Composition Forum 44, Summer 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/44/

Creando Raíces: Sustaining Multilingual Students’ Ways of Knowing at the Developing HSI

Abstract: In this program profile, we detail the design and implementation phases of an interdisciplinary first-year experience curriculum for multilingual students in the Creando Raíces learning community model at Humboldt State University. Our profile describes how we worked together as a professional learning community to integrate theories of writing development and transfer with culturally sustaining pedagogies. The coursework and academic structural supports of our model, such as its writing fellows program, supported student engagement in critical work that asked them to consider what it means to transfer one’s emerging and existing knowledges about language, literacy, discourse, schooling, and identity into and out of systems, institutions, and communities. In reflecting on our work across three semesters, our profile reveals ways that instructors, administrators and students can enact a multilingual, decolonial praxis as an approach to facilitating writing knowledge transfer.

In 2012, Elizabeth Wardle (referencing Bourdieu) described the ways that “fields are often structured so as to produce particular individual dispositions that are amenable to orthodoxy and, even better for the dominant groups, that lack the linguistic and critical tools to question doxa” (23). In academic fields, without (at minimum) pointing to language orthodoxy in Western post-secondary contexts, instructors teach and students learn writing in ways that privilege dominant/white discourse as academic discourse. While this is not a new understanding of how languages are/are not privileged in schools, current pedagogical models have not done much (yet) to engage students in analyzing the ideological underpinnings of language use, including how dominant discourse can be critiqued, resisted, transformed or reimagined. Perhaps this absence is connected to the discomfort that (white) faculty need to embrace in order to experiment with such resistance and transformation. But unless all faculty engage in transformational work around language and discourse in the classroom, the status quo holds, and the typical post-secondary student is asked to take up and perform dominant/white discourse without having the critical tools with which to critique and/or resist it. We argue here that exploring the theoretical and rhetorical connections between language and power with students is an essential component of enacting racial and social justice.

Our program profile describes how we linked curricula and academic supports to explore language and power with students in the Creando Raíces first-year learning community at Humboldt State University in 2019. This work involved implementing pedagogical designs that connect critical, socially just approaches to teaching, specifically Alim and Paris’ Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies, to teaching approaches that support writing knowledge transfer into and beyond academic contexts. We also confront some of the complications of this work, including that it is situated in a post-secondary institution where white discourse is privileged. In effect, part of the work of Creando Raíces was to disrupt the idea that a student’s ability to move through the university hinges on how well they can demonstrate their fluency in white discourse. Other crucial aspects of this work included developing curricula that centered students’ lived experiences through explorations of their languages, discourses, and ways of knowing.

Our Institutional Context and the Creando Raíces Model

The setting for the Creando Raíces (CR) program is Humboldt State University (HSU), a small institution in the California State University system. HSU was designated an Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) in 2013. While HSU has seen increased enrollment of undergraduate first-generation and Pell-eligible students over the last seven years (57% of first-time college students were first-generation and/or Pell-eligible in 2017), it remains a predominantly white institution and a HSI. In Fall 2019, demographic student data show enrollment at 63% non-underrepresented minority (45% identify as white) and 37% underrepresented minority (33% identify as Hispanic/Latinx; 3% identify as Black/African-American). Enrollment of Hispanic/Latinx students has increased by 14% since 2011 and is projected to continue to rise.

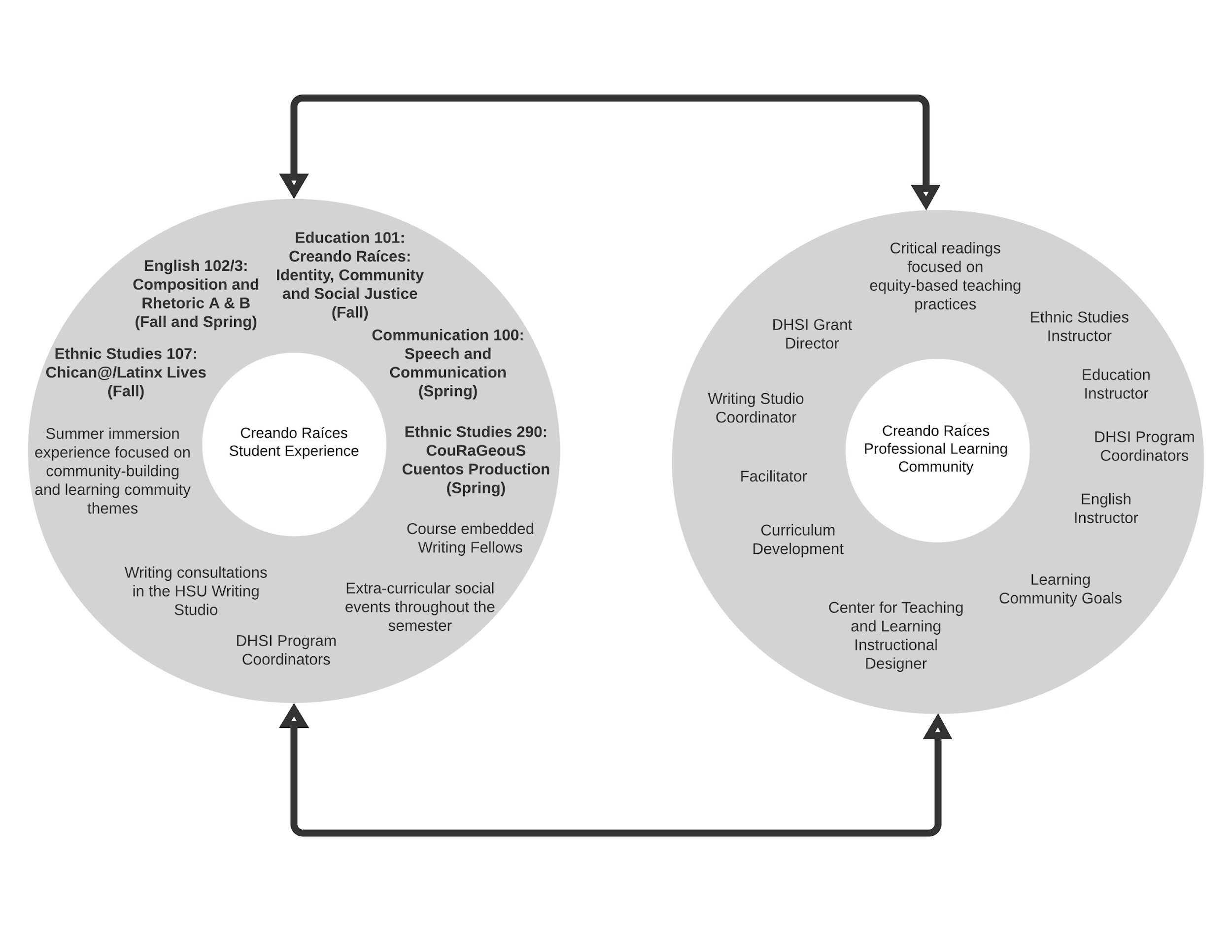

HSU offers various place-based learning communities to first-year students. These communities include linked general education courses, co-curricular community experiences before the fall semester, and a “place-based” local lens to study broader social, political and cultural contexts and applications for learning (Johnson et al.). The Creando Raíces (CR) learning community is a major component of a large Developing Hispanic-Serving Institutions grant received by the HSU School of Education in Fall 2018 (raices.humboldt.edu). As part of the grant’s implementation, coordination of the CR learning community component includes developing supports for first-generation multilingual students during their first year of college via curricular, academic, structural and co-curricular designs. Approximately twenty-five students were recruited to CR for the launch of the program in Fall 2019; the initial cohort of students were predominantly first-generation, Latinx students of color. As part of the CR design, students’ linked courses during their first year focused on explorations of identity, family, community, migration, social justice, education, community organizing, and writing as a tool of empowerment. CR is a unique learning community at HSU because its design includes integrated professional and academic supports, such as: collaborative development through a professional learning community (PLC); an embedded writing fellows component; and direct partnerships with HSU’s Ethnic Studies program and Courageous Cuentos: A Journal of Counternarratives publication. The figure below shows the interactions of these components with the students’ first-year experience in CR.

Figure 1. The Creando Raíces First-year Learning Community Model

Figure 1 is a visual representation of the components that inform the CR model, which we unpack and theorize here. The linked courses in the CR model are bolded in the left circle; each of these courses had at least one embedded writing fellow. The arrows in the figure represent an important facet of our work; as we collaborated to design, implement, and reflect on the first-year experiences of the CR cohort, we also engaged in personal and professional transformations. In other words, the new knowledge that we gained through working and reading together remixed and transformed our prior conceptions of language, multilingual students’ school experiences, and post-secondary institutional systems, which then re-informed the ways we thought about and iterated on the CR design.

In the sections that follow, we present sketches of five linked curricular and professional components of the Creando Raíces (CR) first-year learning community, also captured in Figure 1. These include: two sequenced Ethnic Studies courses; an Education 101 course; a two-semester “stretch” composition course; an embedded writing fellows model; and the professional learning community (PLC) where the co-authors worked together to theorize and develop curriculum. Across these components and anchored by the PLC, we linked explorations of language and discourse to Ethnic Studies, social justice, and writing transfer frameworks. In this profile, we specifically focus on the connections we made between Alim and Paris’ Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies and constructions of writing knowledge transfer.

Integrating Frameworks: Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies and Knowledge Transfer

Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies (CSP) are defined as pedagogies that help culturally and linguistically diverse students develop and maintain cultural competence and academic success while simultaneously developing their (and our) critical consciousness (Puzio et al.). Freire defines critical consciousness as the ability or agency to “intervene in reality in order to change it” (4). Like Alim and Paris, we deliberately use the plural form pedagogies in order to honor and invite multiple teaching approaches, but we also aim to remain grounded in the anchoring concept for CSP: “to seek to perpetuate and foster—to sustain—linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of schooling for positive social transformation” (Alim & Paris 1, our emphasis). As we studied and applied CSP to the Creando Raíces learning community model, we noted that the verb sustain helped us to critique and interrogate a belief we had about teaching and learning: our students should be able to transfer the knowledge they gain in our courses as they move across contexts. However, while knowledge transfer is an important goal of teaching and learning, we wondered about which (or whose) knowledges are the focus of any transfer-oriented pedagogy, and which (or whose) knowledges are sustained or erased.

Theories of writing transfer typically concern how writing knowledge is drawn upon and transformed by writers as they move across distinct situations. Various frameworks for understanding writing transfer argue that it is always shaped by highly specific ecological and/or contextual factors, such as space, power dynamics, and discourse (e.g. Beaufort, Moore; Perkins and Salomon Cognitive Skills; Wardle Creative Repurposing). Similarly, there is broad research on writing transfer that connects individuals’ development of writing knowledge across time to learning situations outside of school (see: Roozen and Erikson). But only very recent scholarship has explored the connections between transfer and multilingualism and multiliteracies (Leonard and Nowacek). Additionally, writing transfer pedagogies aimed at successful transfer have not yet described the extent to which teaching for it values or draws upon underrepresented students’ ways of knowing and being, particularly as these concern non-dominant linguistic knowledges as part of writing development. This gap underscores not only that we need to know more about what it means to transfer writing knowledge in relationship to language, but also that we may be missing an opportunity to develop all students’ (including monolingual English speakers’) critical consciousness of the language practices that they are asked to use or deny in school.

In our initial conversations to develop the writing curriculum of the CR model, we began to see the pedagogical act of developing writing knowledge via a transfer framework as inevitably situated in dominant white academic structures. CSP provided an anchoring point in our development of an alternate and disruptive curricular model that would privilege, center and aim to sustain the diverse literacies, experiences, and knowledges of multilingual students and students of color.

Developing Commitments: The Creando Raíces Professional Learning Community

During the spring semester before the fall 2019 launch of the CR learning community, we worked together as an interdisciplinary professional learning community (PLC) to discuss and design the goals and components of the CR first-year experience. This work is iterative and, as of the publishing of this profile, we have completed our third consecutive semester as a PLC. The membership of this group shifts a bit each semester, but currently includes the authors of this profile. Of the six of us, five of us identify as cis-gender female; one of us is non-binary. Three of us identify as queer. Three of us were the first in our families to attend college. One identifies as Latinx, another as multiracial. One identifies as trans. One of us is a part-time lecturer. Two hold staff positions. Our mix of race, gender, and professional identifications across this group inform our individual and collective perspectives in this article, our ways of knowing and being.

Common purposes of PLCs are to co-construct knowledge, share ideas and resources, and develop connections as scholar-educators (See: Hord and Tobia; Marsh, et al; Stewart). Lisa served as facilitator of the PLC and organized meetings around collectively constructed agendas. She asked the group to read about and take inspiration from Critical Friends Groups (CFGs), which use protocols to engage collective and co-constructive thinking around educational dilemmas or complexities (Dunne, Nave, and Lewis; Curlette and Granville; Moore and Carter-Hicks; and Fahey and Ippolito). Discussions in CFGs take place as facilitated conversations, where protocols guide group feedback. Moore and Carter-Hicks, for example, reported on the transformative value of participating in CFGs over two years in a faculty group in the college of education at their institution. They note that “learning from authentic work in community is the foundation of Critical Friends Groups” (4).

During our first meetings as a PLC, we used the Affinity Mapping protocol to make visible our individual aims of participating in the group and explore alignments or differences across them (for a list of CFG protocols, see: nsrfharmony.org). We worked with two questions: 1) What curricular components, designs, or strategies do you think best facilitate students’ academic success and/or holistic well-being? And 2) What are the dispositions that faculty and staff (we) need to bring to the work that moves students toward success and well-being? The affinity mapping process led us to develop a living document of commitments that we return to repeatedly in order to assess our work as a collective. Because we return to and revise our commitments to reflect our learning, they have become increasingly robust. Our first commitment (of five), for example, sets the tone of our work:

We are committed to individually and collectively approaching this work (engagement in the PLC; design of CR) through cultural humility. We define cultural humility as the act of accepting our limitations. In practicing cultural humility, we work to increase self-awareness of our own biases and perceptions. This is especially important for those of us who come from (white or economic) privilege or who have had opportunities or recognition because of or through the dominant narrative (Garcia, 2019). We commit to engaging in life-long self-reflection to determine and transform any values and attitudes that might keep us from learning from each other and our students.

As we developed curriculum, we read and discussed various texts that explore the decolonization of educational systems, anti-oppressive teaching, and multilingualism, including Alim and Paris’ Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies (CSP), Gina Garcia’s Decolonizing Hispanic-Serving Institutions: A Framework for Organizing, and Asao Inoue’s assessment frameworks outlined in Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies. We put these texts into conversations with readings and conversations about knowledge transfer and learning, such as Perkins and Salomon’s Knowledge to Go: A Motivational and Dispositional View of Transfer. Our discussions in the PLC led us to collectively and individually consider and respond to challenges presented to us by attempting to develop an antiracist, anti-oppressive program that helps multilingual, mulitliterate students transfer their ways of knowing into and within a hegemonic institutional context, the place where students learn and where we work.

Creando Raíces in Ethnic Studies: Counternarratives as Sites of Resistance

An important antiracist anchor of the CR curriculum is a two-semester sequence of Ethnic Studies courses. These courses invite students to enact their embodied knowledges as a way to engage a multilingual, decolonial praxis within our predominantly white HSI. Students in Creando Raíces enrolled in a Chican@/Latinx Lives course their first semester, followed in the subsequent semester by a student journal production course titled Courageous Cuentos: A Journal of Counternarratives; Nancy is the instructor of each of these courses.

The interdisciplinary nature of Ethnic Studies allows for students’ stories to be theorized and elevated as integral forces to dismantling structural inequalities and oppression.

Nancy’s courses draw necessary attention to the ways epistemic violence gets reproduced within Western, traditional disciplines (Elia et al). Her assignments asked students to explore and write personal histories that became valuable counternarratives to institutional, social inequalities. To ensure that students’ conversations remained critical, these subverted histories were coupled with theoretical frameworks that helped them further understand colonialism, nation-states, borders, migration, and the transnational experience within diverse Latinx, indigenous communities. These frameworks include Chicana feminist theory, indigenous epistemologies, queer of color critique, and theories that address social movements and the simultaneity and ongoing fluidity of borders and the immigrant experience. Such interdisciplinary, theoretical perspectives offered CR students tools and language to be able to identify and articulate complex social problems that directly impact them and their families.

For most CR students, the Chican@/Latinx Lives course was the first time they read texts from scholars of color who come from their communities. Students’ personal narratives were critically examined next to scholarly texts, and students’ stories became political; their desires to further explore and discuss lived experiences of racial, sexual, and gender discrimination emerged. Nancy placed these discussions around themes of identity, home, family, migration, and community in the context of social justice, and as students wrote and presented their narratives, they meshed their prior knowledge-as-narrative with the critical frameworks in the academic space. This type of narrative work is central to the practice of culturally sustaining pedagogies because it fosters opportunities for students to listen and respond critically, but also build community and work collectively in meaningful ways to integrate their linguistic and cultural epistemologies into their learning.

The themes of the Chican@/Latinx Lives course also encourage students to engage in critical conversations that examine power dynamics in and across HSU’s communities, classrooms, and institutional spaces, including the ways that dominant and non-dominant languages are used or valued. The ability to cross-language during class discussions and in response to formal and informal writing assignments opens space for students to compose across languages (primarily English and Spanish). Code-switching oftentimes took place in this course, and in some cases, students felt comfortable enough to submit entire assignments in a language other than English. Because Nancy is bilingual, she was able to provide feedback to Spanish-speaking students in Spanish; this allowed her to engage with all students in ways that honored their existing linguistic knowledge and gave them permission to transfer linguistic knowledge into the classroom space in ways that would help them learn. At the close of the Chican@/Latinx Lives course, students commented “I feel seen;” “I feel at home here” and “This class is what I needed.” CR students saw the potential these stories had to counter the erasure and silencing of their voices and experiences both on campus and in the local community. They reflected a genuine gratitude towards the topics and readings that centered their embodied, lived experiences as students of color in a predominantly white university. Students also began to understand how their stories can be transferred into academic space and used as a source of empowerment and social change; they learned that their stories should never be denied or erased but rather drawn upon to enrich their learning experience.

In the spring semester, students explored the potential of their stories as counternarratives to dominant discourses in a journal production class where they were invited (but not required) to publish their writing from their Chican@/Latinx Lives course in Courageous Cuentos: A Journal of Counternarratives, published annually by the Department of Critical Race, Gender & Sexuality Studies (digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/courageouscuentos/). The journal was initially developed by students who wanted to illustrate the power that came with telling their stories in their own languages and under their own terms—uncensored, multilingual, and with unflinching candor. With guidance from their professor, each spring students collectively edit submissions and curate the volume under a central theme that connects to their social justice work both on campus and in their local communities. The journal—and the opportunity to engage in publishing work—is another example of how students were invited to transfer knowledge into an academic space in a way that transcends the boundaries of dominant discourse and therefore disrupts it.

The social-political context of where HSU is geographically located and its designation as an HSI informs the unique experiences of multilingual students and/or students of color that historically link them to multiple struggles against power in occupied Wiyot land. The institution’s inability to effectively serve all students, as students in Nancy’s courses often expressed in their writing, is an indicator of the colonial legacies of racism still embedded at HSU. As one student noted, “HSU is a predominantly white space so it is important to acknowledge the hardships that have been overcome to get to HSU and to celebrate the journeys of those who are here” (Sanchez). Another student argued that “These counternarratives are crucial to breaking down barriers and empowering community building in Humboldt County and beyond” (Lopez). CR students have permission to sustain and value their ways of knowing as part of their academic learning in our program. In the CR Ethnic Studies courses, this occurred when students presented narratives that countered dominant ones, when they saw that their narratives are ways of knowing that have political and social power. Students’ counternarratives resonate with what Garcia (2019) argues is a decolonial vision. This vision works towards the advancement of knowledge, histories, languages, and epistemologies that allow the stakeholders of the post-secondary institution to reimagine long-held and deeply systematized structures for learning, to move beyond simply prioritizing measurable outcomes and toward socially just models for education.

Social Justice in the Composition Classroom through Anti-Racist Writing Assessment

In Natalie’s two-semester “stretch” composition course, moving beyond measurable outcomes and toward antiracist assessment methods were foregrounded as a way to explore writing development. In his introduction to Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future, Inoue asks: “How does a teacher not only do no harm through his writing assessments, but promote social justice and equality?”(3). Inoue’s question and the important claims of his work respond to scholarship on institutionalized modes of writing assessment as evaluation; these have been analyzed in numerous research studies as harmful, oppressive and worthy of critique (Burns, Cream, and Dougherty; Inoue and Poe; Lamos). In the composition course, Natalie invited CR students to reimagine writing assessment through a decolonized, anti-oppressive framework, which included exploring how their writer identities are intersectional.

One of Natalie’s major assignments asked students to take on a “writing researcher” identity and study, through primary and secondary research, how communities and groups use texts and how the discourses of these groups are embedded in particular histories, cultures and ideologies. This assignment challenged students to explore writing situations “...matter-of-factly with the knowledge that...languages, literacy histories and cultural ways of being...are not pathological”(Alim and Paris 2, our emphasis). This assignment helped students to disrupt myths of writing, such as that English represents “good” writing always, or that good writers are “naturally good.” In Natalie’s class, CR students studied discourse theory, explored dominant and non-dominant literacies, and discussed the ways that race and class shape access to writing-in-community. For example, students read from Anzaldúa’s How to Tame a Wild Tongue and bell hook’s Keeping Close to Home in order to consider the links between language and identity, and how white language supremacy often acts as a gatekeeping mechanism within educational institutions to differentiate English-fluent students from students who have multi-linguistic fluencies. (Students also re-read and discussed these authors in both Libbi’s and Nancy’s classes.) Similarly, through discussions that drew upon the work of Vershawn Young and James Paul Gee, students critiqued notions of “good” academic writing, linked power to the mono-linguistic texts of dominant social and racial groups, and began to understand the ways that linguistic knowledges are not treated equally in academia.

In addition to the ways that CR students engaged in research about discourse and writing assessment as social practices, they were also able to explore assessment and feedback through studying their own and each other’s labor as writers. Within a labor-based assessment system, students choose the types of assignments they complete and the time-based effort that corresponds to them; the choices that students make correspond to a final grade in the course (Inoue). Natalie’s expectations for the labor and time students put into the class were high; for example, in order to earn a B in the course, the contract required students to attend 85% of classes and complete all reading and writing assignments. In this system, students’ grades were not contingent on their ability to assimilate or perform dominant white discourses. Instead, students had control over their labor in the course in relationship to their preferred final course grade; every passing grade was accessible to every student. Natalie’s contract grading reflects the decolonial model that CSP proposes, arguing that “[a]ntiracist writing assessment ecologies, at their core (re)create places for sustainable learning and living” (Inoue 14). A labor-based contract invites students to experiment and make mistakes without the fear and anxiety of punishment that unclear or unfair grading practices can create; instead, students can discuss their rhetorical (including linguistic) choices with each other and their instructor in terms of purpose and effect. Labor-based assessment also de-emphasizes an adherence to Standard Academic English (SAE) and instead allows students to take discoursal and linguistic risks as connected to making meaning in rhetorical and academic spaces.

Because their grade in the composition course was not based on adherence SAE, CR students were excited by the possibilities of transferring non-dominant, non-English and/or nonwhite language practices into their written work. In an act of resistance to dominant discourse, for example, one student began their research paper with the line “Here’s the fucking facts.” As they did in their Ethnic Studies courses, some students experimented with Spanish and English in the same text. As students read about and researched writing assessment, they transferred their prior knowledge and experiences of being assessed as writers into these discussions, often landing on new understandings of the ways that writing assessment and grading are mechanisms for enforcing SAE/white language supremacy. As writing researchers, students also used their emerging understandings of discourse and assessment to study the membership-granting practices of the communities they studied.

During PLC discussions, Natalie shared the rich work students created in the course with the group. We hoped that CR students would be able to transfer their emerging critical knowledges of language beyond the course as they continued to navigate institutional assessment systems; we wondered how they might identify, study, and/or resist oppressive writing assessment practices and/or language expectations in subsequent classes and communities, particularly as these concern SAE, gatekeeping, and linguistic knowledge.

However, we also continued to grapple with some worrisome complexities of engaging students in these ways. There isn’t only the risk of a poor grade if students remix their writing to include nondominant discourses or languages. There is also the risk of not passing a course and/or affecting their relationships with professors if they use “Here’s the fucking facts” in a research paper. Most important for us to acknowledge was that there is also a serious risk of students exposing themselves to danger and violence, including micro- and macroaggressions. This caution is one we return to in our conversations in the PLC; considering it helps us to think more critically about how we talk about the transfer -- and transformation-- of writing knowledge to include a plurality of our students’ epistemologies, languages, and experiences, and it helps us to think about how we might work within our institution to facilitate the necessary structural changes that will support this type of resistance to and transformation of linguistic gatekeeping. Otherwise, as is perhaps the case in the examples of student writing we’ve shared so far, we are asking our most vulnerable students to do the work of transformation for us. At our institution, faculty and staff need to do a better job of explicitly valuing all students’ languages and voices through structural change instead of putting this burden on them.

Exploring Transfer through Identity, Community and Social Justice

Still, we were doing some things that were working. CR students told us in formal and informal reflections that they had never thought about learning, language, writing, or their educations in these ways before, including in Libbi’s general education class, which is designed to meet HSU’s institutional outcome of “lifelong learning and self-development.” Libbi’s curriculum constellated with Nancy’s and Natalie’s to ask students to examine institutional structures and the possibilities of structural change. Students explored frameworks for community building, developing professional goals, and engaging multicultural perspectives as part of academic and self-development. CR students continued to study intersectionality, institutional discourses, and self-advocacy, and they centered these ideas around themes of identity, community, and college success.

Students began the semester by exploring the theme of identity. Through class activities, discussions and readings, students examined their multiple identities from a funds of knowledge perspective which recognizes the collection of knowledges that students bring with them from their homes and communities (Moll et al.). As an explicit exploration of the Creando Raíces name and in order to connect to the work they were doing in Nancy’s course, students articulated the family and community roots they carried with them to HSU and described how these roots were re-established or changed as they transitioned to the university. The students wrote “I am” statements and name poems, which they shared with other CR members, and (in connection to the Ethnic Studies courses) they read poetry and prose from Courageous Cuentos in order to explore and legitimize multiple experiences, genres and authors. Libbi also shared various texts in the picture book genre with students which highlighted narratives that affirm non-white identities and experiences; the picture books helped to visually illustrate theories such as intersectionality and connect emotions to learning (Denise; hooks; Martinez-Neal; Mendez).

In order to support the development of students’ critical consciousness (Freire 36), Libbi worked with students to deconstruct different ways that various identities appear in the university setting. CR students explored the extent to which their home values, languages and assets were or were not made visible on campus. CR students applied their developing understandings of identity as a lens to re-read and -conceptualize Anzaldúa and hooks, and they created texts that explored and explained the concept of identity and roots through a reflective process that included choosing from a range of modalities including written text, slide presentation, screencast or webcast, artistic reflection (drawing, poem, vignette, etc.), or other student-identified formats. Students produced work across these options, such as paintings with written descriptions, journal entries, and video reflections. These products allowed students to transfer their linguistic and cultural knowledges into their compositions in ways that expanded and diverged from typical academic constructions of textual production and which drew upon students’ knowledges of text in order to theorize identity.

Like Natalie’s course, assessment was informed by Inoue’s antiracist heuristic for learning (283). While Libbi did not explicitly use the labor-based model that was implemented in the composition course, she drew upon it as a framework for reflecting and revising previously established approaches to assessment. Libbi focused on Inoue’s ecological assessment themes of power and people by discussing writing (and other forms of) assessment and feedback by working with CR students to question who holds the power in assessment processes, how students might engage in developing assessment criteria themselves, and what it meant in terms of power to revise their written work. In this way, students engaged in lateral transfer, moving their understandings about discourse and assessment across courses, and reinforcing these concepts as malleable frameworks that can be critiqued through participation and/or resistance.

Meanwhile, in the PLC, Inoue’s framework for assessment made us highly aware of our own power—not only because it makes visible the ways that students perceive and project power onto the instructor’s positionality as an evaluator, but also of how we were situated (and evaluated) in the institutional hierarchy. By using the lenses of CSP, antiracist assessment, and Garcia’s call to decolonize the HSI, we gained language and frameworks with which we could begin to disrupt and/or reimagine established conceptualizations of teaching, assessment and learning. For example, in spring of 2020, Lisa facilitated an interdisciplinary teaching symposium titled Equitable Approaches to Teaching and Assessing Writing where a faculty group studied and experimented with labor-based grading approaches to reimagine (and decolonize) their prior assessment practices in their disciplinary contexts. In these ways, the question of “Who holds power?” in the classroom and institution continues to anchor the social justice foundations of the CR model.

Disrupting Dominant Discourses Inside and Outside the Classroom: Developing a Critical, Decolonized Writing Fellows Program

Outside of the classroom, power also informed how we thought about academic and social supports for CR students, including how the integration of peer writing consultants might work to distribute authority within a decolonized framework. In partnership with the DHSI grant, HSU’s Writing Studio (our university-wide writing center) piloted an embedded writing fellows program in the Creando Raíces learning community during the 2019 - 2020 academic year. Using the theoretical foundations from the PLC and broader grant goals, the writing fellows program aims to align pedagogies between academic support programs and classrooms (Corbett; Spigelman and Grobman) and legitimize language diversity through peer-to-peer modeling (Garcia). While writing centers can decenter classroom authority and create opportunities for meaningful, peer-to-peer learning, they can also act as institutional gatekeepers that reinforce racist language norms, especially for multilingual writers (Greenfield and Rowan; Villanueva; Bawarshi and Pelkowski; Grimm). By positioning multilingual students as sources of writing knowledge within a curriculum that strives to validate and sustain multilingual literacies, this program seeks to decenter and de-stabilize dominant discourses of whiteness and authority, while simultaneously centralizing the diverse literacies, experiences, and knowledges students bring to HSU.

When planning the program, we envisioned the CR writing fellows as experienced students who would support the learning community cohort in their three linked courses by participating in classes and meeting with students in the Writing Studio. We outlined the fellows’ roles in three ways: as consultants who help CR students develop as writers, readers, and critical thinkers; as model scholars who demonstrate successful learning strategies and behaviors; and as collaborators who work with the instructors on learning objectives while helping build a personal connection to the course material and the campus community. With this vision and the goals of CR in mind (and as made explicit in our job announcement), we hired two fellows in August 2019; both were first-generation college students and fluent in English and Spanish. Both connected to the CR learning community imperative, saying that they wished such a program had existed when they were first-year students.

Jessica and Corrina facilitated a pre-semester training for the fellows that included discussing the readings that Nancy, Natalie, and Libbi would assign in their courses. This early training allowed the fellows to explore the concepts that students would engage as members of the CR learning community: intersectional identities, language usage, discourse, and the power structures that govern them. One fellow reported that the trainings and coursework helped her see writing processes as “personal” and “identity-based” (Year 1 Fellows), which in turn shaped her approach to peer consultations: rather than find what’s “wrong” with a text, she focused on helping writers determine how and if they were reaching their rhetorical goals. The other fellow explained that working within the CR curriculum helped her “unlearn” previous beliefs about literacy, saying, “I learned [...] that there is no one correct way to write. I had heard of this before but had never really believed it” (Year 1 Fellows). Over the course of the fall semester, the fellows observed the CR students move from anxiety about receiving feedback to expressing more ownership over their writing: “the first time they came with their essay shaking in their hands, very timid, very afraid to ask any questions. And as the semester progressed, [they] became more and more confident [...] They had more agency over the things that they wrote” (Year 1 Fellows). Our fellows’ shifts in thinking and the CR students’ shifts in dispositions toward their writing suggest that our program's focus on Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies pushed their thinking away from a deficit model of learning (“this is wrong”) toward a critical consciousness model (“does this meet your rhetorical goal?”). These shifts, which echo antiracist assessment, allowed fellows to focus on writers’ “thinking and learning” rather than on finished products.

Through individual meetings, the fellows helped CR students apply this emerging critical consciousness to their understandings of what constitutes academic writing. In observed sessions, the fellows and CR students engaged in “transfer talk” that encouraged the repurposing of personal knowledge and linguistic practices often suppressed in other writing contexts. Nowacek et al. define writing center transfer talk, in part, as “the talk through which individuals make visible their prior learning,” particularly in conversations about writing in progress (Nowacek et al). Many CR assignments asked students to draw on their personal histories and backgrounds. In their conversations, the fellows and the students voiced a shared understanding that these stories mattered, recognizing, as one fellow put it, that students “come with different things to the table” and these differences should be “appreciat[ed]” and “valu[ed]” (Year 1 Fellows). Preliminary observations of writing consultations suggested that, when discussing writing-in-progress, the fellows reaffirmed the knowledge multilingual writers (CR students) brought to their texts and guided them through the process of repurposing this knowledge in the academic context.

As Nowacek et al. note, writing center transfer talk also involves “try[ing] to access the prior learning of someone else.” In observed sessions, our fellows elicited knowledge from the writers, but the writers also elicited knowledge from the fellows. The fellows shared similar backgrounds and educational experiences as many of the students: “I was you. [...] A few years ago, I was the only person of color in some of my classes” (Year 1 Fellows). This connection and relationship development allowed for frequent “co-construction” exchanges where fellow and student “collaboratively develop[ed] a strategy for understanding” (Nowacek et al.). Other assignments, such as the discourse community research project in Natalie’s course and the counternarratives project in Nancy’s, created opportunities for the fellows to discuss more explicitly how they, as scholars and community members, had negotiated power dynamics around discourses at HSU.

The fellows also played a role in what Nancy and Natalie described as linguistic freedom and flexibility afforded by integrating multilingual writing, speaking, and communication into CR classrooms. Fellows were encouraged to use English and Spanish as appropriate when meeting individually with CR students, commenting on drafts and contributing to class discussion. In this way, they modeled cross-languaging and code-meshing within institutional spaces, challenging the traditional “SAE only” discourse of classrooms, the Writing Studio, and the post-secondary institution.

Like any new endeavor to connect the classroom with academic support programs, this writing fellows program relies on intentional and sustained relationship-building. This past year revealed the importance of guiding faculty in establishing fellows’ roles in their classes and setting up regular meetings. Facilitating these connections meant encouraging instructors to develop clear expectations for how students can interact with the fellows, such as including fellows in peer review sessions or asking students to participate in a consultation with a fellow as part of a labor-based grade. Furthermore, if we expect fellows to model cross-languaging in the classroom, ongoing training needs to include readings and discussions related to the risks and benefits of linguistic boundary-crossing in university settings.

The writing fellows program is expected to grow with the grant: In 2020-2021, fellows will be placed in Creando Raíces and in a new HSI learning community, Teachers 4 Social Justice. By drawing fellows from the Writing Studio, we see this program as one step toward spreading Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies and multilingual academic writing practices beyond the CR learning community.

Transforming Our Students, Transforming Our Selves: Some Applications and Two Cautions

Our collaborative efforts to integrate curriculum, academic support, and professional learning in the PLC led to deep, transformational experiences of learning—for us as well as for our students. By engaging Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies, antiracist assessment, and decolonial praxis in the CR model, and by exploring what it means to transfer writing and linguistic knowledge into, across, and beyond school-based contexts, we have been able to consciously help our students—and help ourselves—foster knowledge transfer in ways that center and sustain diverse cultural and linguistic ways of knowing. These frameworks, we argue, can help to transform oppressive educational systems and dismantle white supremacy in them.

A caution: We are not arguing here that white academic discourse should not be taught in the writing classroom, but that it should be taught and studied as a discourse, one that is objectively identified, and, like all discourses, viewed as a particular type of linguistic knowledge that evolves as it simultaneously enacts the values and beliefs of those who use it. A CSP approach to writing transfer acknowledges that writers bring prior knowledges into every rhetorical situation and that our prior knowledges are inseparable from our beliefs, values, identities, languages, discourses, and cultural ways of knowing. We can study discourse and language critically with our students, in ways that honor what they know and how they learn, and which allow them to make choices about how to use language to foster change. This approach to the teaching of writing is one step toward the decolonization and transformation of existing constructions of linguistic capital.

A second caution: While we offer some potential applications that engage the connections between CSP and writing transfer, we advise against any prescriptive approach and instead emphasize the importance of acknowledging localized institutional, classroom and community contexts as inseparable from pedagogical action and systemic change. With this second caution in mind, we offer suggestions for the writing classroom from our own work in CR:

-

Conscious development of texts (syllabi, assignments) that affirm and privilege students’ knowledges (not only academic) and show how these knowledges integrate with and can transfer into content/conceptual knowledge about writing.

-

Lessons which explicitly build on what students already know and are clear about what we want them to achieve, including a critical consciousness of learning and transferring knowledge into and out of dominant structures or discourses.

-

Assignments that ask students to analyze and critique the ways discourse works in and across communities, rhetorical situations, and genres.

-

Development of a broad representation of texts, authors, and viewpoints, including counter viewpoints, that are in conversation about critical concepts such as multilingualism, multiliteracies, code-meshing/switching, textual production, and discourse.

-

Development of classroom norms and expectations in collaboration with students that include assessment and evaluation, while inviting students to develop similar expectations for the instructor.

By holding up CSP as a lens for understanding writing transfer, we have been consistently reminded that white discourse has been hegemonized as academic discourse. Yet a danger of centering white academic discourse as how we should write in school is that its assimilation systematically erases the cultural and linguistic knowledges that multilingual students and students of color bring to and might write with and about in the classroom. The consequences of such erasure are already everywhere we look. Alim and Paris suggest that Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies can exist “wherever education sustains the lifeways of communities who have been and continue to be damaged and erased through schooling” (1). As we have explored in the CR program and in writing this profile, these lifeways, if critically and consciously sustained, not only help to transform the discourses they have been asked to learn and perform, but enact racial and linguistic justice. Specifically, culturally sustained knowledges help teachers and students know better how to use writing and communication to address and resist systemic oppression. While we have much more to do as we continue to build and revise the Creando Raíces program’s components and structures, this work has allowed us to come together as collaborators and allies to (re)imagine what writing development and writing knowledge transfer can look like in anti-oppressive, decolonized educational spaces.

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. How to Tame a Wild Tongue. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Anne Lute Books, 1987, pp. 75-86.

Alim, H. Samy, & Django Paris. What is Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies and Why Does It Matter? Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World, edited by Django Paris and H. Samy Alim, Teachers College Press, 2017, pp. 1-21.

Bawarshi, Anis and Stephanie Pelkowski. Postcolonialism and the Idea of a Writing Center. The Writing Center Journal, vol. 19, no. 2, 1999, pp. 41-58.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State University Press, 2007.

CouRaGeouS Cuentos: Volume 3 (2019). Courageous Cuentos: A Journal of Counternarratives, Humboldt State University, https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/courageouscuentos/.

Corbett, Steven J. Beyond Dichotomy: Synergizing Writing Center and Classroom Pedagogies. The WAC Clearinghouse, 2015.

Curlette, William L., and Harley G. Granville. The Four Crucial Cs in Critical Friends Groups. The Journal of Individual Psychology, vol. 70, no. 1, 2014, pp. 21-30.

Denise, Anika Aldamuy. Planting Stories: The Life of Librarian and Storyteller Pura Belpré. Harper Collins, 2019.

Dunne, Faith, Bill Nave, and Anne Lewis. Critical Friends Groups: Teachers Helping Teachers to Improve Student Learning. Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 28, no. 4, 2000, pp. 31-37.

Elia, N., Hernández, D., Kim, J. et al. Introduction: A Sightline Critical Ethnic Studies: A Reader, edited by Rodríguez, et al., Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Fahey, Kevin, and Jacy Ippolito. Variations on a Theme: As Needs Change, New Models of Critical Friends Groups Emerge. Journal of Staff Development, vol. 36, no. 4, 2015, pp. 48-52.

Freire, Paulo. Education for Critical Consciousness. Bloomsbury Publishing, 1973.

Garcia, Gina Ann. Decolonizing Hispanic-Serving Institutions: A Framework for Organizing. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, vol. 17, no. 2, 2018, pp. 132-47.

Gee, James Paul. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. Routledge, 2014.

Greenfield, Laura and Karen Rowan, editors. Writing Centers and the New Racism: A Call for Sustainable Dialogue and Change. 3rd ed., Utah State University Press, 2011.

Grimm, Nancy Maloney. Good Intentions: Writing Center Work for Postmodern Times. Boynton/Cook-Heinemann, 1999.

hooks, bell. Keeping Close to Home: Class and Education. Working-Class Women in the Academy, edited by Michelle M. Tokarczyk, University of Massachusetts Press, 1993, pp. 99-111.

hooks, bell, and Christopher Raschka. Skin Again. Disney/Jump at the Sun, 2017.

Hord, Shirley M., and Edward F. Tobia. Reclaiming our Teaching Profession: The Power of Educators Learning in Community. Teachers College Press, 2015.

Inoue, Asao B. Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future. WAC Clearinghouse, 2015.

Johnson, Matthew, Amy Sprowles, Katlin Overeem, and Angela Rich. A place-based Learning Community: Klamath Connection at Humboldt State University. Learning Communities Research and Practice, vol 5, no 2, 2017.

Leonard, Rebecca Lorimer, and Rebecca Nowacek. Transfer and Translingualism. College English, vol. 78, no. 3, 2016, pp. 258-264.

Lopez, Marí. Why Courageous Cuentos? Courageous Cuentos: A Journal of Counternarratives, vol. 3, 2019, p. Vii.

Marsh, Julie A., Melanie Bertrand, and Alice Huguet. Using Data to Alter Instructional Practice: The Mediating Role of Coaches and Professional Learning Communities. Teachers College Record, vol. 117, no.4, 2015, pp. 1-40.

Martinez-Neal, Juana. Alma and How She Got Her Name. Candlewick, 2018.

Mendez, Yamila Saied. Where Are You From? Harper Collins, 2019.

Moll, Luis and Cathy Amanti, Deborah Neff & Norma Gonzalez, N. Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms. Theory into practice, vol. 31, no. 2, 1992, pp. 132-141.

Moore Jessie. Mapping the Questions: The State of Writing-related Transfer Research. Composition Forum, Fall 2012. http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/map-questions-transfer research.php. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

Moore, Julie A., and Joya Carter-Hicks. Let’s Talk! Facilitating a Faculty Learning Community Using a Critical Friends Group Approach. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, vol. 8, no. 2, 2014, pp. 1-17.

Nowacek, Rebecca S., et al. '‘Transfer Talk’ in Talk about Writing in Progress: Two Propositions about Transfer of Learning. Composition Forum, vol. 42, 2019, https://compositionforum.com/issue/42/transfer-talk.php.

Perkins, David. N. & Gavriel Salomon. Are Cognitive Skills Context-Bound? Educational Researcher, vol. 18, no. 1, 1989, pp. 16-25.

Perkins, David. N. & Gavriel Salomon. Knowledge to Go: A Motivational and Dispositional View of Transfer. Educational Psychologist, vol. 47, no. 3, 2012, pp. 248-258.

Puzio, Kelly, Sarah Newcomer, Kristen Pratt, Kate McNeely, Michelle Jacobs, & Samantha Hooker Creative Failures in Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy. Language Arts, vol. 94, no. 4, 2017, pp. 223-233.

Roozen, Kevin Roger, and Joe Erickson. Expanding Literate Landscapes: Persons, Practices and Sociohistoric Perspectives of Disciplinary Development. Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2017.

Sanchez, Mayra. Why Courageous Cuentos? Courageous Cuentos: A Journal of Counternarratives, vol. 3, 2019, p. vii.

Spigelman, Candace and Laurie Grobman, eds. On Location: Theory and Practice in Classroom-Based Writing Tutoring, USU Press Publications,2005.

Stewart, Chelsea. Transforming Professional Development to Professional Learning. Journal of Adult Education, vol. 43, no. 1, 2014, pp. 28-33.

Villanueva, Victor. Blind: Talking about the New Racism. The Writing Center Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, 2006, pp. 3-19.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Creative Repurposing for Expansive learning: Considering ‘Problem-exploring’ and ‘Answer-getting’ Dispositions in Individuals and Fields. Composition Forum, Fall 2012. http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/map-questions-transfer-research.php. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

Wardle, E. & Downs, D. Writing about Writing: A College Reader (3rd edition), Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2014.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. Code-meshing: The New Way to Do English. Other People’s English: Code-Meshing, Code-Switching, and African American Literacy, 2014, pp. 76-83.

Year 1 Fellows. Focus group interview. Fall 2019, Spring 2020.

Creando Raíces from Composition Forum 44 (Summer 2020)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/44/hsu.php

© Copyright 2020 Lisa Tremain, Jessica Citti, Natalie Giannini, Libbi R. Miller, Nancy Pérez, Corrina Wells.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 44 table of contents.