Composition Forum 42, Fall 2019

http://compositionforum.com/issue/42/

“Transfer Talk” in Talk about Writing in Progress: Two Propositions about Transfer of Learning

Abstract: This article tracks the emergence of the concept of “transfer talk”—a concept distinct from transfer of learning—and teases out the implications of transfer talk for theories of transfer of learning. The concept of transfer talk was developed through a systematic examination of 30 writing center transcripts and is defined as “the talk through which individuals make visible their prior learning (in this case, about writing) or try to access the prior learning of someone else.” In addition to including a taxonomy of transfer talk and analysis of which types occur most often in this set of conferences, this article advances two propositions about the nature of transfer of learning: (1) transfer of learning may have an important social, even collaborative, component and (2) although meta-awareness about writing has long been recognized as valuable for transfer of learning, more automatized knowledge may play an important role as well.

Over a decade ago, David Smit declared that “overwhelmingly the evidence suggests that learners do not necessarily transfer the kinds of knowledge and skills they have learned previously to new tasks” (119) and challenged the field of writing studies to trace out “the implications of what we know about transfer ... for the writing curriculum as a whole and the ways courses relate to or ‘talk to’ one another” (134). Since that time, writing studies scholars have built up a strong foundation of knowledge by analyzing transfer of learning in a variety of contexts, over different time frames, and using different units of analysis. Ten years later, the claim that “university programs can ‘teach for transfer’” is one of the “essential principles of writing transfer” identified in a volume composed by participants in the Elon Seminar on Critical Transitions (Moore 7). We share this optimism—but we also believe that our understandings of transfer of learning might benefit from expanding the contexts in which we study transfer, specifically by focusing our analysis on talk about writing in progress.

This project initially sought, using methods of grounded theory, to analyze conversations about writing in progress in the belief that a new type of data might provide new insights into the phenomenon of transfer of learning. That analytical process led us to develop the idea of transfer talk—and that concept, in turn, led us to interrogate two common assumptions in the theories of transfer of learning within writing studies. Throughout this article, we speculate that transfer of learning is a strikingly social, even collaborative, cognition and we question whether the scholarly emphasis on the value of conceptualized, abstract knowledge has overshadowed the potential importance of less conscious, more automatized connections.

Writing studies scholars have studied transfer of learning in a growing number of sites. Many early studies focused on transfer of knowledge from first-year writing courses (e.g., Bergmann and Zepernick; Wardle Understanding ‘Transfer’; Yancey). Subsequent studies have expanded that focus to include a variety of disciplinary contexts (e.g., Lindenman; Nowacek, Agents; Russell and Yañez) and non-classroom sites such as writing centers (e.g., Bromley et al.; Driscoll; Hill; Hughes et al.). Writing studies scholars have also looked beyond classrooms into workplaces (e.g., Beaufort, Writing in the Real World; Brent; Schieber) and extracurricular writing (e.g., Anson; Fraiberg; Roozen; Rounsaville).

Transfer of learning has also been studied over a variety of different time frames. There is a strong tradition of longitudinal research, following students over several years, often from their first-year writing course through graduation (e.g., Beaufort, College Writing; Carroll; Chiseri-Strater; Herrington and Curtis; McCarthy). Some research has focused on the transition from high school to college (Reiff and Bawarshi) and there is an emerging focus on tracing writers over their lifespan (e.g., Bazerman et al.; Lemke).

Finally, while many of these studies focus on individuals—in the form of case studies, quick anecdotes, and extended ethnographic studies—others have argued for the value of alternate units of analysis. Engeström, for instance, has argued that understanding transfer of learning requires a focus not simply on individuals but on the relationships between the multiple activity systems within which those individuals operate. And a number of scholars—in many cases, inspired by the Elon Seminar on Critical Transitions—have highlighted the value of cross-institutional studies (e.g., Anson and Moore; Driscoll et al.; Moore; Yancey et al.).

However, across all of these different sites, time frames, and units of analysis, researchers have tended to collect and analyze the same types of data: (1) drafts of completed papers and (2) interviews or reflective prompts eliciting retrospective accounts of how those papers were composed and what was learned from those experiences. Rarely have writing studies scholars sought to study transfer of learning during the writing process or examined talk about that writing in progress (see Winzenried et al. for an important exception). This project seeks to fill that gap in our research by analyzing transcripts of conversations about writing in progress generated by writers and peer tutors in a university writing center. We believe that research focused on talk about writing in progress—in this case, research conducted in a writing center—can make a valuable contribution to broader understandings of transfer of learning.

This article both tracks the emergence of the concept of transfer talk—a concept distinct from transfer of learning—and teases out the implications of transfer talk for theories of transfer of learning. Through our analyses of talk about writing in progress, we came to define transfer talk as the talk through which individuals make visible their prior learning (in this case, about writing) or try to access the prior learning of someone else. In our view, this definition is compatible with but goes further than similar definitions offered by Schieber (“how [participants] talked about their own writing” [467]) and Hill (“moments when tutors engaged students in talking about their previous knowledge or in talking about how their current learning connected to future tasks” [85]). Like previous scholars, we understand transfer talk as an opportunity for writers to surface prior learning about writing—but our analyses have led us to emphasize more heavily the potentially collaborative nature of that talk.

To be clear: we are not claiming that instances of transfer talk are evidence that writers have effectively (or even consciously) repurposed knowledge from an earlier context; the instances of transfer talk we documented did not necessarily (in fact, rarely) suggest a richly conceptualized meta-awareness of writing. Instances of transfer talk are simply—but importantly—moments in which prior learning about writing surfaces and becomes (however fleetingly) part of a conversation about the task at hand. In this way, we build on the findings of Jarratt and colleagues who, in describing pedagogical memory, note that talk about writing (in the case of their study, an interview) “generates as much as retrieves knowledge” (49)—an observation that underlines the importance of such talk, but does not claim that it provides evidence of any meta-aware repurposing of knowledge.

Some readers may be troubled by the absence of such meta-awareness in what we are calling “transfer talk;” they might object that talk without such conceptualization may be evidence of learning, but not of transfer of learning and that the term “transfer talk” is thus a misnomer. But such objections rest on the assumption that only intentional deployments of conceptualized understandings of writing should be termed transfer of learning, that the serendipitous or accidental transfer that can result from less abstracted knowledge is not “real” transfer. We anticipated such objections and more than once considered changing our terminology (to, perhaps, “prior knowledge talk” or “transfer-ripe talk”). Nevertheless, we continued with the term “transfer talk” precisely because it challenges the widely held assumption that the sine qua non of learning transfer is the intentional repurposing of conceptual and abstracted knowledge. As we argue in the second of the two propositions we offer, examining the data collected for this study invites a broader conception of transfer of learning that includes more routinized, less intentional connections as well as the types of “deliberate mindful abstraction” more often focused on in the field of writing studies (Perkins and Salomon 25).

Data Collection

This research was conducted within the writing center at Marquette University, a four-year, research-intensive university in the Midwestern United States. The research team consists of a PI (the director of the university writing center, Rebecca) as well as six undergraduate researchers involved in the W.R.I.T.E. Fellows Program (the remaining co-authors of this article).{1}

In order to explore how talk about writing in progress might inform our understanding of transfer of learning, we began by selecting 30 videos from a larger archive of 46 videos that had been gathered by tutors during the 2015-16 academic year as part of an IRB-approved (HR-2504), ongoing effort to reflect on and strengthen our tutoring. From this archive, we initially selected 25 videos using a table of random digits. The last five videos were selected to include a greater number of tutors. Among the 30 selected videos, 21 different tutors (out of a staff of 35) were represented: 17 were undergraduate students and four were graduate students, which is roughly representative of the balance between undergraduate and graduate tutors on staff. Sixteen of the tutors were female and five were male—a slight overrepresentation of the men on our staff at that time. Approximately one-third of the writers brought in projects from the university’s first-year writing course, and five writers sought assistance with a personal statement. The remaining projects included writing from a variety of different courses including literature, history, ethics, nursing, and plant pathology. Five of the 30 writers identified themselves as L2+ students.

Data Analysis

Data analysis proceeded in three stages: transcribing, developing a coding schema, and using that coding schema to analyze all 30 transcripts. Our team met weekly during the 2016-17 academic year to work through these stages. The prelude to that year of analysis, though, was a pilot project that Rebecca ran several years earlier. In 2012, Rebecca had developed a rough coding schema based on 16 transcripts of writing center conferences; from this work the initial concept of “transfer talk”—meaning, at that point, “a process of articulating knowledge, attitudes, and identities previously associated with an earlier context and connecting them to a new context”—had emerged. This notion of transfer talk was simply a taxonomy of different ways in which people spoke out loud their previous knowledge; it was not a claim of intentional or effective repurposing of writing-related knowledge.

While the positive response she received to the presentation of that pilot data persuaded Rebecca that analyzing writing center conferences to develop the idea of “transfer talk” was a viable project (Nowacek Genre), she was also aware that her initial analyses did not go far enough. In order to build a robust understanding of how transfer of learning might be scaffolded through conversation, more transcripts would need to be analyzed more thoroughly and by multiple researchers. Therefore, when this new research project began, Rebecca did not share her earlier taxonomy with the full team lest it over-determine what might emerge from transcribing and open coding. In short, although we began this project with the term “transfer talk”—a term which, with its emphasis on “talk,” reflected our commitment to looking at writing center conversations about writing in progress—we proceeded with no commitment to what exactly transfer talk might look like or how (and even whether) it might illuminate the related-but-distinct phenomenon of transfer of learning.

Transcription: Casting a wide net. Once we began our group analyses in Fall 2016, each of the five initial undergraduate W.R.I.T.E. Fellows (a sixth Fellow joined our team during the second semester of the project) was responsible for being the “primary” transcriber of six randomly assigned conferences. Ideally, we would have produced full transcripts of each conference, but because conferences were at least 30 and sometimes 60 minutes, this was an unrealistic goal. Instead, we undertook what we called a process of “selective transcription.”

To begin, each researcher identified and transcribed what they considered to be every potential instance of “transfer talk,” guided by the PI’s provisional definition: “A process of articulating knowledge, attitudes, and identities previously associated with an earlier context and connecting it to a new context.” Because this definition was quite vague, the transcription process took over a month as we discussed in weekly meetings what might and might not constitute transfer talk. We transcribed what we came to call “exchanges”—excerpts from the conference that included dialogue directly before and after to provide context for a moment of possible transfer talk. Some exchanges contained multiple possible instances of transfer talk.

After these first drafts of transcripts were developed, each video was subsequently reviewed by two additional researchers. Each of the five undergraduate researchers (in addition to being the “primary transcriber” of six videos) was a “secondary” transcriber of six more videos. “Secondary transcribers” would watch the video and read along with the existing transcript, adding other possible instances of transfer talk and making notes to question whether some earlier transcriptions did indeed constitute transfer talk. And every transcript was eventually reviewed by a third researcher: after the coding schema described below was finalized and before the transcripts were systematically coded, the PI watched all 30 videos and (where appropriate) made additions to all 30 transcripts.

This three-person transcription process provided multiple opportunities for each member of the research team to learn from and with the other researchers. Although a “selective transcription” process may seem tautological—i.e., we set out to transcribe instances of transfer talk so everything we transcribed became, necessarily, an instance of transfer talk—in fact it was part of our effort to keep our minds open to our large set of data. Weekly research meetings provided a forum for challenging initial ideas of transfer talk and developing much broader understandings of the concept. That emergent, more capacious shared understanding allowed the second and third transcribers to add exchanges as the transcription process continued, casting as wide a net as possible. In short, although we did not have full transcripts, we drew on the perspectives of multiple people over multiple iterations to include in the transcripts all the moments that we thought might possibly have to do with transfer.

Coding schema development: Narrowing the scope. Although the transcription process was iterative and demanding, developing a coding schema for “transfer talk” from those transcripts was the central—and most difficult—part of this project. Once we had developed transcripts that included as many possible examples as we could find, we worked through those transcripts to develop a more precise (and in some cases more exclusionary) coding schema. The process of developing the coding schema moved through several stages.

-

First-pass coding with six transcripts. After all 30 conferences had been transcribed, we chose six transcripts to begin our coding. (Here and throughout the entire data analysis process, we sought to adopt methods of grounded theory [Strauss; Saldaña].) At this stage, two months into the process, we began to notice patterns and ask questions that were prompted more by the data than by our preexisting expectations. For instance, we began to focus on who initiated the transfer talk and whether it took the form of a question or a statement. As our coding schema grew to highlight the interactions between the writer and tutor, we also chose to limit our focus in this project to transfer talk from writers{2}.

-

Second pass coding with four additional transcripts. At this stage, four more transcripts were closely analyzed in full team meetings, bringing us to a total of 10 transcripts used to refine the codes and strengthen our ability to use them consistently. During this stage, our three major categories—Individual Memories, Question Asking, and Co-Construction—stayed constant but some subcategories were collapsed while other new ones appeared.

-

Firming up the coding schema. At the start of the Spring 2017 semester, we added a new W.R.I.T.E. Fellow to the team. Her addition afforded the opportunity to see how clear our categories were to a party not intimately involved in their development. Her contributions—as well as our efforts to jointly code another six transcripts—allowed us to consolidate some categories and develop others. Eventually, we developed the document included in Table 1, complete with codes, descriptions, and examples.

Importantly, much of this stage of our work involved identifying examples of conversations that were not transfer talk. (For instance, when was saying “I don’t know” a declaration of not knowing versus a modesty or politeness strategy? Or, was every account of a personal experience transfer talk?) Our effort to transcribe all possible examples of transfer talk was counter-balanced as multiple exchanges were deemed (through the development of the coding schema) not to be examples of transfer talk. Thus the coding development phase was, in many ways, far more selective than the “selective transcription” phase.

Transcript analysis: Implementing the results systematically. Using the coding schema presented in Table 1, each one of the 30 transcripts was coded by three researchers who talked until they came to consensus on how to code each exchange; in order to provide continuity, one researcher (the PI) participated in coding every exchange in all 30 transcripts. The prevalence of the various types of transfer talk was then tabulated, as shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Types of Transfer Talk

|

Type of Transfer Talk |

Description |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Question Asking |

||

|

Request for writing advice |

A question to elicit a tutor’s advice about writing (often drawing on the tutor’s genre or writing process knowledge). |

“So should I put without protein up here because he kind of wants us to define everything?” “For poem[s], that’s where I get confused ...cause like how do you address the thesis statement for poems?” |

|

Request for evaluation of writing |

A question to elicit the tutor’s evaluation of the quality of the writing. |

”What do you think, overall? Do you think I would have failed if I had turned it in now?“ |

|

Establishing tutor expertise |

A question to gauge how much specific content knowledge or experience a tutor might have. |

“This is from The Magician’s Nephew. Have you read that book?” |

|

Request for content expertise |

A question to elicit tutor knowledge about the actual content being discussed in the writing. |

“Is ethos the one that deals with emotion?” “Can you just name a few [rhetorical appeals]?” |

|

Individual memory: Not knowing, course context, statements about writing, statements about self as writer |

||

|

Individual memory: Declarations of not knowing |

||

|

An answer when a writer is asked for information and doesn’t seem to have it. (Only applies when the writer clearly can’t answer a tutor’s question; does not include statements that may be hedges or politeness mitigations.) |

T: What do you think sounds best if we put these three into the thesis? W: I don’t know. T: Okay, well how do you think we should fit it in. W [[long silence]] I don’t know. |

|

|

Individual Memory: Statements about course context | ||

|

Course Context: Sharing information about writing assignment or instruction |

A statement where the writer explains some aspect of the writing assignment or instructor preferences. |

“This is the open form prose essay. It’s just like you have to take something that happened in your life and relate it to a social or political issue.” |

|

Course Context: Sharing evaluation of writing |

A statement sharing clearly evaluative assessments or advice from the instructor. |

“He read my thesis and said it wasn't descriptive enough so I tried changing the words.” |

|

Course Context: Sharing course goals or language |

A statement invoking language specific to the course. |

“This is called a PICO.” |

|

Individual memory: Statements about writing |

||

|

Statements about writing: I remember/I was taught statements |

A statement explaining principles or strategies the writer learned about writing from a particular person or prior experience. |

“I learned the 5-paragraph essay in 8th grade, and that’s been drilled into my head. So now I’m kind of not too sure how to write another one, a different style.” |

|

General statements about writing |

A statement or evaluation that invokes vocabulary for or understanding of writing, not tied by the writer to any particular experience. |

“Well this topic sentence I feel like is pretty weak. It sounds a lot like something I’ve already written.” |

|

Individual memory: Statements about the self as (good or bad) writer | ||

|

Personal history: Story about writing |

An account of a specific experience with writing. (Unlike an “I was taught” statement, there is no explicit statement of what was learned.) |

“But then again I went into office hours for Jane Austen and he was like this is great blah blah blah and he said the same thing, sit on it for a day, look it over and then turn it back in, and then you’re fine. And I did that, got it back, got an AB and I was like why didn’t you tell me, like I know you’re not going to grade it ahead of time but you could have been like do this, do this, do this.” |

|

Personal history: Generalization about self as writer |

A statement about the writer’s usual patterns or how the writer feels about their writing skills in general. |

“I’m just not a good writer, I personally think.” |

|

Personal history: Prior knowledge or experience informs content |

A statement in which the author works to determine whether their previous personal, academic, or workplace experience would be relevant for the writing project at hand. |

“Yeah I just I wasn’t sure with these last couple paragraphs if it was all like relevant because this is actually something that we just talked about in psychology so it made me think of like ... [writer is cut off] |

|

Co-Construction |

||

|

|

Moments where tutor and writer interact over several conversational turns, each drawing on their own experiences in order to collaboratively develop a strategy for or an understanding of a phenomenon. |

W: Before I was reading this over and it says, it literally says, get page number. And I sent it to him like that! I forgot! T: Oh yeah, I’ve definitely, or you put it in all caps like CITE. W: Yeah. GET IT. T: Like visual notes to yourself, like will you please explain this you idiot. And then you send it to your professor and you’re like ah that was me talking to myself. That’s part of my revision process. |

Table 2. Frequency of Transfer Talk in Writers

|

Type of Transfer Talk |

How many times did each type of transfer talk appear (n = 357) |

How many writers engaged in this type of transfer talk (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|

|

Question Asking | ||

|

Request for writing advice |

81 (22.6%) |

24 |

|

Request for evaluation of writing |

22 (6.1%) |

15 |

|

Establishing tutor expertise |

9 (2.5%) |

6 |

|

Request for content expertise |

17 (4.7%) |

9 |

|

Individual Memories |

||

|

IM: Declarations of not knowing |

30 (8.4%) |

9 |

|

IM: Statements about course context |

||

|

44 (12.3%) |

18 |

|

11 (3%) |

7 |

|

10 (2.8%) |

9 |

|

IM: Statements about writing |

||

|

8 (2.2%) |

6 |

|

73 (20.4%) |

22 |

|

IM: Statements about self as writer |

||

|

9 (2.5%) |

6 |

|

20 (5.6%) |

12 |

|

15 (4.2%) |

14 |

|

Co-Construction |

8 (2.2%) |

5 |

Discussion: Building a model of “transfer talk”

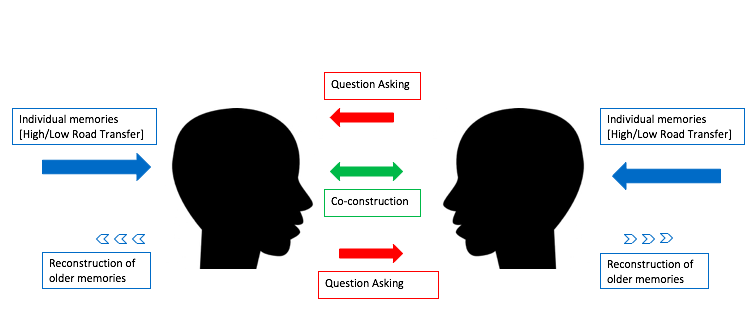

As indicated in the descriptions of our data analysis process, our understanding of transfer talk changed over time. Through the process of open coding, we came to define transfer talk as the talk through which individuals make visible their prior learning (in this case, about writing) or try to access the prior learning of someone else. Transfer talk, as it emerged through our coding, appeared in three forms: Question Asking, Co-construction, and Individual Memories. These three types are diagrammed in relation to each other in Figure 1 and described in more detail below.

Figure 1. Transfer talk

As we have already suggested, once we identified these three types of transfer talk, we found that they and their subcategories led us to reconsider, even challenge, our theories of transfer of learning. Thus, in the discussion that follows, we put forward two propositions. In the first proposition—grounded in the red and green portions of the model that focus on Question Asking and Co-construction—we argue that transfer of learning is potentially a far more social, even collaborative, cognition than is ordinarily recognized in the writing studies literature. In the second proposition—grounded in the blue portions of the model, which focus on Individual Memories—we raise questions about the centrality of conceptualized knowledge and abstraction for transfer of learning, arguing that transfer of learning may be facilitated by more automatized associations as well.

Proposition #1: Transfer of learning may have an important social, even collaborative, component

Through our analyses, we came to define transfer talk as the talk through which individuals make visible their prior learning (in this case, about writing) or try to access the prior learning of someone else. Our first proposition focuses on the second half of that definition: recognizing efforts to “access the prior learning of someone else” shifts the focus from a single individual to exchanges between two individuals. One of the initial challenges of this project was the messiness of two people surfacing their prior knowledge simultaneously and in conversation with each other. At first, we thought the problem was methodological: sometimes we found it difficult to separate the moment in which writers surfaced their prior knowledge from moments in which that happened for tutors. For several months we persisted in the belief that we simply needed a more precise coding schema to break up and break down those interactions. Eventually, though, as we came to embrace Question Asking and Co-construction as key parts of our coding schema, what had been a major obstacle unexpectedly metamorphosized into a central insight: namely, the interactive nature of those transfer talk exchanges was perhaps illuminating rather than disguising the nature of how transfer of learning might occur.

Again, transfer talk is not synonymous with transfer of learning. It is instead a construct that allows us to focus not on the final decisions that writers make about texts (did the writer transfer some knowledge or a certain ability from an earlier context to a later one?) but rather on the ways in which writers bring their prior learning into play as they discuss their writing in progress. In the pages that follow we illustrate these types of transfer talk, then explore their possible implications for how we conceptualize transfer of learning.

Question Asking. The interactive nature of transfer talk is perhaps most readily visible in the category of Question Asking. Question Asking, in our data set, goes both ways: tutors ask questions of writers to attempt to get writers to tap into their prior knowledge, and writers do the same. Writers tended to ask questions that focused on evaluating the text in progress: requests for advice, requests for evaluation, requests for content expertise, and questions meant to determine whether the tutor even had content expertise.

In fact, as Table 2 indicates, Requests for Advice and Requests for Evaluation were the transfer talk writers were most likely to engage in. Twenty-four of the 30 writers made 81 requests for writing advice—over 22% of the 357 instances of transfer talk we coded. Requests for evaluation were less common (n=22, or 6.1%), but were widely distributed: fully half of our 30 writers requested that tutors evaluate their text. We were unsurprised by this finding: writers visiting a writing center are often very concerned about their grades and eager to secure specific advice to gauge if they are on the right track. Less often, writers sought to determine whether tutors had content expertise (asking if they had taken a certain course or read a certain book) and, if so, attempted to access that expertise.

Our focus on Question Asking highlights how the concept of transfer talk differs from what has traditionally been identified as transfer of learning; we categorize Question Asking as transfer talk because it represents an effort “to access the prior learning of someone else” through talk. Transfer talk’s unit of analysis is not, ultimately, an individual making choices about a draft, but two or more individuals in conversation about that draft.

Co-construction. Although moments of Co-construction were relatively rare (only eight instances restricted to five writers), their occasional presence was another factor that (together with Question Asking) helped us recognize that interaction was not a messy problem to overcome but an insight into how transfer of learning about writing might occur. By Co-construction we mean exchanges where tutor and writer interact over several conversational turns, each drawing on their own experiences in order to collaboratively develop a strategy for or an understanding of a phenomenon. We find helpful here Winzenried et al.’s distinction between co-telling (in which individuals “form an agreed upon viewpoint” but their pre-existing ideas go unchallenged) and co-constructing (in which individuals “complicate and nuance one another’s ideas in order to jointly construct their [new] understanding”). As in Winzenried’s examples, our moments of co-construction are premised on interactions with a conversational partner and potentially offer an opportunity to revisit and “reconstruct” (Nowacek, Agents) prior experiences in light of the current context of learning. However, our model of co-constructing might also include Winzenried et al.’s co-telling.

Table 1 contains a very brief illustration of how tutors and writers can pool their knowledge to build a shared understanding of a phenomenon—in this case, whether a particular revision strategy is embarrassing or not.

W: Before I was reading this over and it says, it literally says, get page number. And I sent it to him like that! I forgot!

T: Oh yeah, I’ve definitely, or you put it in all caps like CITE.

W: Yeah. GET IT.

T: Like visual notes to yourself, like will you please explain this you idiot. And then you send it to your professor and you’re like ah that was me talking to myself. That’s part of my revision process.

This modest example of co-constructing transfer talk gives a sense of how two individuals might share their experiences in order to build a richer conceptualization of the revision process.

Affiliative talk such as this has long been recognized as important in writing center work (Jefferson; Thonus; DeCheck; Godbee; Mackiewicz and Thompson). But we would argue that in addition to a sort of “troubles telling” that leads to rapport, this moment is also transfer talk. In this exchange, the prior experiences of both writer and tutor come to the fore to be processed and possibly even reconstructed. In this case, the writer’s initial account of an embarrassing mistake (sending a drafty draft to her instructor) is potentially reconstructed as an example of how this writer owns a revision process that avoids getting bogged down in details. If we understand transfer to be not simply the application of prior knowledge, but an opportunity to repurpose and reconstruct prior knowledge and experiences, then this exchange provides an example of how collaborative transfer talk might support such repurposing and reconstructing.

A longer example, taken from a conference between a graduate tutor and a writer working on a high-stakes presentation for her graduate-level nursing course, similarly demonstrates how some kinds of affiliative talk can also be understood as a transfer talk.

T: Yeah, I think the best way to do it is to do practice run-throughs. Of course, you work all weekend but if you can just fit one in where you just do it in front of the mirror. Or, I can’t believe I’m telling you this, but what I do is I have a camera at home and I set up the camera and I actually do it in front of the camera.

W: Well, I do do it in front of the mirror, with a timer

T: Yes! That’s exactly it.

W: to watch my timeframe

T: Exactly. Yes.

W: So I do do that, because I cannot just walk up there and talk about it.

T: No. Yeah, yeah, I...

W: Two of the students who got up there last week both have a teaching background.

T: Oh yeah?

W: And they were really good, and I’m just like, wow, I’m not that classy. So they did a really nice job so I will just have to work on it.

T: Mm-hmm. And the only reason I bring that up is you have to know your stylistic preference. If you like to read, if that makes you feel comfortable, by all means, I tell people, then you have your sentences there, to fall back on. If you need them, just have a bullet point to separate them so you don’t lose your spot.

W: And you can mix in between both of them, uhm, because if I get nervous, I talk faster, I get easily distracted, so I just kinda want to do a mixed combination to make sure I’m hitting the sentences I need. Because they expect us to not be reading from our PowerPoint, so they expect us not to be reading from our notes. We need to talk through it, so I might just have one bullet point. One of the students read fairly closely, they seemed to have pretty detailed sentences with their work that that they had, so.

T: Yeah, and, a lot of people know this, but it’s just interesting because some of the people I’ve talked to here. When you make this you’re thinking about this, you’re kinda thinking about how you’re going to be using this in the future, but if you can try to think about, as you’re trying to. As you’re constructing your, don’t know what you would call them.

W: My outline, my presentation of my interventions.

T: Yeah, your outline; if you could try to think about like what is it going to look like with faces, or like when I look down, what am I going to see when I do that. That’s helped me, and that’s helped some other people that I’ve worked with, so. You know, because I never think about that either when I do outlines.

Throughout this exchange we see both writer and tutor marshaling a diverse set of prior experiences to develop a strategy for the writer’s 30-minute presentation. Although the writer has (several moments before this exchange) bemoaned the fact that she has to work two 12-hour shifts before her presentation the following week, the tutor encourages her to practice on her feet, out loud, with strategically developed notes. To do so, he draws on his own experiences (“I can’t believe I’m telling you this, but what I do is I have a camera at home and I set up the camera and I actually do it in front of the camera”) as well as his experiences coaching other writers (“That’s helped me, and that’s helped some other people that I’ve worked with”). The writer in turn engages in affiliative talk that draws on her own prior experiences practicing presentations (“Well, I do do it in front of the mirror, with a timer”) and her sense of exactly what type of outline she needs to manage her nerves (“If I get nervous, I talk faster, I get easily distracted, so I just kinda want to do a mixed combination to make sure I’m hitting the sentences I need”).

Some readers may question the accuracy of these statements made by the writer and tutor, which are, in essence, self-reports; those self-reports might be swayed by either individual’s desire to decrease social distance by engaging in affiliative, rapport-building talk. We share that concern and agree: if we wished to make a claim about the writer’s actual transfer of learning, more investigation into the writer’s prior experiences and actual practices during her presentation would be necessary. However, we are not making a claim about the writer’s actual practices; the concept of transfer talk means that our focus is limited to the ways in which the writer brings into this conversation her prior experiences and knowledge or tries to gain access to the tutor’s prior knowledge. Our goal is not to make a claim about whether the writer actually repurposed knowledge or skills from her prior experiences to her 30-minute presentation but to explore how transfer talk might illuminate how transfer of learning potentially unfolds while a piece of writing is in progress. We believe that such moments of surfacing prior knowledge may prove important and have certainly been under-examined in existing research.

To the extent that we have a more ambitious goal, it is this: to consider how these moments of co-constructing and question asking might raise questions about how we as a field have theorized transfer of learning. Although we do not believe our data can support a claim about how and whether transfer of learning occurred for this writer, we do believe these two categories of transfer talk highlighted in our coding schema raise questions about the nature of transfer of learning.

Generally, scholars studying transfer have treated transfer as an act of individual cognition, taking single individuals as their unit of analysis in interviews and textual analyses. Even when the work of many writers is aggregated, the focus remains on the writings from and the interviews conducted with individual writers rather than writers in interaction with others. But when we analyzed talk related to writers’ prior writing experiences as it occurred during writing center conversations, we began to notice how transfer of learning might potentially be cued and even co-constructed.

Such a focus, while rare, is not unprecedented. For instance, our findings intersect with the notions of expansive framing developed in psychology by Engle and colleagues (Engle; Engle et al.). They argue that how a teacher frames—that is, makes a “metacommunicative act of characterizing what is happening in a given context” (Engle et al. 217)—an instance of initial learning can strongly influence subsequent transfer of that learning. Although Engle and colleagues focus on the relative merits of expansive versus bounded framing, we wish to draw attention to how Engle’s research highlights interactions between individuals.

A far more radical understanding of collaboration is offered by Wegner’s notion of a transactive memory system (or TMS). Originally developed to explain the “cognitive interdependence” of individuals in intimate relationships, Wegner and colleagues draw from their analyses of talk between romantic partners to argue that both members of the partnership don’t each remember everything. Each remembers some higher-order and some lower-order information, but importantly they both remember the location of information—that is, who knows which higher- and lower-order information. Although the writing center conversations analyzed here are hardly instances of talk between long-term partners, the theory of transactive memory systems has been extended to examining collaborations in workplaces (Lewis and Herndon); such work suggests the value of further examining the potentially collaborative dimensions of transfer of learning.

In a similar vein, a handful of writing studies scholars have noted how important conversation can be for transfer of learning. In their study of pedagogical memories, Jarratt and colleagues note that “students’ reflection on writing memories during the interview enabled them to create pedagogical memories linking disparate college writing experiences” (62, emphasis added). Their observation that even the experience of conversing during interviews may have helped participants build pedagogical memories suggests how conversation might facilitate transfer of learning. Furthermore, Jarratt’s point about the power of collaborative reflection during the interview also aligns with Yancey’s recent observation that reflection itself may have a more collaborative dimension than generally recognized.

Similarly, Winzenried and colleagues offer an excellent account of how conversation “enable[s] students to collaboratively build rhetorical knowledge.” Their analyses of groups of undergraduate students discussing their work in shared courses identify (as indicated earlier) two approaches: co-telling and co-constructing. Importantly, though, Winzenried and colleagues make the more general point that students’ abilities to “abstract process or subject matter knowledge beyond the limits of a single assignment” frequently “emerge[d] through co-constructed conversation” (emphasis added). They conclude that the ability to engage in co-constructing conversations is itself useful transferrable knowledge, and that “there is value in viewing transfer as a collaborative process.”

In sum, we see in the transfer talk activities of Co-construction and Question Asking that the marshaling (and even reconstructing) of writers’ memories might be a far more collaborative endeavor than is generally recognized. When combined with the work of others, these types of transfer talk suggest the need for more research into the possibly collaborative nature of transfer of learning.

Proposition #2: Although meta-awareness and conceptualized knowledge about writing have long been recognized as valuable for transfer of learning, less conceptualized, more automatized knowledge may play an important role as well.

Writing studies scholarship on transfer of learning has emphasized the value of meta-awareness and conceptualized knowledge, arguing for the importance of conscious transformations of writing-related knowledge. The very first of the Elon Seminar’s five “essential principles” of writing transfer is that “Successful writing transfer requires transforming or repurposing prior knowledge (even if only slightly) for a new context” (Moore 4). Such transformations, Moore is careful to note, can take two forms: “both routinized (low road) and transformative (high road)” (4). This high-road / low-road distinction, taken from the work of Perkins and Salomon, has enjoyed significant uptake throughout the field of writing studies. Low-road transfer “reflects the automatic triggering of well-practiced routines in circumstances where there is considerable perceptual similarity to the original learning context” (Perkins and Salomon 25); for instance, when a person sits down to drive a truck after having only ever driven cars, “the steering wheel begs one to steer it, the windshield invites one to look through it, and so on” (25). High-road transfer “depends on deliberate mindful abstraction of skill or knowledge from one context for application in another” (25) and can be either forward looking or backward reaching.

Many scholars have recognized the particular value of high-road transfer’s effortful, mindful control—suggesting that it can facilitate transfer across multiple contexts. Within the field of psychology, Hatano and Inagaki “have argued that not all types of expertise are equal.” Routine experts, in their estimation, “are outstanding in terms of speed, accuracy, and automaticity of performance.” The skills of routine experts are “highly effective for solving everyday problems in a stable environment,” but routine experts “lack flexibility and adaptability to new problems” (31). Adaptive expertise, on the other hand, “can be flexibly altered to respond to a variety of novel situations” and might be built up from routine expertise by learning from the variation of experience.

Multiple writing studies scholars have also argued for the value of such adaptive expertise. Beaufort (College Writing), for instance, argues that “learners need guidance to structure specific problems and learnings into more abstract principles that can be applied to new situations” (151) and that “teaching the practice of mindfulness or meta-cognition” can “increas[e] the chances of transfer of learning” (152). Yancey et al.—pointing to Bransford et al.’s observation that full competence requires not just factual knowledge but the ability to contextualize those ideas “in the context of a conceptual framework” (Bransford qtd. in Yancey et al 137)—explain that a central focus of their Teaching for Transfer curriculum is to help each student develop their own theory of writing. Such an individually developed theory of writing can help students “organiz[e] what they have learned about writing through remixing prior knowledge, new theory, and new practice” in ways that “will support their moving forward to new contexts” (137). Crystal VanKooten, grounded in case studies of six FYW students, argues that meta-awareness of composition can take four component forms (process, techniques, rhetoric, and intercomparativity); such meta-awareness, she argues, “may be important for the transfer of writing knowledge from one context to the next.”

Our second proposition does not aim to dispute the value of high-road transfer. The value of such conceptualized knowledge has been carefully and convincingly documented in Yancey et al.’s Writing Across Contexts and elsewhere (Adler-Kassner et al.; Taczak and Robertson). We aim instead to direct attention to the ways in which talk about writing in progress actually unfolds, and the ways it suggests that valuable transfer of learning might be happening even in the absence of a framework of conceptualized knowledge. Toward that end, we first explain the different types of Individual Memories that came into play during conversations about writing in progress, then explore the implications those categories of transfer talk might have for our understandings of transfer of learning.

Transfer talk about Individual Memories was what we most expected to find when we began this project. Nevertheless, as we developed the coding schema, how we coded for Individual Memory as a type of transfer talk narrowed considerably. For instance, during conferences, writers frequently summarized readings they had done for class; although writers may indeed have drawn (in such moments) on things they’d learned previous to that conversation, such instances did not constitute transfer talk about writing because the writers were not focused on their prior learning about writing. Ultimately, we identified four types of Individual Memories—course context, statements about writing, statements about self-as-writer, and not-knowing—each with its own sub-categories.

Statements about the course context were prevalent (n=65, or 18.2% of coded instances), but statements about writing were the most frequent type of individual memory surfaced through transfer talk (n=81, or 22.6% of the coded instances). Transfer talk about the writer’s sense of self-as-writer, in comparison, was relatively low (n=44, or 12.3% of coded instances). Not knowing was concentrated in nine of our 30 writers; although not terribly widespread in the overall corpus of transcripts, (n=30, or 8.4% of coded transfer talk), those writers who did offer declarations of not-knowing tended to do so repeatedly in their conferences.

Course context. Very often (n=65, or 18.2% of the coded instances of transfer talk) the connections writers made were to their immediate course context. Combined with the requests for advice and evaluation in our Question Asking section, they illustrate how transfer talk in these writing center conferences was most often focused on the immediate task of the assignment: n=168 or 47% of our recorded instances of transfer talk. These connections to the course tended to be of three types.

First, writers would simply share information about writing from the course; this often took the form of describing what had been discussed in class (“Um, we didn’t talk so much about the paper, but we talked about, like, reading with and against the grain ... and he mentioned a little bit about incorporating that into it, subtly”) or the writer’s sense of what was expected in the paper (“So there were two required articles which is this one, that I mentioned, and at least two background articles” or “Because it’s a poem our instructor requires that we find some meter or rhythm or something”). Sometimes these descriptions seemed to us to be informed by genre knowledge, other times not. Eighteen of 30 writers engaged in this type of transfer talk, making it one of the most widespread types of transfer talk, occurring in 12.3% of our coded instances (n=44).

Second, writers would share evaluations or advice they had received from their instructors. In our conferences, seven writers shared evaluations from their instructors 11 times. These instances of transfer talk consistently took the form of negative evaluations: for instance, “He read my thesis and said it wasn't descriptive enough” and “My teacher says that’s not good, that’s not telling me why or how.” Indeed, we found only one example, in our entire data set, of a writer sharing a positive evaluation from an instructor—and even that example demonstrated deep anxiety about the instructor’s feedback. In this example (which was prefaced by another exchange coded as “story about writing”) the writer begins by telling a story of how, in a previous course, she had been told that her draft was in good shape only to receive a disappointing grade; the writer then shares the current instructor’s commentary and asks the tutor to help her interpret it.

W See, pretty good, exclamation point.

T Okay but now I’m going to overanalyze. He did say pretty good, not just good.

W Yeah, he didn’t call it good. But it could mean preeeeetty good, it’s preeetty good. It’s average, pretty good. [[laughs]] I don’t know.

Even in this example of looking at what may be praise, the writer has only shared it because she is concerned that the praise isn’t really praise. Consistently, then, instructor evaluations surface in transfer talk as an ominous, critical presence.

Finally, we sometimes saw writers sharing course language. For instance, when describing his efforts to analyze the poetry of Langston Hughes, one writer explained to his tutor that Hughes “used a lot of things like rhythm, the tone, the denotation, and connotation.” On other occasions, writers invoked course language and concepts as a means of explaining things that initially puzzled tutors: “This is called a PICO.” Most often in our sample (which was heavy on papers from our university’s first-year writing course) we found writers referring to ethos, pathos, logos, reading against the grain, and other terms that were highlighted in the course curriculum.{3}

Of particular interest within our emerging concept of transfer talk, though, were those occasions when writers would reach back further than the immediate course context to articulate their sense of what was working well or not in their writing. We found that these comments about prior knowledge and experiences branched into two sorts of statements. More often (n=81, or 22.6% of coded instances), writers offered statements about writing, in which they invoked their knowledge about writing, either through writing-related vocabulary or evaluations of their text. Throughout these statements, writers surface their knowledge about writing by invoking criteria and standards that seem to exist independent of their own experiences and identities. Less often (n=44, or 12.3% of coded instances), writers offered statements about themselves as writers: stories about previous writing experiences, self-generalizations about what kinds of writers they are, and reflections on how they had incorporated previous experiences in the actual content of their papers. Throughout these statements, writers surfaced and even constructed their own narrative of what type of writer they are and how their personal experiences with and learning about writing informed this particular moment.

The distinction between statements about writingand statements about self-as-writer is imperfect but nevertheless highlights an important dimension of how writers articulate their prior knowledge about writing. Specifically, our team’s pre-existing interest in how students might operate as “agents of integration,” how they might work to develop integrated and empowering visions of themselves as learners (Nowacek, Agents), led us to be particularly interested in those moments in which they spoke of themselves as writers. Those moments were disappointingly rare, with implications we will discuss below.

Statements about writing. Approximately 22% of the instances of transfer talk (n=81) were moments in which writers went beyond sharing their concerns about or knowledge of their immediate course context in order to surface prior learning about writing. The most obvious of these statements about writing were tagged with phrases that indicated how the writer had acquired this knowledge about writing: “I remember/I was taught statements.” One clear example can be seen in a writer’s explanation that “I learned the 5-paragraph essay in 8th grade, and that’s like, been drilled into my head. So now I’m kind of not too sure, like, how to write another one, a different style.” A less direct example of the “I remember” statement can be found in a writer’s admission that “I don’t know why I do that. I just kind of thought that’s what you had to do. Maybe my high school did that.” However, only six of our 30 writers made such statements for a total of eight instances (2.2%). The relative scarcity of “I remember” statements highlights how much more common the less overt invocations of prior learning about writing are.

These other statements about writing took several forms. Frequently, they took the form of evaluations of the draft under discussion. Writers sometimes invoked specific criteria to evaluate their draft, with statements like “I don’t think I did a good job because I feel like I was sort of repetitive” or “I had five paragraphs but they were so long I had to split them up.” In other cases, writers expressed a gut feeling that something was wrong with a draft without being able to name what concerned them: “This paragraph is just sad” or “I was writing my thesis and thought ‘That was really bad.’” Writers also surfaced their prior learning about writing through their use of vocabulary and concepts that simply assume a shared knowledge about writing. Sometimes that prior learning took the form of genre knowledge: “we can do this magazine style because this isn’t academically oriented” or “So this one [draft of a personal statement] reads more like a dissertation proposal. There’s less while-I-was-here-I-did-this-as-a-result-of-that.” In other instances, writers simply invoked writing-related vocabulary in statements like “I think this is a run-on.” The prevalence of these various statements about writing demonstrates that writers are often drawing on their prior learning about writing, despite common laments to the contrary.

Statements about the self as (a good or bad) writer. Stories about oneself as a writer were a type of Individual Memory transfer talk that writers were extremely unlikely to engage in. Only six writers shared stories about their prior writing experiences. By far, the most elaborated account was the story (mentioned earlier) that a writer shared about the misleading feedback she had received in a previous course. The other eight “stories” were far more compact, offering a one- or two-sentence glimpse into experiences such as how a writer had been taught to compose in China or how the writer had composed a personal statement when applying to college.

Twelve of the 30 writers, however, made generalizations about themselves as writers (n=20 or 5.6%). Sometimes those generalizations focused on specific struggles in writing:

-

“A lot of the times I write things that make sense in my head but to someone else they don’t make sense.”

-

“Because word count, I’m always low.”

-

“I’m not the greatest writer. I feel like I either overuse commas or don’t use them enough.”

In many other instances, though, writers simply offered a negative self-evaluation, without any specifics:

-

“I really don’t like to write. I’m just not a good writer, I personally think.”

-

“I’m bad at English.”

-

“I’m also not a very good writer.”

We are struck by the fact that not one writer in any of our 30 conferences offered a generalization about things they were good at: e.g., “I’m pretty good at transitions” or “I know how to analyze evidence in a paragraph.” No doubt this is due partly to the rhetorical situation of the writing center conference, a situation in which writers arrive seeking out constructive criticism. However, the complete absence of positive self-generalizations also suggests the possibility that writers may not have articulated for themselves—much less to anyone else—their skills and strengths as writers.

Finally, writers also made a third, very different kind of statement about themselves as writers when they considered how their prior knowledge or experience might inform the content of the current paper. This type of transfer talk, though less overtly about writing, was relatively widespread among writers, including 14 of the 30 writers (n=15, or 4.2%). For instance, when deciding what to include in her personal statement for applying to graduate school, one writer talked through her concerns with her tutor:

I’m a part of AZD and Autism Speaks and ... I also took a class [...where we] went out and did service-learning and had a focus student that we observed, helped through the semester, then wrote a big write up on. So I talked about how those experiences helped develop my passion for those with disabilities, especially in the autism community ... I’d like to highlight that if I could.

Although the question of what personal experiences to include may seem like an unavoidable topic of conversation in conferences on personal statements, we found similar types of transfer talk arising in conferences on a wide range of projects.

For instance, a student in a first-year writing class, asked to compose a memo persuading a fictional supervisor to change workplace policies, contemplates including his own real-life workplace experiences:

Can I say something? Maybe I should probably mention this in the paper. The store I worked at, we had a 15-minute break and that was it. That’s why I’m asking [for] an extra 5-, 10-minute increase.

This type of transfer talk is an occasion for writers to assess the degree to which their prior experiences and interests would be appropriate to include in the paper. Previous research suggests that students often intentionally choose to omit their personal interests and experiences from papers (Nowacek, Agents; Wardle and Mercer Clement), so this type of transfer talk—while not directly about an emerging writerly identity—is very much an occasion for writers to make choices about how much they can move towards being agents of integration.

Not knowing. Declarations of not knowing may seem counterintuitive as a type of transfer talk. After all, saying “I don’t know” seems to deny a connection. But because we’re interested not in transfer of learning but in transfer talk—the talk through which individuals make visible their prior learning about writing or try to access the prior learning of someone else—such declarations take on importance. Robertson et al. have identified a related phenomenon they name “absent prior knowledge.” They document the ways in which high school students arrive to college “missing the conceptions, models, and practices of writing ... that could be helpful in a postsecondary environment.” While “absent prior knowledge” documents (as the term clearly indicates) an actual gap in the writer’s existing knowledge, the transfer talk category of “not knowing” indicates a type of participation in the conversation: in this case, when a tutor asks a question or gives a prompt to a writer and the writer responds that they do not possess any relevant knowledge.

Methodologically, tracking declarations of not knowing was complicated by the fact that individuals will say “I don’t know” for many reasons—not solely because they lack knowledge. Our transcripts were littered with moments when writers (and occasionally tutors) demurred, claiming to not know things. Everyday experience suggests a range of explanations: saying “I don’t know” can function as a politeness strategy, a modesty strategy, an expression of frustration, or an opening gambit—even when people do know the thing they’re claiming not to know. At first, as researchers, we were torn: how could we know whether someone actually did or did not know what they claimed not to know? Over time, though, we adjusted our coding schema to focus only on those moments when a participant (in this project, the writer) was directly asked for information and they replied that they did not have it.

This category came to our attention through our analysis of a transcript from a video that had initially been brought to a staff meeting (a semester before we began this research) as an example of a resistant writer. What we found, though, as we examined the transcript through the lens of transfer talk, was a writer whose apparent resistance might have been more aptly understood as a profound sense of disconnection from her own educational experiences. The writer was a first-year student enrolled in an introductory history course that asked her to write a paper from primary sources on Roanoke and Jamestown. At the start of the conference, her declarations of not knowing marked a gap between her instructor’s advice and her own understanding:

T: So you’ve read the articles. What do you think the three most important things are you should look at?

W: See my problem is with the articles, I can’t pick them out. He [the instructor] told me the articles should work but after reading I’m not seeing it.

As the conference continued, the writer’s declarations of not knowing shifted, not only directing attention to her uncertainty about the paper but also her evaluation of her skills as a writer.

T: What do you think sounds best if we put these three into the thesis?

W: I don’t know.

T: Okay, well how do you think we should fit it in?

W: [long silence] I don’t know. I’m really bad at this stuff.

Although we understand why the tutor perceived the writer’s responses as a type of stubborn resistance, we see in them now an expression that the writer feels that she simply does not have the knowledge necessary to rise to the task, that there’s nothing in her prior experiences—in the course or as a writer with a history of learning beyond the course—that can help her in this moment.

T: Does that sound good? Does that sound like something you can start to think how the articles fit?

W: [silence] I think after, after we pull some out ... [Writer sighs] My problem is I don’t know anything about Roanoke or Jamestown—

T No, that’s fine. You don’t have to know—

W: —I can’t pull things out of here. I just [long pause] am not good with history. Like I don’t know what ...

T: Yeah, I mean think of this ... are you in RC 1001? Are you in English 1001?

W: [After a pause, she gives a tiny shrug] Uhm, yeah, I think so?

In the very moment that the writer is admitting defeat in this course (“I don’t know anything about Roanoke or Jamestown”), the tutor first gamely tries to reassure her (“No, that’s fine. You don’t have to know”) then decides to try to help her make connections to her first-year writing course, which (because it was required of nearly every first-year student on our campus) this writer is almost certainly enrolled in (“Are you in RC 1001?”). But by this stage of the conference, this writer seems so unmoored, she no longer seems to have a clear sense even of which classes she is taking.

In such declarations of not-knowing, we identify a type of transfer talk that speaks not to the ability to draw on prior experiences but rather gives expression to the writer’s sense that they have nothing—in their course context or their legacy of schooling—that can help them in this moment. This type of transfer talk, frankly, saddened us—but we identify it as an important type of transfer talk nonetheless. If we aim to build a more robust theory of how people repurpose their knowledge, we would do well to attend to these moments when writers insist, even when prompted to make connections, that they have no relevant knowledge.

Taking these examples of Individual Memories as a whole, we are struck by how often and in how many different ways individuals’ prior knowledge of writing is in play when they talk about writing in progress. Sometimes writers can clearly identify where they acquired that knowledge and can use it to evaluate their current draft in intentional ways. In many other cases, though, that knowledge—whether it takes the form of casually used writing-related vocabulary, gut feelings about the problems in a draft, or throw-away pronouncements about what they do and don’t do well as a writer—is far less thoroughly developed. That does not mean, however, that such prior knowledge may not be important for transfer of learning. These individual memories of writing-related vocabulary and experiences may indeed be at play—perhaps in ways that are less successful for a writer navigating new rhetorical contexts than conceptualized knowledge might be, but certainly in ways less often acknowledged and studied within our scholarship.

Motivated by the frequency and variety of these individual memories in transfer talk, we aim in these final few pages to weave together research from writing studies and from other fields to argue that our second proposition—that less conceptualized, more automatized knowledge may play an important role in transfer of learning—merits further research within the field of writing studies.

Although, as we argued earlier, writing studies scholarship has often highlighted the value of high-road transfer, Perkins and Salomon’s model is in quiet conversation with a long tradition of psychology research focused on attention, memory, and perception. More specifically, Perkins and Salomon’s work emerges from an ongoing exploration of dual-processing theories. Dual-processing theories hold that in order to process the constant influx of various stimuli, every individual possesses “two different modes of processing” characterized by “processes that are unconscious, rapid, automatic, and high capacity, and those that are conscious, slow, and deliberative” (Evans 256; see also Shiffrin and Schneider; Kahneman, Attention and Effort, A Perspective, Thinking, Fast and Slow). Daniel Kahneman—a cognitive psychologist who later became famous for his Nobel Prize winning work on economic judgment and decision-making—calls those two processing systems “System 1” and “System 2” and explains that

The operations of System 1 are typically fast, automatic, effortless, associative, implicit (not available to introspection), and often emotionally charged; they are also governed by habit and are therefore difficult to control or modify. The operations of System 2 are slower, serial, effortful, more likely to be consciously monitored and deliberately controlled; they are also relatively flexible and potentially rule governed. (Kahneman, A Perspective 698).

Systems 1 and 2 are very much like Perkins and Salomon’s high and low road transfer—but here, as in much of the dual-processing research, there is a persistent focus on the complementary nature of these two systems.

In his best-selling Thinking Fast and Slow, Kahneman offers a book-length defense of the importance of—and the dangers of writing off—System 1 (that is, thinking fast). Drawing on cognitivist research on attention, Kahneman argues that the routinized automaticity of System 1 is where skilled expertise, built up over long periods of time, resides. He acknowledges (drawing on his decades of research with Tversky into the often misleading heuristics of decision making) that System 1 is also where less informed intuitions reside. But he also adds that this is not a fault of System 1, merely the reality of how System 1 co-exists with System 2.

Indeed, Kahneman suggests, if there is blame to be allocated, it should fall at the feet of the mindful abstractions of System 2, which are often too slow to kick in. It is easy to fault System 1 for leading people to the kind of intuitive mistakes that Kahneman so famously spotlighted throughout his work with Tversky on biases and heuristics. After all, Kahneman notes, “When we think of ourselves, we identify with System 2, the conscious, reasoning self that has beliefs, makes choices, and decides what to think about and what to do.” But, Kahneman adds, System 1 should not be so easily dismissed: “Although System 2 believes itself to be where the action is, the automatic System 1 is the hero of the book” (21). In short, Kahneman and others in the tradition of research on attention offer an important counterbalance to the dismissal of automaticity implicit in Perkins and Salomon’s valorization of the mindful abstraction of high-road transfer.

And in fact, multiple writing studies scholars have argued for the importance of examining the role of more routine, automatized experiences of transfer more carefully. Donahue notes that “although much has been made of ... meta-awareness as one of the key components of successful transfer, some research is beginning to question its role”; preliminary results from her own study suggest that “mature practices might indeed develop without an accompanying meta-awareness” (150). Nowacek argues that although “conscious awareness of the rhetorical dimensions of genre” are helpful, they may not always be necessary for transfer (142). Schieber argues that although her two case studies evidenced “excellent use of rhetorical flexibility,” that transfer was “unintentional” and “invisible” not only to the instructor but to the students themselves (480). Ringer has argued for a post-human theory of transfer that would, he argues, not foreclose the value of metacognition but would invite us to consider it more critically. And although Wardle’s claim that “meta-awareness about writing, language, and rhetorical strategies in FYC may be the most important ability our courses can cultivate ” (Understanding ‘Transfer’ 82) is often cited in work spotlighting the value of meta-awareness, she has publicly noted that her claim was fundamentally about what the FYC course is best suited to do—not a claim that meta-awareness is required for transfer of learning (Researching Transfer).

In sum, analyzing transfer talk about Individual Memories demonstrates that the writers in this data set were frequently drawing on prior experiences with writing that stretched beyond the immediate context of their current course. Those prior experiences sometimes surfaced as specifically located memories and well-developed evaluation criteria. But they also frequently surfaced in the casual use of vocabulary and fleeting evaluations of a draft or of themselves as writers. These unelaborated references are not proof of transfer of learning, but they do suggest that in order to better understand transfer of learning we need to explore carefully the more implicit, less thoroughly conceptualized understandings of writing that writers draw on as they navigate new contexts for writing.

Implications

We began this research with the belief that because conversations about writing in progress have not often been used as a means to study transfer of learning, focusing on such a data set might cast new light on transfer of learning. Throughout this article, we have offered two propositions we believe merit future research, focused on the potentially collaborative dimensions of transfer of learning and the role more routinized knowledge might play. In addition to exploring those propositions, we hope that other researchers will take up and refine the transfer talk coding schema itself; approaching new transcripts from different writers and tutors—or teachers, or classmates—may affirm the centrality of some codes, question the usefulness of others, and introduce new types of transfer talk that didn’t emerge from this necessarily limited data set.

Methodologically, we hope that other scholars interested in transfer of learning will also adopt a focus on exchanges between multiple individuals. In addition, we believe that future research could helpfully supplement analyses of conversations with additional data; for instance, analyses of transfer talk in writing center conferences might be triangulated with interviews with the tutors and writers in the videos being analyzed and the texts actually composed. Such analyses could explore more fully the relationship between transfer talk and the actual repurposing of learning that individuals engage in when composing their texts.

Turning our attention to more immediate pedagogical implications, we learn from our research that writers engage in transfer talk more often than some research would lead us to expect, but not always in the ways we had anticipated. Those statements we had originally imagined as the quintessential (or at least the most easily recognizable) instances of transfer talk—the “I remember/I was taught” statements—occurred relatively rarely. Recognizing their relative scarcity as well as the frequency of talk about the immediate context of the assignment leads us to propose that conversational partners can and should engage writers in transfer talk beyond the assignment. Tutors and teachers might actively seek to facilitate more transfer talk by asking questions that invite stories and memories about writing; they might listen for fleeting allusions to prior knowledge and create opportunities for these recollections. For tutors, this might be especially relevant at the beginning of a conference, when tutors frequently ask questions that gather information about the immediate rhetorical context (e.g., “What kind of assignment are you working on?” “When is this paper due?”) but less frequently ask more open questions that promote other types of transfer talk (e.g., “What do you know about writing history papers?” or “What experience do you have with writing literature reviews?”). In this way, conversational partners might encourage writers to bring their prior knowledge and experiences into play, enabling engagement beyond the assignment and helping writers to cultivate and affirm a positive writerly identity.

On a similar note, the transfer talk framework has also helped us—in our work as tutors and teachers—engage writers with greater empathy and a wider range of conferencing strategies. Coming to see declarations of not knowing as a type of transfer talk helped us understand those writers—some of whom we had formerly dismissed as resistant—as struggling to make any use of their prior learning. Perhaps facilitating transfer talk through asking questions and inviting stories can make writers more aware that they do indeed have some amount of previous knowledge and writing experience to draw on. Such conversations are a space where transfer talk can be cultivated to encourage writers not only to work productively on the assignment at hand, but also to become more confident in articulating and repurposing what they have already learned. In the meantime, we hope that a wide range of conversational partners for writers—in the writing center, in classrooms, and elsewhere—will find in this research an impetus to hear more clearly the fleeting instances of transfer talk and to expand their understanding of the potential of such interchanges to facilitate transfer of learning.

Notes

-

Sponsored by a grant from the Helen Way Klingler College of Arts and Sciences’ Mellon fund, the W.R.I.T.E. (Writing and Research Integrative Tutor Experience) Fellows Program sponsors collaborative undergraduate research in Marquette University’s writing center. More specifically, each semester, five tutors are selected as Fellows; each receives a stipend to work collaboratively on a research project developed by the writing center director. W.R.I.T.E. Fellows meet weekly to discuss their research and put in three additional hours each week. (Return to text.)

-

Although we elected to focus on writers, we believe that analysis of transfer talk from tutors is a future project that will benefit from the theory of transfer talk developed by first focusing on writers. (Return to text.)

-