Composition Forum 45, Fall 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/

Remaining Inclusive: Crisis Correspondence Packets for Student Completion of Spring 2020 (COVID19) Writing Courses

Abstract: This program profile describes the process the Writing Program at the University of Arizona took to create a pathway to course completion for students during the pandemic-induced remote transition in Spring 2020. While the majority of students continued to have access to the hardware and software necessary to complete the term online, some students did not have these critical access requirements. We designed an independent study style correspondence packet that harkens back to traditional distance education offerings. Recognizing that students might not have access to the web or library for research, instructional materials, or printers, the packets allowed students to use the resources to which they had access and mail in their materials to complete their courses. Designing and implementing this course packet allowed us to continue our mission of inclusion in a moment of crisis by meeting our students where they were as they were displaced from the institutional spaces they had been relying upon to finish their coursework. This work has given us language to use in helping our instructors continue to support their students in crisis.

Context: UArizona

Like many large state universities, January 2020 found the University of Arizona (UArizona) starting a relatively normal spring term. Housed in the Department of English, we are a large Writing Program that offers and manages traditional first-year composition courses (referred to as “Foundations” writing at UArizona), one 4-credit studio option, and three second language writing course offerings that also fulfill the Foundations writing requirement. For the past few years, our semesterly enrollments were steadily increasing but still tightly circulating around offering approximately 350 sections to 6,000 students. In Spring 2020, we had 150 instructors, about two-thirds of whom were Graduate Teaching Assistants/Associates (GTAs). Like most GTAs in writing programs, they were instructors of record. The remaining instructors were adjunct (on semester contract) or Career Track (one-year or multi-year) lecturer or Career Track professor positions.

By Spring 2020, the UArizona Writing Program already had a well developed online program. When the university developed and started offering online undergraduate degrees in Fall 2015, the UArizona Writing Program started developing the online offerings to fulfill the Foundations writing requirement. From Fall 2015 to Spring 2020, the regular fall and spring online course offerings continued to increase as the Arizona Online (AZOnline) campus continued to grow. Traditionally the Writing Program offered very few online course offerings outside of AZOnline during the fall semester; we wanted traditional, main campus students to acclimate to their new context at UArizona. Typically we offered more online and hybrid ENGL102 courses during the spring semester. By the 2019-20 academic year, the UArizona Writing Program was offering around 14 online courses each term for AZOnline. Our summer online offerings, however, skyrocketed during the five year period. By Summer 2019, all but a handful of summer writing courses were offered online. AZOnline used the Quality Matters course design assessment program to ensure online course quality. However, because the Writing Program always had a large number of relatively inexperienced teachers in the summer that were new to both online and condensed courses, we also iteratively designed, assessed, and revised pre-designed online courses (Rodrigo and Ramirez).

As a program, we have a set of principles on teaching writing that inform our course outcomes. At the core of those principles is the premise that we value equity and inclusion, and we hold those values as the core of our work in the program. Since it was the spring term, the vast majority of our course offerings were ENGL102; ENGL102 emphasizes rhetoric and research across contexts. The student learning outcomes for ENGL102 in Spring 2020 were:

-

Analyze the ways a text’s purposes, audiences, and contexts influence rhetorical options.

-

Respond to a variety of writing contexts calling for purposeful shifts in structure, medium, design, level of formality, tone, and/or voice.

-

Employ a variety of research methods, including primary and/or secondary research, for purposes of inquiry.

-

Evaluate the quality, appropriateness, and credibility of sources.

-

Synthesize research findings in development of an argument.

-

Compose persuasive researched arguments for various audiences and purposes, and in multiple modalities.

-

Adapt composing and revision processes for a variety of technologies and modalities.

-

Identify the collaborative and social aspects of writing processes.

-

Reflect on their progress as academic writers.

-

Reflect on why genre conventions for structure, paragraphing, tone, and mechanics vary.

-

Identify and effectively use variations in genre conventions, including formats and/or design features.

-

Demonstrate familiarity with the concepts of intellectual property (such as fair use and copyright) that motivate documentation conventions.

The Writing Program predominately promotes curricular alignment through two mechanisms: shared student learning outcomes and required course instructional materials (e.g., textbooks).

In the middle of Spring Break, UArizona announced that the University would be returning from Spring Break three days later than anticipated and that all courses needed to be shifted to online instruction. All of a sudden, large groups of faculty and students who had no intention or interest in online teaching and learning were required to shift to this modality. Because of the training requirements to teach online in the Writing Program, a large number of our faculty had at least spent some time thinking about online teaching and learning. Over half of our returning GTAs had at least one experience teaching with one of the pre-designed courses. That being said, we still had all of our new GTAs, most without online teaching experience, and a large number of adjunct and Career Track faculty who had never wanted to teach online and had not prepared for it.

More importantly, however, we had students not prepared for the remote transition to online learning. And whether or not they were prepared, there was a small subset of students who did not have access to the hardware, software, and/or internet connectivity to complete their Spring 2020 semester online from their home or another location off campus. Although most faculty and administrators know that not every student has access to a computer and internet connection, technological access is still generally considered ubiquitous to students enrolled in higher education. For example, during their 2008 annual national study of undergraduate students and information technology, EDUCAUSE stopped asking about basic cell phone ownership (Smith, Salaway, and Caruso 87) and in their most recent 2019 study did not ask about hardware ownership at all (Gierdowski). However, the University of Arizona has higher than average Indigenous (3.3%) student populations (University of Arizona, University Analytics and Institutional Research). Therefore, we knew we would have students who could not complete the term online; however, our Indiginous students who went home were not the only students who did not have consistent internet access. Some students may have had internet access, but they were sharing it with other people living in the same space. Other students only had access through their phones and mobile wireless provider and the costs were too prohibitive to complete all of their courses via the mobile hot-spots. Finally, we had students who were not only transitioning their courses online but were also transitioning their living spaces. For many students it was impossible to work while traveling home, and in some cases, sitting in quarantine.

As the Interim Director of the Writing Program (Author #2), the Associate Director of Second Language Writing (Author #3), and the Interim Assistant Director of Online Writing (Author #1), we had to come up with a plan to support all of our students; we felt that the administrative team had a responsibility to step in during a time of crisis to help support our faculty and students. Our statement on Principles of Teaching Writing explicitly indicates that “we approach writing instruction from the premise of diversity of inclusion.” Thus, addressing the problem of access was part of upholding our programmatic values of equity and inclusion.

Overview of The Correspondence Packet Plan

The plan was to offer a completion option to students who were forced to move out of their dorms (or other local housing) and return to homes that may or may not have had the necessary internet connection or technology to complete their now online writing courses moving forward. As distance learning scholars, two of us (Author #1 & Author #2) know that correspondence courses are not typically our best pedagogical choice; however, for the students we were trying to reach, it was the only option. Our third author (Author #3), a Second Language Writing (SLW) scholar and administrator over the SLW writing courses, also saw an independent study option as a way for international students travelling home (and likely to experience quarantine conditions) to finish out the course. And, since everyone at UArizona was struggling in March 2020, this was a plan that we had to design, develop, and implement within the Writing Program.

Correspondence and independent study style courses have a long history in distance education offerings; in fact, they are the history of distance education (Gigantino; Moore and Kearsley; Sumner). Most histories point to the fact that the founder of the University of Chicago, William Rainey Harper, emphasized correspondence courses as part of the University’s mission as the key moment in university offerings of distance education programs (Gigantino 268). Although AZ Online only started in 2015, the University of Arizona has a prior history of distance education offerings as evidenced by digital catalog archive copies of Correspondence Course or Independent Study catalogs as early as 1935 and late as 1985 (University of Arizona, “1933-1934 Correspondence Courses” and “1984-1985 Independent Study”).

Some correspondence courses in higher education became commonly referred to as independent study (Moore & Kearsley 20). Especially in the United States, the use of independent study referenced both the fact that the student was independent from the instructor but also increasingly came to account for the student’s autonomy in “making decisions concerning their learning” (Moore & Kearsley 23). And although the primary purpose for our offering of a correspondence course packet as a way for students without computer or internet access to complete their writing courses in Spring 2020, as outlined below, we also emphasized the need for students to take ownership of their learning.

Finally, critiques of correspondence and independent study style distance education courses usually emphasize the unidirectional communication pathways that do not allow for students to easily interact with the instructor and make interaction with fellow students almost impossible (Sumner 272). Especially since our student learning outcomes emphasize both rhetorical concepts like audience as well as process steps like peer review, it was critical that we also build in prompts that guided students to think about authors and audiences, as well as seek out and obtain feedback on their drafts as part of their writing process.

Enacting the Plan

Before we tell you exactly what we did, we want to be clear that the overview of the plan described above is about as much planning as we could manage due to the circumstances. The rest is a description of what happened, and is intended to describe some of those “we wish we had” moments that would have made some of our other processes easier. Hindsight can cause us to be critical, but this is intended to be openly reflective of the process.

Designing the Correspondence Packet

The Correspondence Packet option would take the place of eight weeks worth of instruction, and so we began with an outline of two writing tasks: an analysis paper and a reflective piece. The analysis papers were specific to the focus of a typical course in the Foundations Writing courses (ENGL101/102) and their second language writing (107/108) and honors (109) equivalents. The ENGL101/107 assignment options focused on genre analysis (Appendix 1) and the ENGL102/108/109 assignment options focused on rhetorical analysis (Appendix 2). This reflected the content that each course had most likely provided before Spring Break in face-to-face classes. After we determined the focus of the analysis essays, we decided to give students two options for each class: one that focused on news sources and one that focused on advertisements. We wanted to give students the opportunity to reflect on what was happening in the world around them and how that information is structured and delivered, but we also recognized that not all students would want to focus on the news in order to protect their mental health (Appendices A and B). What was paramount in both cases was making sure that students could use what they had already learned earlier in the semester (based on our outcomes and programmatic textbooks) and what they had access to in order to complete the assignments. We sought to build on learning we assumed had taken place while emphasizing process-based writing instruction in a context where students had little to no access to the internet and potentially to other digital technologies.

This meant we catered to that potential student without access to technology or the internet. Since our required textbooks are also delivered digitally, students did not have access to their usual instructional materials either. To help complete the assignments we suggested sources such as word of mouth, print sources, billboards, television sources, etc. The reflective portfolio assignment options (Appendix 3) involved either an essay or a fill in the blank memo that had students think about and reflect on the work they did during the whole of the semester. This packet included a cover letter (Appendix 4) that first communicated our pedagogy of care, provided guidance to students on how to complete the packet, and pointed them to resources on campus that might be relevant (e.g., changing to a P/F option). We referred to the materials as the “packet” or “course packet” to students and instructors, as the “correspondence” aspect of what we were doing is online pedagogy jargon.

Identifying “Missing” Students-Reaching out to Instructors

While the assignment prompts were being drafted, we also worked with staff on logistics like creating a survey where instructors could report students they either had not heard from since the transition or students they had heard from but who did not have access to the internet. For each student the instructor was concerned about, we asked:

-

Student Name

-

Course Information (Course, Section #), example: ENGL102, section 1

-

Student interaction by March 25, 2020 (please check all that apply):

-

Student has not submitted any work and/or attended any synchronous activities.

-

Student has contacted me and says is unable to participate as the course is currently constructed

-

I have not been able. to communicate with the student in any way.

-

-

Any specific comments, concerns, or information about this particular student?

Once the survey questions were collected, a spreadsheet was generated, and the responses were coded by the larger administrative team. Students in the survey fell into 1 of 4 categories:

-

Non-communicating

-

Non-participating

-

Not participating/communicating at first but then participating

-

International (overlapped with other categories)

We used these codes to reach back out to instructors a few weeks later, and in the meantime set our support team to gather information in order to reach these students.

Mailing Packets

Department of English staff and student workers set to work calling students on the list that were either non-communicating or non-participating to ask for a good mailing address to send the course packet. We drafted scripts for student workers to use when calling students to verify mailing addresses. These scripts (Appendix 5) included the reason they were calling and some information about who to contact about changing grade options to P/F and other student support services.

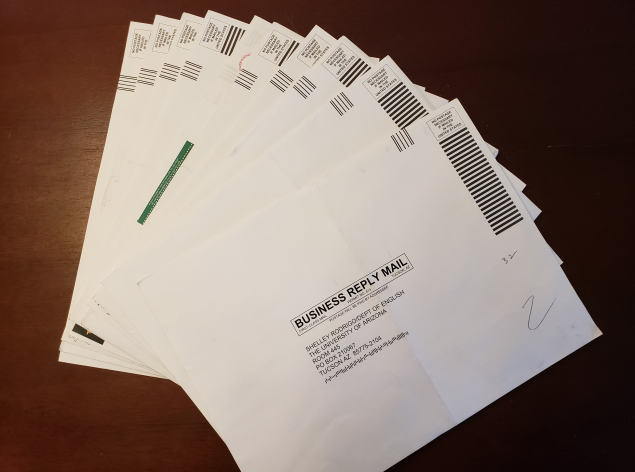

For students who were reached, the packet was mailed to that address; otherwise, the address the university had on file was used. During the scripted phone calls, some students indicated that they did not want a packet because they had withdrawn or would be withdrawing from the course. In total, we mailed over 100 packets. The financial logistics included the cost of photocopying and mailing packets. We ended up using the “postage paid if mailed in the US” option with the United States Postal Service. This option allowed us to mail packets to students with pre-printed, pre-addressed envelopes with “no postage necessary if mailed in the United States” codes to students. We would only be responsible for payment when the packet was mailed back.

For our international students enrolled in second language writing classes, the packet was adjusted for those courses and then emailed as we were unsure where exactly our international students were. They may have stayed in the U.S., but some also went to their home countries. In addition, the international students we were working with were non-participating but for the most part did have some access to internet. We also knew that international mailing might pose a delay beyond the end of the semester.

We knew that students would be anxious, confused, and would want to talk to somebody with authority. We set up a Google Voice number that collected voicemail and text messages. We included the Google Voice number as part of the instructions in the correspondence packet (Appendix 4) and left it with any voicemail messages (Appendix 5). The Google Voice number was connected to the account of the Interim Director of the Writing Program (Author #2). Throughout the second half of April through early summer students called or texted the number asking questions about what the packets were or how they needed to complete the work; they also communicated to confirm receipt of their submissions.

Working with Instructors

There were a number of ways we worked with instructors to determine the best ways to help students finish the semester and to provide a final grade. Early on it became apparent that some non-participating students were able to come back to the course after returning home. In these cases, their non-participation had mostly been due to travel either domestically or internationally. A few weeks after we had asked instructors to report non-communicating students, we turned back to instructors with another survey asking if students had since reached out to them to complete the course and, if so, if the instructor would then take over finishing the course with the student. If it could be managed, we felt finishing the course out with their instructor was the best option.

We sent out a new survey to instructors, and if they indicated that the admin team should take over finishing the course, we asked the instructor to report (in a secure format) what grade the students had earned before spring break. This happened at about the same time that packets were sent. Because packets had to be mailed using USPS, we wanted to make sure they were sent while also reaching back out to the instructors. For international students, since this was a smaller population and we knew we would be sending packets by email, we were able to work closely with instructors to determine whether a packet should be sent.

This resulted in instructors reporting students who were newly not participating in the course. We knew there would be new non-participating students, but we did not anticipate instructors reporting new students in the survey. Because it was reported in the survey, we felt obligated to reach out to these students. Some instructors had not been reporting students because they knew they were moving. There were also many students who had been reported early on as not participating but even a week later had rejoined the course. This reflected the changing situation of many students: some did not immediately return home, so early participation was possible; others were in transit during the first reporting period but were able to eventually reconnect to a stable internet connection. To attempt to reach this new batch of students with limited access, we emailed a second round of domestic and international students. In addition, even after receiving packets, some students were able to rejoin the course.

We also had students who disappeared near the end of the course, and instructors who wanted to use the packet to help their students complete the semester. We made the packet available to instructors if they wanted to work with the student in that way. For final grades, there was also a lot of messaging we needed to provide to instructors so that they could understand the process. We needed to get pre-COVID shutdown grades from instructors so that we would know how to average those grades with the grade they received on the packet. We also needed to make sure that instructors indicated an “I” grade on their rosters for any students they had reported for the packet program. Since we knew packets might likely come to us after grades were due, we took on the responsibility of grading the packets and updating incomplete grades.

Because we had more than one survey go out, and instructors were unsure who they reported at which time, we took to crafting jigsaw messaging with specific instructions for each category that students fell into by mid-April:

-

Students that had been mailed packets and for whom the instructor had already reported a pre-spring break grade;

-

Students that had been mailed packets and for whom the instructor had not yet reported a pre-spring break grade;

-

Students who were reported in March (just after the shutdown), but were emailed a packet because we could not locate a good address, and the instructor had reported a pre-spring break grade;

-

Students who were reported in March, but were emailed a packet because we could not locate a good address, and the instructor had not yet reported a grade; and

-

Students newly reported on the survey sent on April 13th when we were asking for grades.

Throughout the process of checking in with instructors and gauging whether or not the administrative team needed to continue to work with students, we encouraged students and instructors alike to work together to complete the course. The administrative team stepping in was the last resort, and it felt worth the work for us when we received the packets.

Receiving Packets

We received 19 packets from students who were unable to finish the course. We received 12 packets through USPS (one of which had been lost in the mail, but has since been resubmitted); half of which included hand-written work. We received 7 more through digital submission. Nineteen students is an entire section of a Foundations Class (in Spring 2020, our classes were capped at 19 students). We are also aware of 56 students who received packets but ultimately completed the course with their instructor of record as instructors reported that they were working with those students.

Seven of the mailed in packets completed analyses about news coverage of COVID-19, the other five completed comparative analysis of advertisements. Of the seven packets received via email, all but one chose to focus on a rhetorical analysis of advertisements (mostly print ads). One student took the opportunity to conduct a genre analysis of conversations around COVID-19, using conversations with family and classmates as their sources.

Assigning, Calculating, and Submitting Grades

We developed a rubric for the correspondence packet that reflected our focus on students’ sincere engagement with the content and completion of work. For example, in the current events analysis, they analyzed at least three specific news publications. In this way, the rubric was aligned with labor-based and specifications-based approaches to grading (Inoue; Nilson). Students received full credit for the packet if they completed all portions. We also acknowledged that messaging for the packets may have been a bit confusing, as some of the students who returned their packets did not complete a portfolio reflection; they only completed the genre analysis or rhetorical analysis assignment. We thus gave these students the benefit of the doubt and graded those packets as complete.

In calculating the final grade, we placed more emphasis on the pre-Spring Break grade as reflective of what students were capable of in the class, and thus weighted the packet grades as 40%. Many students had also switched to a P/F option for the course, which made assigning final grades a bit more straightforward.

In order to submit grades, we were added as instructors to 73 sections so we could change the “I” grades to the earned grade. With well over 100 students and 73 sections, this took some time. We prioritized the grades for the students that had submitted packets and worked through the rest of the list to change the remaining grades. These needed to be changed in order for students to re-enroll in the course for fall or summer. In late July, an international ENGL107 student who had been part of the group that received an incomplete as a placeholder during portfolio grading reached out to one of us because the grade had not yet been assigned. This turned out to be beneficial for the student because we could direct them to our staff to enroll in the correct course for fall; however, it did put more urgency in making sure the rest of the grades were changed to the earned grade so students could re-enroll if they needed to.

Reflection on the Process of Enacting the Plan

This work was reactionary. It was reactionary at its inception and continued to be reactionary at each turn because we were working with students and instructors in crisis. Our critical reflection is a combination of sharing what we did while acknowledging what might have worked better; all things considered, we’re proud of the steps that were taken. People don’t normally fit into a box or category, and even less so when we’re in an unprecedented pandemic. There are many things hindsight lets us see: for instance, the messaging could have been better, and we didn’t anticipate instructors waiting to see if their students showed back up. Initially, we anticipated using the packets for the small subset of students who had no connectivity at home. We had to recognize other reasons why students had limited or no access to class participation. For example, international students who travelled home during the pandemic were often quarantined for two weeks, with access to nothing but a cell phone, thus rendering their participation impossible.

It is difficult to say what we would have done differently. We like to think if we had had more time on a daily basis, we might have better thought out some logistics or smoothed the edges around some of the communication. For example, some students who submitted the final packet only submitted the essay, not the reflection assignment that acted to fulfill our portfolio requirement. Obviously the instructions were not clear enough and some students did not understand two different artifacts were required. If we had more time, we might have had more instructors, or even a few sample students, read the assignments and give us feedback. Designing and delivering this alternative completion option for the students was just one of the many, mostly emergency, administrative balls we were juggling. These are just some examples of those times when we let out a sigh because we knew if we were not also in crisis mode, that it could have gone smoother.

However, instead of focusing on what we would have done differently, we’d like to reflect upon the fact that we focused on our values. It was of the utmost importance that we try to provide every student with the option to complete their writing course during the Spring 2020 term. Of course, we were unable to contact all of them. Of course, many still withdrew or failed their courses. However, we know that we took the extra time to design, develop, and implement an option that invited students with access issues, however broadly defined, to finish their Spring 2020 writing courses.

In the few interactions we had with students completing the packet, students seem to have appreciated the opportunity. Instructors, who were worried about their students while also worrying about their own lives changing, expressed relief that we shared the labor. In fact, we’ve been asked if we will do a course packet this fall as we see students struggling because of the ongoing pandemic. At heart, correspondence course pedagogy and writing studies pedagogy do not align, so we do not plan to continue using course packets or suggest others use them. The correspondence course packet itself was a necessary, in the moment of crisis pedagogy that was appropriate for the time because the students in spring 2020 started their courses with the expectation that the institution would provide access to the internet and a computer for the duration of their courses. While we are still seeing pandemic related issues for our students, our current students were expected to have their own access to technology and the internet; however, developing the packet out of our core values and outcomes has given us the language of “core assignments” and “unit/module package” to help instructors narrow down to essential assignments to help students who are now struggling.

Appendices

- Appendix 1: ENGL101/107 Major Project Assignment Prompt

- Appendix 2: ENGL102/108/109H Major Project Assignment Prompt

- Appendix 3: Portfolio Reflection Assignment Prompt

- Appendix 4: Correspondence Packet Cover Letter

- Appendix 5: Telephone Scripts

Appendix 1: ENGL101/107 Major Project Assignment Prompt

Major Project Instructions

For this assignment, you’ll write a short (2-3 typed, 4-6 handwritten page) analysis. The purpose of this assignment is to use your knowledge from the first half of the semester and apply it to something in the world around you.

If you are enrolled in ENGL101/107/101A, please select one of the two options below:

1. Current Events Genre Analysis: Consider how you are receiving information about current events (radio, TV, newspaper, word-of-mouth). First, select 3 specific news publications, on the same topic, to use as sources for this task. For example, three separate CNN Nightly Newscasts, or 3 separate local newspaper articles, or 3 separate conversations you've been in ALL about the same topic. For each source, take notes that identify key points, how those points are being made, and why those points are being made. You should also take notes on the similarities and differences between each source. Then, working from your notes, write paragraphs for each source that discuss:

-

the purpose or “main idea” of the source

-

the ways ideas are communicated in the source (i.e. the organization, visuals, etc.) and

-

a discussion of the similarities and differences between the source and the others you’ve selected, specifically identifying elements that may be considered conventions

In your write up, you’ll want to start with an introduction that includes some background information about the sources you selected and a thesis statement that synthesizes the conventions of this specific type of news source. Then, include your paragraphs that you wrote about each source/even. For each of those body paragraphs, start with a topic sentence clearly outlining your point for that paragraph, offer examples or proof, and think through your points so that we can understand the material the way you do. End your essay with a conclusion that sums up your findings.

2. Advertisement Genre Analysis: Consider the genre of advertisements. First, select two advertisements from the same type of source (if you select TV commercials, then select two TV commercials). In selecting your advertisements, consider word-of-mouth advertising (members of your household), TV ads, newspaper ads, radio ads, magazine ads, etc. For each advertisement, take notes that identify the purpose, how that purpose is being achieved, and why it’s effective. Your notes should include the similarities and differences between the two advertisements specifically focusing on identifying strategies used by the writers/creators. Also consider how each advertisement is delivered (on TV, in print, etc.) the impact of the conventions of a particular advertisement. Then, working from your notes, write paragraphs that discuss

-

the purpose of each advertisement

-

the ways ideas are communicated in the source (i.e. the organization, visuals, etc.) and

-

a discussion of the similarities and differences between the advertisements, specifically identifying elements that may be considered conventions of the genre

In your write up, start with an introduction that explains/describes the advertisements and a thesis statement that synthesizes the conventions of this specific type of advertisement. Then, include your paragraphs that you wrote about each source/even. For each of those body paragraphs, start with a topic sentence clearly outlining your point for that paragraph, offer examples or proof, and think through your points so that we can understand the material the way you do. End your essay with a conclusion that sums up your findings.

Submit:

After you’ve written a draft, please have at least 1 person in your household review it and provide feedback. Edit your work based on this feedback, and submit the following:

-

Final Draft of your analysis essay

-

A reflective paragraph that discusses the feedback you received, how you processed/used it, and what your experience was with this assignment.

Appendix 2: ENGL102/108/109H Major Project Assignment Prompt

Major Project Instructions

For this assignment, you’ll write a short (2-3 typed, 4-6 handwritten page) analysis. The purpose of this assignment is to use your knowledge from the first half of the semester and apply it to something in the world around you.

If you are enrolled in ENGL102/108/109H, please select one of the two options below:

1. Current Events Rhetorical Analysis: Consider how you are receiving information about current events (radio, TV, newspaper, word-of-mouth). Select 2 different information news sources on the same topic (i.e. one newscast, one newspaper article). Take notes, for each source, on the main idea, the purpose, the intended audience, how the author is making their point (what evidence are they using, is it reliable, etc.), if it’s effective, what the writer/speaker is assuming about the audience, and how each source communicates the ideas differently. Then, working from your notes, write analysis paragraphs that discuss:

-

the main idea, point, argument being made

-

the intended audience

-

how the argument is being made

-

why the argument is being made in this particular way

In your write up, start with an introduction that provides some background and a thesis statement that synthesizes effectiveness of the communication of the main idea. Then, include your analysis paragraphs, making sure you start with a topic sentence clearly outlining your point for that paragraph, offer examples or proof. End your essay with a conclusion that sums up your findings.

2. Advertisement Rhetorical Analysis: Select two advertisements. These advertisements should be for two different products be or intended for two different audiences and can be from TV, radio, word-of-mouth, or print sources (billboards, magazines, etc.). Analyze the differences in the rhetorical approaches of the writers/speakers. Take notes, for each ad, on the main idea, the purpose, the intended audience, how the author is making the point (what evidence are they using, is it reliable, etc.), if it’s effective, what is being assumed about the audience, and how each ad makes the point differently. Then, working from your notes, write analysis paragraphs that discuss:

-

the main idea, point, argument being made

-

the intended audience

-

how the argument is being made

-

why the argument is being made in this particular way

In your write up, start with an introduction that describes/explains the advertisements and has a thesis statement that synthesizes effectiveness of the advertisements. Then, include your analysis paragraphs, making sure you start with a topic sentence clearly outlining your point for that paragraph, offer examples or proof. End your essay with a conclusion that sums up your findings.

Submit:

After you’ve written a draft, please have at least 1 person in your household review it and provide feedback. Edit your work based on this feedback, and submit the following:

-

Final Draft of your short analysis

-

A reflective paragraph that discusses the feedback you received, how you processed/used it, and what your experience was with this assignment.

Appendix 3: Portfolio Reflection Assignment Prompt

Portfolio

In this final assignment, you will write an essay in which you reflect on your learning this semester. The goal of this essay is to demonstrate your understanding of the things you learned. You have two options for writing this essay.

Option 1

Read through the following topics and pick a few (3-5) that you think you can spend some time reflecting on. Write an essay, of about 2-3 typed/4-6 handwritten pages, based on the topics you select. Make sure that you spend some time discussing specific examples, and explaining how those examples helped you to learn the topics you’re writing about, even if only partially.

-

Key terms or concepts: What terms (such as genre or rhetoric, for example, depending on your class) have you learned in this class and what do they mean to you?

-

Readings: What things have we read that stick out to you? Why do they stick out? What things have you retained from these readings?

-

In class or online activities: What in-class or online activities have you done in which you think you learned something from?

-

Writing Process: Describe and/or draw your writing process. What can you say about this? What works and what doesn’t? What technologies do you use and why (also, remember that pen and paper are technologies)?

-

Major Assignment: Reflect on your major assignments (for example, a genre analysis or rhetorical analysis). What did you write about and why? What did you learn from writing it?

-

Self-Assessment: Assess your work in this class. What have you done well and what can you improve on in the future?

Option 2

Fill in the template on the next page, which asks you to reflect on the course goals. All you have to do for this option is fill in the template as directed. When identifying four focus areas, you can choose from the 6 reflection topics in option 1 or the four Foundations Writing Program goals:

-

Goal 1: Rhetorical Awareness: Learn strategies for analyzing texts’ audiences, purposes, and contexts as a means of developing facility in reading and writing.

-

Goal 2: Critical Thinking and Composing: Use reading and writing for purposes of critical thinking, research, problem solving, action, and participation in conversations within and across different communities.

-

Goal 3: Conventions: Understand conventions as related to purpose, audience, and genre, including such areas as mechanics, usage, citation practices, as well as structure, style, graphics, and design

-

Goal 4: Reflection and Revision: Understand composing processes as flexible and collaborative, drawing upon multiple strategies and informed by reflection.

Memorandum

To:

From:

Date:

RE:

Add an introductory paragraph that provides an overview of your learning in the course. Conclude with a sentence that transitions to the course goals; you must cover 4 goals or reflection topics. Feel free to fill in this template or write/type on separate paper.

<half-page of empty space>

Goal or Reflection Topic #1:

Offer at least two concrete examples (artifacts) of how you have met this outcome through the work you did (not the work you were asked to do). Your paragraph should describe the artifacts and articulate how the artifacts show you working toward meeting the outcome.

<half-page of empty space>

Goal or Reflection Topic #2:

Offer at least two concrete examples (artifacts) of how you have met this outcome through the work you did (not the work you were asked to do). Your paragraph should describe the artifacts and articulate how the artifacts show you working toward meeting the outcome.

<half-page of empty space>

Goal or Reflection Topic #3:

Offer at least two concrete examples (artifacts) of how you have met this outcome through the work you did (not the work you were asked to do). Your paragraph should describe the artifacts and articulate how the artifacts show you working toward meeting the outcome.

<half-page of empty space>

Goal or Reflection Topic #4:

Offer at least two concrete examples (artifacts) of how you have met this outcome through the work you did (not the work you were asked to do). Your paragraph should describe the artifacts and articulate how the artifacts show you working toward meeting the outcome.

<half-page of empty space>

Add a paragraph summarizing your takeaways and successes and suggesting how you might apply what you’ve learned in future contexts.

<half-page of empty space>

Appendix 4: Correspondence Packet Cover Letter

Dear Foundations Writing Student,

First, we hope you’re doing well and taking care of yourself amid our current crisis. You’re receiving this packet because your writing instructor from ENGL101/102/107/108/109H has been unable to reach you since Spring Break or you indicated that you had limited access to the internet/technology. This packet of work is intended to help you satisfy the remaining course requirements for your Foundations Writing course. This satisfies the remaining requirements by asking you to apply what you learned in a small assignment and reflect on what you learned in a reflection letter.

If you are able to complete the work, then your packet (no postage if mailed in the US) should be postmarked no later than May 13th. If you are unable to meet this deadline or unable to submit this packet for other reasons, please text or leave a voicemail at

Below you will find some resources, in case you haven’t received them.

Take care,

The UArizona Writing Program

UArizona Resources

P/F option

The University has decided to allow students to elect to have a class converted from A/B/C/D/E grading scheme to P/F. Before making a decision, we recommend that you first contact your advisor to determine how you would be expected to satisfy the Mid-Career Writing Assessment (MCWA). If you would like to do this, you need to contact the Registrar (520-621-3113) by May 6th. If you happen to be able to access the internet, you can find more information at: https://registrar.arizona.edu/coronavirus-covid-19-information

Grade Replacement Option

Students may repeat any course taken during the Spring 2020 term without having the subsequent attempt count towards grade replacement opportunity (GRO) or repeat option limits. The GRO option remains only for classes in which a C, D, or E grade is earned, but will be. If you have questions, please contact the Registrar (520-621-3113).

Other Resources

You can get in touch with a Support. Opportunity. Success. (SOS) specialist, and they can help. Text SOS to 97779 or, if you have internet access, visit: https://bit.ly/34dSgkU (the URL is case sensitive).

Appendix 5: Telephone Scripts

Outreach to Students w/o Access (confirmed by instructor communication)

Hi! Can I speak to __________.

Hello! I’m _________ from the Writing Program at the University of Arizona. I’m reaching out because your instructor reported that you have no or limited internet access. We would like to mail you a packet with some assignments to complete the remaining requirements for your course. Can you give me a good mailing address?

We also wanted to let you know that the University is providing some more flexible grading options. You should contact your advisor to talk about your options. I can give you the phone number for the registrar (520-621-3113) and the University has a number you can text to reach someone from Student Success. Text SOS to 97779.

Outreach to Students who haven’t communicated (as reported by Instructors)...

Hi! Can I speak to __________.

Hello! I’m _________ from the Writing Program at the University of Arizona. I’m reaching out because your instructor reported that they have received no communication from you since after Spring Break. We would like to provide the opportunity to complete your writing course. To do so, we need to mail you a packet with some assignments to complete the remaining requirements for your course. Can you give me a good mailing address?

We also wanted to let you know that the University is providing some more flexible grading options. You should contact your advisor to talk about your options. I can give you the phone number for the registrar (520-621-3113) and the University has a number you can text to reach someone from Student Success. Text SOS to 97779.

Guidance if Student has Questions about Writing Program

If the student insists on talking to someone in the WP, tell them they can call and leave a voicemail and/or text the following number: (###) ###-####. Someone from the WP will get back to them.

Guidance if Leaving a Message

Recite the two paragraphs above. Then say:

So that we can mail you the packet to finish your writing course, please call and leave a voicemail or text the following number with your name and a good mailing address: (###) ###-####.

Please Close with some Kind Words like:

Take care of yourself!

Stay safe!

I know it’s tough; hang in there!

BearDown

Works Cited

Gierdowski, Dana C. ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2019. ECAR, 2019. EDUCAUSE, https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2019/10/studentstudy2019.pdf?la=en&hash=25FBB396AE482FAC3B765862BA6B197DBC98B42C.

Gigantino, James J. Correspondence Courses. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Online Courses, edited by Steven L. Danver, SAGE PUblications, Inc., 2016, pp. 267-70. SAGE Reference, doi:10.4135/9781483318332.n89.

Inoue, Asao B. Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. The WAC Clearinghouse & University Press of Colorado, 2019. WAC Clearinghouse, https://wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/labor/.

Moore, Michael G., and Greg Kearsley. Distance Education: A Systems View. Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1996.

Nilson, Linda B. Specifications Grading: Restoring Rigor, Motivating Students, and Saving Faculty Time. Stylus, 2014.

Rodrigo, Rochelle, and Cristina Ramirez. Balancing Institutional Demands with Effective Practice: A Lesson in Curricular & Professional Development. Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 3, 2017, pp. 314-28. doi:10.1080/10572252.2017.1339529.

Smith, Shannon, Gail Salaway, and Judy B. Caruso. The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology. ECAR, 2009. EDUCAUSE, http://www.educause.edu/library/resources/ecar-study-undergraduate-students-and-information-technology-2009.

Sumner, Jennifer. Serving the System: A Critical History of Distance Education. Open Learning, vol. 15, no 3, 2000, pp. 267-85. Taylor & Francis Online, doi:10.1080/713688409.

University of Arizona. 1933-1934 Correspondence Courses. The University of Arizona, 1933. University of Arizona Libraries, https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/623835.

University of Arizona. 1984-1985 Independent Study Through Correspondence Catalog. The University of Arizona, 1984. University of Arizona Libraries, https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/580486.

University of Arizona, University Analytics and Institutional Research. Enrollment. The University of Arizona, 2020. University Analytics and Institutional Research, https://uair.arizona.edu/content/enrollment.

Remaining Inclusive from Composition Forum 45 (Fall 2020)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/arizona.php

© Copyright 2020 Catrina Mitchum, Rochelle Rodrigo, & Shelley Staples.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 45 table of contents.