Composition Forum 47, Fall 2021

http://compositionforum.com/issue/47/

Mapping a Network: A Posthuman Look at Rhetorical Invention

Abstract: The writing process has helped define students as autonomous writers within the composition classroom. Yet, our writing identities are not stable and shift throughout the writing process. I argue that composition instructors should enhance students’ awareness to their own dynamic, writing subjectivities through a more expansive view of rhetorical invention, using posthumanism as a lens for composition pedagogy. This article presents a pedagogical practice utilizing concept maps and reflective prompts that help students recognize their ecological, writing landscapes. By tracking the human and non-human elements in their writer’s network, students can learn that writers operate within fluid, writing situations that continuously impact their writerly identities.

In the popular academic writing textbook, They Say/I Say, authors Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein note that good academic writing means entering a conversation with others. However, they argue, “despite this growing consensus that writing is a social, conversational act, helping student writers actually participate in these conversations remains a formidable challenge (xvi). The authors suggest that students should become familiar with the rhetorical moves that create a response in a paper, since successful arguments are generally built through some basic rhetorical patterns that most of us use on a daily basis (56). Such a solution may equip the student with the language needed to produce an opinionated sentence, yet the student is still left with the burden to produce an original thought which, as the authors even admit, can “be daunting in academia” (55).

Western academic discourse asks our students to construct rhetorical moves that help develop an individual, assertive “voice,” creating a thesis and eventually an argument that runs throughout the text. The persona carried by the typical western academic within their work is argumentative, relying on debate to produce knowledge while avoiding the value or personal experience or transcendent sources (Bizzell 2). Moreover, knowledge is not immediately available to experience, relying on debate through the careful use of language in order to generate meaning within a classroom (Bizzell 2). The reliance on one’s language to enter and inform a debate is one of many standard characteristics of academic discourse that have helped construct our understanding of the autonomous student writer working through the writing process. Yet a larger web of discursive and non-discursive factors creates the networks we write and debate within, building a more expansive and dynamic writing environment.

Composition and rhetoric scholarship recognizes the fluidity of writer’s subjectivities within this complex network, yet scholars in the field can do more to harness these ideas within their pedagogy, particularly by drawing from Posthuman scholarship in the field. Posthumanists emphasize methods that attempt to situate bodies within their contexts rather than assuming students directly produce texts or knowledge, as if they are part of a Ford production line (Hawk, A Counter-History 180). The struggle for students to find their “voice” may be their attempt to negotiate, or become sensitive to their emerging, writing identities. Students need to locate this notion of betweenness-the space between human and nonhuman-rethinking practice as ecological, particularly when we consider being in relation to a number of technological systems (Boyle 540). I wonder then if the difficulty to master academic writing stems from the inability of composition pedagogy to improve students’ sensitivity to their fluid, writing identities? To find ways to locate themselves within this betweenness?

If we are to take the posthuman subject seriously as writing instructors, then we should examine how a writer’s multiple subjectivities affect and are affected by the writing process while in this space of betweenness. Instructors should advocate for more material influencing pedagogy at the local level that acknowledges the human experience as something that is not simply responding to external factors but emerging from our surroundings (Boyle 551). Rethinking our pedagogical practices in this way requires an updated approach to rhetorical invention and its involvement within process pedagogy. Many composition instructors rely on process pedagogy, and while this has helped bring rhetoric and invention back into composition theory, the practice can become a rigid and simplistic pedagogical model that ignores recent discoveries related to the embodied writer and the complexity of the rhetorical situation. Within these contexts, human subjectivity is emerging through its fluid interactions with other material elements, leading rhetorical theorist to propose the notion of rhetorical ontology, arguing that each rhetorical situation has various human and non-human components that act suasively or agentially (Barnett and Boyle 2). Rhetorical invention should not be taught through a method that ignores the evolving processes of our rhetorical situation but should investigate and attempt to map this process. Specifically, mapping during rhetorical invention can help students trace their networked, writing situations and capture a more fluid picture of the invention process and its relation to their writing selves. In doing so, mapping becomes a way for students to become more sensitive to the complex development of their writing identities.

This article calls for a more thorough engagement between posthumanism and rhetorical invention in the writing process. As it stands, rhetorical invention operating within the writing process only finds the solutions that are already predetermined by the structure established via heuristics or the instructor themselves, and such a model fails to open itself up to evolutionary thinking and subvert the linear process (Hawk, A Counter-History 193-194). I first offer a closer look at posthumanism’s relevance to process pedagogy, noticing how this theory can hopefully inspire more “evolutionary thinking” within process pedagogy. I argue that compositionists can enhance students’ awareness of their own, shifting writing identities by ecologizing the writing process using mapping as a rhetorical heuristic. This awareness can potentially help students navigate the shifting and unpredictable writing environments they find themselves in, growing their sensitives as writers. To illustrate this argument, I’ll be sharing a pedagogical practice I used in my upper-level writing course at William Paterson University. My qualitative analysis covers two sets of student examples from this course.

The Posthuman Subject and the Writing Process

While books like They Say/I Say help students with certain sentence level issues in their writing, they don’t consider the various subjectivities a writer may experience during the writing process or the ecological conditions that help construct these subjectivities. Becoming sensitive to the construction of these subjectivities is a topic of discussion within posthumanism. Katherine Hayles has argued that the “posthuman subject is an amalgam, a collection of heterogeneous components, a material-informational entity whose boundaries undergo continuous construction and reconstruction” (3). According to Andrew Mara and Byron Hawk, posthumanism’s “focus upon the complex interactions of human and nonhuman actors can help researchers avoid either overvaluing the human (humanism) or the nonhuman (antihumanism)” (2). Humans then are seen more as distributed processes rather than discrete identities (Muckelbauer and Hawhee 770). The processes are built through human and nonhuman actors and posthumanist scholars help locate this betweenness among what was previously considered human or nonhuman (Boyle 540). In breaking down these boundaries, posthumanism clears a path for scholars to consider the distributed and often continuous forms of human subjectivity.

The autonomous subject prevailing in academic discourse is questioned when we consider its boundaries undergoing “continuous construction and reconstruction” (Hayles 3). While posthuman arguments within the field have been discussed in the past (see Hawk, Dobrin, and Boyle), posthuman scholarship has provided a “substantial gaze toward subjects and identities, not with much attention to writing” (Dobrin 9). Writing is no longer simply considered an epistemic or social epistemic practice but as a “behavior of intra-acting in the world in which writers participate in their own and the world’s emergence (Cooper 5). Yet process and postprocess theories still heavily rely on humanist assumptions about what writing is and how it is taught (Brooke and Rickert 163). A posthumanist approach to the writing process can help situate a writer’s subjectivity within a larger ecological network, showing our students that the final product is not solely constructed through a metaphysical “I.”

Process Pedagogy

While the process pedagogy movement has been an essential component of composition scholarship, it has been questioned over the years and essentially reframed thanks to the ‘social turn’ starting in the 1980’s. The process movement seemed to discard the complexity of students' writing stages along with the various cultural and social literacy practices brought into the classroom by the students. Indeed, the freedoms proposed to students through process pedagogy made writing seem much easier than it essentially is, presenting a very inaccurate distinction between process and product (Trimbur 109). Process theory leaned heavily on the arguments made by expressivists within the field, romanticizing the writer as lone creator of his or her work (Fraiberg 172). These critiques eventually led to postprocess theory, which claimed that process theory ignored certain outside influences and linguistic constraints, believing that “the writer embodied an uncomplicated subjectivity as he or she sought clear communication through language” (Fraiberg 172).

Much of the difficulty that students can encounter during the writing process is an inability to conceptualize a subjective stance that is less static and more fluid. We cannot abandon process pedagogy wholesale and yet we must acknowledge its limitations, particularly when considering a writer’s subjectivity. As new scholarship within the field begins to doubt the existence of an autonomous subject, what is needed is a conception of the writer that responds to rhetorical urgency and empowers students with a sense of rhetorical awareness within our modern world. Composition pedagogy should allow students to revisit the characterizations they have of themselves as a “student writer” and get them to critically examine these constructs, reinforcing or questioning their writing self within different environments. Students should reflect on their own subjectivity by locating their writing practices within a more dynamic ecological system where the human is one of many components within a larger network that co-constructs a final product. Mapping then can be a way to locate this larger network, pushing students to think outside the rigid boundaries of process pedagogy and consider the posthuman subject where one’s sense of self isn’t static but in constant “construction and reconstruction” (Hayles 3).

Mapping with Ecological Networks in Mind

By positioning rhetorical invention as an ontological activity, a practice that explores the relationship among ecological networks and concepts as assemblages, we can emphasize the exploration of subject complexity in our pedagogical practices. In doing so students can become more rhetorically sensitive to the human and non-human materials that enter their network during the writing process and help shape who they are as writers.

With these ideas in mind, there are certain posthuman-inspired strategies that emphasize mapping techniques while assisting students’ research process. In their textbook Rhetoric: Discovery and Change, Young, Becker, and Pike seek the ontological underpinnings of rhetoric and its relation to the human experience. The authors help students investigate the complex networks of objects within a flat ontology, arguing that objects are a “unit of experience” which are not static and can be seen as part of a larger ecological network (122). Students can trace the mapping of objects within their broader ecological landscape or consider the object itself as an assemblage of various parts, representing a network all within itself. In noting Young, Becker and Pike’s advocacy for object-oriented rhetoric, Rutherford and Palmeri conclude, “such strategies can emphasize the importance of recursively investigating units at multiple levels of scale...encourag[ing] students to resist the stereotypical assumptions they may have about objects (104). They also consider how such strategies can help students develop a “more nuanced and complex understanding of the existence of things in the world” (104). Similar claims are made by compositionists such as Byron Hawk, who argues that pedagogical value for rhetorical invention comes from mapping, not prescribing a given method, and that “the key to mapping out these networks so they can be traversed for invention is that they need to be mapped as they are being traversed, not beforehand” (199). Such strategies not only highlight the spontaneity and networked experience of rhetorical invention, but also help students reimagine their positionality within an environment. Mapping can help students to visualize their place within the world and validate the knowledge they bring with them within the classroom.

Understandably then, the act of mapping to brainstorm a topic should not be seen as a closed off network that is separate from the students’ lived-in experience, and one that simply functions as a fixed part of a linear writing process. The students are a part of the network they map out for themselves and are affected by it. As Latour has noted, “the network does not designate a thing out there that would have roughly the shape of interconnected points, much like a telephone...if qualifies its objectivity, that is, the ability of each actor to make other actors do unexpected things” (129). Students should consider themselves as actors within their ecological network, affecting and being affected in unexpected ways by the very materials they create. The writing process becomes less as a set of sequential stages and more as an ecological web of human and non-human elements.

For example, if students are developing maps in order to brainstorm a topic, they should also track the map’s importance to them as an object that is continuously embedded in their writer’s network, one that moves with them through the writing process. By tracking these connections students can learn that the writing process doesn’t necessarily unfold in a linear sequence and how developing a map can help challenge their presupposed notions of who they are as writers. In the following section, I highlight a pedagogical practice that attempts to ecologize the writing process through a series of mapping techniques and reflection assignments. The practices seek to demonstrate how mapping one’s embedded environment during the writing process can help students build an awareness of their own writing subjectivities.

Classroom Research Context

In the spring of 2018, I conducted research on an upper-level writing course at William Paterson University as a lecturer for the English Department. The course, titled English 1500: Experiences in Literature, operates as both a literature and writing-intensive course. The last writing assignment of the course asked students to develop an argumentative research essay that responded to at least one of the four essays I assigned in class. Each essay was written from a different American author and included Joan Didion, James Baldwin, David Brooks and J.D Vance. All four essays critiqued American idealism from a different perspective. This section of the course was titled Social Critics of America. The students read all four essays and discussed the authors in class, choosing one author to write about. They were then presented with a writing assignment that asked them to respond to one of the essays, developing an argument with the author’s ideas in mind. Students needed to find at least two outside sources to develop their claims.

Alongside classroom lecturers on the texts, I made sure that the group work I provided in the classroom focused on explaining and analyzing specific language inside the essays. I also put the students in groups according to the text they were writing on so that they were among like-minded individuals that could help them shift through the information. However, whether it was Didion’s notions on morality or Baldwin’s musing on the “American Illusion,” I noticed that the concepts and ideas that were being talked about within the classroom were not only complex but also challenging to define without a deeper understanding of the topic. In order to help students think through this complexity, I assigned a concept map for homework. A concept map is a mapping technique that is designed to help students brainstorm ideas while providing them with the freedom to explore and make connections between concepts, removing the anxieties of academic conventions and inspiring spatial learning. I asked students to go home and map out the arguments presented by the author in relation to the two secondary sources they believed they would use in their paper, hoping that a visual representation of these claims could assist in their understanding of the article. Students were asked to create this map through a website entitled MindMup, which provided a free online service for creating concept maps. The website provided creative options for students to design their maps while also allowing them to share their creations by copying and pasting the URL of their maps and posting it on Blackboard. This allowed me to view all the maps from one digital platform and created an opportunity for students to see other student maps.

Once this was completed, the students wrote their first reflection in the next class, asking them to articulate how they felt about creating a map. Was this process useful for you as a reader? How did it help you as a writer? Was this website easy to navigate? I wanted these questions to be broad so that the students could take this reflection in the direction they deemed important, whether it was positive or negative towards the practice. Once they handed in their reflections, they were told to post their concept maps on the discussion board in Blackboard and comment on another student's concept map, providing feedback on layout, organization and meaning of the maps. These comments were articulated on Blackboard for both the student and the instructor to see and enabled students to engage with the materials designed by their peers. In doing so, I hoped that students would not communicate between themselves but also feel open to critique and inspiration without the instructor’s presence, stimulating their minds through an active network of both human and non-human elements. The discussion board was to operate as a network that incorporated student actions over time and provide “the ability of each actor to make other actors do unexpected things” (Latour 129).

Students continued their interactions with both their concept maps and the discussion board on blackboard while working on the first draft of their paper. I purposely emphasized that the map was not a stage that existed before their drafts, but an “element of their environments as a writer” that is constantly helping to shape their writing. In the coming week students were told to revisit their concept map online and expand it based on any new revelations or ideas they discovered as they read through their sources again. During this week students were also encouraged to share their map during class time by presenting it on a Smartboard in class and describing their reasoning behind their map. Students were therefore exposed to their peers’ maps both online and during class time, enabling them to comment in various ways.

In the weeks that followed students worked through two drafts of their paper while having peer review sessions during our class time. During peer review, students were encouraged to share their concept maps and drafts with their peers, reviewing both their final products and the mapping of their process. On the last day of class scheduled for editing this research paper, students created a reverse outline on the drafts they had so far. A reverse outline asks students to read over their drafts and write out one summarizing sentence for each paragraph in their essay. Once completed, students should see a series of sentences that display the organization of their main ideas and how the essay relates to their initial thesis. By having them review their reverse outline, they can get a sense of their paper's organization and whether or not it presents strong support for their overall claim.

Students were then directed to post this outline on the discussion board in Blackboard and describe its relation to their concept map. This would be their second and last reflection assignment. The reflection prompt was as follows:

Now that you’ve completed your reverse outline, what similarities or differences did you notion between your reverse outline and your concept map? Explain. Where did you follow the concept map and when (if you did) move away from the map? Why did you do this? Reflect on the relationship between the map, the comments made on your map by your peers and your draft and describe how they link up or move away from each other.

This question directed the students’ attention back to who they were as writers when completing their concepts maps. This question also reinforced the idea that the concept map was not an earlier component of their writing process but a material element of their embodied writing environment that continuously affects and is affected by them. I wondered if keeping both the concept map and their Blackboard discussions as active, material elements within their writer’s network help showcase a de-stabled, dynamic writing environment. Would it reinforce or make students’ question their initial assumptions of themselves as writers?

Methodology

I followed a grounded theory methodology to approach my research. After collecting the data, I coded both the first reflections after the students completed the concept map and the second reflections they wrote which compared the concept map to their reverse outline. In doing so I noticed four themes that emerged within their reflections:

-

The concept map helped organize my thoughts and provide direction for my essay.

-

The concept map helped me understand the material because I am more of a visual learner.

-

The concept map helped me generate new ideas and push through writer’s block, and.

-

The concept map didn’t help me at all and confused me more.

Two of my English 1500: Experiences of Literature courses went through this series of activities. Below are four student examples that display different approaches to the concept map activity as well as their first and second reflections. I examined when the themes in students’ responses transitioned from their first to their second reflection, locating moments where the student may have changed how they envision themselves as a “student writer.”

Student Responses:

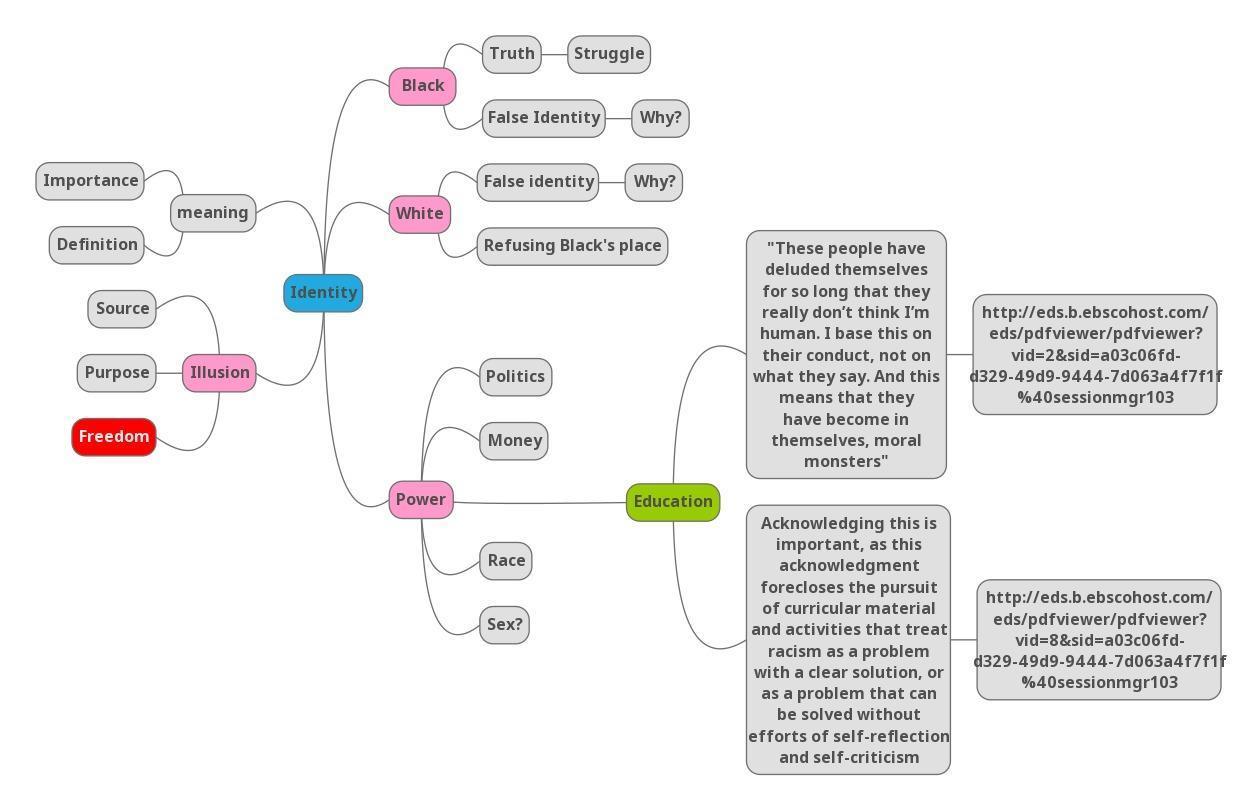

Student A initially used her concept map to break down the themes she saw in James Baldwin’s text, A Letter from the South (see Figure 1). Student A color coded the themes she saw as important within the text such as “Identity,” “Illusion,” “Power,” and “Education.” While most of the themes have branches that entail other abstract concepts, her “education,” node extends into two specific quotes that she then relates to two secondary sources and their links.

Figure 1. Student A’s Concept Map

One could assume that the theme of “education” was something that Student A latched onto in the text, and this seems to correlate with the thesis she finalized in her draft. In her thesis she states, “His book may focus on identity, but the real source of power and ultimately the solution to racism, including shattering the American illusion, is education.” I was curious to read the reflection she wrote after she created her concept map since there seemed to be a strong connection between her map and her thesis statement. Unsurprisingly, Student A noticed the importance the map had to organizing her argument:

The concept map I created really was helpful. Normally I create a written outline on a piece of paper, but when I do that I can’t edit it as easily as I could on the computer. I was literally able to move ideas around with ease. I’m a visual learner so this really helped me see how I could build my argument and the connections between them.

Two things seemed to stand out for me here in Student A’s reflection: the notion that the concept map could help build her argument and create connections and that she describes herself as a “visual learner.” The map seemed to operate as an organizational tool for Student A since it provided her an ability to separate a set of themes and focus on one for her essay. Maps can help subvert the rigid formula of a written outline, allowing the student to view literacy as “spatial and materially constrained” (Gallegos). In displaying a larger network of concepts, Student A can view her argument through a new perspective, moving “ideas around with ease.”

She also initially describes herself as a visual learner here and I wanted to see if this continued as she interacted with the map throughout the writing process. As she engaged in this work, did the writing process affect how she identified herself as a writer? Her second reflection after the essay was finished suggested that not much had changed in her relationship with the map, and it reinforced the type of writer she believed herself to be:

The concept map was helpful for me to try and organize my thoughts. However, I did stray from my original idea. It helped me make my paper more focused and come up with a more specific thesis. I really took one of my concept maps branches and focused on it.... It is easy to still go off track with the concept map as you can just keep adding nodes, but it really helps to visualize the flow of your paper. ... My argument was that education is the focal point of what Baldwin believed. So it was easy to flip my ideas around since I knew all of his supporting points because I mapped them for my old argument.

Student A once again advocates for the map’s ability to help her stay focused and organized within her argument while reinforcing the idea that a map can help her “visualize the flow” of her paper which is important to a visual learner such as herself. Here we see a student coming to terms with who she is as a writer as she encounters other elements within her ecological environment. The moments forged between Student A and the map offer a time for Student A to imagine herself as a particular writer. The map, along with the reflective prompts, helped establish a network of learning tools which enhanced Student A’s ability to locate herself as a visual learner, strengthening this component of her writing identity.

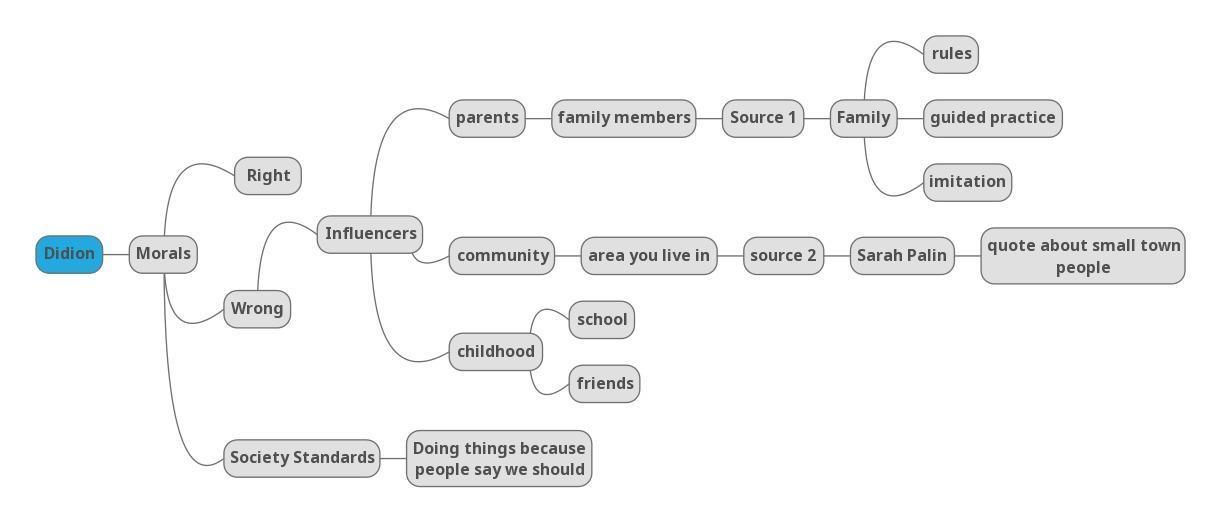

Similar to Student A, Student B’s initial reflection centered on the map's importance to her argument’s organization (see Figure 2). In viewing the map, one can see that Student B attempted to organize her thoughts on Didion’s text, On Morality by considering the various elements that could influence one’s morality such as your parents or your community.

Figure 2. Student B’s Concept Map

This type of organization seemed to help Student B at the beginning stages of her writing process and lead to a thesis statement that argued alongside Didion’s claims on morality, expanding on scientific evidence. In her first reflection Student B noted the map’s ability to help categorize her ideas and operate as a tool that kept her on track. She states, “The concept map definitely helped me organize my essay. I ended up changing my original idea because I realized I couldn’t expand too much...I noticed I kept referring back to it to keep me on track.” Here, we see the student locating the map as an object moving with her through the writing process-a component that continues to affect her choices and keep her “on track.” In her second reflection, Student B describes the importance of the map in a different way, noting how the experience of making the map corroborated her initial feelings towards brainstorming:

I think my map and my essay were very similar because I didn't stray away too much while making the map. I don't over think about what I am going to include. I don't like to go overboard in my thoughts otherwise I become overwhelmed while trying to write my actual essay.

This reflection question did not ask her about her writing process directly, but Student B initiated this discussion anyway, indicating that she is the type of writer who tries not to expand too much during the brainstorming process in order to keep herself from becoming “overwhelmed.” Similar to Student A, Student B saw these reflections as an opportunity to describe who she was as a student writer and learner. By working through the various interactions with the concept map and the reflective prompts on Blackboard, both students reinforced the initial beliefs they had of themselves as writers. It’s within these moments between the writer and the non-human things around them—this betweenness—where writers are finding the space to think through their writerly identities. The experience suggests that interacting with the concept maps didn’t necessarily change who they were as writers, but surprisingly helped remind them of the type of learner or writer they see themselves as. The spontaneity of this networked experience is meant to direct students in various directions, allowing rhetorical invention to evolve and take shape while gaining an awareness of their rhetorical approaches. Indeed, such interactions within their rhetorical contexts attempt to forward a more posthuman practice, where students locate their fluid writing subjects as they emerge alongside (and with the help of) other material elements.

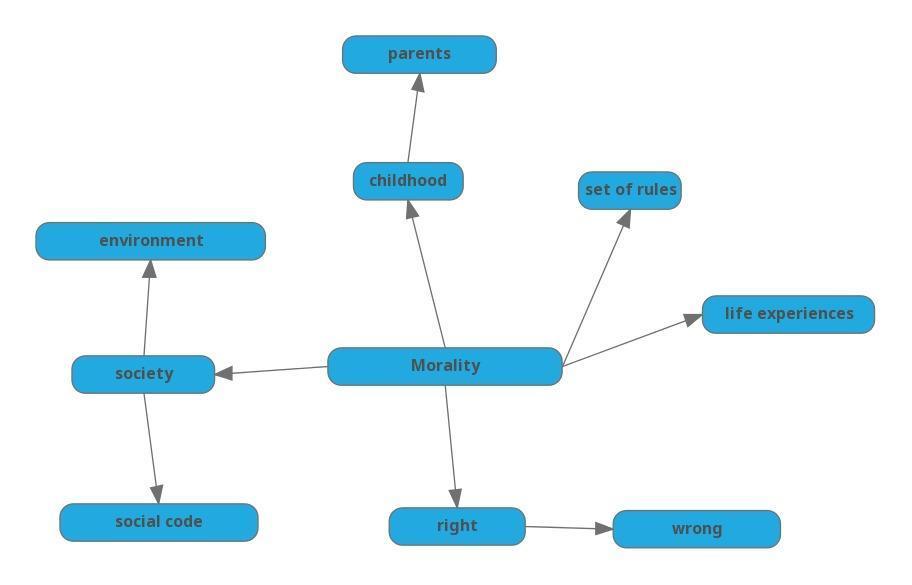

Other students found the process helped them discover new concerns about their writer identities which they did not necessarily have when beginning this brainstorming activity. For example, Student C developed a concept map that was similar to Student B’s since they both considered Joan Didion’s text and its implications on how one views morality (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Student C’s Concept Map

While her map seems rather straightforward, Student C noted in her first reflection that the map was helpful in organizing and developing new ideas. She states, “It helped me organize my thoughts and come up with new topics to talk about.” Student C even commented on Student B’s map on the discussion board, finding a connection between both their approaches to the essay. She notes, “I really like your ideas, I feel that we have a similar approach to this topic. I can totally see where you’re going with this.” On her own initiative, Student C expanded her network by finding a similar map on Blackboard, finding inspiration in Student B’s map that helped corroborate her approach.

In Student C’s second reflection she describes how she will approach the writing process moving forward. Again, this second reflection was assigned after the final draft was complete and after students were told to post their concept maps on Blackboard. Student C states:

At first I tried to use all of my ideas but I saw that it wasn’t working because it wasn’t clear. It sounded like I was jumping from topic to topic and I just wanted to stick with one main idea. Doing the reverse outline and the concept map made me see that now I need to narrow down my ideas so that it flows with my main topic and it doesn’t sound like I’m getting off topic.

For Student C, connecting with her reverse outline and concept map through these reflections helped her find a new approach to her writing process: narrowing down her ideas so that her paper flows and she stays on topic. These connections were built within a more expansive ecological network, where Student C’s writing materials aren’t just moved through chronologically but follow her throughout the writing process. In this web of discursive and non-discursive elements, she has come to a new, more specific conclusion related to her writing self, one that could potentially redefine how she approaches future writing projects. In many ways we are seeing the posthuman subject in action: Student C is more than a disembodied brain working with symbols, but a body that occupies and investigates material situations that are in constant motion (Hawk, Resembling 77).

Reviewing these reflections, I wondered when did Student C come to this newfound conclusion about her writing process? What element or interaction within this network of concept maps, reflections and Blackboard discussions triggered this discovery? Unforeseen encounters—the ones that are sensed without being languaged—can emerge from the writer's web of rough drafts, reflections, and concept maps. These moments of inspiration are hard to locate. However, unlike Student A and B, Student C realized a better rhetorical approach was needed, but all three students seemed to build an awareness of who they were or who they wanted to be as writers.

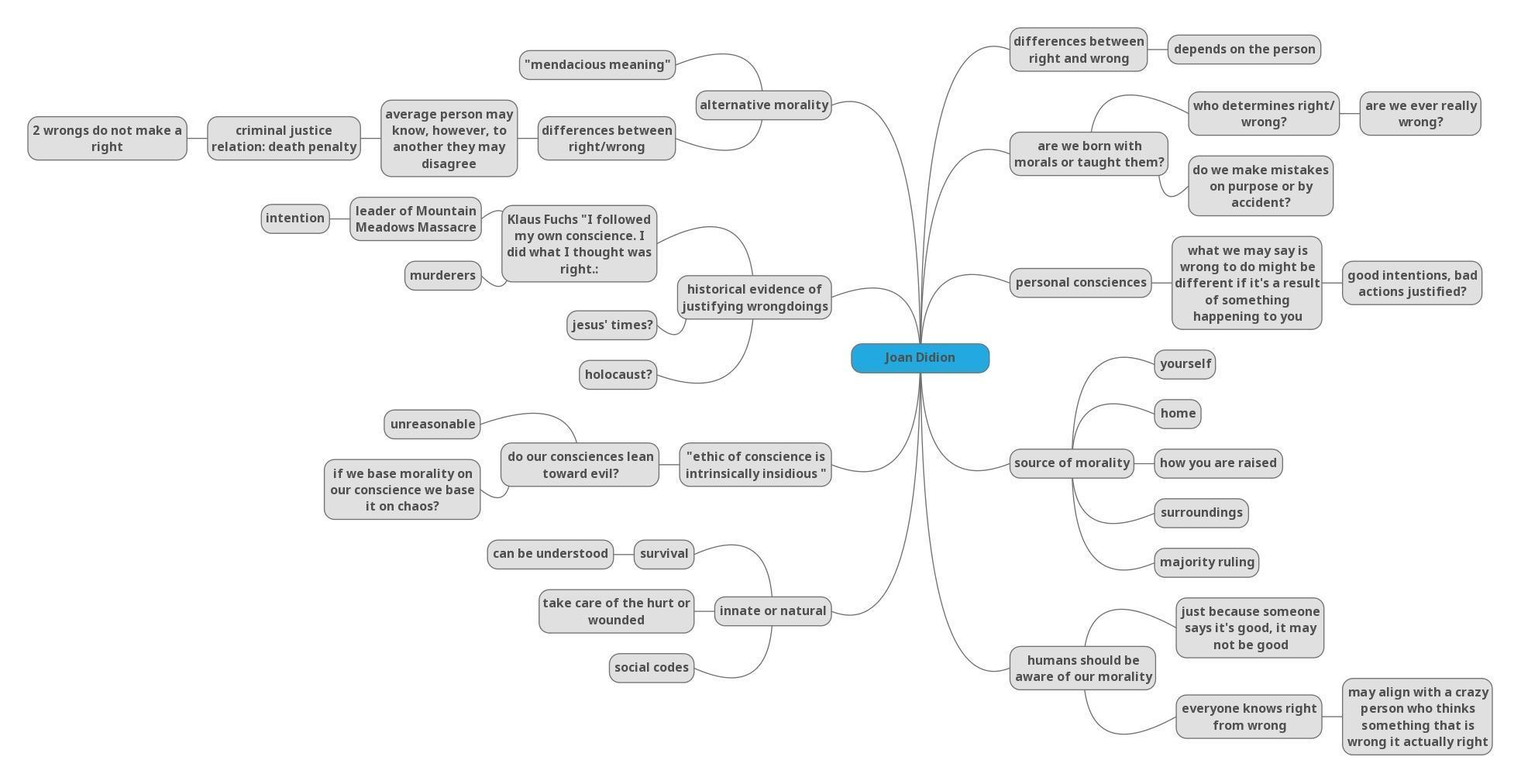

Some students seemed more conflicted with the brainstorming activity, arguing that the concept map brought mixed results to their writing process. Student D designed a very elaborate concept map that included a set of categories and sub-arguments related to Didion’s essay (see Figure 4). The map seemed like a labyrinth of questions and ideas, working within a logic only its creator could understand:

Figure 4. Student D’s Concept Map

I saw this map as an exercise for the student to expel her ideas without concern of paragraph structure, grammar or any other set of constraints usually enforced in academic writing. Student D seemed to have benefited from the freedom and creativity this exercise gave her but did not believe it helped organize her thoughts. As she notes in her first reflection:

I felt like by doing this, it led me into asking myself different questions about my author’s purpose and reasoning. As far as organization goes, it did not help me that much. If anything, it jumbled my thoughts a little bit...Overall I enjoyed doing the map, it was more entertaining and allowed myself to think freely as opposed to always having to have a strict structure before writing

This comment was certainly a departure from the earlier examples mentioned. Unlike most students in the course who saw this exercise mainly as an organizational tool, Student D indicated that the map didn’t help her organize and mentions its ability to help her “think freely” and generate new ideas. Ironically, later in this reflection she mentions this: “seeing all of my ideas, however, spread out, does help me because I will be able to take bits and pieces of my map and elaborate on my ideas.” At first glance I saw this as an indication that the map certainly did help her organize her ideas since she indicates here that a portion of this map will be taken out and elaborated on. In a way, the map located what she would and would not include in her paper, which potentially structured her ideas in an order of usable and non-useable claims to focus on.

My assumptions regarding Student D’s relationship with her concept map were not endorsed by Student D in her first or even her second reflection after the essay was complete. Upon completing the essay, Student D again confirmed that the concept map did not help her organize her paper but indicates that she developed her essay from a particular branch in the map that dealt with historical references:

When making the concept map, my thoughts were all over the place. I had no idea where I wanted to go with this paper, so I just jotted down a bunch of ideas. I ended up taking a piece of my map and running with it in my essay. Looking back, I probably could have focused on different aspects, but I chose an approach based on history. The concept map was not that helpful to me because when I write I like to just let my thoughts flow. I do like being organized, however, when it comes to writing I need it to just come to me.

Like her first reflection, I found Student D’s last reflection to be slightly contradictory in its arguments. She claims (and in fact her paper proves this) that she focused solely on the area of the map that dealt with history, taking a piece of her map and “running with it” as a guidance tool. Her frustration with the map stems from its inability to have a logical process or organization, noting that her “thoughts were all over the place” when making the map and that it’s just a “bunch of ideas.” The assumption here is that such a nonsensical map can’t support the very rational argument she wants to make, yet networks are meant to be messy-what seems illogical can stand/attach/move next to what is deemed logical. The web of connections should work outside this dichotomy, expanding a student’s invention process.

I saw Student D’s map as a visual display of multiple directions she could have taken in her essay, helping her organize the various approaches for this assignment. However, Student D argues that the concept map wasn’t helpful for organization since when she begins a writing assignment she likes to just “let it flow,” and have the ideas “come to me,” an indication that she may choose free writing as her brainstorming tool of choice. Student D may have benefited from the map in some way and failed to fully realize this when reflecting on her own process, however I wasn’t so sure. The mapping may have come too soon in the writing process and actually interfered with her idea generation, complicating the typical structure she’s used to. In connecting and writing with this map throughout her writing process, Student D raised certain points that contradicted the assumptions she has of herself as a writer but I’m not sure if these ideas were fully realized at the end of the assignment. If we are to consider our writer identities fluid and continuous, then it certainly must be hard to locate and label at any given time.

Coincidentally, I approached Student D regarding this internal conflict I saw in her reflections and she acknowledged that she seems to be contradicting herself in these moments and was surprised at this finding. She also agreed that the map did help her organize her essay but overall, she still stuck with her belief that this type of activity wasn’t for her in the future.

Pedagogical Recommendations

Concept maps are naturally useful for students who subscribe to visual learning, enjoy a unique and creative process for rhetorical invention, and appreciate organizational tools for writing assignments. But in this pedagogical practice, I was curious to see how students interacted with these maps as they worked on their drafts and if this interaction reinforced or changed their understanding of themselves as writers. In theory, my practice wanted to embrace rhetorical ontology within the writing process, highlighting how material elements interact suasively and agentially in rhetorical ecologies (Barnett and Boyle 2). Rather than enforcing a more linear, static writing process I wanted to locate the student as posthuman subjects within an ever-evolving ecological landscape that promotes various forms of mediated practices. I did not want students seeing these practices built within a sequence but as activities that develop a network of connections between human and non-human elements, continuously affecting and being affected by us as writers. Some suggestions moving forward:

Instructors Should Utilize Reflective Practices that Help Build Students’ Awareness to their own Fluid Writer Identities

Getting students to consistently reflect on the materials during the writing process was beneficial in redefining the writing process as something that does not have to be a linear, fixed sequence. This also seemed to raise student awareness as writers within a particular rhetorical context, supporting the notion that people who write “develop an identity around writing, one that manifests and is expressed largely through material objects” (Alexis 85). Students were either reinforcing who they believed they were as writers or developing new tools within their writing process as seen in Student C’s example. By having students consistently review and reflect on their connections within this created network they were able to consider whether they were the same, consistent writing subject within a given environment or a new writing subject that desired different writing strategies.

I acknowledge that such reflective practices may counter the very notion that this pedagogy is somehow posthuman in nature. Reflective practices have been described as a humanist practice since it suggests subjects can somehow observe their agency and alter it (Boyle 544). However, I am not requesting students alter their agency but simply dwell in it, which is a different experience than what happens when one explicitly requests an action to be taken after reflection (Lynch 506). The reflections are not meant to be a notational system about one’s position in the world, but a way of engaging and cultivating experience while including the nondiscursive (Lynch 507).

Instructors Should be Sensitive to Students Who Reinforce Who They Are as Writers First

Most students saw the concept map as an object that helped the writer they believed themselves to be. In other words, by reflecting on the map’s assistance during the writing process students tend to stick to the same benefits or drawbacks in each of their reflections. As seen in Student D’s example, students would potentially do this even if their reflections said otherwise. Student D seemed to contradict herself by acknowledging to some degree that the map helped her organize her thoughts and yet continued to argue that it was only helpful in other areas. If the point of this exercise is to heighten students’ awareness of the things that help or hurt them as writers, then instructors should be sensitive to answers like Student D’s. Students like Student D could benefit from a post-assignment conference between themselves and the instructor that gets them to pay closer attention to their own reflections and how it relates to them as students.

Instructors should Facilitate Student’s Critical Thinking

Whether it’s a conference at the end or in the middle of the writing process, instructors should feel comfortable acting as a facilitator to students as they write and look over their own materials. Student D was one of a small set of students I followed up on at the end of this assignment and I wish my presence was more accessible to the students during the process. This could be through enforcing one-on-one meetings or providing more specific questions within their reflections. I’m hesitant on telling students how they should interpret their maps and reflections, but I also want to make sure as an instructor they are reviewing these materials with intention and a sense of owning their work. Therefore, I think instructors should guide students when needed and help cultivate a sense of awareness within students that gets them to locate the contradictions seen within Student D’s example.

Conclusion

Posthumanism calls for more ontological complexity within composition pedagogy and may help students step outside their own ideological constraints and into a more complex network that affects how they conceptualize their writer identities. We need methods that acknowledge rhetoric as “a system that moves and evolves,” and rhetorical heuristics must be read as co-responsible and co-evolutionary, contributing to the forward movement of any becoming (Hawk, “A Counter-History” 194). Rather than seeing writing as a social system in which people act on and make conscious decisions, composition pedagogy needs to place more emphasis on the material and affective ecologies that link to the embodied writer and invent heuristics that develop from these complex ecologies (Hawk, “A Counter-History” 224). During these pedagogical practices, students can learn to question not only how they invent as writers but also whether their assumptions of themselves as writers is always accurate. Our way of considering the autonomous writer may change, but students can still develop more rhetorical awareness through pedagogical models that ecologize the invention process.

Works Cited

Ackerman, John. The Space for Rhetoric in Everyday Life. Towards a Rhetoric of Everyday Life: New Directions in Research and Writing, Text and Discourse, edited by Martin Nystrand and John Duffy, University of Wisconsin, 2003, pp. 84-115.

Barnett, Scott and Casey Boyle. Introduction: Rhetorical Ontology, or, How to Do Things with Things. Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things, edited by Scott Barnett and Casey Boyle, University of Alabama Press, 2016, pp. 1-17.

Boyle, Casey. Writing and Rhetoric and/as Posthuman Practice. College English, vol. 78, no. 6, 2016, pp. 532-554.

Brooke, Collin and Thomas Rickert. Being Delicious: Materialities in Web 2.0 Application. Beyond Postprocess, edited by Sidney Dobrin, J.A Rice and Michael Vastola, Utah University Press, 2011, pp. 163-179.

Bizzell, Patricia. The Intellectual Work of Mixed Forms of Academic Discourses. Alt/Dis: Alternative Discourses and the Academy, edited by Christopher Schroeder, Helen Fox, Patricia Bizzell, Boynton/Cook, 2002, pp. 1-11.

Carter, Genesea. Mapping Students’ Funds of Knowledge in the First-Year Writing Classroom. Journal of Teaching Writing, vol. 30, no. 1, 2015.

Cooper, Marilyn M. The Animal Who Writes: A Posthumanist Composition. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019.

Dobrin, Sidney. Writing Posthumanism, Posthuman Writing. Parlor Press, 2015.

Fraiberg, Allison. Houses Divided: Processing Composition in a Post-Process Time. College Literature, vol. 29, no. 1, 2002, pp. 171-180.

Gallegos, Erin Penner. Mapping Student Literacies: Reimagining College Writing Instruction within the Literacy Landscape. Composition Forum, vol. 27, 2013. https://compositionforum.com/issue/27/literacies.php.

Graff, Gerald and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say/I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing, W.W. Norton & Company, 2014.

Hawk, Byron. A Counter-History of Composition: Towards Methodologies of Complexity. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007.

---. Reassembling Postprocess: Toward a Posthuman Theory of Public Rhetoric. Beyond Postprocess, edited by Sidney Dobrin, J. A. Rice and Michael Vastola, Utah University Press, 2011, pp. 75-94.

Hayles, Katherine. How We Become Posthuman: Virtual Bodies In Cybernetics, Literature, And Informatics. The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Kent, Thomas. Post-Process Theory: Beyond the Writing-Process Paradigm. Southern Illinois UP, 1999.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Lynch, Paul. Shadow Living: Toward Spiritual Exercises for Teaching. College English, vol. 80, no. 6, 2018, pp. 499-516.

Mara, Andrew and Byron Hawk. Posthuman Rhetorics and Technical Communication, Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 1, 2010, pp. 1-10.

Matsuda, Paul K. Process and Post-Process: A Discursive History. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 12, 2000, pp. 65-83.

Muckelbauer, John and Debra Hawhee. Posthuman Rhetorics: ‘It’s the Future, Pikul. JAC, vol. 45, no. 4, 2000, pp. 767-774.

Rutherford, Kevin and Jason Palmeri. The Things They Left Behind: Toward an Object-Oriented History of Composition. Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things, edited by Scott Barnett and Casey Boyle, University of Alabama Press, 2016, pp. 96-108.

Taylor, Mark C. The Moment of Complexity: Emerging Network Culture. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Trimbur, John. Taking The Social Turn: Teaching Writing Post-Process. College Composition and Communication, vol. 45, no. 1, 1994, pp. 108-118.

Young, Richard, Alton Becker, and Kenneth Pike. Rhetoric: Discovery and Change. Harcourt, 1970.

Mapping a Network from Composition Forum 47 (Fall 2021)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/47/mapping-network.php

© Copyright 2021 Brent Lucia.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 47 table of contents.