Composition Forum 54, Summer 2024

http://compositionforum.com/issue/54/

“Why Am I Here?”: Exploring Graduate Students’ Academic Writing Anxieties and the Potential for Contemplative and Mindfulness-Based Teaching Practices

Abstract: Mental health challenges, notably anxiety, disproportionately affect graduate students, with research indicating a 41% prevalence rate compared to the general population (Evans et al.). Academic writing anxiety (AWA) stands out among these concerns, correlating with lower grades, self-esteem, and self-efficacy (Martinez et al.; Daly and Wilson; Goodman and Cirka). Traditionally, AWA has been viewed through a cognitive lens, neglecting its complexity. To address this, we conducted a comprehensive survey gathering both quantitative and qualitative data on graduate students’ AWA experiences. Our analysis of student narratives unveils how academic cultures alienate marginalized students, fostering impostor syndrome and AWA. We advocate for integrating mindfulness-based and contemplative pedagogies within feminist and anti-racist frameworks (Mathieu and Muir; Inoue; Graphenreed and Poe) to catalyze transformative change amid this pressing historical moment.

Understanding Academic Writing Anxiety (AWA)

We find ourselves in a remarkable historical moment in higher education. We are grappling with an extended pandemic’s effects on physical, emotional, and mental well-being, and we are also witnessing the impact of growing awareness about the long-term, significant effects of academic policies and practices based in systemic, institutionalized racism, sexism, and ableism. In many ways, academia is being challenged to confront long-held assumptions about who is welcomed and supported in higher education and who is not, how and why the practices that create those realities originated, and what needs to be done to create lasting, sustainable change.

Questions about how to address inequities and ineffective practices are prevalent in all areas of higher education, but undergraduate education often attracts the most research attention, specifically questions of undergraduate retention and persistence. Yet mental health challenges, especially anxiety, also affect graduate students at alarming rates. Recent studies have found that 41% of graduate students could be suffering from anxiety, a number that is six times higher than the general population (Evans et al.).

Thankfully, an increasing number of researchers are studying well-being in graduate education, where hardship has long been perceived as a rite of passage instead of a barrier to access and learning. Looking at the context of medical education, Mari Ricker and Victoria Maizes et al. published an initial longitudinal study of the effects of medical school on residents and found that several factors, such as emotional exhaustion and burnout, were high for students when they completed their MD and that those effects had increased over their three years of medical school (716). In a follow-up study, Ricker and Brooks et al. found that a course designed for incoming medical students that included contemplative activities such as gratitude journaling, meditation, and journaling about finding meaning had a positive impact on several well-being outcomes (123).

Ricker et al.’s studies of medical students align with the findings of other work in educational psychology and socio-emotional learning that conclude that well-designed, contemplative writing activities have the potential to improve well-being (Neff; Pennebaker). Yet scholars in writing studies have also found that writing in school contexts is often a source of anxiety for students. While academic-related anxieties come in many forms (Cassady), a prominent one is academic writing anxiety (AWA). AWA has a causal relationship with many negative cognitive, academic, physical, and social outcomes which include lower grades (Martinez et al.), lower self-esteem (Daly and Wilson), and lower self-efficacy (Goodman and Cirka); perspiration and palpitations (Cheng); increased procrastination (Onwuegbuzie and Collins); low writing performance (Sanders-Reio et al.), and avoidance of majors and jobs that are writing-intensive (Daly and Shamo). As Miller-Cochran and Cochran point out, many writing scholars have highlighted the potentially harmful impacts of our teaching and assessment practices in higher education. Much of that harm can be traced to long-held assumptions about writing instruction and assessment that are grounded in racist and ableist practices.

Research has thus far studied AWA primarily from a cognitive paradigm that perceives the anxieties students experience as “individual differences” which can be measured purely by quantitative means (Daly and Miller; Cheng; Huerta et al.). To begin to understand AWA as a complex, multidimensional construct that is simultaneously a cognitive, socio-cultural, and ecological phenomenon, we conducted a multi-phased mixed-methods study with just over one hundred graduate students from a range of disciplinary backgrounds and institutions of higher education in the United States. To do this, we designed a multi-layered survey (see Appendix A) to collect quantitative as well as qualitative data about graduate students’ experiences with AWA.

Choices in Research Design

In this article, we dive into the lived experiences of the graduate student participants, looking in-depth at their qualitative responses on the survey. The narratives that students shared with us provide insight into the complex ways that AWA shows up in graduate students’ experiences and the multidimensional nature of AWA as a construct. In these responses, students described the factors that they identified as causing their AWA, and they also described the strategies they had used to address AWA (including, at times, the success of those strategies). We conclude by exploring the potential for how contemplative and mindfulness-based pedagogies can proactively address many of the causes of AWA that graduate students report. When these strategies are implemented in courses and even at programmatic and disciplinary levels (Yagelski and Connor), they can spark transformative change that is especially needed in this historical moment.

To analyze our participants’ qualitative narratives, we followed Saldaña’s “descriptive coding” method, individually reading through and assigning codes to our participants’ responses. These codes were each a short phrase that “assign[ed] basic labels to data to provide an inventory of their topics” (97). Then we met to discuss our codes and started to arrange them in relation to each other to find larger categories, themes, and patterns in our data. Instead of seeking a positivist inter-rater reliability in this process, we turned to Smagorinsky’s (401) collaborative coding method, where reliability of codes is reached through discussion of the data to reach resolution. This is a generative and flexible process that foregrounds the interpretive role that the positionality of the researchers plays in their analysis. Given our differing areas of expertise and our positionalities (Anuj: graduate student, international, brown, male, experiencer of AWA, privy to underrepresented graduate students’ experiences; Susan: tenured professor, white, American, diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder and generalized anxiety, experienced teacher and researcher), we agreed that a collaborative coding model would make our interpretation more meaningful and reliable.

Factors that Graduate Students Identify as Causing AWA

We received responses from 102 graduate students who identified a range of causes of their AWA. The following larger codes emerged from the qualitative responses from the participants:

|

Code |

Percentage |

|---|---|

Academic Culture Academic Discourse Problems with Supervisors Publishing Culture Lack of Funding & Jobs |

56% 56% 20% 17% 14% |

Impostor Syndrome |

38% |

Positionality |

17% |

Table 1. Causes of AWA.

1. Academic Culture

The most predominant cause of academic writing anxiety for many of our participants is the nature of academic culture itself, which we coded as having the following four main categories based on participant responses: academic discourse, problems with professors, publishing culture, and lack of funding and jobs.

1.a) Academic Discourse

Fifty-six percent of our participants identified the nature of academic discourse itself as a cause of AWA. Within this category, we found several important sub-categories that clarify what aspects of academic writing are most anxiety-inducing, with the most common being evaluation (47%). One of our participants describes how this anxiety prevents them from sharing their work more broadly when they write, “I’m not sure my writing makes sense to other people and I fear that my work seems baseless or trivial. This anxiety usually appears after I’m done writing a section or a paper and it makes me put off submitting the paper to any journal or send it to peers for feedback.”

For some participants this evaluative aspect also leads to concerns about the highly competitive nature of academia. When considering publishing their work, one participant worries about “Not knowing if it will be sabotaged by other academics.” As we will see later in the code for positionality, a lot of these concerns about evaluation are deeply tied to issues of race, disability, gender, nationality, and class.

Apart from evaluation, for some graduate students, genre features of academic writing like academic jargon and grammar (12%) or specific genre types like IRB applications, dissertations and exams (7%) make them anxious. One participant told us that the vastness of academic jargon and conceptual vocabulary is a major source of AWA: “Sometimes lack of knowledge of concepts makes me anxious - not because I actually don’t know enough, but because academic literature often feels so endless and copious.”

1.b) Problems with Professors

Another aspect of academic culture that 20% of participants identified as causing AWA are situations that result in challenging communication with professors or direct supervisors, often involving feedback. One participant described that “I have a very picky professor who has very set answers in his mind of what he wants and I am always afraid he will grade harshly.” For several participants, it is the absence of any feedback at all from supervisors that makes them anxious.

Additionally, experiences of abuse, bullying, or microaggressions from professors or supervisors is another cause of anxiety, including AWA. One participant writes that “A professor doesn’t like me and makes it clear in class by ignoring me or dismissing everything I say. So I am anxious about submitting anything [in writing] to him.” Another participant experienced plagiarism at the hands of a professor, which has made their experiences with academic writing very difficult: “I had a bad experience with a previous advisor who was abusive. We worked on a writing project–my friend and I did most of the work, the professor did very little, but she is 1st author.”

1.c) Publishing Culture

The “whole publish or perish mentality” in academia, as one participant puts it, is another significant contributor to AWA for over 17% of graduate students. One describes that “Pressure to publish makes me the most anxious because it feels directly tied to my career success.” For many of these participants, problems of gatekeeping in publishing add to their worries. One participant laments the lack of clear standards in reviewers’ decisions: “reviewers are all different. In one journal, I am criticized for X, then then a second journal might appraise X.” Many reviewers also have monolingual biases. According to one participant, “when they see a non-native user of English, they automatically tend to reject - they may claim otherwise.”

1.d) Lack of Funding and Jobs

Lack of funding and jobs in academia further plagues another 14% of our participants. A participant describes that “anxiety with jobs impacts me the most because I am unsure if I am doing enough to get me a decent job after all of this.” Another agrees by saying, “Everything feels pointless when I think about the job market.” For many graduate students, the “lack of funding” within PhD programs adds to this financial stress. One participant describes how this situation results in not being able to pursue the research they are interested in: “Because of the pandemic, I cannot see many people face-to-face, and it makes finding participants very hard, not to mention that people do not like to contribute their own time to other people’s research if they cannot get monetary compensation.”

2. Impostor Syndrome

A second common cause for AWA for our participants is impostor syndrome, or a feeling of “persistent self-doubt and fear of being exposed as a fraud or impostor” (Bravata et al.,1252). A staggering 38% of our participants feel this is a significant cause of their AWA. One participant describes that “feelings of being an impostor” are a consistent part of their academic experience, while another says that AWA makes them feel like “I’m not good enough or not a ‘real scholar’ so to speak.” Another participant sums up different facets of impostor syndrome that we saw reflected in many of our participants’ narratives:

My feeling of being an imposter impacts me the most. I sometimes feel as though I am hugely under-qualified relative to the rest of my program and I imagine that my (poor) writing will “expose” me as a fraud or lead my advisors to think they were mistaken in accepting me to the program. Rationally, I don’t believe this; I know my work is adequate and, at times, quite good, and that comparing myself to other members of my cohort is neither helpful nor emotionally healthy. However, this “rational” understanding does very little to change my emotions or physical reactions to writing tasks.

These negative self-evaluations are often instigated by comparisons and coupled with pressures for performativity. All of this leads to low confidence, but what is striking is that it often happens in spite of rational awareness of one’s talent and capabilities.

3. Positionality

Seventeen percent of our participants also noted that their positionality, or their identity/ies borne out of their socio-political context(s), was a significant contributor to their experience of AWA. Participants discussed how their race, disability, gender, class, health, disability status, nationality, and/or family issues were tied to experiences of linguistic discrimination and a sense that due to their marginalized positionality, participants were perceived to be less intelligent than their dominant peers. The complex nature of positionality helped us understand more deeply the contexts that can influence the first two codes: academic discourse and imposter syndrome.

3.a) Race

Graphenreed and Poe explain that “the institutions of academe, the university, and other vestiges of colonial infrastructure cause many of us feelings of powerlessness, voicelessness, and alienation” (53) because “our departments and universities drown out the voices and subjectivities of marginalized people and students in favor of white speakers, which results in alienation and heartache at being made to feel invisible or silenced” (55). These patterns in academia connect to the alienation described by participants in the first two codes (academic culture and imposter syndrome) and help us understand that graduate students who are historically marginalized, especially those who are multiply marginalized, might experience the first two causes of AWA more frequently and/or more severely due to their positionality.

Participants reported several aspects of positionality having such an impact. One participant describes the way that race impacts their AWA very lucidly:

If I was in an environment where I believed my English variant, non-dominant way of thinking, and (my) way of writing based on my cognitive thoughts (which aren’t white) were embraced and encouraged, I would excel and have less anxiety. […] (for) minoritized black and brown bodies, before we can pick up a pen or sit before a computer to compose a line, they have already made the decision that it won’t be good.

For another, their racial identity requires them to prove their worth much more than their peers: “I have the impression that I have to work thrice as hard as my caucasian colleagues, and yet, I am not good enough. I don’t know if my science is good enough to be published or if I have anything I can teach the scientific community.”

3.b) Health and Disability

For four percent of our participants, health and disability are additional contributors to their academic writing anxiety. One participant says that “health [is] the most common issue for myself. My PhD program does not offer full health coverage, and there have been several issues I had to pay out of pocket.” Another has specific health conditions that make it difficult for them to write: “I am also a person with lupus who gets brain fog and cannot process too well sometimes. It is quite frustrating when I sit down to write or to try to reach for a word in my brain but it will not come due to illness.” They also serve as a caregiver for family members with disabilities which prevents them from giving enough time to their writing, thereby creating anxiety around it: “I have a husband and son on the autism spectrum. It is hard for me to focus on me and my writing needs when they [need] something.”

3.c) Sex and Gender

Apart from race and health/disability status, sex and gender also were aspects of identity that participants mentioned as impacting their AWA. As one participant describes: “I am also anxious about whether male professors will perceive me as capable. I have occasionally had anxiety attacks in front of professors and I worry sometimes that to male professors, this may mean I’m ‘emotional’ and therefore not capable.” Another participant feels that “As a queer person, I suspect that much of my negative self-image, lack of confidence, and at times unhealthy desire to exceed other peoples’ expectations stem from internalized discrimination and a sense of perpetual outsiderhood in academia. I believe a lot of my causes for writing anxiety are directly linked to being queer in a heternormative/ heteropatriarchal society and academia.”

3.d) Nationality

In terms of nationality, many international students experience immense AWA due to the linguistic discrimination they face. One participant says that “I do feel like an outsider in the US system, thereby feeling a higher pressure of proving myself. But when I sit down to do it, it feels like a lot so I keep wanting to give up.” This induces a sense of unnaturalness for another participant: “I feel less confident with the ‘accent’ of my writing, it doesn’t seem natural.” A different participant also agrees that “when they [reviewers] see a non-native user of English, they automatically tend to reject - they may claim otherwise.” Apart from discrimination, other experiences which induce a sense of alienation in international students also contributes to their AWA. Another participant, for example, says that “Yearning for my family… makes me feel like what I am doing is not worthy enough. This home sickness makes me feel like I am consuming important time to write nothing.”

3.e) Socioeconomic Status

A final aspect of positionality mentioned by participants is socioeconomic status. For one participant, their class identity is the predominant reason behind their AWA:

I feel as a first-gen college student from a working class background, it was impressed upon me that I should do well in school and listen to the teachers, but not really to be intellectually curious and to see my teachers as mentors. I think there’s a disconnect for some of us working class kids where we see teachers as authority figures that we need to make happy, not as facilitators for our own personal and academic growth. And I think that had a negative impact on how I view my relationship with professors down the line. It took a really long time for me to realize how much I needed mentorship and I’m still trying to figure out how to really solidify those mentoring relationships.

Understanding and addressing these important, and often complex and interconnected, aspects of positionality as directly related to AWA is essential to begin working toward meaningful solutions. As Graphenreed and Poe explain in their 2023 article, we “cannot truly support well-being without a fully antiracist and justice-oriented approach to writing, research, teaching, and action in the world” (54).

Strategies that Graduate Students Report Using to Address AWA

In addition to describing the causes of their AWA, our participants also reported different strategies they have tried using to address AWA. As we coded the responses, we identified which strategies were more inward-focused and which were outward-focused, involving other people, environments, or materials. In the table below, we have listed the reported strategies as “inner” and “outer” to reflect that distinction. We have not distinguished between strategies that might contribute to or detract from well-being:

Code |

Percentage |

|---|---|

Inner Strategies to Address AWA Procrastination Emotional Well-Being Practices Exercise Writing Process Strategies |

45% 15% 15% 13% |

External Strategies to Address AWA Building Social Relationships Curating Physical Environments Increased Financial Support Substance Use Writing Support |

37% 34% 10% 6% 5% |

Table 2. Strategies for Addressing AWA.

1. Inner Strategies

Participants identified several strategies that are more inward-facing and that they use to address AWA. Several of these strategies potentially impact the participants’ inner psychological or emotional worlds without explicit engagement or emphasis on entities beyond themselves or their control.

1.a) Procrastination

A staggering 45% of our participants report using procrastination as a response to their AWA. Interestingly, for some of our participants, procrastination enables greater cognitive control. One participant describes using procrastination to circumvent or strongarm their writing anxiety. They write that “if a paper is due, it’s due. I need to get it done. I simply don’t have time for all of my anxiety if a paper is due the next day, so procrastination helps me.”

Most of our participants, however, described their procrastination as an unhealthy coping mechanism. One participant wrote that “I usually procrastinate because I’m so overwhelmed and anxious to get started. I feel as though I’ve already failed before I’ve even begun or like there’s no point in starting because I won’t complete it anyway.” For many participants, procrastination is a way to avoid other negative physical and cognitive symptoms of AWA to include fatigue, insomnia, restlessness, indifference, and even suicidal ideation. For these participants, procrastination is a way to delay experiencing such symptoms by avoiding academic writing tasks.

While this strategy might help with some symptoms in the short term, for many participants, procrastination ultimately results in increasing AWA. As one participant writes, “procrastination causes a vicious cycle of increased stress and anxiety because the writing is not getting done. You play a video game to take your mind off the stress you feel, but you stress out more because you could have spent that time on the writing and now have less time overall.”

1.b) Emotional Well-Being Practices

Sixteen percent of our participants engage in various practices that contribute to emotional well-being, such as journaling, meditation, affirmations, developing emotional intelligence, self-care, or everyday activities that help participants experience relaxation, like cooking or listening to music. Our participants either learned about these practices from others or by reading about well-being and positive psychology. One participant describes that “Meditat[ing] helps me to compare myself less with others and keep focused on doing the best I can and keep hopeful about the future.” Another participant uses a mixture of techniques: “My journaling is usually done using strategies that my therapist has suggested. I write dialogically sometimes: one side describing my fear, and the other side asking questions about it to dig deeper and then refute it. I write affirmations to myself or I write about my values and how my work fits in with my values.” Several participants also practice one or more forms of self-care activities like nature walks, sleep, reading books for pleasure, music, watching movies, cooking, cleaning, arts and crafts, and social media surfing. Finally, about five percent of participants describe finding solace in prayer and spiritual practices.

1.c) Exercise

Fifteen percent of participants use exercise as a tool to tackle their AWA. One participant explains that “ I often exercise so that I can move my body. Writing is such a mental activity that I need to move my body to balance things out.” For another, exercise works especially well for the physical manifestations of AWA: “I also handle the physical [effects] really well through exercise.” Another participant describes how exercising leads to a greater sense of general confidence, which indirectly contributes to reducing AWA: “I exercise for health reasons, but I think it impacts my emotional state as well, it makes me feel like I can tackle things better.”

1.d) Writing Process Strategies

About 13% participants use writing process strategies that are often taught in college composition classrooms. These strategies include outlining, list-making, tracking progress, drafting, and breaking down writing tasks into manageable chunks. One participant says that “I try to complete one section at a time” while another says that “I tend to take short breaks when I’m in the middle of writing a paper that makes me anxious.” One participant describes a strategy of “time-tracking to see where my timing is going and then block off specific times in my calendar for writing to do the writing whether I’m ‘feeling like it’ or not. This helps me get over my anxiety and just do it.” Yet another participant says that “One way that I tend to try and manage anxiety is by free writing and doing outlines of a paper before starting a full draft.” For another, “writing to-do lists” is also an effective strategy.

2. Outer Strategies

Many participants described using outward-facing strategies that engage them socially or rely on entities beyond themselves.

2.a) Building Social Relationships

Thirty-seven percent of our participants engage in some form of social relationship-building to tackle their AWA. Some report relying on family and friends, while others (22%) describe healthy relationships with academic community members as vital to reducing their AWA. Some develop peer relationships with other graduate students, and others describe reliance on relationships with faculty advisors. One participant wrote that “I’ve been extremely fortunate to have had incredible supportive advisors throughout the entirety of my academic career; their feedback on my work always helps alleviate anxiety I feel.”

2.b) Curating Physical Environments

Thirty-four percent of our participants note that selecting or curating a writing environment that is conducive to writing decreases their AWA. Some described ideal spaces that would help decrease AWA, including one participant who wrote that “I [wish I] had a space outside of my small apartment to go and write. Space is important; it demarcates a place that one can use that is separate and allows focus.” Another participant describes changing locations to write: “When I’m able, I rotate where I write. I find that a new place can help with anxiety.” Others describe the importance of sensory input and light.

2.c) Increased Financial Support

Ten percent of participants feel that increased financial support would greatly reduce their AWA. This would help reduce the amount of time and energy that students spend on worrying about managing basic things like groceries and bills, which would automatically give them more mental and physical resources to allocate to their writing tasks. One participant explains this well by saying that:

Part of my anxiety comes from struggling to find time for writing. As a graduate student I manage several different responsibilities, including work outside of my program in order to make ends meet. It’s impossible to get around the fact that if my assistantship paid a living wage, I would have more time for writing and less anxiety overall.

2.4) Substance Use

About six percent of participants report using some form of substance to deal with their AWA. Participants listed substances such as alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and energy drinks.

2.5) Writing Support

Surprisingly, only five percent of participants report using writing resources available to them on campus to tackle their AWA. One participant mentions that “ I’ve dealt with writing anxiety by going to the campus writing center.” Other participants describe using social media groups where graduate students offer each other advice and solace about their academic writing anxieties.

Intentionally Addressing AWA: Contemplative Pedagogies and Social Justice Advocacy

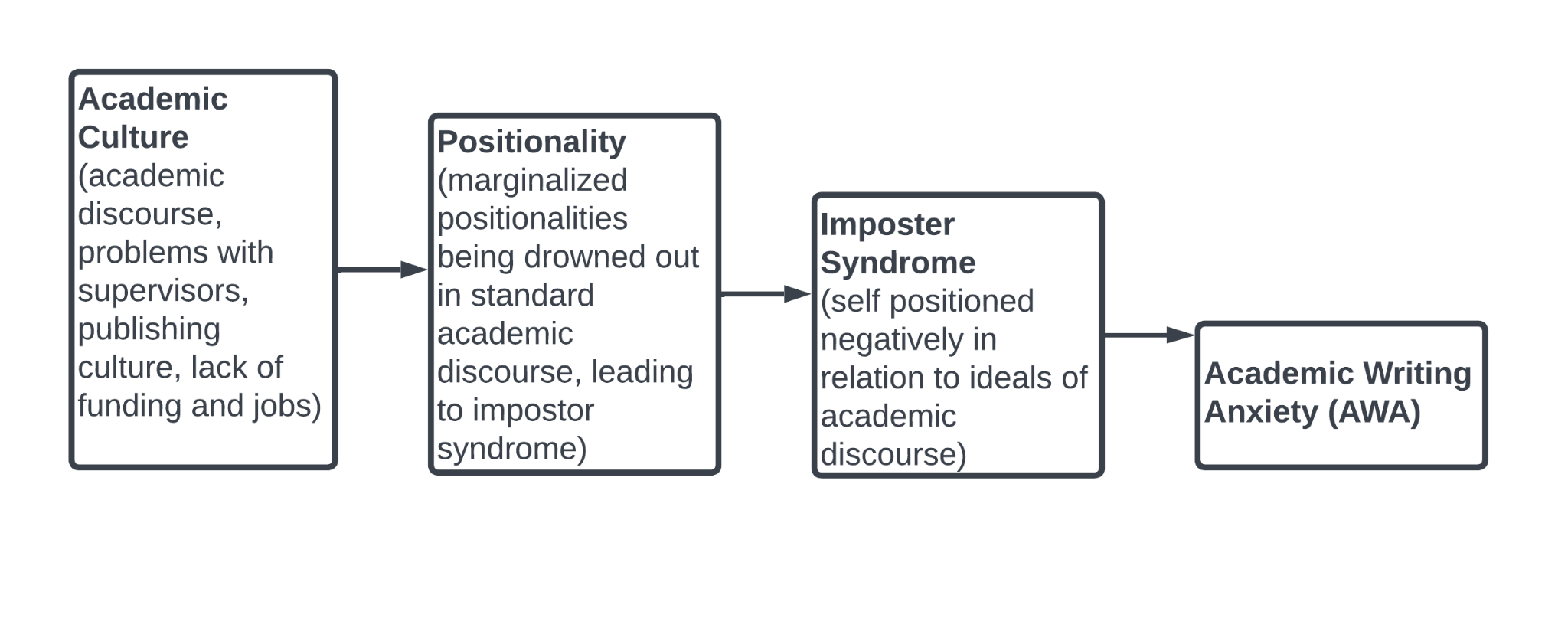

Listening to and engaging with the responses of graduate students in our study revealed that many of the strategies that graduate students use to address AWA are ones that they have adopted to address symptoms of AWA rather than causes. This approach is completely understandable since the causes that many of our participants listed are not causes over which they exert control: academic culture and positionality, both of which can result in a decreased sense of belonging that leads to imposter syndrome.

To relieve the impact of AWA more comprehensively, we need to proactively address systemic issues that create AWA in the first place through individual, social, and institutional mechanisms at various levels. Two frameworks, when used in combination, provide a way forward: contemplative pedagogies and institutional reforms that lead to greater social justice in academic spaces. These reforms include anti-racist and feminist advocacy and coalitional work. Contemplative pedagogies can help address the physical and cognitive effects of AWA which, as our participants told us, are so severe for many of them that they prefer avoiding academic writing altogether through procrastination which increases these symptoms in the long term. But moving toward greater social justice is necessary to address the ecological factors that cause those symptoms of AWA in the first place.

These two frameworks are sometimes seen to be at odds. For example, Belli warns us that “our field’s enthusiastic uptake of contemplative practices and approaches may bring some of positive psychology’s ideological inflections to writing studies through the back door.” Belli encourages writing studies scholars and teachers not to ignore external, structural problems that transfer the responsibility for stressful experiences and emotions on the individual. Our data and experiences, along with emerging literature in the field such as Weisser et al. and Miller-Cochran and Cochran (2022), however, show that there are productive ways that contemplative practices and social justice work can and should be combined to develop critically-informed mindfulness pedagogies. Specifically, we offer two sets of recommendations for what graduate instructors and program administrators might do at the course as well as the program and discipline levels to develop effective ways of responding to the prominence of AWA among graduate students.

1. At the Course Level

First, we suggest that instructors and students conduct collaborative, reflective writing sessions in their classes where they map out the causes of AWA in their specific experiences. The heuristic in Figure 1, developed through analysis of our participants’ responses, can guide this mapping. Such a heuristic is only intended to be a starting point for initiating reflection, but the initial mapping can then be developed through contemplative writing prompts that encourage graduate students to explore their unique experiences of AWA.

Figure 1. Causes of AWA: A Heuristic.

As a starting point, students could write about the specific four categories and sub-codes within the heuristic to reflect not just on their internal, emotional experiences of AWA, but also institutional and material factors that contribute to it. As they write, they should then be encouraged to expand and redesign this heuristic in ways that best suit their experiences. It would be helpful for instructors to do such contemplative writing about their own AWA experiences to help reiterate the idea that AWA is a common issue. To assist in developing this exercise, instructors could draw from existing emotional literacy assignment designs like those developed by Carlo and Campbell.

Second, we encourage instructors to engage mindfulness practices such as reflection and journaling to have students track and understand their responses to various writing tasks and situations. Where do they find that they experience the most focus in their writing? At what time of day? Do they feel less or more anxious when writing in the presence of others or when sharing writing in progress for feedback? Developing awareness of one’s own responses to various stimuli and writing environments will help students identify supportive practices, people, and spaces for their writing.

2. At the Program and Disciplinary Levels

Once graduate students have engaged in exercises such as the mapping activity described above, graduate program administrators should work with instructors and students to collate the results to understand the range of causes behind students’ AWA in their programs. With that understanding in mind, they should develop initiatives targeted towards tackling those causes systematically. Are there specific points in the program where students experience increased anxiety? Do students from specific demographic groups experience more anxiety than others? Based on our own experiences as well as results from our study, we recommend developing training and discussion sessions that integrate mindfulness approaches with anti-racist and feminist pedagogies to develop coalitional efforts that lead to institutional reform.

Graduate programs can also provide training for both faculty and students that acquaints them with the rich body of literature in writing studies that discusses pedagogic exercises that help participants regulate their nervous systems, cultivate well-being, reframe their relationships with difficult emotions, and develop awareness of systemic issues that engender suffering. Some of this training should focus on exercises that tackle physical aspects of AWA. Muir and Mathieu, for example, provide a range of very useful grounding and breathing exercises that teachers can use in their classrooms to achieve this. Their ‘three breaths exercise’ is one such example (Mathieu and Muir 158). Britt et al.’s study of 277 community college students provides comprehensive evidence of the efficacy of such mindful breathing exercises on reducing students’ AWA. Such an activity can also be complemented with stretching exercises and walking. Gupta also uses relaxing ambient music as students enter the classroom as this kind of music has been shown to have therapeutic effects. Perry provides useful examples of what such trainings might look like. Designing such training sessions and interventions in a community-driven rather than a top-down manner would also engender the kind of social relationships that many of our participants noted are essential to helping them deal with their AWA.

Using data from the impact of such exercises on students’ well-being, learning, and transfer, stakeholders in graduate programs can then advocate for and initiate changes to the conditions that lead to AWA in the first place. Driscoll and Powell’s study is a good example of such work. In terms of the kinds of institutional and disciplinary reforms that enable well-being, redefining the goals of academic writing and the measurements of success is often a useful starting point. For example, Muir and Mathieu advocate for “an approach toward teaching writing that redefines terms such as rigor and success in more compassionate and health-focused ways” (154). This could include expanding learning outcomes of writing courses beyond rhetorical skills towards helping “students develop strategies for managing stress and increasing well-being” (Campbell, 2016). Such learning outcomes can be operationalized in many ways. Martin does so through a writing class themed around well-being, and Trejo et al. present a wonderful model of how such goals can be materialized for marginalized graduate students through informal writing groups outside classrooms.

Supporting these learning outcomes would involve not just new kinds of assignments though but also new paradigms of assessment as well. By using literature on anti-racist assessment practices such-as contract grading (Inoue, Kryger & Zimmerman), graduate programs can radically reform their evaluation practices. This should also involve revising existing classroom genres like syllabi and assignment sheets to create anti-racist genre systems. Graphenreed and Poe recommend making revisions such as adding community statements in syllabi that explicitly foreground commitment to social justice.

Conclusion

Our goal in conducting this study is to deepen our understanding of graduate students’ experiences with AWA and provide more targeted strategies that instructors, students, and graduate program directors can use in their classes and programs. Because our current study involved a limited group of graduate students, we can only identify the trends that we found emerging from our data that might lead to new areas of inquiry. We especially noticed the prominence of procrastination in responses from graduate students. But we also realized that when procrastination is reframed, perhaps by using different terms such as “taking a break” or “stepping away” from a project, then it becomes a healthy self-care strategy. The labels that are used for different causes, effects, and strategies can be powerful because of their connotations, and studying the ways that graduate students use and interpret these labels could be an important area of future study.

We also urge future studies to consider the impact of intersectionality on reported causes and strategies and also the impact of the researchers’ interpretations of the responses. Some researchers have done so by focusing on specific demographics. Bloom, for example, has looked at the role of gender on AWA, while McAllister et al. studied African-American men’s writing anxieties in college. Building on such initiatives, we call for more comprehensive exploration of the intersection between AWA and systemic inequities in higher education. We acknowledge that our own limited perspectives impact our assumptions about how we group different responses and the relationships we see between them. Just as we identified a need to gather a range of graduate student perspectives to better understand AWA, we also urge writing scholars to examine these data and gather additional data so that we can better understand–and mitigate the negative impacts of AWA.

Acknowledgements

We are really grateful to Dr. Aimee Mapes’ guidance that helped us with our IRB and survey instrument development process. We are also immensely grateful to Dr. Jameson Lopez for sharing his expertise on quantitative survey design.

Works Cited

Batzer, Benjamin. Healing Classrooms. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://compositionforum.org/issue/34/healing-classrooms.php.

Bloom, Lynn Z. Why Graduate Students Can’t Write: Implications for Research on Writing Anxiety on Graduate Education. Journal of Advanced Composition, vol. 2, no. 1/2, 1981, pp. 103–17.

Britt, Megan, et al. Effect of a Mindful Breathing Intervention on Community College Students’ Writing Apprehension and Writing Performance. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, vol. 42, no. 10, Oct. 2018, pp. 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2017.1352545.

Campbell, Jennifer. Talking about Happiness: Interview Research and Well-Being. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://compositionforum.org/issue/34/talking-happiness.php.

Carlo, Rosanne. Countering Institutional Success Stories: Outlaw Emotions in the Literacy Narrative. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://www.compositionforum.com/issue/34/countering.php.

Cassady, Jerrell. Anxiety in Schools: The Causes, Consequences, and Solutions for Academic Anxieties. Peter Lang, 2010.

Cheng, Yuh Show. A Measure of Second Language Writing Anxiety: Scale Development and Preliminary Validation. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 13, no. 4, Dec. 2004, pp. 313–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2004.07.001.

Daly, John A., and Wayne Shamo. Academic Decisions as a Function of Writing Apprehension. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 12, no. 2, 1978, pp. 119–26.

———, and Deborah A. Wilson. Writing Apprehension, Self-Esteem, and Personality. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 17, no. 4, 1983, pp. 327–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40170968.

———, and Michael Miller. The Empirical Development of an Instrument to Measure Writing Apprehension. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 9, no. 3, 1975, pp. 242–49.

DeBacher, Sarah, and Deborah Harris-Moore. First, Do No Harm: Teaching Writing in the Wake of Traumatic Events. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, http://compositionforum.com/issue/34/first-do-no-harm.php.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Roger Powell. States, Traits, and Dispositions: The Impact of Emotion on Writing Development and Writing Transfer Across College Courses and Beyond. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://www.compositionforum.com/issue/34/states-traits.php.

Evans, Teresa M., et al. Evidence for a Mental Health Crisis in Graduate Education. Nature Biotechnology, vol. 36, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 282–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089.

Goodman, Sheryl Baratz, and Carol Cabrey Cirka. Efficacy and Anxiety: An Examination of Writing Attitudes in a First-Year Seminar. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, vol. 20, no. 3, 2009, pp. 5–28.

Graphenreed, Tieanna, and Mya Poe. Antiracist Genre Systems: Creating Non-Violent Writing Classroom Spaces. Composition Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, 2022, pp. 53–76.

Gupta, Anuj. Emotions in Academic Writing/Care-Work in Academia: Notes Towards a Repositioning of Academic Labor in India (& Beyond). Academic Labour: Research and Artistry, vol. 5, 2021, pp. 107–36.

Huerta, Margarita, et al. Graduate Students as Academic Writers: Writing Anxiety, Self-Efficacy and Emotional Intelligence. Higher Education Research & Development, vol. 36, no. 4, June 2017, pp. 716–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1238881.

Inoue, Asao B. Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future. The WAC Clearinghouse/Parlor P, 2015. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2015.0698.

Kryger, Kathleen, and Griffin X. Zimmerman. Neurodivergence and Intersectionality in Labor-Based Grading Contracts. Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 13, no. 2, 2020, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0934x4rm.

Martin, Heather. WELL 2100: Writing for Wellness. Composition Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, 2022, pp. 170–178.

Martinez, Christy Teranishi, et al. Pain and Pleasure in Short Essay Writing: Factors Predicting University Students’ Writing Anxiety and Writing Self-Efficacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, vol. 54, no. 5, Feb. 2011, pp. 351–60. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.54.5.5.

McAllister, John W., et al. The Writing Apprehension of African American Men in College: Recommendations for the Professoriate. Race, Gender & Class, vol. 24, no. 3–4, 2017, pp. 119–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26529226.

Micciche, Laura. Doing Emotion: Rhetoric, Writing, Teaching. Boynton/Cook, 2007.

Miller-Cochran, Susan, and Stacey Cochran, editors. Advocating for Writing and Well-Being. Composition Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, 2022, pp. 9–15.

Muir, Angela, and Paula Mathieu. Contemplative Pedagogy for Health and Well-Being in a Trauma-Filled World. Composition Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, 2022, pp. 154–69.

Neff, Kristin D. Self-Compassion, Self-Esteem, and Well-Being: Self-Compassion, Self-Esteem, and Well-Being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, vol. 5, no. 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J., and Kathleen M. T. Collins. Writing Apprehension and Academic Procrastination among Graduate Students. Perceptual and Motor Skills, vol. 92, 2001, pp. 560–62.

Pennebaker, James W. Writing About Emotional Experiences as a Therapeutic Process. Psychological Science, vol. 8, no. 3, May 1997, pp. 162–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00403.x.

Perry, Alison. Training for Triggers: Helping Writing Center Consultants Navigate Emotional Sessions. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://compositionforum.org/issue/34/training-triggers.php.

Ricker, Mari, Victoria Maizes, et al. A Longitudinal Study of Burnout and Well-Being in Family Medicine Resident Physicians. Family Medicine, vol. 52, no. 10, Nov. 2020, pp. 716–23. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2020.179585.

Ricker, Mari, Audrey J. Brooks, et al. Well-Being in Residency: Impact of an Online Physician Well-Being Course on Resiliency and Burnout in Incoming Residents. Family Medicine, vol. 53, no. 2, Feb. 2021, pp. 123–28. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2021.314886.

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitiative Researchers. 3rd edition, SAGE, 2016.

Sanders-Reio, Joanne, et al. Do Students’ Beliefs about Writing Relate to Their Writing Self-Efficacy, Apprehension, and Performance? Learning and Instruction, vol. 33, Oct. 2014, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.02.001.

Trejo, Cynthia D., et al. Critical Feminista Dimensions to Informal Writing Groups for Women of Color Pursuing Doctoral Degrees. Composition Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, 2022, pp. 211–217.

Weisser, Christian, et al. From the Editors. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://compositionforum.com/issue/34/from-the-editors.php.

Yagelski, Robert, and Daniel Collins. Writing Well/Writing to Be Well: Rethinking the Purposes of Postsecondary Writing Instruction. Composition Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, 2022, pp. 16–33.

Academic Writing Anxieties from Composition Forum 54 (Summer 2024)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/54/academic-writing-anxieties.php

© Copyright 2024 Anuj Gupta and Susan Miller-Cochran.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 54 table of contents.