Composition Forum 40, Fall 2018

http://compositionforum.com/issue/40/

Review of John Tinnel’s Actionable Media: Digital Communication Beyond the Desktop

Tinnell, John. Actionable Media: Digital Communication Beyond the Desktop. Oxford UP, 2017. 280pp.

As digital rhetoric, writing, and communication have moved beyond the desktop, they have become increasingly dynamic both spatially and temporally: we often carry digital communication devices (from laptops to smart phones to Google glass) with us at all times and to all places. In some scholarly circles, this shift has been termed ubiquitous computing, or ubicomp for short, as coined by Mark Weiser (1991). Ubicomp means—and does—what it sounds like: computing that is everywhere, always. John Tinnell’s book, Actionable Media: Digital Communication Beyond the Desktop, thus addresses “a burgeoning phenomenon in digital culture: the rise of ubiquitous computing (e.g., smartphones, smartwatches, smartglasses, smart____) and the demise of desktops” (xi). His call in response to such a burgeoning phenomenon is the formation of actionable media: “to author the built environment” (xii).

Tinnell recursively defines actionable media in different contexts throughout the book, and it would be prudent to simply list a few definitions here:

- Actionable media “seek[s] to mitigate the separation of networked multimedia and local action, and to ground meaning making at the interstices” (14).

- “Ultimately, in coining actionable media, I mean to marshal scholarly attention toward texts or audiovisual works that incorporate local action on both a formal and hermeneutic level” (17).

- “Actionable media projects (composed of texts, audio, or images) prompt close readings of the live events occurring in one’s proximity” (19).

- Actionable media is “present at the scene of action and embedded in everyday objects” (41).

- “Actionable media producers author digital content and arrange networked capacities with the resolute intent to enhance contextual awareness, inform present actions, generate data from proximate actant-networks, and frame lived perceptions of a dynamic locale” (58).

- “Actionable media ecologies bond texts, software, and events together in a bilateral, enunciative assemblage. The composed work is irrevocably hospitable to proximate flux” (76).

- “With actionable media projects, texts and audiovisuals are encountered amid the proximate present, often while we are doing something else (in addition to reading); hence, their cultural value, as well as the rhetorical principles informing their production and analysis, will differ radically from more pronounced traditions involved words, sounds, and images (be they oral, print, or digital) that have been crafted for the deferred time of the conventional archival spaces” (82).

- “Actionable media projects envelop the spectacle...but they are not themselves the spectacle. They are instead the frame instead of the framed” (203).

Tinnell properly frames the emergence of ubicomp as a paradigm shift in the fields of rhetoric, writing, and communication. If we draw from Thomas Kuhn’s framing of a paradigm shift, which structures scientific revolutions and thus necessitates radical shifts and departures in epistemological terms, we can easily glean how the paradigm shift of ubicomp demands revolutionary approaches to, and understandings of, the metaphysical, ontological, and epistemological bases of rhetoric, writing, and communication (Kuhn 2012). “That is, while our devices hint at a new paradigm,” Tinnell writes, “the concepts and practices by which we engage with, think about, and create multimedia for those devices remain unattuned to emerging technocultural conditions” (26-27). In other words, as we will discuss below, the second shoe drops always drops first. The accident, as Paul Virilio puts it, is invented first by the technological invention: the invention of the ship was also the invention of the shipwreck (Virilio 2007). While this opens up myriad ethical and philosophical questions and concerns regarding digital technologies writ large, which will be addressed below, actionable media attempts to proactively—rather than reactively—solder the emergent technology of ubicomp with a specific and productive practice.

Tinnell substantiates the paradigm shift of ubicomp in both theoretical and practical terms. In terms of theory, Tinnell draws from Gregory Ulmer’s electracy, which contends that the emergence of the digital institution signals an apparatus shift (much like that from orality to literacy), and as such requires a new logic and metaphysics for the fields of rhetoric, writing, and communication (Ulmer 2004). Part of the project of electracy revolves around an emphasis on heuretics (the logic and art of invention), as distinguished from hermeneutics (the logic or art of interpretation), which is a fundamental condition of actionable media—to rhetorically author the immediate environment in situ. In even greater detail, Tinnell places ubicomp in general, actionable media in particular, within the context of Bernard Stiegler’s work on being and technicity (Stiegler 1998, 2008). For Stiegler, the history of technics is the history of being, whereas the two terms cannot be ontologically separated; with the rapid acceleration of the speed of digital technologies, however (or what Paul Virilio would term “dromology” [Virilio 1986]), we have been undergoing a “disorientation” (again, the second shoe always drops first) (2008). Actionable media presents the potential of ubicomp to reconstitute and properly reorient our ontological condition with the emergence of otherwise disorienting digital technologies, particularly by way of in situ rhetorical practices that take into account our given environment, space/place, proximal milieu, etc.

With such theoretical grounding, Tinnell also focuses on the practical application of actionable media. While noting that ubicomp in general, actionable media in particular, are still works in progress—that is, “these devices allow for computing while doing, but they’re not yet designed for it” (7)—Tinnell clarifies the distinction between actionable media, mobile media, and locative media. Mobile media, for example, “downplays the ubicomp mandate to make media actionable,” focuses on “personal ownership and sheer portability” (60), and “reduce[s] ubicomp to...medium-specificity” (61). As distinctly post-desktop, ubicomp and actionable media involve public authoring and attention to vast ecological networks, irreducible to a specific ubicomp medium. Locative media, on the other hand, “underscore[s] the merging of digital media and physical location” (66). As such, “locative media artifacts are stored on the spot, but they do not cohabit the scene” (68). In contradistinction, actionable media “casts attention toward practice and projects whereby text and context are fundamentally indivisible and processually co-constitutive” (68). Thus, while mobile media and locative media appear as ubicomp precursors to actionable media (proto-actionable media), they nonetheless fall short on the promise and full potential of ubicomp, as indicated by actionable media.

After detailing the distinctions between actionable media, mobile media, and locative media, Tinnell draws on avant-garde artistic practices (as relayed by Claude Monet, Augusto Boal, and Janet Cardiff) as models for how actionable media might develop over the course of our ongoing paradigm shift of ubicomp. Beyond the practical benefit of drawing from avant-garde artistic practices in terms of potential application, such a gesture also demonstrates the paradigmatic need in the age of ubicomp (electracy in general) to reposition rhetoric as an art. “On the more aesthetic and reflective end of the spectrum,” Tinnell notes, “actionable media grafts onto localities and materialities as a means to artistic or intellectual ends” (17). As the name—actionable media—implies, such an in situ rhetoric focuses not only on the heuretic aesthetics of the potential of ubicomp, but it further asks not what it is but what we can do with it—and how. That is, as Tinnell puts it, “art and ideas should be placed in spaces we choose to enter into on our time” (xvi). While the digital turn has developed more scientific approaches to rhetoric, writing, and communication—such as rhetorical code studies, or big data and rhetorical data visualization—Tinnell’s actionable media returns digital rhetoric, writing, and communication to the aesthetic sphere, which is a refreshing turn in the field of digital rhetoric, writing, and communication. As Tinnell argues, “even if code were to eclipse prose and become our lingua franca, we would still be dealing in argumentation, politicized statements, and the free play of interpretation. Programming is a form of writing best understood as an outgrowth from centuries of literacy” (87). Such constitutes the grammatology or grammaticization of ubicomp writing, on which Tinnell spends significant time (particularly in his critique of Derrida). Perhaps Tinnell’s book will persuade digital rhetors and rhetoricians to once again be rhetors and rhetoricians, rather than (attempting to be) computer programmers/analysts.

Figure 1. Augmented Reality Examples Compilation from Creative Commons. This video presents examples of augmented reality. Some approach the potential of actionable media; others are extensions of desktop computing and/or mobile or locative media.

It is important to note, however, that Tinnell’s theoretical infrastructure and his practical application should not be divorced, as the theoretical underpinnings inform the practice (Ulmer’s electracy and artistic practice), and the practice gestures back to the theoretical underpinnings (technological “doing” and Stiegler’s “postphenomenology”). In other words, Tinnell’s reminder that “Cicero’s concern was the separation of wisdom and eloquence” leads him to the “problem...[of] the separation of networked multimedia and local action” (3). That is, much as Stiegler notes, we should have never divided episteme, poiesis, and techne in the first place (Stiegler 1998, 2008). Actionable media is an attempt to rebridge that divide, both theoretically and practically. In doing so, actionable media moreover provides practical interdisciplinary service, insofar as it “mobilizes rhetoric’s figurative tradition to bridge research agendas from rhetorical theory, computer science, mobile communication, continental philosophy, media history, and digital art” (19).

In an attempt to avoid the utopic/dystopic dichotomy prevalent in scholarly discourse regarding digital computing during the first phase/decade (1990s), Tinnell recursively notes the productive potential (e.g., actionable media in the service of well-being) and possible social, political, economic, and ethical pitfalls of emerging ubicomp (e.g., texting while driving). Within the scope of Tinnell’s vision of an actionable media that is linked in situ with the environment (a smart ecology), the situation might be more complicated and dire than presented in the book. For example, while Tinnell details Bernard Stiegler’s concept of “disorientation” (Stiegler 2008), such a postphenomenological consequence of emergent computing systems (e.g., nanotechnologies) extends beyond the rupture of consciousness via tertiary retention when viewing media in real-time (Tinnell gives the example of live-broadcast television). Stiegler gives the example of banking system nanotechnologies—systems that make globally significant decisions in nanoseconds, a speed that exceeds deliberative human cognition (Stiegler 2008). These banking systems are nonetheless smart and ecological, insofar as the decisions rendered are based on complex algorithms that take into account a myriad of patterns happening in real-time (“smart ecology” delivered through the vehicle of digital technologies). The “disorientation” in this scenario is that, aside from humans creating the algorithms and setting the systems in motion, the human user is not—cannot—be involved in the process. These systems are thus not entirely autonomous (pseudo-autonomous, perhaps, as are self-driving cars), yet they are eventually divorced from human action.

Tinnell does take great pains to address the ethical issues that befall and beset ubicomp, including the appropriation of ubicomp by the logic of late capitalism (Stiegler’s banking example above). Nonetheless, Actionable Media at times either explicitly or implicitly endorses a posthumanist, new materialist, actor-network, and/or object-oriented conceptualization of ubicomp. This makes sense when one envisions smart environments built into complex media ecologies, and one would thus see the need to involve all actants, whether human or non-human, in the development of smart environments. Yet such does not come without a cost. Removing the rhetorical primacy or agency of the human in the construction of Tinnell’s vision of ubicomp affords a seamless ease for late capitalist logic to appropriate such a paradigm shift. In addition to Stiegler’s example of contemporary banking computers, self-driving cars have otherwise ethical decisions programmed into them. This might be for the best, but it is difficult to conceive of an ethics—or an even an ethos, at least in rhetorical terms—that removes the fundamental engagement of the human actant. If we concede that, “alas, computers were physical objects all along” (9), which they are and always were, we should be hesitant to ontologically flatten emergent technologies qua objects with the unique human capacity for ethics in our developing media ecologies. Ironically, the ethical concern that arises most frequently in Tinnell’s book is that of surveillance, which is only a concern if we privilege a sense of privacy, which is reducible to a coveting of human subjectivity.

While the field of digital rhetoric, writing, and communication has been inundated with scholarship regarding multimodality (Alexander and Rhodes 2014), new media writing (Morey 2014), rhetorical code studies (Beck 2016), big data visualization (Beveridge 2017), etc., Tinnell approaches ubicomp as a paradigm shift in desperate need of revolutionary rethinking and remodeling. This means, in my own biased reading of Tinnell’s book, in situ rhetoric that involves the proximate environment and in a way that involves a heuretic and aesthetic approach to digital composing. Insofar as ubicomp still, for the moment, involves the hybridization of physical (non-digital) environment and digital (yet still material) technologies, Tinnell’s book contributes to Jody Shipka’s vision of a “rhetoric made whole”: multimodality that extends beyond the mere screen and involves non-digital or non-computing components (Shipka 2011). In concert with proximate environment, ubicomp becomes “the frame rather than the framed” (203).

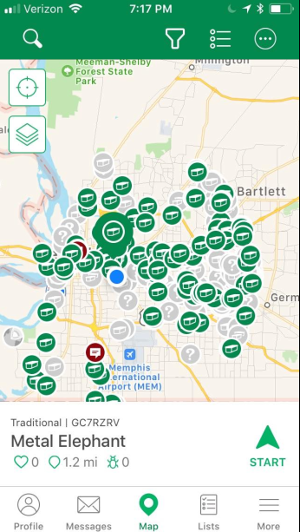

Figure 2. Geocaching map from Scott Sundvall’s iPhone. Geocaching provides one example of the potential of actionable media (a proto-actionable media) that moves toward a “rhetoric made whole,” combining Tinnell’s vision of ubicomp and Shipka’s conceptualization of multimodality.

Ubicomp affords actionable media by way of allowing us all to be rhetorical artists—in and within our proximal environment. Yet as Tinnell notes, while the potential for such writ large has been demonstrated, it takes more than that to make it actual. Such is why Tinnell ends by calling for the rise of the kairotic intellectual to replace the public intellectual—that is, for in situ intellectuals within an immediacy of space and time to overcome our fascination with intellectuals that merely happen to have a certain celebrity. Tinnell’s book is thus a signal call, an echo heard in the distance, familiar yet foreign, as we all adjust to this paradigm shift. Tinnell’s book could thus be one of two things: a prophetic declaration of where we must take digital rhetoric in its “third phase,” or a brilliant plea that fell on deaf ears. I would rather not live in the world that ends up situating his book in the latter sense.

Works Cited

Alexander, Jonathan and Jacqueline Rhodes. On Multimodality: New Media in Composition Studies. National Council of Teachers of English, 2014.

Beck, Estee. A Theory of Persuasive Algorithms for Rhetorical Code Studies. enculturation, November, 2016.

Beveridge, Aaron. Writing through Big Data: New Challenges and Possibilities for Data-Driven Arguments. Composition Forum, vol. 37, 2017.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. U of Chicago P, 2012.

Morey, Sean. The New Media Writer. Fountainhead, 2014.

Shipka, Jody. Toward a Composition Made Whole. U of Pittsburgh P, 2011.

Stiegler, Bernard. Technics and Time, Vol. I: The Fault of Epimetheus. Stanford UP, 1998.

---. Technics and Time, Vol. II: Disorientation. Stanford UP, 2008.

Ulmer, Gregory. Teletheory. Atropos Press, 2004.

Weiser, Mark. The Computer for the 21st Century. Scientific American, 1991, pp. 94-104.

Virilio, Paul. Speed & Politics: An Essay on Dromology. Semiotext(e), 1986.

---. The Original Accident. Polity Press, 2007.

Review of Tinnell, ACTIONABLE MEDIA from Composition Forum 40 (Fall 2018)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/40/sundvall-review-tinnell.php

© Copyright 2018 Scott Sundvall.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 40 table of contents.