Composition Forum 48, Spring 2022

http://compositionforum.com/issue/48/

A Conversation on Race and Writing Assessment with Asao B. Inoue and Mya Poe

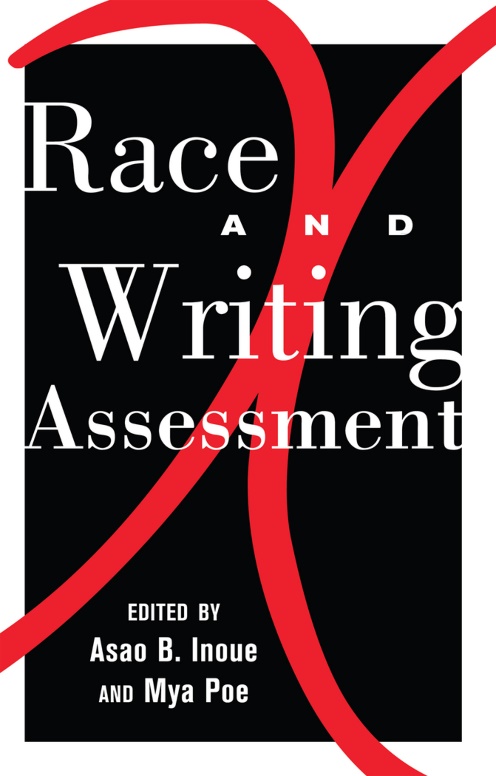

Asao B. Inoue and Mya Poe published Race and Writing Assessment almost a decade ago. Race and Writing Assessment encourages teachers to explore how writing assessment affects culturally and linguistically diverse students. Winner of the 2014 Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) Outstanding Book Award, their edited collection was one of the first of its kind. It offers theories, models, practices, and frameworks attuned to racial diversity and helped launch a wave of conversations in writing studies intersecting race and assessment.

Race and Writing Assessment includes seventeen contributors and twelve chapters displaying a range of localized approaches to assessment. Throughout the collection, Inoue and Poe challenge teachers to consider the structural and systemic inequities and gaps on race in writing assessment research and practice. They ask, “Are our assessments affecting students differently? What kinds of changes might we make to existing practices to ensure that all students are assessed in a fair and culturally sensitive manner that is also context based? What kinds of data should we be gathering to answer these questions?” (1). Nearly a decade later, these questions seem just as relevant. Yet, in the past ten years we have also seen major changes in the field with calls for linguistic justice and antiracism in assessment, research, and publishing practices. Race and Writing Assessment captured a moment in the field. What has happened since then?

In May 2021, I asked Inoue and Poe if they’d be willing to chat about their collection. They generously agreed. The following interview covers a range of topics and ideas from Race and Writing Assessment, including the pushback they received in the publication process, the absent presence of race and racism in conversations around assessment at the time, the contribution the collection made to the field, how racial formation theory extended and diverged from traditional assessment research on validity and reliability, the need to rewrite program and classroom outcomes, and what future directions writing studies can take with research on race and writing assessment. What follows is a slightly edited conversation with two wonderful teacher-scholars.

Shane A. Wood (SW): Race and Writing Assessment was published almost ten years ago in 2012. I was hoping you could talk about its exigence. Was there a particular aha moment early on where you felt like this collection had the potential to make an impact on teaching and assessing writing?

Asao B. Inoue (AI): I think, certainly, Shane, we hoped it would. And we certainly saw a gap and a need in the field of writing assessment to focus on race and racism. But when I think about this question, I'm actually thinking about—Mya, you probably remember this differently—one of our early conversations at the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC). Maybe it was the one in New York. We had lunch and we sat down and we were really thinking about this idea. We had already had some emails and we had talked about each other's work a little bit. It was one of the earlier times that we had met in person, I think. I remember thinking at that time that nobody had done anything like this yet.

And we could be the first to do this. It was really important, and both of us happened to have the right kinds of backgrounds to be able to think about this question of race and writing assessment. So we had all these different ideas about what we might try to do. And then, of course, as that first year or two went by, we had some troubles or some difficulty getting the voices we thought we wanted to get, and we thought we needed to get. Then there was a reviewer who just said, “You guys just can't pull this off.” And we were like, “That's disappointing.”

But we did. So what I'm remembering about this, and beyond what we wrote in the introduction, was that I had found this really cool person, Mya, that was doing all this great stuff in a faraway place. Far away from any place that I'd ever had studied or lived. I was really excited to get to work with her and to get to do this work that I knew that we both were deeply invested. So for me, it was more of like a human connection because up to that point I really had nobody in the field, as early as I was in my career, who was really thinking about these same kinds of questions and trying to do the same kind of work on writing assessment. It was nice to find a kindred spirit, if you will, who was as interested as I was in doing this work.

Mya Poe (MP): Yeah, when we met, I thought, “Holy moly. There's somebody who is thinking in the same ways.” Before I met Asao, I felt like I had hit a wall. I would try to go and present these ideas and there would be this incredible pushback from the old guard. Meeting Asao gave me new optimism about the work.

I went back and read some of the reviews of our book proposal for this interview.

AI: Oh, no.

SW: Can you share?

MP: One of them was like, “No, all of these issues have already been resolved in the measurement world. You are doing nothing new” Now, ten years later as I am re-reading that review, I'm thinking, “That's really interesting,” because a reckoning is beginning to happen now in measurement. It was just the hubris and the condescension in the reviews. It was really infuriating.

I think it's also important to remember that the original title of the book was Race and Racism in Writing Assessment.

AI: That's right.

MP: We had to take out the word “Racism” to get the book in print.

Part of the strategy besides joining forces with each other was that we also realized we needed to enlist other people in this project if we were going to make things stick. I think it really speaks to the power of collaboration if you want to try to make change.

SW: Yeah, and if my memory serves me right, I remember having conversations with you or Asao about the book being rejected its first time, right?

MP: It was rejected two times.

SW: Twice?

MP: I'm pretty sure the first time it was rejected, one of the people who rejected it was the person who wrote a book review of it after it was published.

AI: I think you may be right.

SW: You mentioned earlier how this collection was one of the first to bring together race and writing assessment. It was one of the first to explicitly address the “absent presence” of race and racism in writing assessment, right?

AI: Yeah, I think that absent presence...I first noticed that in a graduate seminar on writing assessment I took with Bill Condon. I was a PhD student at the time, and we had all the literature that we were supposed to read. Most of them are still very good today, but none of them really were talking about this thing that I was clearly seeing from other courses and studies I was doing at the same time around race and racism. All I could see were the absences and presences: “How are you not talking about this when you're talking about this kind of holistic scoring, or you're talking about portfolios in diverse classrooms, or a writing program that's going to have different kinds of bodies in that program?” I didn't have all the ways to think about it yet, but I certainly had that general sense from [Catherine] Prendergast's early work on that absent presence.

MP: The initial ideas are certainly formulated in graduate school. I was taking a class with Sonia Nieto on culturally responsive pedagogy, where I was reading scholars like Gloria Ladson-Billings. Also, I was taking classes on nineteenth century African American literature and Native American literature. I was moved by the rich social commentary from writers like Pauline Hopkins and Sarah Winnemucca. I wanted to read more writing assessment scholars write powerfully about racism. So, yeah, there was very much an absent presence.

Another reason I became interested in this work was for personal reasons. I grew up in a Northern suburb of Cincinnati. I went to a high school where I witnessed how assessment, curriculum, disciplinary policies, ability tracking, and so on create and sustain social structural inequalities. You see how, as a White person, you are advantaged by that system. For me, 50 years later, it’s compelling to see the legacies of bussing and integration. So, there’s an absent presence in terms of the academic sphere, but also from the personal sphere in that structural racism was obvious in the school system that I attended, but it was never openly discussed in school.

SW: Yeah, and the majority of scholarship on assessment prior to Race and Writing Assessment had been on concepts of validity and reliability. In what ways did you feel like the collection extended these conversations, but also diverged from them? For example, I feel like there's something to be said here about how this book addresses “fairness” in writing assessment.

MP: I think the collection was working with [Samuel] Messick's ideas about social ramifications of validity. I started to drift towards fairness in about 2013 when the Standards for Educational Psychological Testing were revised because there was a promise that fairness was going to be put on equal footing as validity and reliability. I think fairness is a powerful idea, but it's really never had the kind of attention that validity has had. Validity was and remains the controlling theoretical lens in measurement.

I've also become interested in the concept of justice and extending that conversation beyond John Rawls, that is, really thinking about how the many conversations about justice within BIPOC communities are important in how we think about assessment and what we do with assessment in the world. For example, Stafford Hood and Rodney K. Hopson point out that fairness has a critical history in measurement through the work of scholars like Asa Hilliard.

AI: I think those early conversations around validity and reliability, at least for me, just were missing things, as good as they were. I mean, in a writing assessment context I was reading Kathy Yancey’s articulations of validity and reliability, and then moving back to Messick and [Lee Joseph] Cronbach. All I could see in those were these positivist assumptions about intelligence and social dimensions of students that end up having consequences in all kinds of tests. My readings got me thinking about the social consequences that discourse and its judgment ends up having and the influence it has on teachers. That is, when you grow up in systems that accept things like large-scale testing because you don't really understand the mysticism of it, because it's complicated and it's very scientific, you just have to accept that these scientists and educational statisticians understand adequately enough what they're doing. Doing this means you accept part of those biases, without understanding fully the biases, when you go and grade in your classroom.

I was thinking about issues of fairness in classrooms, because to me, that felt like a project I had always been working on. And it agreed very much with the kind of political things that I wanted to do as a scholar and teacher and that I felt I could have the most impact in. I absolutely agree with Mya in terms of thinking about, “How do we do that work better?” Not just from the White, Western philosophical traditions of what fairness has been, as valuable and helpful as those traditions can be and are. There are other conceptions of it as well.

SW: I want to spend time talking about how you frame “race.” In the introduction, you write about how the concept of “racial formation” better serves writing assessment scholarship and this helps you explain what racism is and is not: “If racial formations are about historical and structural forces that organize and represent bodies and their lived experiences, then racism is not about prejudice, personal biases, or intent. Racism is not about blaming or shaming White people. It is about understanding how unequal and unfair outcomes may be structured into our assessment technologies and the interpretations that we make from their outcomes.” Can you talk about what racial formation theory affords writing teachers, and/or what you were hoping racial formation theory would allow teachers to better understand about race and writing assessment? And then, maybe you could talk about the importance of investigating “unequal and unfair outcomes” and rewriting them?

MP: We used racial formation theory when we published Race and Writing Assessment because racial formation theory helped us explain race as a historical project, but it didn’t help us explain so much how it is baked into systems.

I don't know today that we would necessarily rely on racial formation theory. I think instead we would go to systemic racism, “which is a social science theory of race and racism that elucidates the foundational enveloping and persisting structures, mechanisms, and operations of racial oppression that have fundamentally shaped the United States past and present” (Feagin and Elias, 2013). And regardless of your position, you're benefiting or investing in this or participating in this, and you have a responsibility to call questions, to raise issues, and so on, regardless of where you are in the system.

In regard to the second part of the question about outcomes, I'm going to quote something from Dave Eubanks, which I think is good. He says, “Learning outcome statements are just crude placeholders for describing complex human behaviors. There is no magical power in view by getting the words just right or finding the right verbs to say what it is you want to say.” Outcomes end up being important because the machinery of program assessment in accreditation is based on “outcomes, outcomes, outcomes.” Outcomes have this weird, unnatural force in the higher education ecology because of accreditation. A lot of programs rush outcomes and end up replicating structural inequality. They don’t try to use the power of outcomes for anti-racist change.

AI: Yeah. I'll just say a couple of words about racial formation theory. What I have to say really agrees with what Mya was saying, but my sense of it was that from the reviews we got from proposals and other places, we were anxious. I think, at least I was, about the reception. Like, will people be willing to listen to this? So at that time, at least from my view, the structural critique of racism was not as okay to offer as it is today. I think that most people who understand and studied critical race theory or other ways of understanding race and racism in the world, even Omi and [Howard] Winant would have agreed, racism is structural. It is systemic in institutions, et cetera, that’s probably the better way to think about it.

But, the entry point is, race is an evolutionary thing that changes with people because we define it and we make it valuable in the world, and then it forms and reforms. I think that was a friendlier, perhaps even a foreign concept, but a friendlier concept than saying we are stuck in White supremacist systems that will make us be White supremacists in our outcomes and in our classrooms. That is just going to be a hard pill to swallow.

In terms of the outcomes and the importance of investigating and rewriting programmatic or classroom outcomes, absolutely. I think in addition to what Mya said...when I think of outcomes, they are black holes. Everybody is attracted to them for all kinds of important reasons, but also all kinds of really bad reasons. When I think of outcomes, I think of two kinds of outcomes. One, is predetermined ones beforehand, before you even meet any students, before you know what's going to happen in the world. And then outcomes that are more organic and that come out of a community doing stuff. The second kind I find much more valuable because they tend to be more democratic, they tend to be more surprising and interesting, and they invent new things and new ways of seeing, thinking, understanding, et cetera.

So, when I think of outcomes, I often think that they're quite limiting. They artificially box in, as much as all the other problems that Mya was describing and what Eubanks tells us. They also just go about the learning enterprise as a closed system. One that says, “We don't want anything other than these things.” And so, we have to start asking, “Well, where did those things come from? Who tends to have benefited in history when those things are the things that are valued most? What groups of people, or what racial formations, or gendered formations, or intersectional formations in the United States create the values and outcomes that we use in our classrooms?”

So, absolutely, I think we should probably be inventing outcomes—all our classrooms might invent outcomes—that is, our jobs might be to understand what outcomes we end up getting in classrooms and how valuable they can be and what they can do for us as a society or school or university in the future. This is outcomes that are NOT predetermined ahead of time.

SW: I’m sitting here thinking about “predetermined outcomes,” or this set of outcomes that are sort of baked in a syllabus that get taken into a class. It almost doesn’t make sense to use predetermined outcomes when we have different pedagogies and practices, and different institutional contexts and students. How can we cultivate more collaborative, organic conversations about learning outcomes?

AI: I think that's what I value about Bob Broad’s work in dynamic criteria mapping so much. It’s an inductive process that can open up ideas and it's highly flexible in terms of what version or what way you might want to try to do it with whomever, whether it's a group of teachers, group of students, group of admission counselors, whatever we're talking about. I like that flexibility in that system and its inductive organic-ness, what it produces and shows us. It's not making judgements on people and then slotting them into pre-defined categories, then making decisions about students. It’s understanding judgement and its relation to what we value or understanding that what we value makes in large part what we think we see in student writing.

MP: I think we also forget history. Having outcomes baked into educational systems took off in the 1990s during the Clinton-era. Outcomes then then got mapped onto No Child Left Behind. We've forgotten that they arose at a particular moment when discussions about “accountability” were at the forefront. And that they arose for a particular kind of purpose--a belief that you could define and deliver an educational product and have evidence of that delivery.

The other thing I find interesting about outcomes is when we go to actually assess them, as [Chris] Gallagher argues, it's not just that certain things aren't valued, it’s that outcomes assessment doesn’t address failure very well. Because all the weight is placed on “meeting” outcomes--and real consequences for not meeting outcomes--there are only simplistic responses to failing. People don't want to have risky outcomes that potentially open up conversations about the messiness of learning.

SW: One of your aims in Race and Writing Assessment was to “invite readers to consider how a focus on racial identity allows them to see their assessment practices in new ways.” Since 2012, there’s been a lot of scholarship that has taken up this call to reconsider and reimagine classroom and program assessment through fairness and antiracism and social justice. Which is one reason why I see this collection as a key, pivotal text in the history of our field. I think it has helped shape a lot of conversations over the last ten years.

AI: I think our collection was also a product of us being in the right moment at the right time to be able to do this work and then get it published and so forth. I don't want to say like, “Oh, well, without this, none of this other stuff could have happened. We wouldn't have the attention to race or racism in writing assessment, more generally, than we do today, however major or minor we think it is.” I will say that after this collection, there was a greater attention to do this work by more and more people. It probably helped that it got an award. That doesn't ever hurt. In fact, in some ways it legitimizes things in weird ways. I have ambivalent feelings about that.

But I do think that it was important to have it be validated by the discipline in some ways, for no other reason except to say that other people besides Mya and me and our contributors find this topic important, and that more work should be done, because this is just the first baby step and there are other folks after us that will make bigger strides than we can here given that there’s a door that’s being cracked open. So I feel like that was important to do. I think that's also just the nature of how new ideas or different ways of seeing things happen in disciplines. Because disciplines and disciplinarity tend to be, at least from my view, a pretty conservative force that tends to want to preserve itself, or traditions for good reasons and bad reasons.

MP: Thankfully, we didn't give up on the project. There was a conversation about that after the second rejection. Like, “Should we just stop?” Len Podis with Peter Lang took us on. But I will tell you, I got in so much trouble for publishing this collection through Peter Lang. I was untenured and my department reviewers were like, “This is not only not going to help you, it's going to harm you.” So, anyway, I'm just saying this for people out there thinking about what they may be working on now. Believe in your gut, go with that, even if the people around you are telling you, “No, your project doesn't have value.”

All this work certainly could not have existed for me without Arnetha Ball’s work and Geneva Smitherman's work--all the work on critical race theory and culturally relevant education by Gloria Ladson-Billings.

I feel like one of the things that Race and Writing Assessment did is it took away discussions about race and racism from the “special populations” section of books and made these issues more central to the field. I think there's no one in the field today who can think about placement testing in the ways the field did twenty years ago. You can't purchase a test like Accuplacer and think, “Oh, it's okay. And it's fair.” You have no excuse now. It's just not acceptable.

SW: How did it feel receiving the 2014 Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) Outstanding Book Award after the pushback and rejections?

MP: There's a picture of us and the smile on our faces is worth a lot.

AI: Yeah, yeah. It says quite a bit. Thanks for reminding me of that. I think that certainly helped me feel better about all the work that we had put into it and the delay and the rejections because I know... I'm sure that most all academics understand what rejection feels like and what it means because we all have to go through it at some point. And even projects like this, which today I think most would say are clearly important and ought to be considered, didn't start that way and there was uncertainty about what was going to happen. I think it was really validating in many ways.

It was important and it helped me say, “Oh, I think I can keep doing this work,” and as Mya was alluding to with her colleagues, it helped me feel like I was not risking a career suicide and falling on my sword of antiracism because it did feel like that for some time. My career has been divided by this book. Before the publication of it and after, in terms of who would listen to me and on what terms would they listen. That has been good for the antiracist cause, I think.

MP: Yeah. I think about the people who were along with us in that journey; it was a lot to ask them to stay with the book for all that time. I thank them for sticking with us and not taking their work elsewhere. It gave me confidence in the power of doing collaborative work, to advance this kind of cause in the 2016 College English special issue we did, our second collection, and future work. You have to bring lots of different people to the conversation, two-year college people, non-tenure track people, not just people from R1s. You don't perpetuate the same gatekeeping that kept you out. People may take your work. People may reject your work. Fine, but let's just keep this conversation about antiracism and justice going.

SW: In this historical moment with social justice movements like Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate, I feel like there’s an opportunity to consider how our undergraduate and graduate students are experiencing language and writing and reading and activism, and an opportunity for us to rebuild systems and structures.

I’m reminded of Mike Rose’s Lives on the Boundary which won the first CCCC Outstanding Book Award in 1991. I feel like Lives on the Boundary and Race and Writing Assessment speak to one another in interesting ways because they say something about educational systems and how policies and structures present challenges for marginalized students. I think, personally, we need more work in writing assessment research and theory that focuses on undergraduate and graduate students’ lived experiences. What kinds of future directions do you hope to see the field take with race and writing assessment?

MP: Thanks for that generous connection to Mike Rose’s work. I think that students’ lived experiences are some of the most powerful evidence we can have. Students’ stories are also some of the most undervalued evidence in assessment research. If you look at outcomes assessment, direct evidence is valued over indirect evidence. Direct evidence is scoring data, which is not done by the student; it's done by raters. Indirect evidence, which can be students actually talking about their own experiences with assessment, is not considered as “good” of data as those scores. That’s nonsense. I think the best data that we can gather on what our practices are doing actually is evidenced through students’ experiences. We need those experiences to make structural change. So, yes, Mike Rose connects with us very much in that way.

In regard to the second part of your question about where the field would go, I looked back on the book, and there's certain chapters I carry with me today as I think about the future of the field. Really, all the chapters continue to inspire me. For today, I think about Chris Anson’s chapter in which he talks about WAC’s colorblind, helper identity, and how the newer work on Antiracist WAC by Genevieve García de Müeller is challenging that identity.

Today, I carry with me [Élisabeth] Bautier and [Christiane] Donahue’s chapter about PISA testing in France, and the lack of culturally relevant approaches in international testing. The other thing I take from their chapter is the idea of missing datasets. As they explain, in France, you can't ask a student about their race. Instead, French researchers use students’ zip codes as a proxy for racial identity.

For additional work I'd really like to see people critique the whiteness of accreditation boards. If some of this work is going to have to happen, it needs to be valued at the accreditation level and brought down. I also would like continuing critiques of algorithms for automated feedback of student writing. So many algorithms are just junk; those programs are targeted at students at community colleges and students who are most likely to be the objects of algorithmic racist logics.

AI: Yeah, I'm so glad that you called my attention to Lives on the Boundary. Because in ‘93, I met Mike Rose. He came to my alma mater, Oregon State University, to give a talk to this filled ballroom. He may have been talking about Lives on the Boundary. I don't remember. But what I remember is there's literally hundreds of people in this ballroom at the end of his talk, and everybody wants to shake his hand and say a few words to him. And he's so patient and so giving of his time. He sits there for 30 minutes just talking to each person in a very human and teacherly, wonderful way. And he did that with me, and he shook my hand.

I remember him listening to...I had this weird question. I don't remember what it was, but it was just something that was less of a question and more like, “I want to say something to Mike Rose and just sound smart,” like a young person would do. I did that and I regret that now, but I don't regret meeting him and how wonderful of person he was. I can see how Lives on the Boundary and the effect of, as you make present for us, Shane, stories of students’ experiences in classrooms and in assessment situations is so vital to us doing assessment better. But I also think that we might be able to do better than that. That is, when I think about what happened...if Mike Rose’s Lives on the Boundary was so paradigm shifting, or so good—and it was, why didn't we change?

Why did we still need another book? And why do we still need more? So, this is not a mark against Mike Rose and his excellent work and excellent scholarship. It’s to say, “It takes even more than that, unfortunately.” It takes more than being compassionately attentive to students’ voices. That even isn't enough. So I wonder what is the magic ingredient? Well, I think one part of that ingredient might be that we have to put those students’ stories of their experiences in school, for instance, in conversation with the structures and the disciplines and the institutions, institutional histories, that make them who they are, and that make the context in which they have to operate around. And then we start to see more of the unfairness. Then we start to see more of the racism and we start to see more of the White supremacy, and we'll know better what we can do beyond.

Otherwise, we leave it at that personal level which is almost the same paradigm as our needing to...Mya and I needing to start with “racial formation theory” and not with some of these other more structural kinds of theories that really point to the problem, right? So I think that, for me, is a really important challenge for us moving forward, all of us, whatever corner of composition studies or writing assessment research we’re doing. The possibilities are reinventing how we can use those student stories, which are so vital to us, as well as teachers’ stories. I'm not talking about researchers; I'm talking about teachers. I don't know how to access that fully. But most teachers who teach writing don't publish in writing studies. And they ought to be heard and they ought to have a voice in some way. And the question is, how do we do that?

I have come back to just about all of the chapters in this book in the last decade. They all have some value to me in different ways. Some have been more important for me only because of the conversations that I tend to have at this moment. I never thought, for instance, not because it was a bad chapter, it was a great chapter, that Valerie Balester’s chapter would be something that I would still be talking about with people because they want to talk about rubrics. Because that's their interests, right? That's one that I come back to because she did some really nice work there and it remains important, it offers us some important questions to ask, we might frame things a little differently today because we have different things to frame with, but it's an important one to ask. The same goes with Diane Kelly-Riley’s really good chapter [on validity and shared evaluation], which I come to find more value and more value the more times I read it. Again, all of them are important in different ways.

SW: Thanks so much for having this conversation with me, and for doing this work. I’m so thankful for you both.

MP: Thank you, Shane. One of the best benefits for me out of all of this work is the people I've met--people like you, Shane, and Asao. I appreciate folks who want to have these conversations. I appreciate folks who help me extend my thinking, see where I err, see where I can do better. That is one of the things that continually gives me hope, despite those early reviews!

AI: Absolutely. I agree with what Mya said. It's the relationships and the people that I meet that help keep me going when things get hard and when stuff happens professionally or otherwise. I get to meet great people like you, Shane and like Mya, and I get to have long relationships that I get enriched by. Which is the case for both of you, whenever I leave exchanges with you both, I feel like I just cheated the universe. I’m given all these riches, and I’m not doing enough to give back.

One of the things I really value in my journey, even before this collection, is the really important people I get to meet. And Mya is certainly at the very top of that list in terms of important people that helped shape who I am and what I think about and how I think about things. I really didn't do a lot of collaboration before this because the field didn’t really value the kind of work I wanted to do as much. But collaboration is so important to innovation and opening up ideas. I'm really appreciative of all of that.

Works Cited

Eubanks, David. Guest Post: Weaponized Learning Outcomes. Inside Higher Ed. 2013.

Feagin, Joe and Sean Elias. Rethinking Racial Formation Theory: A Systemic Racism Critique. Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 36, no. 6, 931-960, 2013.

Hood, Stafford and Rodney K. Hopson. Evaluation Roots Reconsidered: Asa Hilliard, A Fallen Hero in the ‘Nobody Knows My Name’ Project, and African Educational Excellence. Review of Educational Research, vol. 78, 410-426, 2008.

Inoue, Asao B., and Mya Poe. Race and Writing Assessment. Peter Lang, 2012.

Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. Racial Formation in the United States. 3rd ed. Routledge, 2015.

Poe, Mya, and Asao B. Inoue. Special Issue: Toward Writing Assessment as Social Justice. College English, vol. 79, no. 2, 2016.

Rose, Mike. Lives on the Boundary. Free Press, 1989.

A Conversation on Race and Writing Assessment from Composition Forum 48 (Spring 2022)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/48/asao-inoue-mya-poe-interview.php

© Copyright 2022 Shane A. Wood.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 48 table of contents.