Composition Forum 53, Spring 2024

http://compositionforum.com/issue/53/

Terminology Matters: Taking Back Outcomes and Objectives in Composition Studies

Abstract: Even though learning outcomes have become an expected part of writing programs, how they are defined and subsequently used is often unclear. This study did a textual analysis of the terms used for outcomes on 42 universities’ first-year writing webpages. The study found that university writing programs use different terms for outcomes and define those terms differently across programs. The lack of clear definitions for outcomes across programs makes these documents difficult for writing programs, faculty, and students to use. Consequently, the author argues that composition studies needs to study definitions of outcomes terminology and then clearly define those terms in the materials programs, teachers, and students use. The author then presents suggestions for how programs and teachers might do this definitional work to make outcomes more useable for effective course design.

As universities become ever more corporate, the term neoliberal university highlights a “new understanding of higher education’s integral role in the present economic order” (Seal) and the reality that universities’ participation in that “economic order” results in ever-more mandates for assessment and evaluation. Throughout the university, outcomes statements are used to facilitate assessments, but several scholars critique outcomes and their connection to the corporate university and top-down mandates (Hussey and Smith, “The Trouble with Outcomes”), claiming they are difficult to implement (Allais) and too rigid (Hussey and Smith, “The Trouble with Outcomes”). Research acknowledges that instructors may resist outcomes for many reasons, such as it being unclear what outcomes actually predict and a concern that teachers have not been invited enough into outcomes discussions (Liu). As Ou Lydia Liu points out, too much attention has been focused on measuring student learning and not enough on how “outcomes assessment can be used by faculty members to improve instruction” (8). George D. Kuh and Peter T. Ewell mention something similar, stating how outcomes are mostly used for accreditation and “to a lesser degree, for revising undergraduate learning goals” (19). Because of these realities, outcomes can feel detached from actual instruction and instead seem more like a hoop teachers jump through to fulfill states’ programmatic requirements for college accreditation (Kuh and Ewell).

As such, it is unsurprising that Chris Gallagher describes the difficulties of and objections to outcomes implementation in English studies this way:

the time and effort we’re devoting to OA [outcomes assessment] might be better used in other ways, or that institutional OA risks compromising the academic freedom of our instructors and programs, or that our curricula are being narrowed to what is assessed, or that we’re experiencing standardization creep, or that bean counters will do nefarious things with the data we generate—but we’re pragmatic enough to get on with it anyway, lest direr fates befall us. (43)

Here, Gallagher points to two realities with outcomes in corporate higher education. First, faculty are frustrated by the top-down outcome mandates and consider them detached from learning. For example, Margaret K. Willard-Traub describes how it can feel like there is a “privileging of learning outcomes over the experience of learners; the consequential commodification of teachers, learners, and knowledge itself” (46). Feelings like those described by Willard-Traub make outcomes seem like by-products of a university that cares more about data and economics than actual teaching and learning, making outcomes emotionally charged rather than helpful class-planning documents to over-worked faculty. Second, faculty better write them and get it over with instead of dealing with the “direr” consequences of not having outcomes and not meeting the programmatic requirements to keep their positions.

While outcomes may be the result of the neoliberal university, outcomes are a reality composition studies must navigate if we don’t want others to define outcomes for us and if we want to make them worthwhile to our departments. In fact, as Liu points out, outcomes should be connected to improving teaching practices, and as a field that values good teaching, we should take the opportunity to make outcomes more worthwhile to our departments since we are required to use them. However, navigating how to make outcomes useful to our programs becomes impossible when we may not really know what outcomes are. Gallagher acknowledges this problem: “many of us in English studies [are]…not clear on the exact difference between an outcome and an objective” (42), a problem that is common throughout the university (Cohen and Manion; Rowntree). Scholars in fields as wide ranging as medical education (Harden; Prideaux) and food science education (Hartel and Foegeding) express the same concern about programs and teachers not knowing how to define outcomes language. Consequently, if programs defined outcomes terminology for their faculty and students in their outcomes statements, these documents could lead not only to less confused faculty, but could also be more useful to teaching and learning practices (such as outcomes informing backward course design).

I recently experienced the consequences of what happens when faculty do not know how outcomes are being defined. I was taking a course on how to teach online classes, and one of our assignments asked instructors to revise their objectives for the course they wanted to teach online. This assignment perplexed me because I had been taught in the past that objectives are for individual lesson plans, but I knew the teacher wouldn’t want my objectives for every class session. It was not until I saw what other students were submitting that I realized she wanted my outcomesfor the course and was defining objectives the same way I was defining outcomes. It was then I realized how many teachers and students may not know the definitions for outcomes and objectives, much less how to use them. Without a clear definition for what an objective was, the instructor and I did not have a common language about how to revise the statements and how to improve online course instruction. While I could have emailed the instructor and asked for clarification about how she defined the term objectives, I feared the instructor would think I was not a good teacher for not knowing what she meant by objectives. Other instructors may feel similarly, afraid to ask for definitions of terms because they do not want to appear incompetent. The same problem could happen when looking at outcomes statements online. Because so many terms are being used and many faculty do not know how to define the terms, teachers might not know what to do with the outcomes statements and decide not to use them when designing courses.

This is not the only consequence of using terms without a deep consideration of terms’ definitions and histories. Take for example Paul Kei Matsuda’s argument when discussing terminologies related to translingualism: “In order to fill the knowledge gap, composition theorists have attempted to borrow key terms and concepts from other disciplinary contexts, and, in the process, sometimes create an incongruent representation of those terms or concepts” (132-133). While not originally used for outcomes language, Matsuda’s argument applies to the terminology we employ for outcomes statements. Composition studies uses terms from other parts of education; however, the way we use these terms may not be an accurate representation of what they are or what we want them to be, particularly when using the term objectives as it has many different meanings and a complex history. (Definitions and histories for objectives and outcomes will be described in more depth in the next sections.) While terms for outcomes are varied and at times contradictory, understanding the history of those terms, what they mean, and what educational paradigms they align with communicate important messages to programs, faculty, and students.

While we may not have complete control over all the outcomes terminology we use because of state and local mandates, we do have the opportunity to take control of these terms at the disciplinary level and how we want to use them in our programs. If we, as writing programs and writing program administrators (WPAs), take control of outcomes terminology by acknowledging the histories of these terms (as outlined here and other scholarly works) and using clear definitions, we can do what composition studies does best: choose and define the right term for the right situation and apply that language to improved teaching practices. By understanding and defining these terms, composition studies can take control over outcomes language rather than letting it control us, communicate more effectively with faculty across different institutions, and use outcomes language in ways that create effective course design.

My Study

To respond to this definitional concern, I conducted a content analysis (Huckin) of forty-two universities’ online first-year writing outcomes statements as posted on English department or writing programs websites. I focused on first-year writing outcomes statements since most students are required to take a first-year writing course and because the majority of composition faculty have at one time taught the course. Because this study was part of a larger project about outcomes statements in composition studies, I picked universities that offer either a master’s or doctoral degree in composition and rhetoric as listed on the Rhetoric Society of America’s website.

To better understand outcomes statement language practices, I focused on the following questions:

What terms are used for course outcomes in first-year writing classes on university websites, and are these terms being defined?

How many programs reference the Writing Program Administration’s Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition (WPA OS), and if they do, do they use the same outcomes terminology?

To discuss my study and its implications, I will first give background on the history of outcomes assessment, definitions of outcomes terminology, and the WPA OS’s use of terms. I will then explain the study and some potential solutions for outcomes terminology moving forward.

Where Outcomes Assessment Comes From

Outcomes assessment began around forty years ago in the United States and has since continued to grow (Kuh and Ewell). Policy makers (both federal and state), the general public, and accreditation agencies “have increasingly been pressuring higher education to account for student learning and to create a culture of evidence” (Shavelson). This pressure to account for learning is often the result of the argument that because schools use government funding, they need to be accountable to the state and show students are learning what they are supposed to be learning (Kuh and Ewell). As such, departments, programs, and teachers need to have measurable outcomes that can be reported (Powell). However, because outcomes assessment mandates often come from those outside education, outcomes and their terminologies may be bound by state and federal governments with little say coming from those who actually work in education. Additionally, because of the focus on accountability, the second goal of outcomes, to inform teaching practices, often becomes the less important focus (Kuh and Ewell), which needs to be revised if outcomes are to become meaningful to education practices.

As such, I echo Richard J. Shavelson’s point that we should “take responsible steps to develop and measure the learning outcomes our nation values so highly.” While we must follow institutions’ accreditation rules, WPAs and faculty who work on the development of outcomes in composition studies have the opportunity to develop a language that helps faculty better understand what outcomes are, the terms being used, and how to make outcomes meaningful to teaching. In doing so, composition studies can have better charge of outcomes in areas we do control and better accomplish the second goal of outcomes assessment, which is to have outcomes inform teaching practices and move beyond just a form of accountability.

Defining Objectives and Outcomes

With so many terms related to outcomes, such as emergent versus intended learning outcomes (Hussey and Smith, “The Uses of Learning Outcomes”), aims, objectives (including terms like behavioral objectives, expressive objectives, and teaching objectives) (Allan), goals, competencies, purposes, “content standards, curriculum standards, accomplishments [emphasis added]” (Ascough) and more, even beginning to brush the surface of these terms and definitions can seem impossible to busy faculty. While the full range of definitions for so many terms are beyond the scope of this article and the use of most faculty, understanding the basic differences between outcomes and objectives, which are commonly used terms (Allan), and their histories can help not only reduce some of the confusion but also provide the necessary context before explaining my study.

First, the term objectives comes from Ralph W. Tyler’s influential 1949 work Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction. Tyler defines objectives as statements of what students have learned that can be measured. He argues that objectives should only be those things that are “obtainable” (37). Tyler focuses on what students will do with the content instead of just the content itself. According to Joana Allan, Tyler’s definition of objectives requires the institution to determine what students will learn, where students’ learning and teachers’ teaching are measured to determine whether instruction is effective.

Building on Tyler’s work, Robert F. Mager was a proponent of behavioral objectives. Behavioral objectives focus on the specific behaviors a student will demonstrate. In this definition, objectives are specific and detailed, including exactly what the student will do and how the student’s performance will be measured. Behavioral objectives often require the teacher or program to write lots of objective statements, which David Prideaux argues makes them too specific and inflexible. Merle Thompson, though, argues for the utility of behavioral objectives in first-year English in 1972, saying the “instruction at each point will be measurable” (11).

During the same period, Louis Cohen and Lawrence Manion discuss objectives that are not behavioral, exploring objectives that do not have strict explanations of what students will produce under certain conditions. Instead, they use the term objective to describe what the teacher and learners do in the classroom. These definitions and more led to additional terms to describe objectives. (See Allan for more information on these additional terms.)

In the 1990s, the term outcomes emerged in education literature. According to Prideaux, outcomes are not too different from Tyler’s original conception of objectives. Outcomes create backward design, determining what students will learn to do in a course before specific lessons are created. While the term outcomes, like objectives, will change over time, Prideaux discusses the fear that the definition of outcomes will change to focus too heavily on assessment and top-down mandates. For outcomes to be usable for teachers and students, the term cannot become inflexible, defined only in relation to meeting an institutional goal. As the term objectives demonstrates, when terms become overly laden with definitions and assessment specifications, they can become difficult for instructors to define and use in backward course design.

In discussing the differences between outcomes and objectives, scholars typically differentiate based on scope. As the term outcomes has started to replace the word objectives, it is helpful to think of outcomes as the term for broad goals and objectives the term for narrower classroom activities (Ferris and Hedgcock; Harden). In this way, it becomes clear which term informs course design and which informs individual teaching situations/lesson planning. It is important to note, however, that this definition does not hold true for all the literature (Anderson and Krathwohl; Maki; Hartel and Foegeding; Hussey and Smith, “Learning Outcomes: A Conceptual Analysis”). As Richard S. Ascough describes, this lack of consistency in the literature itself is confusing for many instructors. Without a common language, it is often difficult for instructors across the university to discuss course goals and design.

Because of the wide variety of definitions in the literature for these terms, I will go into depth on just two of the definitions of outcomes and objectives from Harden and Ferris and Hedgcock. First, Ronald M. Harden’s model describes outcomes as being broad, not as specific as objectives, and being more useable for planning and teaching purposes because outcomes focus on interrelationships of course content and are student centered. Outcomes are also more flexible, engaging, and useful for students and teachers because they lead to better course design, are not prescriptive, and are more likely to lead to faculty ownership.

Dana R. Ferris and John S. Hedgcock offer a similar definition of outcomes and objectives. In their definition, objectives are the smaller pieces of intended outcomes or goals, and intended outcomes or goals lead to backward design. In planning a class, an instructor would first look at the outcomes or goals, plan the course syllabus and calendar to meet those outcomes or goals, and then plan objectives for each course session. This distinction is important because if the terms were defined differently, they would indicate different steps in the process. For example, if a teacher had learned these definitions and saw the term objectives, they would assume there are also broader outcomes that are the necessary first step to creating a course. But if a program uses the term objectives for the broader statements, the instructor may not realize these statements are meant to help design the course. Instead, they may view the term more narrowly.

While the term outcomes was used most frequently in the study I conducted, I would like to touch on the terms goals and aims as they also came up in outcomes statements I researched, though I will not go into depth because of space considerations. Ferris and Hedgcock define goals as focusing on the broader concepts students will learn and state that goals “guide…ongoing assessment of student achievement, progress, and proficiency” (158). Regarding aims, Harden defines the term as synonymous with objectives. For the purposes of my study, I will define these terms’ scope using the definitions I have provided in this section, as seen in Table 1.

Term |

Broad or Narrow |

|---|---|

Outcomes |

Broad, used for backward course design, focuses on student learning throughout the class |

Goals |

Broad, focuses on broad concepts students will learn and is used for continual assessment of program |

Objectives |

Narrow, focuses on daily lesson plans and what students will do/show after each activity |

Aims |

Narrow, synonymous with objectives |

The WPA Outcomes Statement and Terminology

In response to the use of outcomes-based education in higher education, writing programs created the WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition in 2000. In Kathleen Blake Yancey’s description of the WPA OS’s creation, she discusses how the document responded to the concern that if writing programs did not define their own outcomes then someone without experience in writing would define the outcomes for them (Harrington et al.). For example, the WPA OS and the Council of Writing Program Administrators make it clear why they picked the word outcomes for the document. The WPA OS states that “This document intentionally defines only ‘outcomes,’ or the types of results, and not ‘standards,’ or precise levels of achievement.” By defining outcomes broadly, the WPA OS encourages flexible language practices and instructor autonomy, allowing instructors and programs to personally define more specific objectives. Harrington et al. discuss how the word outcomes indicates the expectations of the course while also giving specific schools the ability to use the WPA OS as they see fit for their program. Using the broader term outcomes allows for this coherence across multiple programs.

Research Methods

I conducted my study of universities’ first-year writing outcomes in Fall 2020. (Consequently, some of these webpages may have been updated since then.) I started with a Google search to find each university’s English department or writing programs website. Then, I navigated to the first-year writing page. When I reached this page, I looked specifically for the first-year writing outcomes. I only included outcomes statements from universities that specifically stated the information was an outcome, objective, goal, aim, or practice. All the programs I studied had created their own outcomes statements, and I used the outcomes posted for first and second semester first-year writing courses. Some universities had two sets of outcomes while others had only one. I used both if two were listed.

I did not use outcomes statements for basic writing and/or multilingual sections except in the case of a university in California. This university references the WPA OS and specific outcomes for the multilingual section; however, they do not offer a similar list for the mainstream section. Consequently, I pulled the terminology for outcomes from the multilingual section since it was not provided for the mainstream section. While the terms listed for a multilingual section may differ from a mainstream section depending on the university, I chose in this case to include the terms because it was one of only a few universities to reference the WPA OS, and I felt the data surrounding the WPA OS would be more accurate with more universities represented.

For the purposes of my study, I did a textual analysis of the outcomes terminology by marking which term the university used, if the university used more than one term, and whether the statement referenced the WPA OS. If a university used more than one term, I marked how the terms were differentiated or if they were used synonymously. If a university referenced the WPA OS, I marked whether the university used the term outcomes or a different term. I saved all data in a spreadsheet with the hyperlink of the first-year writing website.

Because this study looked at only forty-two universities’ outcomes in first-year writing courses, this data is specific to those universities. The inclusion of more universities’ outcomes could potentially change the data. Additionally, the dates of publication of each university’s outcomes were not included in this analysis, which may influence the language used as webpages are frequently updated. It is also important to recognize that websites can only say so much about a university’s use of outcomes and that website descriptions may not be precise representations of actual practices.

Results

Finding 1: Different Universities Use Different Terms

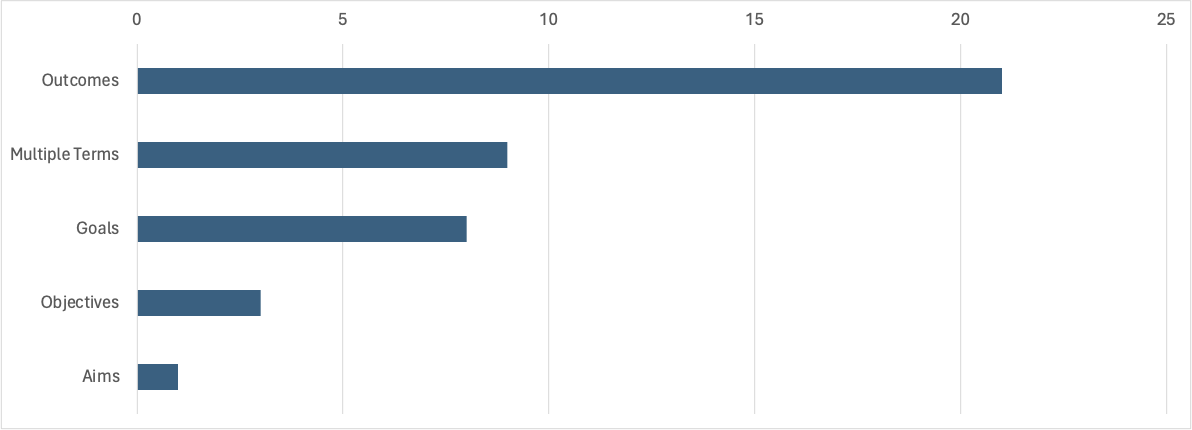

Across the U.S., universities do not consistently use the same terms for their first-year writing outcomes statements, which showcases why faculty are often confused by outcomes terminology. While the term outcome was the most popular term, several universities used the term goals or multiple different terms: twenty-one used the term outcomes, nine used more than one term, eight used goals, three used objectives, and one used aims. (See Figure 1.) Overall, the universities tended to use the webpages in similar ways despite using different terminologies to refer to the statements themselves. Typically, the statements offered something similar to the WPA OS in giving a broad direction for the course instead of a narrow one. While some statements included descriptions of the projects in first-year writing, the statements often did so in broad language.

Figure 1. Number of Universities that Use Specific Terms for Outcomes on Their First-Year Writing Websites

The webpages often addressed one of two audiences. The first audience was programs, administrators, and faculty. These webpages used third person, formal language and did not directly address students. They also frequently described how first-year writing related to other courses in the department. The second audience was students themselves, where the language specifically addressed students in second person and told them what they would learn. Because of the wide variety of potential audiences for these documents, the use of different terms may result in different reactions from the different readers. For students, the different terms used across universities probably does not matter a lot; however, in cases where a university used several terms on the same page, students may feel overwhelmed by what they are expected to accomplish in the course. For programs, the wide variety of different terms might make it difficult to communicate effectively with other programs that are using different terms. For faculty, confusion may occur if faculty members have past experience with terms and define them in opposite ways than the program is using them on the webpage. (Such as a teacher who personally defines outcomes broadly while the program uses outcomes narrowly.) This may be the case with faculty who have moved institutions, and their new institution uses a different term than their previous institution. In these situations, faculty may not be familiar with how their new university is using the term on their webpage.

Finding 2: Universities Are Not Using Terms the Same Way

Of the forty-two universities I studied, nine universities used more than one term on their first-year writing webpage. In these cases, I coded the text by marking whether terms were used synonymously, and if they were not, how the terms were used differently to communicate different meanings. As shown in Table 2, universities use a variety of terms on their webpages, indicating a lack of consistency across programs. Of the nine universities who used more than one term, each university used the terms in different ways, with some using terms interchangeably. In Table 2, I have included whether the terms indicated broad or narrow course expectations and which universities used terms synonymously.

University |

Terms Included |

Terms Used Synonymously? |

How Terms Were Used Differently |

|---|---|---|---|

University 1 |

-Outcomes -Goals |

No |

Outcomes: Broader Goals: Narrower |

University 2 |

-Outcomes -Goals |

Yes |

|

University 3 |

-Outcomes -Objectives |

No |

Outcomes: Broader (used as a heading for general education expectations) Objectives: Reference to WPA OS and specific items students would learn in first-year writing. |

University 4 |

-Outcomes -Objectives |

No |

Outcomes: Broader Objectives: Narrower |

University 5 |

-Goals -Practices |

No |

Goals: Broader Practices: How students will meet goals |

University 6 |

-Goals -Practices -Outcomes |

No |

Goals: Broadest Practices: Narrowest Outcomes: Linking Term |

University 7 |

-Objectives -Outcomes and Goals |

No |

Objectives: Broad learning in lower-level writing courses Outcomes and Goals: Narrower learning in specific courses |

University 8 |

-Goals -Practices and Knowledge Taught -Outcomes |

No |

Goals: University’s general education expectations Practices and Knowledge Taught: Broad definition of what students will learn Outcomes: Narrower definition of what students will be able to do |

University 9 |

-Goals -Objectives |

Yes |

|

Because the universities in Table 2 use multiple terms, their webpages are sometimes hard to read and make it difficult to know how to use the material to build a course. For example, University 6 in Table 2 uses the terms goals, practices, and outcomes. These terms are listed in columns with goals on the left-hand side, practices in the middle, and outcomes on the right-hand side. When looking at the chart on the webpage, it is unclear whether all the items listed are supposed to be considered outcomes or whether the goals and practices lead to outcomes. It seems as if goals are supposed to be the broadest, then outcomes, and then practices being the most specific. Because the term objectives is not used, it appears the term practices is used like the term objectives in this case. However, the chart is not organized that way. Without definitions of the terms and how they are supposed to be used, it becomes difficult to know what to do with the chart. For programs, it is unclear whether the columns in the chart highlight broad, programmatic goals or if they communicate more course specific goals. Does the program want to emphasize a narrow approach or a broad one? As teachers engage with the chart, they may not know which section of the chart to use to build the course. While the program probably decided to use a chart to help alleviate confusion and show both broad and narrow outcomes, teachers may be unsure whether they should use one of the columns or all three. Because some of the language is repeated in the column for practices and the column for outcomes, with the column for practices being the most in-depth, teachers may focus on just the practices column. Building a course from this document would be difficult considering the terms are not defined. Students who see this chart may wonder whether they are going to accomplish all these goals in one course or if the goals are supposed to overlap. In its current form, students might feel overwhelmed by the amount of material they will cover in the course.

For an example of a university that defines multiple terms on its webpage to make it clear which term is meant to be narrow and which broad, please see Appendix A. (I have put the information in a table for easier reading, but all language is directly from the source, University 4 in Table 2.) While this university did not provide a detailed definition for these two terms, they do make it clear that the objectives are meant to be more specific than the outcomes, which makes the document more usable because teachers can easily see how to build narrow daily objectives from the broader outcomes.

Finding 3: Not All Universities that Reference the WPA OS Use the Same Terms as the WPA OS

A total of six universities specifically mentioned the WPA OS as a guiding document for their statements. Of those universities, two used at least one term that was not outcomes. Using different terms when specifically referring to the WPA OS suggests these universities probably saw the terms they picked (objectives and goals) as being synonymous with the term outcomes. For example, the first-year writing webpage from University 3 in Table 2 references the WPA OS using the term objectives. The webpage starts with this heading before offering a bulleted list of what students will learn in the first-year writing course: “General Education Learning Outcome: Communication.” After this heading, the website offers a one-line statement about what students will learn. The webpage continues with the following: “Upon completing ENGL 1030, students will achieve the following learning objectives:”, after which four learning objectives for the course are listed. The webpage concludes talking about objectives with the following sentence referencing the WPA OS: “For a full list of learning objectives for First-Year Composition, please see the WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition” (includes a link to the WPA OS).

While this program probably uses both outcomes and objectives because of the need to distinguish between university general education and writing programs outcomes, the website demonstrates how without definitions, these terms can be confusing for faculty and students. Initially, it seems that the program defines outcomes as broader (relating to general education outcomes) and objectives as narrower (relating to first-year writing objectives); however, when referencing the WPA OS, the first-year writing objectives are seen as the same as the WPA OS’s outcomes. Without definitions of what constitutes an objective and what constitutes an outcome, the reader may not know how the university’s webpage relates to the WPA OS and whether the WPA OS should be viewed with the same broadness as the objectives on the webpage. For a clearer reading experience, this university could add a sentence or two explaining how the WPA OS relates to the terms used on the webpage, especially considering the university may have to use terms a certain way to meet the university’s general education requirement.

Moving Forward: How Composition Studies Can Re-Consider Outcomes Terminology

Overall, the findings suggest there is not a clear consensus for how terms related to outcomes are defined in first-year writing online outcomes statements. As such, I suggest the following ways composition studies can help define outcomes language for programs, teachers, and students, and how these changes impact teaching and learning practices in positive ways.

Defining Outcomes Language for Composition Programs

Composition programs need to understand and define the terminologies they use for outcomes statements for the program to know cohesively how to use these documents. As programs work to pick and define these terminologies, faculty within a program should be part of the discussion about terminology choices. In her discussion of terms in composition studies, Claire Lauer argues that “[d]efining terms is a situated activity that involves determining the collective interests and values of a community for which the definition matters” (225). Understanding the “collective interests” of faculty regarding outcomes terminology allows WPAs and faculty who work on outcomes statements to make better definitional choices while also demonstrating they value all faculty experience with outcomes. Because faculty come from all different teaching backgrounds, they may have experience with particular terms that inform how they react to them. They may also value some definitions over others. Soliciting the responses of faculty regarding term choice could help everyone feel involved with the outcomes and encourage them to use the documents they helped create. It also gives faculty the opportunity to express how they are currently defining terms and encourage positive communication about outcomes between colleagues.

At my institution, our writing program recently revised the outcomes statements for first-year writing. In this case, each group of faculty (adjuncts, TAs, lecturers, professors) were asked for their input on the outcomes statement and were given the opportunity to discuss the outcomes. Because my institution is large, issues regarding disciplinary divides were brought up, which is most likely going to be the case for other large programs. While this experience had its drawbacks, it also gave faculty a way to voice their concerns and be part of the conversation. In smaller programs, this type of process might work even better than in larger programs. In larger programs, a survey may help start the conversation before meeting with faculty.

After programs have chosen the best term for their context, they need to offer definitions for outcomes on their online pages. Additionally, if a university decides to use multiple terms on their website, the program should revise the page/document to make it clear which terms are broad versus those that are narrow. Because websites are open to anyone with an internet connection, such a practice allows all users of the page (teachers, students, parents, administrators) to understand what the program values and how that will transfer to teaching and learning.

Composition studies should also define outcomes terminologies in other places, such as professional development workshops. Like Gallagher argues, the perception of outcomes needs to change before the term itself really makes a difference. By giving faculty a definition of what the outcomes are, how they can be used, and how they relate to daily teaching practice, those in charge of programs are facilitating an environment where teachers use outcomes to inform their work. Doing so also allows programs to start changing the perception of outcomes from confusing, neoliberal documents to something that is actually useful to the program.

With clear definitions for outcomes language, programs are better equipped to make sure the outcomes are meeting their goals. By knowing which terms refer to broad goals and which refer to narrow ones, programs can evaluate which large and small goals the program wants and make sure those goals inform each other. They could even make a chart where they list the broad goals of the program and then work to create narrower goals for individual courses or degrees.

Defining Outcomes Language for Teachers

Once a program has chosen and defined its outcomes terminology and shared those definitions with teachers throughout the program, teachers are now better prepared to use the outcomes in their course design. I would like to demonstrate one way teachers might use these definitions to help them in their teaching practices. Those in charge of a writing program may want to run a training for their teachers to demonstrate how to do this process or create materials they can give to their faculty, or teachers can individually build on what I present here.

To help teachers know how to use outcomes definitions in teaching practice, I recommend using a chart with clear definitions of terms that move from broad to specific. For example, Ascough recommends using a chart with clear definitions for outcomes, outputs (which he defines as what teachers will do), and objectives (which he defines as what students will do), where the instructor can see how specific objectives relate to the larger outcomes of the program. Using these definitions, the instructor can follow backward design principles and ensure course materials are meeting the larger goals of the program.

To demonstrate how teachers might use Ascough’s chart to build a course, I will use the goals from a university’s webpage. I have kept this university anonymous as this is not meant to be a critique of their work and because the university has, since doing my study, updated their goals on the university website. The purpose in using this material is to show one way a program could think about revising their outcomes language practices and demonstrate how adding definitions and hierarchies of terms can add clarity for instructors building a course. In this case, the website identified four main goals at the top of the page for all writing programs classes; later, the website had a section called goals and objectives that occurred below each course title. Because the webpage first had four main goals listed and then a section with goals and objectives below each class, it seemed like the goals and objectives should be narrower. However, because they both had goals in the title, instructors may have thought the goals and objectives had the same broadness as the goals mentioned earlier and may not have known how to use each section for designing the courses.

Using Ascough’s model, the website could first define the terms it used. Based on how the webpage was already functioning, I recommend using goals for the writing programs classes and defining it the most broadly. I would then use the term outcomes for the specific courses to indicate these are still broad level concerns but slightly narrower than the earlier goals. (Universities and teachers could use different terms here; the most important part is that the terms are defined for the reader.) Then, in a chart, the instructor could use the goals and outcomes to help determine narrow lesson objectives, thus facilitating backward course design. An example of the chart can be seen in Appendix B, where I have used language from the university’s webpage, added definitions, and left the objectives section open for instructors to fill out. I have also included a sample of a chart in Appendix C that includes outputs to show two potential ways instructors could use this information. As the chart demonstrates, with clear definitions, programs can offer teachers documents that allow them to use outcomes in their day-to-day teaching practices instead of ignoring outcomes because they don’t know how to use them.

Defining Outcomes Language for Students

Students should also know the definitions for outcomes terminologies in the classes they take. While definitions on webpages are helpful in meeting this goal, defining outcomes language on syllabi also allows students to better understand what they will do in the course. Ascough argues that instructors should define outcomes terminology for students on syllabi and that doing so helps students better engage with the outcomes (broad goals) listed on the syllabus and theobjectives (narrow goals) taught in class. Defining outcomes on a syllabus could also be one way of helping students know the “general” and “specific objectives” of a course (Thompson 11) and see how their daily learning is leading them to accomplish a broader learning goal. WPAs can provide examples of what this would look like on a syllabus for teachers to use.

Programs might also facilitate student engagement with outcomes by creating additional materials that define outcomes terms and explain what outcomes are for students. For example, my institution recently created custom materials for the first-year writing textbook. The first section of these materials explains the first-year writing outcomes to students and helps students understand what they mean, why they are useful, and how students will accomplish these outcomes as they take the first-year writing course. Documents like this can be another powerful way to get students involved in their learning, which can happen when students understand what outcomes are.

Final Thoughts

Doing this definitional work with outcomes in composition studies allows us to take better control over the language that defines our work. Outcomes can be more than neoliberal hoops, but only if WPAs and faculty who work on outcomes define them in ways that make them usable. Defining the terms we use for outcomes and articulating those definitions on webpages, syllabi, departmental resources, etc. encourages those in composition studies to actually know what to do with outcomes statements in teaching and learning practices. As programs continue to define the terms we use and explain those terms to those who read and engage with them, we put ourselves in a position to take back outcomes for what they were originally created to do: help teachers be better teachers and students be better learners.

Appendices

Appendix A: Example of How to Define Outcomes and Objectives from University 4

Course Outcomes

By the end of the course, students will:

Demonstrate rhetorical awareness of diverse audiences, situations, and contexts.

Compose a variety of texts in a range of forms, equaling at least 7,500-11,500 words of polished writing (or 15,000-22,000 words, including drafts).

Critically think about writing and rhetoric through reading, analysis, and reflection.

Provide constructive feedback to others and incorporate feedback into their writing.

Perform research and evaluate sources to support claims.

Engage multiple digital technologies to compose for different purposes.

Detailed Learning Objectives

1. Demonstrate rhetorical awareness of diverse audiences, situations, and contexts.

This may include learning to:

Employ purposeful shifts in voice, tone, design, medium, and/or structure to respond to rhetorical situations

Identify and implement key rhetorical concepts (e.g.)., purpose, audience, constraints, contexts/settings, logos, ethos, pathos, kairos)

Understand the concept of rhetorical situation and how shifting contexts affect expression and persuasion

Understand how cultural factors affect both production and reception of ideas

Match the capacities of different environments (e.g.., print and digital) to varying rhetorical situations

2. Compose a variety of texts in a range of forms, equaling at least 7,500-11,500 words of polished writing (or 15,000-22,000 words, including drafts).

This may include learning to:

Adapt composing processes for a variety of tasks, times, media, and purposes.

Understand how conventions shape and are shaped by composing practices and purposes

Use invention strategies to discover, develop, and design ideas for writing

Apply methods of organization, arrangement, and structure to meet audience expectations and facilitate understanding

Apply coherent structures, effective styles, and grammatical and mechanical correctness to establish credibility and authority

3. Critically think about writing and rhetoric through reading, analysis, and reflection.

This may include learning to:

Read a diverse range of texts, attending especially to relationships between assertion and evidence, to patterns of organization, to the interplay between verbal and nonverbal elements, and to how these features function for different audiences and situations

Analyze, synthesize, interpret, and evaluate ideas, information, situations, and texts

Reflect on one’s composing processes and rhetorical choices

4. Provide constructive feedback to others and incorporate feedback into their writing.

This may include learning to:

Effectively evaluate others’ writing and provide useful commentary and suggestions for revision where appropriate

Use comments as a heuristic for revision

Produce multiple drafts or versions of a composition to increase rhetorical effectiveness

Learn and apply collaborative skills in classroom and conference settings

5. Perform research and evaluate sources to support claims.

This may include learning to:

Enact rhetorical strategies (such as interpretation, synthesis, response, critique, and design/redesign) to compose in ways that integrate the writer’s ideas with those from appropriate sources

Locate and evaluate (for credibility, sufficiency, accuracy, timeliness, bias and so on) secondary research materials, including journal articles and essays, books, scholarly and professionally established and maintained databases or archives, and informal electronic networks and Internet sources

Practice primary research methods (such as interviews, observations, surveys, focus groups, et cetera) and demonstrate awareness of ethical concerns in conducting research

Successfully and consistently apply citation conventions for primary and secondary sources

Explore the concepts of intellectual property (such as fair use and copyright) that motivate documentation conventions

6. Engage multiple digital technologies to compose for different purposes.

This may include learning to:

Understand writing as a technology that restructures thought

Use commonplace software to create media that effectively make or support arguments

Compose effective arguments that integrate words, visuals, and digital media

Evaluate format and design features of different kinds of texts

Demonstrate rhetorical awareness of how technologies shape composing processes and outcomes

Remediate writing from one form into another with a different rhetorical context

Navigate the dynamics of delivery and publishing in digital spaces

Appendix B: Example Chart for Programs

Writing Programs Broad Goals |

English 101 Outcomes—Broad concepts students will learn in English 101 |

English 101 Objectives—What students and teachers will do in class to meet the goals and outcomes |

|---|---|---|

Goal 1: Rhetorical Awareness Learn strategies for analyzing texts’ audiences, purposes, and contexts as a means of developing facility in reading and writing. |

Identify the purposes of, intended audiences for, and arguments in a text, as situated within particular cultural, economic, and political contexts. Analyze how genres shape reading and composing practices. |

|

Goal 2: Critical Thinking and Composing Use reading and writing for purposes of critical thinking, research, problem solving, action, and participation in conversations within and across different communities. |

Incorporate evidence, such as through summaries, paraphrases, quotations, and visuals. Support ideas or positions with compelling discussion of evidence from multiple sources. |

|

Goal 3: Conventions Understand conventions as related to purpose, audience, and genre, including such areas as mechanics, usage, citation practices, as well as structure, style, graphics, and design. |

Follow appropriate conventions for grammar, punctuation, and spelling, through practice in composing and revising. Apply citation conventions systematically in their own work. |

|

Goal 4: Reflection and Revision Understand composing processes as flexible and collaborative, drawing upon multiple strategies and informed by reflection. |

Produce multiple revisions on global and local levels. Suggest useful global and local revisions to other writers. Evaluate and act on peer and instructor feedback to revise their texts. Reflect on their progress as academic writers. |

|

Appendix C: Example Chart for Programs with the term Outputs

Writing Programs Broad Goals |

English 101 Outcomes—Broad concepts students will learn in English 101 |

English 101 Outputs—What students will do in the course |

English 101 Objectives—What the instructor will do to facilitate student doing and learning |

|---|---|---|---|

Goal 1: Rhetorical Awareness Learn strategies for analyzing texts’ audiences, purposes, and contexts as a means of developing facility in reading and writing. |

Identify the purposes of, intended audiences for, and arguments in a text, as situated within particular cultural, economic, and political contexts.

Analyze how genres shape reading and composing practices. |

|

|

Goal 2: Critical Thinking and Composing Use reading and writing for purposes of critical thinking, research, problem solving, action, and participation in conversations within and across different communities. |

Incorporate evidence, such as through summaries, paraphrases, quotations, and visuals.

Support ideas or positions with compelling discussion of evidence from multiple sources. |

|

|

Goal 3: Conventions Understand conventions as related to purpose, audience, and genre, including such areas as mechanics, usage, citation practices, as well as structure, style, graphics, and design. |

Follow appropriate conventions for grammar, punctuation, and spelling, through practice in composing and revising.

Apply citation conventions systematically in their own work. |

|

|

Goal 4: Reflection and Revision Understand composing processes as flexible and collaborative, drawing upon multiple strategies and informed by reflection. |

Produce multiple revisions on global and local levels.

Suggest useful global and local revisions to other writers.

Evaluate and act on peer and instructor feedback to revise their texts.

Reflect on their progress as academic writers. |

|

|

Works Cited

Allais, Stephanie. Claims vs. Practicalities: Lessons about Using Learning Outcomes. Journal of Education and Work, vol. 25, no. 3, 2012, pp. 331–354.

Allan, Joanna. Learning Outcomes in Higher Education. Studies in Higher Education, vol. 21, no. 1, 1996, pp. 93–108.

Anderson, Lorin W., and David Krathwohl (Eds.). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York, Longman, 2001.

Ascough, Richard S. Learning (About) Outcomes: How the Focus on Assessment Can Help Overall Course Design. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, vol. 41, no. 2, 2011, pp. 44–61.

Cohen, Louis, and Lawrence Manion. A Guide to Teaching Practice. Routledge, 1977.

Council of Writing Program Administrators [with responses by Keith Rhodes; Mark Wiley; Kathleen Blake Yancey]. The WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition. WPA:Writing Program Administration, vol. 23, nos. 1–2, 1999, pp. 59–66.

Ferris, Dana R., and John S. Hedgcock. Teaching L2 Composition: Purpose, Process, and Practice. Taylor & Francis Group, 2013.

First-Year Composition. Clemson University Department of English. https://www.clemson.edu/cah/academics/english/undergraduate/first-year-composition.html.

Gallagher, Chris W. The Trouble with Outcomes: Pragmatic Inquiry and Educational Aims. College English, vol. 75, no. 1, 2012, pp. 42–60.

Harden, Ronald M. Learning Outcomes and Instructional Objectives: Is There a Difference? Medical Teacher, vol. 24, no. 2, 2002, pp. 151–155.

Harrington, Susanmarie, Rita Malencyzk, Irv Peckham, Keith Rhodes, and Kathleen Blake Yancey. WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition. College English, vol. 63, no. 3, 2001, pp. 321–325.

Hartel, Richard W., and E. Allen Foegeding. Learning: Objectives, Competencies, or Outcomes. Journal of Food Science Education, vol. 3, 2004, pp. 69–70.

Huckin, Thomas. Content Analysis: What Texts Talk About. What Writing Does and How It Does It: An Introduction to Analyzing Texts and Textual Practices, edited by Charles Bazerman and Paul Prior, Routledge, 2003, pp. 19–38.

Hussey, Trevor, and Patrick Smith. Learning Outcomes: A Conceptual Analysis. Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 13, no. 1, 2008, pp. 107–115.

———. The Trouble with Learning Outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, vol. 3, no. 3, 2002, pp. 220–233.

———. The Uses of Learning Outcomes. Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 8, no. 3, 2003, pp. 357–368.

Kuh, George D., and Peter T. Ewell. The State of Learning Outcomes Assessment in the United States. Higher Education Management and Policy, vol. 22, no. 1, 2010, pp. 9–28.

Lauer, Claire. Contending with Terms: ‘Multimodal’ and ‘Multimedia’ in the Academic and Public Spheres. Computers and Composition, vol. 26, 2009, pp. 225–239.

Liu, Ou Lydia. Outcomes Assessment in Higher Education: Challenges and Future Research in the Context of Voluntary System Accountability. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, vol. 30, no. 3, 2011, pp. 2–9.

Maki, Peggy L. Assessing for Learning: Building a Sustainable Commitment Across the Institution. American Association for Higher Education, 2004.

Mager, Robert F. Preparing Instructional Objectives. Fearon, 1962.

Matsuda, Paul Kei. It’s the Wild West Out There: A New Linguistic Frontier in U.S. College Composition. Literacy as Translingual Practice: Between Communities and Classrooms, edited by A. Suresh Canagarajah, Routledge, 2013, pp. 128–138.

Outcomes. Purdue University College of Liberal Arts Department of English. https://cla.purdue.edu/academic/english/icap/courses/outcomes.html.

Powell, John W. "Outcomes Assessment: Conceptual and Other Problems." AAUP Journal of Academic Freedom, vol. 2, no. 2, 2011, pp. 1–25.

Prideaux, David. The Emperor’s New Clothes: From Objectives to Outcomes. Medical Education, vol. 34, 2000, pp. 168–169.

Rowntree, Derek. Educational Technology in Curriculum Development. Harper & Row, 1982.

Seal, Andrew. "How the University Became Neoliberal." The Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 64, no. 39, 2018.

Shavelson, Richard J. A Brief History of Student Learning Assessment: How We Got Where We Are and a Proposal for Where to Go Next. Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2007.

Thompson, Merle. Let’s Be Human About Behavior. Freshman English News, vol. 1, no. 2, 1972, p. 11.

Tyler, Ralph W. Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction. University of Chicago Press, 1949.

W131: Reading, Writing, and Inquiry. IUPUI School of Arts Department of English. https://liberalarts.iupui.edu/english/pages/writing-program-folder/courses.php.

Willard-Traub, Margaret K. Writing Programs and a New Ethos for Globalization. The Internationalization of US Writing Programs, edited by Shirley K Rose and Irwin Weiser, Utah State UP, 2018, pp. 44–59.

WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 38, no. 1, 2014, pp. 144–148.

Terminology Matters from Composition Forum 53 (Spring 2024)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/53/terminology-matters.php

© Copyright 2024 Alyssa Devey.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 53 table of contents.