-woman assistant professor of Black African descent, who’d grown up in a fully Black American underclass urban community but was bussed to a school district in an all-White American suburban community, I am well-versed at recognizing interest convergence in education spaces. The critical race theory interest convergence thesis postulates that policy efforts supporting racial equality for Blacks and other subjugated racial formations will support it only so far as those efforts also maintain the interests of the racially dominant in society. Foundational critical race theory legal scholar, Derrick Bell, applies this thesis to explain the popular court opinion behind Brown vs. Board of Education and legal cases following its precedent. Racial interest convergence is the theory that people of the dominant White cultural identity will struggle for racial equality so long as it keeps the dominant racial culture in social power. Basically, the dominant culture’s interest of remaining dominant must converge with the subordinated culture’s interest of gaining equal social, political, and economic standing. With the interest convergence thesis, I am able to analyze just how closely the institutions’ interests align with student communities’ cultural interests as well as the effect of outlying interests on both sides. HSIs might be viewed as existing within the nexus of this convergence in higher education, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interest Convergence Diagram of Hispanic-Serving Institutions

Enrique Alemán, Jr. and Sonya M. Alemán argue that interest convergence theory has been misapplied in education as an approach to seeking justice rather than a critique of dominant approaches to racial justice. Outside of Brown, this theory supports other education system interrogations, including those put forth by LatCrit in education theorists, or theorists of Latinx critical race studies in education. LatCrit aims to consider the ways critical race theory can encompass more than Black/White race relations to center a contextualized understanding of Latinx communities’ diverse ways of being among inter-group relations and push for social justice and activism (LatCrit; Solorzano & Yosso). Dolores Delgado Bernal synthesizes LatCrit in education as “a framework that challenges the dominant discourse on race, gender, and class” in education policy and theory and recognizes that educational systems “operate in contradictory ways with their potential to oppress and marginalize and their potential to emancipate and empower” (109). LatCrit compositionist Aja Y. Martinez has shown how the discourse community of Chicanx first-generation students tend to “rely on dominant color-blind ideology concerning freedom of choice and equal opportunity to explain their positions within the academy,” something Martinez argues is a part of the empire of force: “an ideology subscribed to and maintained by a dominating presence that affects everyday life and circumstance” (586). This cultural practice often results in an institutionally dominant converging of interests in which the ethnic-cultural representations of Latinx and other BIPOC students strain against who the institution suggests they should be. This discourse community of students often turn to race-evasive rationalizations, such as “abstract liberalism” and “cultural racism”{1} to “discard their own cultural and ethnic representation” of language and literacies (585) with the intent to replace it with institution-sanctioned linguistic-literacy representations.

E. Domínguez Barajas helps us understand the HSI-focused approaches combating these assimilationist practices. One of these includes the bilingual composition course from Isis Artze-Vega et al., or “classes in which an instructor who is unfamiliar with the student’s home language or dialect” (cited in Barajas 217) takes on the position of linguistic novice and students with linguistic authority are encouraged to speak, read, and write in Spanish and English separately and together, as matches their linguistic profiles. There is also Aydé Enríquez-Loya's “interdiscursive paradigm that blurs the line between literature and rhetoric ... and between societal and institutional demands” with rhetorical traditions like storytelling to privilege “personal narratives ... [which] must not be displaced by the conventions of academic discourse” (cited in Barajas 218). The interest convergence thesis, as supplemented by LatCrit, is particularly adaptable to the institutional critique of HSIs due to their convergent position in American higher education.

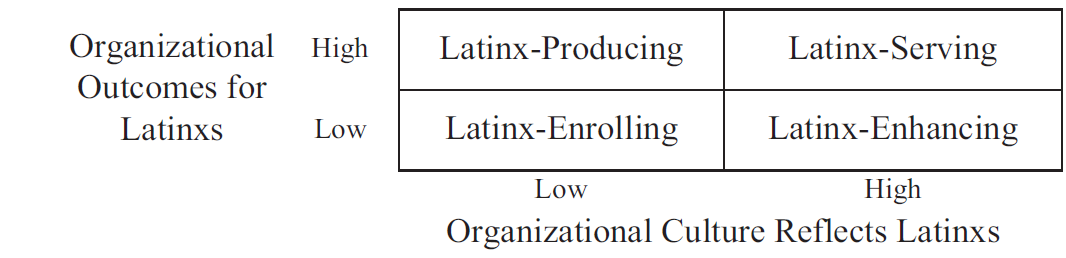

For the sake of this interest convergence analysis, I formulate raciolinguistic cultural interests as the preferred ways of doing, being, and navigating the social world, through the rhetorical and literate means of expression and consumption developed from linguistic and racial cultural contexts. The institutional cultural interests of HSIs preserve dominant American English and other culturally dominant raciolinguistic orientations with the premise/promise of preparing students for the rhetorical aptitude to engage with the prevailing social culture. Gina A. Garcia argues that the one issue to consider in the servingness of Latinx students at HSIs is that of organizational identity. I add that it is also an issue of how much the interests of the Latinx populations at these institutions intersect with the organizational interests of the institutions. To do this, I consider Garcia's typology of “HSI organizational identities” (121S), found in Figure 2., in conjunction with the interest convergence model, exemplified in Figure 1. As shown in the illustration, Garcia suggests that HSIs can be typified along two axes: “organizational outcomes for Latinx students” or metrics that institutions use to measure success and “organizational culture that facilitates outcomes for Latinx students” or the deeply entrenched organizational ideologies (121S). Serving Latinx students in writing programs will not produce the same outcomes across institutions, because what it means to do so varies with local contexts.

Figure 2. Garcia’s Dimensions of HSI Organizational Identities

Source: Garcia, Gina, “Defined by Outcomes or Culture? Constructing an Organizational Identity for Hispanic-Serving Institutions,” Apr. 2017, figure 1.

To understand their organizational identity in serving students across the Latinx communities at these institutions (Garcia), universities and colleges should consider how well they are serving Latinx students’ ethnic-cultural interests intersectionally (Crenshaw; Collins) in the same ways they serve the institution’s Euro-Western, or whiteness-centric, ethnic-cultural interests.

Related to the literacy work of writing programs, culturally White raciolinguistic interests might include cultural assimilation through linguistic colonization, individualism, universalism, decontextualization, and formalism. Culturally Latinx interests in this area manifest in discourse through the interest of community belonging described earlier by Kells, for one. Communities display this interest through discursive acts such as integrating border rhetorics and code-meshing (Young), making use of mainstream discourses for their own purposes, often representative of such border or meshed identities. Audiences and rhetors often prefer subtlety in communication through visual or codex rhetorics and communication practices meant to preserve community. Institutions, however, frequently disregard these interests as a failure to adopt dominant literacy and language practices, even at HSIs.

Students transitioning to college for the first time in particular often find themselves in a moment of reckoning their racial-culture-related values with their academic and professional-related goals (Tatum). Garcia suggests that each HSI needs to figure out its organizational identity as Latinx-serving so that it may “determine how to support the educational growth and development of the fastest growing racial/ethnic group in higher education in the 21st century” (112S) in ways that many have failed to do so thus far. The primary cultural function of colleges and universities is to acculturate learners to cultural sameness, so the institutions have little external incentive to account for students' extra-institutional cultural concerns. Rather than contend with these concerns and their impact on students, many HSIs label them as deficient or underprepared. Isabel Araiza, Humberto Cárdenas Jr., and Susan Loudermilk Garza ponder whether faculty teaching HSI writing and literacy-based courses depend on this prevailing discourse concerning Latinx students at these institutions, which “employs an ‘at-risk’ tone, so faculty may have nothing to shape their perceptions but this negative discourse” (88). The study by Araiza et al. illustrates that institutions, department-level administrators, and faculty need research to avoid making assumptions about students’ linguistic literacies. This small change can make significant progress toward shifting away from accomodationist interest convergence models at HSIs.

Steve Lamos demonstrates the work of interest convergence and divergence in the development and administration of high risk basic writing programs. The subtle assertion of raciolinguistic dominance, such as advocating for mainstream standards alongside basic writing programs, occurred during instances of interest convergence. Moments of interest divergence, however, were met with more explicit arguments about “upholding excellence” at the cost of recruiting raciolinguistically underrepresented and low-income student populations (Lamos 13-14; see also: Mendenhall). Lamos's study is the foremost example of an interest convergence analysis of race in composition studies currently. Although the interest convergence thesis provides a useful analytical frame for examining institutional efforts at racial equity, legal scholar Justin Driver makes a salient critique that “Even if one accepts the notion that interests can be divvied up by race, the interest-convergence theory offers an overly simplistic view of both the ability to identify and to express what constitutes ‘black interests’ and ‘white interests’” (165). I am not focused on White and Black racial interests that were necessary to explore within the context of Brown v. Board at the time of the theory’s development; I am concerned with the interest convergence attitudes at HSIs that impact writing program administrators’ (WPAs’) preservation of institutional raciolinguistic cultural interests and subjugation of raciolingustic cultural interests honored and put into practice by many students from Latinx cultures at HSIs.

An Interest Convergence Case Study: Methodology

For the purposes of this analysis, I am specifically attentive to the literacy-based cultural interests of both the institution and students' home or heritage raciolinguistic communities. The intersecting institutional critique and racial methodology scaffold the interest convergence analysis of how ethnic-racial cultural interests of the institutions and Latinx student cultures converge and diverge. Using this methodological lens, the study highlights where sociocultural racial interests shape the servingness of institutions.

The foundations of social engagement in our society traditionally derive from culturally White discursive manifestations discussed in the previous section, and higher education institutions act as sentries of these manifestations (Smitherman; Kynard “Writing”; Kareem; Inoue; Perryman-Clark; Martinez). Briefly, cultural whiteness exhibits through rhetorical discourse as socially and culturally detached, hyperindividualist methods and claims of rational, controlled objectivity. Academic texts should appear unimpeded by their community, culture, or external factors. The local cultural contexts and interests of Latinx communities vary greatly (Araiza et al.; Barajas; Davila and Elder; Excelencia in Education), although their shared histories and evolution have led to some shared values and customs.

I look at writing programs and writing program administrators, specifically, because they are in an interest converging position that holds the expectation of serving institutional and student raciolinguistic cultural interests, but lack of professional development, knowledge of culturally sustaining literacies, or raciolinguistic connection often leads them to overall serving the interests of colleges and universities. My use of the interest convergence dilemma is not about essentializing students; it is about emphasizing convergence and divergence in the rhetorical worldview of the dominant ethnic culture and, in this case, Latinx cultures served at these Floridian institutions in order to illustrate some of the difficulties of writing programs in serving multiple cultural interests. I analyze these interests with an eye on this “pragmatic mechanism for change that extends the power of our field beyond ... the university” (Porter et al. 612-613). At the institution level, this study focused on

HSI-centric professional development efforts,

general education writing emphasis, and

the racial-ethnic cultures of institutional governance

Institutional critique methodologies work to initiate reform, so the focus of this study lies with these units of analysis which provide the most immediate opportunities for intervention that might greatly shape institutional culture. As a critical node of the larger institution, my own writing program can learn how to enrich our servingness of the literacy cultural interests of Latinx students. I examine the interview responses and institutional curricular approaches under an institutional racial methodology to pinpoint how racialized ideologies about Latinx cultures and literacies materialize in the three focus areas. Interest convergence offers an interrogation of where these ideologies result in more and less serving practices.

At the center of the study are two research questions that guided my inquiry into the importance of institutional support of first-year writing programs attempting to serve Latinx writers:

What curricular or professional development practices have you or your university implemented as a result of being designated an HSI?

What challenges do you believe the institution as a whole faces in supporting Latinx, Hispanic, and/or Latin American students?

I gathered the answers for each of these inquiries and their derivatives through survey and conversational interview methods.

Research Methods and Institutional Contexts

The IRB approved the survey and interview research of this study. I interviewed the three writing program administrators on each of their campuses, following their responses to a quantitative survey (Appendix 1) sent electronically. The aim of the survey was to gauge general attitudes about being a writing program at an HSI. The interview questions (Appendix 2) delved deeper into the causes, correlations, and impact of these attitudes on the institutions and departments, as well as the ways racialized ideologies shape policies and practices. In composition studies, quantitative surveys are often used to gauge an overview of individual and institutional behavior and attitudes within specific contexts by “gathering information about a large population by questioning a smaller sample” (Anderson et al. 60), and conversational interviews offer a “circuitous communicative path, with questions opening spaces for discussion [that lead] to elaborations of the same topic or explorations of related ones” (Gilyard and Taylor vii). For the bulk of the analysis that follows, I relied heavily on the interview data, because they afforded us—interviewer and respondent—the occasion for delving into in-depth discussions about the connection of culture, race, language diversity, and class to the work we do every day. I acknowledge that the embedded social dynamics of the interviews possibly influenced the level of comfort and willingness to report in my participants. In addition to my raced-gendered formation and my socioeconomic upbringing, I was a few years to nearly two decades younger than my participants, and had been on the tenure-track in an independent writing department for only a little over two years at a newly minted HSI at the time of the interviews. Through these interview conversations, I perceived a divergence of interests between what culture-centered perspectives (or lack thereof) the institution believed would augment the social-academic student experiences and what culture-centered perspectives students and faculty believed would.

The institutions provide three separate contexts to administrate writing curriculum. One of these, I've designated Private State University or PSU, as it is a privately funded, nonprofit institution of under 8,000 students without a faith association. The WPA (PSU-WPA) here is White American, 31 to 40 years old, with 11-15 years of college-level writing teaching experience. Another of these I've designated Multicultural Coastal University or MCU, because it is a state regional comprehensive university along the coast with a highly multicultural (multiethnic, multilingual, multiracial, and international) student population of nearly 35,000. MCU-WPA is White American, 41 to 50 years of age, with 11-15 years of college-level writing teaching experience. In terms of enrollment numbers, it is also the most similar to my university compared to the other institutions, although MCU enrolls less than half of the students at my university. I refer to the final institution as Faith-based Private University or FPU due to its expression of the values of Catholicism in its mission and vision. The WPA also serves as Chair of the English Department and Dean of the university’s liberal arts and sciences college, identifies as Latino, and is 51-60 years of age with more than 15 years of experience teaching college writing. Nearly 70% of dually enrolled students at FPU identify as “Hispanic.” According to Garcia, “HSIs are more likely to enroll ... underprepared students ... and students with less access to academic, financial, cultural, and social capital” (126S-127S), and dual enrollment experiences can contribute to traditional college preparedness while also aligning with students’ cultural interests.

I offer the following case study to detail these administrators’ perceptions of institutional willingness to converge institutionalized raciolinguistic and literacy cultural interests with those of Latinx students.

Institution-Student Interest Convergence in Three Floridian HSI Writing Programs

Multicultural Coastal University

“I know that when we were on the threshold of getting that designation, you know we’d heard about it, we’d heard that the administration was happy about that designation, but it doesn’t seem to have impacted the goals of the university in any way, it’s not part of the conversation that I hear.”

WPA, MCU

Professional Development. The institutional cultural interests at MCU are strongly linked to its objective to meet particular metrics, according to the WPA. The institutional organizational identity and emphasis on its own cultural interests at MCU place it in the strictly Latinx-enrolling quadrant of Garcia's matrix and on the institutional culture side of interest convergence. The institution presents low on both kinds of outcomes in Garcia’s typology. Before our conversation about their program, MCU-WPA noted on their preliminary survey response that their institution had implemented no services or practices as a result of its HSI designation. Keep in mind that, just as with the university where I teach, MCU received its HSI label within the last five years. The survey permitted respondents to describe additional services that I may not have included, and MCU-WPA offered nothing here either. When it comes to professional development targeted at the HSI institutional context, MCU-WPA mentioned during our interview that “in terms of pedagogy and serving students, I don’t know if we think we’re already doing [professional development] but there’s nothing really, there’s not a lot faculty development around teaching at all.” The survey responses noted that, institutionally, the WPA is unaware of any targeted retention efforts for Latinx populations, HSI task force (like the ones created at my university as we moved toward becoming an HSI), or alterations to general education curriculum. According to Garcia’s HSI organizational typology, institutions that are Latinx-enrolling are “constructed by members to mean that the institution simply enrolls a minimum of 25% Latinx students but does not produce an equitable number of legitimized outcomes for Latinx students and does not have an organizational culture for supporting Latinxs on campus” (121S). MCU’s high number of Latinx- or Hispanic-identifying students but low efforts at practices and procedures accounting for the experiences of these students illustrates its lack of cultural support.

As a result of MCU’s cultural interests remaining focused on traditional, primarily Eurocentric-validated outcomes such as “graduation rates, enrollment in advanced degree programs, and employment” with legitimacy tied to “policies and procedures that are enforced by government, public opinion, law, courts, and [other] external criteria” (Garcia 126S), its FYW program reflects dominant racial and ethnic cultural interests. Just because these measures of success are rooted in Eurocentric epistemologies does not indicate irrelevance to BIPOC learning communities; still HSIs and their writing programs or FYW course administrators should evaluate how their conventional, “legitimized” approaches to meet such outcomes actually align with the cultural interests of Latinx student communities overall. Professional development focused on pedagogy, assessment practices, and classroom socialization can begin to address these factors at a programmatic level. MCU-WPA agrees that Latinx-enhancing and Latinx-serving professional development is absent from their program and not encouraged from the institutional culture. For example, they admit, “We could definitely be doing more with ESL [English as a second language] training, right? And just practices. I mean we address sort of language diversity in my orientation, but the training we offer is also very limited.”

Perhaps like many WPAs at similar institutions, MCU’s indicates an almost powerless feeling when explaining the challenges of the institutional culture in serving the HSI student community. MCU-WPA addresses the ways that racial interest divergence creates a lack of Latinx-serving professional development: “To be any kind of minority serving institution, we have to have policies that are more supportive of at-risk students. And our policies are pretty hostile to at-risk students, and I see that as a product of state metrics.” If true, this approach is multiply unfortunate. Not only can it impact students’ access, retention, and success at the university but also faculty preparation and perspectives about what it means to serve in the teaching of writing at an HSI. Although MCU-WPA responded on the preliminary survey that the faculty in the university’s writing program have a positive attitude about its HSI status and are “very willing” to make Latinx-serving curricular, pedagogical, or instructional revisions, they also indicated that faculty wishing to move away from a monolinguist pedagogy lack the institutional support to do so.

General Education Writing. If culturally White literacy interests include cultural and linguistic colonization, universalism, and formalism, MCU certainly represents them in their Gen Ed writing curriculum. The written communication foundations emphasize control, coherence, and correctness. The curriculum statement advised that the purpose of writing is “to develop and organize our thoughts and ideas in intelligible and meaningful ways” and to provide “the examination of evidence, the development of ideas, and the clear expression of those ideas.” In contrast, the university also situates writing as a tool of expression and curiosity claiming that its writing courses encourage students to interrogate common thinking and develop original perceptions of themselves and the world.

This description of the curriculum can seem inspirational towards goals of inclusion and equity in the curriculum, and it is certainly interest convergent, suggesting that the epistemological status quo is not inherently correct. However, the learning expectations of that curriculum state that students will fulfill the requirements of written communication when they

demonstrate effective written communication skills by exhibiting the control of rhetorical elements that include clarity, coherence, comprehensiveness, and mechanical correctness,

analyze, interpret and evaluate information to formulate critical conclusions and arguments, and

identify and apply standards of academic integrity (“Intellectual Foundations Program”).

Instructors certainly have flexibility in choosing how to adapt these outcomes to their courses, but the institution is establishing values about literacy and writing practices meant to proliferate the rhetorical means of Euro-Westernism. The expression of “control of rhetorical elements” looks differently across individuals let alone across varied literacy traditions and linguisticcultures. Even demonstrations of coherence and mechanical correctness can vary from culture to culture and community to community. For example, rhetorical traditions developed through Latinx and Latin American cultures sometimes see elaborative sentence structures and indirection as means of creating coherence; in Euro-Western-based rhetorical conceptions, these practices equate to incoherence in most cases. Even though these communication standards are presumed to be useful for all students, by not acknowledging their cultural context, the institution remains securely invested in its own Eurocentric epistemological interests.

Private State University

Professional Development. PSU-WPA expressed ignorance about the meaning of Hispanic-serving, which may be attributed to a lack of appropriate professional development to better support faculty in teaching and advising capacities. This WPA described the meaning of HSI as referring to “our students who come from Spanish-speaking background.” Their unfamiliarity mirrors MCU-WPA’s. They discussed that the program, department, and university struggle with supporting academically and financially underprepared students, both aspects that national research and policy analysis organization Excelencia in Education claims are key to supporting the HSI student population. One way that the institution supports HSI-based professional development is through encouraging faculty to apply for grants that specifically fund research activities at HSIs. PSU-WPA and I had a conversation about ignorance regarding the institution-level professional development practices for HSI teaching and administrating:

PSU-WPA: So I know I was saying I don't know a lot of institution-wide things, but that doesn't mean there isn't any.

I was thinking like after I did your survey, I learned more about this grant that our STEM faculty has been applying for, for HSI. They’re doing like a big major grant they’re trying to apply for. And I actually joined—part of the grant was a discussion group. It’s on inclusive learning, but it’s a grant that’s tied to HSI for STEM students. And like our whole [goal with] their ideas to bring inclusive learning practices like critical pedagogy practices into science, technology, engineering, and math classrooms, and that sort of thing.

This advocacy from the institution implies a more Latinx-enhancing organizational identity, as it “enroll[s] a minimum 25% Latinx students and enact[s] a culture that enhances the educational experience of Latinx students but [without] producing an equitable number of outcomes for Latinx students” (Garcia 121S). PSU-WPA and I did not discuss outcomes during our conversation, because they do not play a part in this narrative of serving.

PSU-WPA believes the FYW program serves its Latinx students with inclusive pedagogy supported by professionally developing faculty to integrate multilingualism into the curriculum. Obviously, not all Latinx students identify as multilingual; however, enough do to increase efforts to help faculty understand the complexities of different kinds of multilingualism. Ideologically, this emphasis of professional development around curriculum and assessment is most similar to the practices of my own FYW program of all the programs in this study. We continue to develop faculty theoretical knowledge and hands-on experience of critical language awareness, including the correlation between perceptions of race and ethnicity, language, literacy, and intelligence. By comparison, the means for applying this student-focused practice at PSU seems less systemic than our approach. As PSU-WPA notes, “We bring in multilingualism a lot into our curriculum, we encourage our faculty to do the same when they are thinking about readings and assignments,” but also admits, “I feel like when I think about Hispanic I really, I focus on the language itself, and not thinking about the culture, which is this huge oversight on my part.” This view may impact the piecemeal style of incorporating multilingualism. Unlike MCU, though, the PSU FYW program has attempted at least one effort to make multilingual education more intrinsic to its curriculum and pedagogy. “Initially, when my colleague was hired she was hired to be the coordinator of multilingual pedagogies,” PSU-WPA told me, “which the idea was that she would help faculty think about teaching writing and embracing multilingualism or thinking about multilingualism.” Beyond this, the professional development focus on serving Hispanic or Latinx students was not apparent to PSU-WPA at the time of our interview.

General Education Writing. Similar to many institutions—Hispanic-serving or otherwise—PSU’s institutional mission and core commitments contradict their outcomes for writing and literacy. The institutions mission focuses on the Catholic intellectual tradition, which aims for reflection, truth, and informed action leading to social justice and service. These are supported by its core commitments emphasizing inclusion in addition to the aforementioned values. Yet with all of this emphasis on inclusion, collaboration, and service, the expected outcomes for written communication adhere to standard language ideologies. For instance, the institution claims to bestow students with the capacity to take their knowledge beyond to constraints of the classroom, even as its written communication learning outcomes want them to exemplify usage of standard English.

Other Eurocentric epistemological perspectives (Kareem) expected of students include ambiguous notions of organized writing and appropriate evaluation of secondary and primary sources. As I’ve written about previously in drawing on the work of Collins, Eurocentric epistemological perspectives are commonly accepted as valid ways of knowing and applying knowledge without question, even among ostensibly inclusive or antiracist curriculum. Diverse perspectives are a key emphasis of the university's quality enhancement plan, and inclusion along with social justice are central to its mission, yet notions of linguistic justice or even critical language awareness—absolute requirements of truly Latinx-serving institutions—remain absent from its pedagogical framework. PSU suggests that in their first-year writing courses, students will learn

To demonstrate effective critical thinking skills and clear, precise, well-organized writing which demonstrates standard English usage.

To demonstrate competence in the research process by differentiating between primary and secondary sources and appropriately evaluating and incorporating source materials into written assignments (College of Arts and Sciences Learning Goals).

These learning outcomes, while rather conventional of typical college literacy curriculum, fail to do the work of “providing culturally relevant curricula and pedagogy ... for students who have been historically excluded in textbooks, assignments, or classroom discussions” (Garcia 127S). An outcome such as “To exhibit effective critical thinking about delivery, language choices, audience, genre, medium, and author credibility in the correct usage of the author’s chosen dialect or expression pattern” can invite students to think about all writing and language use creatively in ways that sustain their cultural and personal linguistic profiles. However, such an omission from the current outcomes directly counters the university’s honoring of its Dominican heritage and valuing of multiple layers of diversity and inclusion.

The FYW program at PSU attempts to pursue this inclusive ideology by integrating a community-based research project in its second FYW course. The project, which includes an “interview [with] someone about their literacy practices—someone who is sort of representative of some community that the student knows about or the student is a member of” is the most numerically significant assignment of the course, indicating its importance to student learning outcomes (PSU-WPA). On the assignment sheet, students are presented with ethnolinguistic communities as one example for the project. Depending on how this project is applied throughout the program by individual instructors, it might help to place the FYW program squarely in the center of the interest convergence model as well as on the serving/enhancing axes of Garcia's HSI typology. It has the potential to honor the community-belonging culture of many Latinx communities yet only to the extent that it still represents the academic research culture of the institution.

Garcia shows that students believe that institutions—and I would add FYW programs—which hold truly Latinx-serving identities are certain to integrate Latinx-centric events into the institutional culture (126S). Therefore, this is one element on the student cultural interests side of the interest convergence model. Similarly, Deborah Santiago (2017 What) demonstrates that one tool that works for Latinx students in higher education is culturally and linguistically relevant curricular and extracurricular activities. One example of a program that employs this tool collaboratively is the Center for English Language Acquisition and Culture at Saint Peter’s University, where program participants “are required to take the first year writing courses at CELAC to give students a cocoon where they can grow during their first year of college” and enter “workshop contests ... where students utilize ‘translanguaging’ to relate their identities and/or journeys to the U.S.” (19). This approach honors and draws on the participants' border or meshed cultures. At PSU, however, PSU-WPA says that “we have a hard time getting support for these kind of [programs and events] from our students!”

Part of the obstacle to getting more Latinx-centric systemic implementations could be that “I don't know if, as an institution, if we think about it in terms of culture, if we think about it in terms of family background or nationality.” This kind of thinking is common for many English first-language speakers, because our interpretations of language practice are segregated from our interpretations of cultural identity. In this way, the FYW program leans more alongside the institutional culture, as PSU-WPA notes even though “there are ways that our university does sort of acknowledge the cultural richness of our Hispanic students,” faculty aren't always encouraged to think about it culturally.

Faith-based Private University

Professional Development. FPU-WPA’s intersectional professional and ethnic identity is one factor that might influence their connection to both students and the institution. This combination of cultural identity and institutional experience helps FPU-WPA apply the institutional curriculum for writing in specific culturally relevant ways. Even as the WPA makes these efforts, institutionally by the standards of Garcia’s typology, FPU enhances Latinx students’ cultural connections the least and produces the least of these students meeting the institutional learning outcomes. As is the case with PSU, the professional development around FPU's writing curriculum, which is held within its introductory college English courses, encompasses more considerations of Latinx-relevant student cultural interests than the institutional professional development efforts. From our conversation, FPU-WPA indicated that the institution intends to be Latinx-serving—high traditional institutional outcomes for Latinxs and high organizational reflection of Latinx culture—but becomes either disparately Latinx-producing with high traditional outcomes or Latinx-enhancing with high cultural reflection. The HSI-specific professional development efforts at the institutional level are focused on curriculum without real faculty development in culturally sustaining or culturally relevant teaching. For instance, FPU-WPA describes a collapsed institution-level program which requires faculty to “take either a Catholic identity or diversity course before they’re allowed to designate one of their classes as [diversity-focused] or [Catholic-identity-focused].” Inclusion-centric professional development such as this seems to support student cultural interests, and to an extent, they do. They show a recognition of student experiences beyond the status quo. However, the central objective may be to give the optics of inclusive and equitable curriculum, without the substantive professional development practices to hold that curriculum in place long-term.

General Education Writing. The general education requirements at FPU extend from its mission to encourage lifelong education centered on Catholic-centric values and morals. The humanities general education curriculum across the university claims that students will cultivate “college-level written communication” skills, according to the institution’s undergraduate catalog. These written communication skills, one part of the English department first-year writing course literacies, are evaluated against the “general education competencies” for “written English.” Students are evaluated as competent in written communication once they show that they can:

demonstrate proficiency when writing shorter essays for specific audiences;

recognize and employ grammatical and syntactical structures in the appropriate context; and

integrate critical reading skills with the writing process, including the completion of research papers that incorporate scholarly source materials from the University library and its databases (“General Education Requirements”).

These competencies are representative of typical institutional cultural interests but may make space for ethnolinguistic cultural interests, based on an instructor's translation of the competencies to learning outcomes. For Garcia and Otgonjargal Okhidoi, because historically, Latinx voices have been overall silent in U.S. college general education curriculum, institutions claiming to serve Latinx communities should assess how these cultures are represented across the curriculum, including in discourse-based subjects. FPU's institution-wide professional development practices also miss the mark in supporting faculty in implementing culturally relevant curricula. According to FPU-WPA, “You see it all the time especially when faculty are complaining about like ‘these kids can’t write papers, these kids write terribly—look at this kid how badly he spelled this word.’ I mean that’s an academic attitude that just really ostracizes a portion of the population.” Curriculum that critically immerses all students in the histories and contemporary lifestyles of Latinx communities is fundamental to institutions that serve rather than simply enroll Latinx students (Garcia).

While FPU consists of the highest number Latinx students of the three schools discussed in this study, its writing competencies are based in Eurocentric epistemological standards. The ideological gap between the institution’s mission of inclusivity and the academic culture of Euro-Western standards is reflected in the previously discussed attitudes of FPU-WPA's colleagues. Garcia urges “administrators ... to engage institutional members in deep conversations about how the mission, values, and priorities connect to the culture, curriculum, and practices of the institution” (128S). The FPU institutional mission of inviting cultural and international diversity is stunted by its learning objectives in this area.

Racial-Ethnic Cultures of Institutional Governance

If the interest convergence theory postulates that those stakeholders with culturally White racial interests will strive to maintain those racial cultural interests, even in efforts to achieve racial justice, maintaining culturally White administration, with culturally White trustees and advisors will always sustain culturally White institutional interests, unless concerted efforts are made to do otherwise. The culturally Eurocentric organizational identity of the university’s administration and governance has great influence on its raciolinguistic cultural value system. Tom Olson demonstrates the presence of intersectional bias that does take place in college boardroom, bias that is often partially, although not fully, based on racial formation. With no Latinx-presenting executives in the top levels of university administration at MCU, two non-Latinx BIPOC Board of Trustees members, and but one Latina dean of one of the institution’s academic colleges, this leadership perhaps lacks the consciousness, or maybe the impetus, needed to understand how to serve Latinx students beyond culturally White orientations.

PSU presents a similar institutional leadership scenario, with BIPOC identities represented in two of eight members in the university’s upper echelon of administration from underrepresented racial communities. Neither appear to be from Latinx cultures in the Americas or the Caribbean.{2} Of the five officers of the board of trustees, one officer is non-Latinx BIPOC, and of the seven university college deans, just one is also BIPOC and Latinx. Of all of these administrative bodies, but one presumably comes from a culturally Latinx community. Institutions like PSU that claim to value and represent global, cultural, and scholastic inclusion must wrestle with the uncomfortable question of how they can receive truly culturally relevant guidance on serving the raciolinguistic cultural interests of Latinx communities if those in institutional authority—those in charge of that advice—primarily have little experience with the cultural customs and values of those communities.

Although FPU-WPA as the chair of academic programs in the college of liberal arts and social sciences identifies as Latino, the racial-ethnic makeup of university administration and the advisory board is predominantly White American. Comparable to MCU and PSU, and most higher education institutions in the U.S., FPU is governed by administrators who come from this dominant racial culture. FPU-WPA suggests ways that the outcomes of this cultural gap impacts the student experience. This department chair identifies the disconnect between “pushing the idea that we are trying to get first generation college students, and we’re trying to get students that have been pretty much disenfranchised from the university experience” and “that [those same students] also have to do this completely by themselves” even as that viewpoint “completely runs counter to the way that we understand that family operates in that culture.” According to FPU-WPA, the university boasts no supports services that attend to these particular cultural interests, especially for early college students. As Olson illustrates, a closer look at the boardrooms of higher education reveals “the intersection of ethnicity, race, class, and unwritten but ingrained university policy” (3). The racial and ethnic cultural identities of those in authority at HSIs is far from the only facet affecting ethnic-racial cultural inclusion and representation in the curriculum or support services at these institutions, but they can be a component. A follow-up to this pilot study might include gathering more data about the language attitudes and ideologies of individual board members.

Implications for Teaching Writing: From Interest Convergence to Cultural Sustainability at HSIs

HSIs hold a unique position that is critical to the rapidly evolving culture of U.S. higher education. The majority of HSIs are two-year institutions. Some of these have transformed into free- or reduced-tuition institutions, meaning institutional and legislative decisions concerning these measures impact the college-aged Latinx population more closely than many other demographics. In enrolling and graduating the fastest expanding student population in the nation, they have an enormous impact on the future of critical professions and civic society. HSIs focused on enrollment deny a large segment of the student body the culturally conscious resources to prepare for their academic, career, and life goals the same way that students who fit the institutional racial and linguistic status quo have the opportunity to do. Resistance to institutional policies and practices that connect to and sustain Latinx cultures keep these institutions from moving beyond converging interests to align with their own cultural benefit. It keeps them from holding a truly Hispanic-serving identity. As long as these institutions follow in the vein of the case studies described here and primarily focus on metrics-driven outcomes legitimized by institutions, “including graduation rates, enrollment in advanced degree programs, and employment” (Garcia 126S), they will do little to truly support writing programs that serve Latinx writers. Garcia explains that “predominantly White institutions have normalized these outcomes while racialized institutions are forced to emulate them” (126S). From an interest convergence perspective, there is little cultural incentive for institutions to shift their ideologies regarding institutionalized outcomes. HSIs, like most U.S. universities and colleges, compete for funding, student admissions, and stakeholder investments based on these current measures of “institutional excellence” (Lamos 151), and particularly in working student writers, this can be antithetical to supportive pedagogical and curricular practices. Although one part of a true serving institutional identity is to drive student success in these touchstones, the complementary part is to provide an institutional “culture that effectively serves Latinxs” (Garcia 127S). Examples include “opportunities to engage with the Latinx community, a campus climate that is positive for Latinx students, and the establishment of support programs for Latinx students” (Garcia 127S). Lamos suggests that the higher education industry pursuit of so-called standards of excellence has driven interest divergence in areas such as basic writing programs (151), which, as Garcia finds, often support students from Latinx communities (127S).

This interest convergence analysis illustrates that ethnic-racial and linguistic cultural interests of the institution do not diverge from those of students’ cultures, necessarily, but they converge to privilege the culturally White institutional perspectives. These perspectives constrict the work of writing programs and writing faculty by restricting curriculum and professional development to practices that serve the institution and its stakeholders. Each institution’s general education writing curriculum keeps the literacy gates, and WPAs are called upon to act as keepers at the gates. Regarding curricular revisions, current Gen Ed writing emphasis ultimately reflects literacy education ideologies that uphold cultural whiteness. Regardless of the experience or approach of the WPA, the lack of institutional support in developing and teaching culturally sustaining curricula, an approach that maintains cultural perspectives and practices in different aspects of the curriculum, results in limited cultural interest convergence. This limitation emerges, as well, through the professional development strategies, which all respondents noted included little to no attention to serving Latinx students or families. If these institutions want to be earnest in their serving attributes as HSIs, WPAs should receive culturally informed professional development opportunities that prioritize more than language difference. These initiatives might help faculty and TAs understand ways to work with close familial involvement and community connection. Remember, it is all about belonging. The work of HSI WPAs necessitates these shifts toward culturally sustaining institutional identities that transcend interest convergence. With this, they can increase their efforts to reform writing programs that meet institutional outcomes and enhance cultural belonging.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Preliminary Survey

Demographics

Please select your age range:

21-30

31-40

41-50

51-60

Which race or ethnicity do you identify with most closely?

Black/African descent (with or without Latinx/Hispanic)

Latinx/Chicanx/Mestizx/Central American

Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander

Native American/American Indian/Indigenous American/First Nations

White/European descent/Anglo (without Latinx/Hispanic)

Multi-racial or-ethnic

Background

Which of the following best describes your faculty title?

-

Full-Time Instructor

Full-Time Lecturer

Adjunct Instructor/Lecturer

Assistant Professor

Associate Professor

Full Professor

Visiting Assistant Professor

Other (please specify)

Which of the following best describes your administrative title?

Department Chair

Director of Composition

Director of First-Year Writing

Writing Across the Curriculum Director

Academic Affairs Dean/Academic Affairs Associate Dean

Other (please specify)

On average, how many courses do you teach per academic year (including summer terms)?

0

1-3

4-6

7-9

More than 9

How long have been teaching writing?

0-3 years

4-6 years

7-10 years

11-15 years

More than 15 years

How long have you served as an administrator of writing curriculum, courses, or teaching?

-

0-3 years

4-6 years

7-10 years

11-15 years

More than 15 years

Institution Practices

Prior to being invited to participate in this study were you aware that your university or college is an HSI?

Yes

No

Which of the following (if any) services or practices has your college or university implemented as a result of its HSI designation?

Alterations to Gen Ed curriculum

Creation of HSI task force

Peer-to-peer mentoring targeted to Latinx/Hispanic populations

Regular family-oriented events

Targeted retention efforts for Latinx/Hispanic populations

Intensive Language Institute

None of the above

Other (please specify)

Department or Program Practices

Which of the following best describes the overall attitudes of faculty in your department or writing program towards being an HSI?

Unaware

Positive

Negative

Confused

Other (please specify)

Which of the following best describes the faculty willingness in your department or writing program to make curricular, pedagogical, or instructional changes to better serve the HSI population?

Very willing

Somewhat willing

Unsure

Somewhat unwilling

Completely unwilling

In your estimation, which of the following best describes the faculty language attitudes towards students in your department or writing program?

Prefers monolingualism in the classroom and in assignments

Accepts but does not encourage switching between English and Spanish or other languages in the classroom but not in assignments

Encourages switching between English and Spanish or other languages in the classroom but not in assignments

Encourages meshing English and Spanish or other languages in the classroom and in assignments

Prefers to move away from monolingualism but unsure of how without support. Other (please describe)

You may be contacted to participate in a face-to-face interview within two weeks of completing the survey. If you have questions or concerns regarding this survey, or you would like to withdraw from the study, please send an e-mail to [Author’s email address].

Appendix 2: Semi-structured Interview Questions*

What does the term Hispanic-serving institution mean to you?

What efforts has your institution made to help you and other faculty understand some of the nuances of Hispanic or Latinx cultures? (e.g. family inclusion and involvement, community connections, respect for elders’ wisdom, etc.)

What professional development activities or efforts have been put in place to help faculty work with the HSI population?

What challenges do you believe the institution as a whole faces in supporting Latinx, Hispanic, and/or Latin American students?

What is the central philosophy of your writing curriculum?

How do you think that philosophy promotes or hinders working with teaching and learning practices at this HSI?

Describe what you see as critical to designing, revising, or managing writing curriculum at your HSI.

What changes, revisions, or additions did you make to your own administration or teaching of writing courses upon obtaining HSI status?

*Other questions developed from emerging conversations

Notes

-

The work of sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva defines four frames for race-evasive (colorblind) racist ideology: “abstract liberalism, naturalization of race, cultural racism, and minimization of racism” (26). (Return to text.)

-

From the photographs available on the university’s website, the women-presenting administrators appear to be Black African-descendant. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Alemán, Enrique, Jr. and Sonya M. Alemán. ‘Do Latin@ Interests Always have to Converge with White Interests?’: (Re)claiming Racial Realism and Interest-Convergence in Critical Race Theory Praxis. Race, Ethnicity and Education, vol. 13, no. 1, 2010, pp. 1-21, https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320903549644.

Anderson, Daniel, et al. Integrating Multimodality into Composition Curricula: Survey Methodology and Results from a CCCC Research Grant. Composition Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2006, pp. 59-84.

Araiza, Isabel, et al. Literate Practices/Language Practices: What Do We Really Know about Our Students? Teaching Writing with Latino/a Students: Lessons Learned at Hispanic-Serving Institutions, edited by Cristina Kirklighter et al., SUNY Press, 2007, pp. 87-97.

Artze-Vega, Isis, et al. Más allá del inglés: A Bilingual Approach to College Composition. Teaching Writing with Latino/a Students: Lessons Learned at Hispanic-Serving Institutions, edited by Cristina Kirklighter et al., SUNY Press, 2007, 99-117.

Barajas, E. Domínguez. Crafting a Composition Pedagogy with Latino Students in Mind. Composition Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, 2017, pp. 216-218.

Bell, Derrick. Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest Convergence Dilemma. Harvard Law Review, vol. 93, no. 3, 1980, pp. 518-34.

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. 2nd ed., Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

College of Arts and Sciences Learning Goals. College of Arts and Sciences, 2020. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge, 1991.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, vol. 140, no. 1, 1989, pp. 139-167.

Davila, Bethany, and Cristyn L. Elder. Stretch and Studio Composition Practicum: Creating a Culture of Support and Success for Developing Writers at a Hispanic-Serving Institution. Composition Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, 2017, pp. 167-86.

Delgado, Dolores Bernal. Critical Race Theory, Latino Critical Theory, and Critical Raced-Gendered Epistemologies: Recognizing Students of Color as Holders and Creators of Knowledge. Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 8, no. 1, 2002, pp. 105-126.

Intellectual Foundations Program - General Education Curriculum. Division of Student Affairs, 2023. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020.

Driver, Justin. Rethinking the Interest Convergence Thesis. Northwestern University Law Review, vol. 105, no.1, 2011, pp. 149-197.

Enríquez-Loya, Aydé. Interrogating Ghosts in the Writing Classroom: Decolonial Storytelling Strategies for FYC Bilingual Students. Conference on College Composition and Communication, Portland, OR, 18 March 2017. Lecture.

Excelencia in Education. Programs to Watch: Supporting Young/Innovative Programs. Excelencia in Education, 2018. https://www.edexcelencia.org/2017-programs-watch. Accessed 2 Nov. 2019.

Florida Department of Education. Data & Reports. Florida Department of Education, https://www.fldoe.org/schools/higher-ed/fl-college-system/data-reports/. Accessed 10 January 2022.

Garcia, Gina A. Defined by Outcomes or Culture? Constructing an Organizational Identity for Hispanic-Serving Institutions. American Educational Research Journal, vol. 54, no. 1_suppl, 2017, pp. 111S-134S, doi:10.3102/0002831216669779.

--- and Otgonjargal Okhidoi. Culturally Relevant Practices that Serve Students at a Hispanic Serving Institution. Innovative Higher Education, vol. 40, no. 4, 2015, pp. 345-347.

General Education Requirements. Undergraduate Catalog 2020-2021. Accessed 13 Dec. 2021.

Gilyard, Keith and Victor E. Taylor. Preface. Conversations in Cultural Rhetorics and Composition Studies, by Gilyard and Taylor, The Davies Group Publishers, 2009, pp. vii-xiv.

Inoue, Asao B. Friday Plenary Address: Racism in Writing Programs and the CWPA. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 40, no. 1, 2016, pp.134-154.

Kareem, Jamila. A Critical Race Analysis of Transition Level Writing Curriculum to Support the Racially Diverse Two-Year College. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 271-96.

Kells, Michelle Hall. Writing Across Communities: Deliberation and the Discursive Possibilities of WAC. Reflections: A Journal of Writing, Service-Learning, and Community Literacy, vol. 6, no. 1, 2007, pp. 87-108.

Kirklighter, Cristina, Susan Wolff Murphy, and Diana Cárdenas, editors. Teaching Writing with Latino/a Students: Lessons Learned at Hispanic-Serving Institutions. SUNY Press, 2007.

Kynard, Carmen. Writing While Black: The Colour Line, Black Discourses and Assessment in the Institutionalization of Writing Instruction. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, vol. 7, no. 2, 2008, pp. 4-34.

Lamos, Steve. Interests and Opportunities: Race, Racism, and University Writing Instruction in the Post-civil Rights Era. U Pittsburgh P, 2011.

LatCrit. About LatCrit. LatCrit, 2020. https://latcrit.org/about-latcrit/. Accessed 4 Oct. 2022.

Martinez, Aja Y. ‘The American Way’: Resisting the Empire of Force and Color-Blind Racism. College English, vol. 71, no. 6, 2009, pp. 584-595.

Mendenhall, Annie S. Desegregation State: College Writing Programs After the Civil Rights Movement. Utah State UP, 2022.

Olson, Tom. Racism in the College Boardroom? A Personal Narrative and Case Study. Race and Pedagogy Journal: Teaching and Learning for Justice, vol. 5, no. 3, 2022, https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1102&context=rpj. Accessed 17 Oct. 2022.

Paris, Django, and H. Samy Alim, editors. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. Teachers College P, 2017.

Perryman-Clark, Staci M. Africanized Patterns of Expression: A Case Study of African American Students' Expository Writing Patterns across Written Contexts. Pedagogy, vol. 12 no. 2, 2012, pp. 253-280.

Porter, James, et al. Institutional Critique: A Rhetorical Methodology for Change. College Composition and Communication, vol. 51, no. 4, 2000, pp. 610-642.

Santiago, Deborah A. 2017 What Works for Latino Students in Higher Education. Excelencia in Education, 2017. https://www.edexcelencia.org/research/publications/2017-what-works-latino-students-higher-education. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020.

---. Inventing Hispanic-Serving Institutions: The Basics. Excelencia in Education, 2006. https://www.edexcelencia.org/research/issue-briefs/inventing-hispanic-serving-institutions-basics. Accessed 8 Dec. 2020.

Smitherman, Geneva. Talkin that Talk: Language, Culture and Education in African America. Routledge, 1999.

Solórzano, Daniel G. and Tara J. Yosso. Critical Race and LatCrit Theory and Method: Counter-storytelling. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 14, no. 4, 2001, pp. 471-495. doi: 10.1080/09518390110063365.

Tatum, Beverly. Why are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? Basic Books, 1997.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. ‘Nah, We Straight’: An Argument Against Code Switching. JAC, vol. 29, no. 1/2, 2009, pp. 49-76.

Enrolling or Serving from Composition Forum 51 (Spring 2023)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/51/enrolling.php

© Copyright 2023 Jamila M. Kareem.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 51 table of contents.