Composition Forum 52, Fall 2023

http://compositionforum.com/issue/52/

Investigating Perspectives: The Impact of a Custom Common Textbook on FYW Instructors

Abstract: Researchers have examined many strategies for instructor preparation, but the role of common textbooks has received little attention, despite Yancey listing them as an essential feature to consider in developing instructor preparation. This case study examines the impact of the custom common textbook on graduate and professional instructors in a First Year Writing program at a large Midwestern research university. Data were collected through a survey, focus groups, and interviews with instructors, as well as interviews with textbook authors. I found that although instructors varied widely in their use of the text, it did contribute to instructor preparation by influencing choices of content and awareness of program culture and values, especially for experienced instructors. Although additional instructional preparation measures are necessary for new instructors, common textbooks should not be ignored in research and assessment of instructor preparation strategies.

1. Introduction

A perennial question for writing program administrators (WPAs) is how to prepare the graduate and professional instructors who teach the majority of composition courses at many institutions in the United States (Lynch-Biniek). Instructors at any institution vary widely in their teaching experience and pedagogical knowledge. Many have never taught, or even taken, a composition course (Wardle and Scott) and lack pedagogical and disciplinary knowledge (Bleich; Lynch-Biniek). Others have taught first-year writing at other institutions, or taught courses other than composition, but are unfamiliar with their current institution’s local context and approach to composition. These circumstances mean that first-year writing (FYW) programs must prepare new instructors to be effective in the classroom, as highlighted by the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s CCCC Statement on Preparing Teachers of College Writing. And WPAs have a parallel responsibility to assess the effectiveness of enacted instructor preparation practices, as noted by scholars including Taggart and Lowry and Cicchino.

The case study presented here considers one instructor preparation strategy by examining the impact of the custom common textbook Perspectives[1] on instructors in a first-year writing (FYW) program at a large Midwestern research university. Through a survey, interviews, and focus groups with instructors, and interviews of former program administrators who authored the textbook, I documented instructors’ use of Perspectives and its contributions to instructor preparation. My findings suggest that a custom common textbook can contribute to instructor preparation by helping establish program expectations, but other instructor preparation must be carefully calibrated to engage productively with the text in order to maximize its benefits. This case reveals important takeaways for WPAs regarding the role of common textbooks in instructor preparation, benefits and drawbacks of locally authored texts, and the importance of assessment.

1.1 Approaches to New Instructor Preparation

The scholarship exploring instructor preparation practices primarily focuses on training practices for new graduate instructors (Taggart and Lowry; Pytlik and Liggett, p. xiii). For example, Pytlik and Liggett’s seminal book on instructor preparation contains theoretical articles and empirical studies of widely-discussed instructor preparation strategies including pre-semester workshops, practica, and mentorship. Latterell’s 1996 survey documented a variety of graduate instructor preparation strategies used in rhetoric and composition programs, including fall orientations for new graduate instructors and practica focused on day-to-day teaching concerns. Cicchino’s 2020 follow-up work similarly identified frequent use of orientations and practica and highlighted a need for additional theory-based pedagogy education and increased resources for instructor preparation.

In contrast, the role common textbooks play in instructor preparation has received little scholarly attention. This is despite the fact that common textbooks—which I define as texts selected by program administrators for use in all sections of a course—are frequently used in FYW programs. Although textbooks are primarily aimed at student audiences, these texts also have important impacts on instructors, both recommending and constraining possibilities instructors consider in developing their courses. Lynch-Biniek notes that new contingent faculty—many lacking rhetoric or writing studies backgrounds—often draw their content and approach entirely from textbooks, especially those recommended or mandated by WPAs. And Taggart and Lowry note that new graduate instructors, eager for practical resources for managing the day-to-day activities of a composition class, are likely to lean on textbooks for support. Common textbooks adopted for an entire program can also support curricular consistency.

For this reason, the FYW textbook is one of the twelve characteristics Yancey includes in her “heuristic for designing and reviewing TA development programs” (65). She argues that “the role of the textbook needs to be included and possibly foregrounded” in assessing TA development programs because of its profound impact on instructors (Yancey 70). My study takes up this charge by documenting the impact of a common textbook on instructors at one institution.

1.2 What’s in a Textbook?

Past studies of textbook use in new instructor preparation have largely been critical. Several scholars position common textbooks as the under-resourced or lazy WPA’s alternative to new instructor preparation. As early as 1952, Allen noted that simply giving new instructors a textbook, with no additional training provided, was a common but ineffective instructor preparation strategy. Bleich argues that textbooks enable new composition instructors to “seem to be teaching writing” despite lacking pedagogical awareness and disciplinary knowledge (18). In a similar vein, Powell et al., discussing their TA preparation practices, write, “It is because of the extensive theoretical and practical training offered in the [TA preparation] course that program administrators feel comfortable in allowing even inexperienced teachers to design curricula and choose texts” (101). In contrast, Powell et al. seem to suggest, mandating a common textbook is the unfortunate—if necessary—choice of programs that lack the resources or willingness to pursue more robust preparation strategies. Notably, however, these critiques seem to treat textbooks as a standalone instructor preparation strategy rather than considering how they might function as one element in a broader array of instructor preparation tools. This study considers an alternative model wherein a textbook functions as one piece of a multi-pronged approach to instructor preparation, an approach used in many FYW programs.

Some of the hesitancy about textbooks is likely grounded in the long-standing theoretical critiques of textbooks. Earlier critics problematized the role of traditional single-authored textbooks in the classroom, arguing they falsely suggest to students that there is a single correct approach to writing and fail to capture current knowledge in composition theory (e.g., Gale and Gale; Welch). More recently, Burrows has critiqued representations of Black writers in composition anthologies, and Russell has argued that popular textbooks perpetuate problematic conceptions of language that are inconsistent with equity goals. Certainly, these important critiques should not be ignored in discussions about the role common texts play in FYW programs.

However, even as this debate plays out theoretically, textbooks continue to be an integral part of many FYW programs; thus, it is important to document their effects. Further, custom textbooks are quickly growing in popularity (Fountainhead Press); since they are written by WPAs for a local audience and are easily revised, they may differ in intent and impact from traditional textbooks, for example by better reflecting current disciplinary knowledge, taking a less prescriptive approach, or providing useful local insights that traditional textbooks do not. This study examines the effects of one custom common textbook to assess their benefits and limitations in instructor preparation.

2. Methods

This case study examines the impact of a custom common textbook on instructors in the FYW program at a large Midwestern research university in 2019. The program allows all instructors to design their own syllabi and assignments, but has shared learning objectives and developed a short custom textbook, Perspectives, that is required for all sections of the course. I examined how Perspectives impacts FYW instructors by studying these questions:

How do new instructors use Perspectives and the material from Perspectives in their courses?

How does Perspectivesimpact instructors’ understanding of FYW program culture and FYW pedagogy?

2.1 Case Study

The FYW program studied here is large; in 2018-2019, it served 3,200 students in 142 sections of a single-semester FYW course. The program, housed in a Writing Studies department, states that its practices are “informed by the latest research in Writing Studies about what writing is and how best to teach it” (Perspectives). At the time of this study, which was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, almost all sections of FYW were offered face-to-face, meeting in person for four hours per week. Enrollment was capped at twenty-four students per section.

The program employs a mix of professional instructors, who work full-time on renewable one- or three-year contracts, and graduate instructors from five programs: Writing Studies MA and PhD, English MFA and PhD, and American Studies PhD programs. Professional instructors have diverse backgrounds ranging from degrees in rhetoric to English literature to creative writing. Graduate instructors generally teach in the program for one to three years, while professional instructors have in some cases taught for multiple decades. (See section 2.2.4 for more information on program demographics.)

Overall, this program’s instructors represent a unique population in the instructor preparation literature, which almost exclusively focuses on graduate instructors in English programs. This case study also provides unique insights because many instructors in the program have taught FYW at this institution previously; I refer to these instructors as “experienced instructors” throughout the text. And even some instructors I classify as “new instructors”—those in their first year of teaching FYW at this institution—had taught FYW at other institutions and/or taught other classes at this institution prior to teaching FYW. These instructors’ needs in and responses to instructor preparation are different from those of the typical first-year graduate instructor teaching for the first time, but are under-examined in the current literature.

2.1.1 Textbook

Perspectives is a short first-year writing textbook authored locally by a director and assistant director of FYW, a graduate assistant in FYW, and a librarian. Authors I interviewed for this study (see 2.2.3 for methods) explained that the content of Perspectives was developed collaboratively with instructors in the program, who were given multiple opportunities to suggest topics and offer feedback. Perspectives replaced a style manual that had previously served as a common text for the course, and was meant to better instantiate the program’s rhetorical, process-based approach. At the time of this study, the text was in its third annual edition.

Although it captures the program’s core values, Perspectives was also intended to fit seamlessly into a variety of FYW course designs to allow instructors autonomy to, as one administrator put it, “invent… a good version of the class for themselves and their students.” As a result, the authors chose to keep Perspectives quite brief, focusing only on the most essential elements of the course. Parts I, II, and III review key course content, including process, rhetoric, and research:

Part I describes the program’s approach to writing instruction, emphasizing that there is no “One Right Way” to write. This section also includes information about course outcomes and class processes like peer review, office hours, conferences, and class discussion. Part I is ten pages long.

Part II covers the writing process (including a recursive understanding of process; strategies for invention, drafting, and revision; and the role of peer and instructor feedback in revision) and rhetorical awareness (including the rhetorical situation; rhetorical appeals; claim/opinion/fact; logical fallacies; critical reading; and the Toulmin model). Part II is thirteen pages.

Part III provides information on the research process, including topic generation and refinement, summary and paraphrase, analyzing sources, and information about the institution’s library search tools and databases. Part III is also thirteen pages.

Each of these sections directly addresses students in an accessible tone. Quotes from previous FYW students at the institution, as well as from published authors, are interspersed to emphasize key points. A few short activities (e.g., “write a reverse outline,” “draw a mind map,” or “write down some search terms you might use”) are included. Overall, these sections of the text provide high-level overviews with the intention that instructors will supplement Perspectives with other readings, activities, and instruction.

Parts IV and V of Perspectives provide resources for citation and sample student essays, and are set up to allow instructors to pick and choose what elements they will incorporate.

Part IV provides documentation guides for MLA and APA citation styles, with examples. Part IV is twenty-five pages.

Part V contains eight samples of student writing in a variety of genres that have previously won FYW Program awards, with a brief introduction to each essay commenting on its strengths. Part V is sixty-five pages.

Perspectives was printed for the program by a custom textbook publisher and was available exclusively through the university bookstore in a paperback format. The cost was approximately $15 at the time of this study; authors considered multiple possible publishers and waived royalties to keep the cost low for students. Perspectives was automatically assigned as a required text for every section of the course. Instructors also independently selected additional texts to use with students, most often popular textbooks such as Everyone’s an Author (Lunsford et al.) or They Say/I Say (Graff and Birkenstein).

Notably, because it was developed locally, Perspectives is tailored specifically to the institution and the course. For example, Part I includes the course description and university policies; refers students to local resources such as library programs and the writing center; and describes the program’s approach to the course. Part III, on research, aligns in structure with a library workshop included in most sections of the course, promoting continuity across resources. Perspectives also includes quotes and samples of writing from students at the institution. In interviews, the authors explained that they valued a printed text as a “material” representation of the program for all stakeholders that captured a shared sense of the program’s core values.

Importantly, although its primary audience is students, Perspectives is also intended to assist in instructor preparation: its authors’ note states, “The purpose of [Perspectives] is to introduce instructors and students to the culture of writing and research at the [institution], highlight expectations, and provide resources for writing throughout the course and semester. [Perspectives] was created to facilitate a shared, common experience and approach to the teaching, learning, and practice of writing within the FYW Program” (emphasis added). Similarly, authors I interviewed told me that Perspectives spoke to a dual audience of students and instructors, with the goal of “orient[ing] instructors that are not in our department [Writing Studies] to our approach to writing, that there’s no ‘One Right Way’ and that it is a conversation.”

There are many examples throughout Perspectives of language that speaks to both students and instructors. For example, Part I states:

In a ‘monological’ approach, Writing with a capital ‘W’ is imagined to be one thing in all times and places, and everyone in the classroom is expected to write, and be, pretty much the same. Research has demonstrated that such approaches don’t reflect the truth about writing, and they don’t help students grow as writers. Instead, our program embraces a ‘dialogical’ approach.

Language like this is intended to orient both new instructors and students to the course. Perspectives also lists specific pedagogical practices students will experience in the course, including rhetorical reading, class discussion, conferences, and feedback on writing. In so doing, Perspectives is meant to promote baseline continuity in pedagogical practices across sections of the course without being strongly prescriptive.

2.1.2 Additional Instructor Preparation

In addition to reading Perspectives, all graduate instructors attend a day of shared orientation each year, which includes a session brainstorming strategies for using Perspectives in one’s course. Throughout the year, both graduate and professional instructors are asked to attend monthly professional development sessions, though attendance varies. These sessions aim to keep instructors throughout the program engaged in pedagogical education and build teaching community, as advocated by Latterell.

Additional support is provided for new instructors. New instructors participate in a one-week orientation prior to the semester and receive one-on-one feedback on their syllabus and course planning from program administrators. New instructors are also grouped into teaching groups of four to five instructors who meet monthly with an experienced instructor, called a teaching group leader, to discuss progress and brainstorm solutions to challenges. Orientation and teaching groups provide new instructors with targeted support that supplements program-wide trainings.

Notably, though some instructors in the program have taken pedagogy courses in Writing Studies or at other institutions, the program does not require a practicum or pedagogy course because of curricular and resource constraints. In the absence of such a course, Perspectives is one of the strongest articulations of the program’s expectations.

2.2 Data Collection

I used multiple methods to collect data: a survey of instructors including both quantitative and qualitative questions, interviews and focus groups with instructors, and interviews with Perspectives authors. The institution’s IRB determined the study was exempt from review.

2.2.1 Survey of Instructors

I distributed a survey in Qualtrics to FYW instructors in spring 2019. The survey was sent via email to all forty-five instructors; they also received reminder emails two and three weeks later. Ultimately, fifteen instructors participated in the survey, representing a response rate of 33%.

The survey included a mix of open- and close-ended questions (see Appendix A). Open-ended questions asked participants about their initial and current perceptions about Perspectives; how reading Perspectives affected their perceptions of a FYW course; and how and why they decided to integrate Perspectives and/or material from Perspectives in their courses. Supplemental close-ended questions helped generate more directly comparable answers; for example, asking instructors “which section(s) of [Perspectives] did you assign your students to read?” with a checkbox list of sections of Perspectives helped me quickly compare new instructors and ensured a full picture of their use of the text. I also included close-ended questions about basic demographic information like program affiliation and length of time instructors had been teaching.[2]

2.2.2 Focus Groups and Interviews with Instructors

To generate more in-depth qualitative data, I also conducted in-person focus groups and interviews with instructors. I conducted three focus groups of three to five participants, for a total of fourteen instructors. Focus groups took place during regular meetings of teaching groups. I conducted interviews with seven instructors. Some interview participants volunteered to be interviewed after completing the survey; the rest were recruited through direct outreach or snowball sampling. Both focus groups and interviews were semi-structured, beginning with standard questions (Appendix B) and following up for clarification and to elaborate on emerging themes.

2.2.3 Interviews of Authors

I conducted in-person interviews with three of the authors of Perspectives, all of whom had served in leadership roles in the program. I used a semi-structured format in interviews (see Appendix C for initial questions). Interviewing the authors allowed me to gain greater insights into the potential, both realized and unrealized, of Perspectives, and into the tensions and miscommunications among program constituencies that emerged in my interviews.

2.2.4 Participant Demographics

My study included instructors from all program constituencies. Table 1 displays participation by affiliation.

Table 1. Participation by Method and Affiliation.

Profes- |

Writing Studies MA & PhD |

English Lit PhD |

English MFA |

American Studies PhD |

Graduate Instructor, Affiliation Unstated |

Author/ |

TOTAL |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Interviews |

2 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

10 |

Focus Groups |

1 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

N/A |

14 |

Survey |

3 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

N/A |

15 |

TOTAL[3] |

4 (12.5%) |

6 (18.8%)[4] | 13 (40.6%) | 6 (18.8%) | 2 (6.3%) | 1 (3.1%) | 3 |

35 |

Total in Program |

12 (27.9%) |

4 (8.9%)[4] | 17 (37.7%) | 10 (22.2%) | 3 (6.7%) |

My study also included both new and experienced instructors. Table 2 displays the participant breakdown by semesters of FYW teaching experience at the institution for each method.

Table 2. Instructor Participation by FYW Experience

New FYW Instructor (<1 year teaching FYW at this institution) | Experienced FYW Instructor (≥1 year teaching FYW at this institution) | Did Not Respond to Question | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Interviews |

0 |

7 |

N/A |

7 |

Focus Groups |

11 |

3 |

N/A |

14 |

Survey |

6 |

8 |

1 |

15 |

TOTAL[5] |

16 (50.0%) |

15 (46.9%) |

1 |

32 |

Total in Program |

18 (40.0%) |

27 (60.0%) |

2.3 Data Analysis

I calculated descriptive statistics to provide a quick quantitative snapshot of the demographics and opinions of my participants.

I coded qualitative survey responses and interview and focus group transcripts using a two-phase coding process derived from Saldaña, first identifying broad themes in participant statements, then refining my initial coding scheme in a second pass. My coding scheme ultimately included eleven broad coding categories:

Autonomy/choice/restriction

Descriptions of Perspectives

Development of Perspectives

Ideal common text

Impact of Perspectives on instructors

Instructor feedback on how Perspectives works for students

Program culture and hierarchy, including tensions

Program intentions, expectations, and communication about Perspectives

Role in course

Student feedback on Perspectives

Support structures around Perspectives

These coding categories were primarily descriptive, documenting topics of discussion and common themes in participant responses, but my subcodes also included concept codes that “extract[ed] and label[ed] ‘big picture’ ideas suggested by the data” (Saldaña 97). My full coding scheme is reflected in Appendix D.

I employed “drag and drop” coding in Nvivo, manually selecting text to which a particular code applied rather than using a preset unit of analysis. I employed simultaneous coding, often assigning multiple coding categories to the same passage.

To support the validity of my coding scheme, I conducted an inter-rater reliability test with a researcher not connected to the study. To conduct this test, I segmented one interview into semantic “lumps” — short snippets of one to three sentences that expressed a single concept or idea (Saldaña 23). I provided my rater with a guide to my codes, and we both coded each semantic unit using that scheme. We achieved 80% agreement in our coding, one indication that my coding scheme is valid.

2.4 Positionality

I held a graduate research position while completing this project. My status as a young female graduate student and preexisting relationships with many graduate instructors in the program generally made participants, especially graduate instructors, feel comfortable sharing their thoughts with me.

Although I did not have a formal teaching or administrative role in the program being studied, at the time of the project, I was helping to edit the next edition of Perspectives. This role gave me a more in-depth understanding of the program and textbook, which helped me formulate my study questions and attend to potential themes. However, some participants seemed to be more reticent to criticize Perspectives because I held this role. To help ameliorate concerns, I stressed to participants that I would maintain confidentiality and was eager to hear any thoughts they had, whether positive or negative.

3. Results

3.1 Use of Perspectives

Although all instructors are required to use Perspectives in some capacity in their courses, they have autonomy over how they use it. Thus, my survey, interviews, and focus groups began by asking instructors how they used Perspectives in their courses.

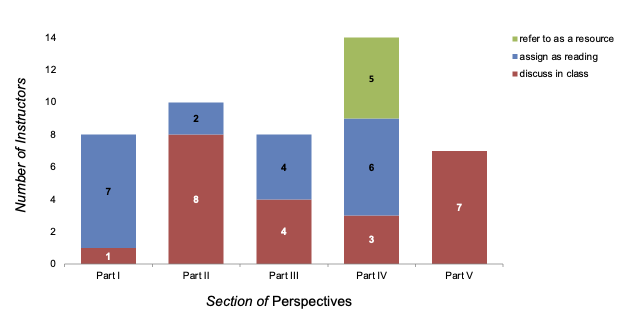

Figure 1 shows, for each section of Perspectives, the total number of survey respondents that reported discussing that section in class, assigning it as reading, and referring students to it as a resource. The results are presented additively since, by my definition, every instructor who discussed Perspectives in class also assigned it as reading, and every instructor who assigned a section as a reading also referred students to it as a resource. Thus, the height of each bar represents the total number of instructors who asked their students to engage with that section of Perspectives in some way.

Figure 1. Survey results: Reported use of Perspectives

by section (n=15)

Use of Perspectives varied significantly by section. Part IV, which discusses citation, was at least referenced by most instructors. Otherwise, the most popular section of Perspectives, and the one instructors were most likely to discuss in class with their students, was Part II, which covers the writing process and rhetoric. The section instructors were least likely to discuss with their students was Part I, which discusses the program’s approach to the FYW course.

Qualitative responses in the survey, interviews, and focus groups demonstrated that instructors took a wide variety of approaches to incorporating Perspectives in their courses. Some used entire sections of Perspectives as broad introductions to a unit, assigning all of Parts I, II, and/or III early on in a unit or the course. These instructors noted that Perspectives functioned as a broad, general resource to introduce concepts. One explained, “I have them read [Perspectives] knowing that… we’re gonna come back and revisit this at length.” Others used Perspectives in a more piecemeal way, having students read the paragraphs focused on a single topic as they fit into the overall course. Almost all instructors also used other readings to supplement Perspectives.

Consistent with their structure, Parts IV and V were typically used in a piecemeal way. Instructors often referenced Part IV, on citation, in class, and some used it as an in-class example to reference when practicing these skills. But most of these instructors noted that they preferred and also utilized other resources such as Purdue OWL citation guides that they felt more thoroughly and clearly covered the same material. Instructors engaged more substantively in class with Part V, which includes sample student essays, with many noting that they used one or two sample essays to explain assignments and practice peer review.

Every participant used Perspectives as one of multiple resources, supplementing with other readings and in-class instruction. The vast majority of instructors used at least one other textbook. This was consistent with the authors’ intentions; Perspectives was always meant to provide a brief introduction and be supplemented by other texts.

For some instructors, Perspectives worked well as a core text supplemented with additional readings: one said, “there are very few things in [Perspectives] that are new to all of my students, but it is very helpful for filling in some gaps so that the whole class can have more or less the same grounding in the basics.” But for other instructors, the need to supplement Perspectives made its value less clear. Most instructors preferred the texts they chose themselves, which typically covered most of what they valued in Perspectives in more depth and provided additional material. For example, one said, “Working with Everyone’s an Author this year, I really like having the heftier textbook…. Whereas [Perspectives has just one page] on quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing, [Everyone’s an Author] has fifteen, and it’s got more examples.” Instructors also frequently noted that the brevity of Perspectives limited its usefulness. This included both very general critiques—several said students found it too “obvious” or basic—to quite specific complaints—several noted that the MLA section was missing citation information for commonly used sources like Twitter posts.

Although authors worked to keep the cost of Perspectives low, questions about its cost and value arose throughout survey, interview, and focus group results. Several instructors noted that they felt they needed to find ways to use Perspectives to justify students’ purchase, saying, for example, “I basically feel like I have to use it regularly so that I don’t waste my students’ money” and “Although I’d prefer to use OWL/Purdue citation help instead of [Perspectives] … I have recently referred students to [Perspectives] to justify their requirement of paying for the resource. I wouldn’t assign the text at all if I wasn’t required to do so.” Many asked why Perspectives could not be offered freely online. Instructors also sometimes faced student complaints that Perspectives was an unnecessary cost; one instructor read me comments from her student evaluations such as “Students should not be spending money on material that could easily just be discussed in class” and “I don’t think the [Perspectives] book was very useful because it didn’t have any new information.” Two instructors stated that they did not use Perspectives and told students to return it.

3.2 Perspectives as Instructor Preparation

In addition to serving as a course text, Perspectives was also designed to contribute to instructor preparation by introducing instructors to the pedagogy and content of the program’s FYW class. One author explained that, although instructors might vary in their use of Perspectives, it should “influence” both “the curriculum” and “approach.” Accordingly, in this section, I analyze how Perspectives influenced both curricular choices and pedagogical knowledge.

3.2.1. Influence on Curricular Choices

Even when instructors do not use every section of Perspectives, it is important to the program that they cover general concepts from the text, which are aligned with key learning outcomes. Generally, this seems to have happened: eight out of eleven survey respondents agreed or somewhat agreed that “Perspectives helped me know what content to include in my course.” This seems to have been a trend over time; authors reported that in the first year they used Perspectives, “we had GTAs [graduate teaching assistants] say ‘I didn’t teach any of this in my course last year [before I had Perspectives]. But I am now.’ And that was what we wanted… those foundational touchstones.”

Similarly, in interviews and focus groups, instructors widely reported finding Perspectives helpful as a ‘checklist’: “a list of ‘these are some of the things that could be good for me to cover’” or “a guideline of what I should be covering.” These insights were especially helpful for graduate instructors outside Writing Studies, who often reported feeling unsure what content belonged in a FYW course.

Survey results asking instructors which concepts from Perspectives they covered in their courses confirmed that almost all instructors covered all key concepts from Perspectives (though it is possible results are slightly skewed because several instructors who indicated they did not use Perspectives frequently did not complete this question). Table 3 lays out responses to this question, with a column summarizing results from Figure 1 documenting use of each section of Perspectives for comparison.

Table 3. Survey results: How instructors cover Perspectives content in class.

Course Concept |

Number of instructors who reported covering that concept, whether or not they used Perspectives to do so (n=13) |

Number of instructors who reported using the relevant section of Perspectives (see Figure 1; n=15) |

|---|---|---|

Introduction to the course

|

12 |

8 |

Process |

12 |

10 [6] |

Rhetorical situation |

13 |

10 [6] |

Research process |

13 |

8 |

MLA and/or APA documentation

|

12 |

14 [7] |

3.2.2 Influence on Pedagogy and Knowledge of Composition

In addition to outlining basic course content, Perspectives also aims to communicate the values and practices of institution’s FYW program and, by extension, some pedagogical information. Perspectives, especially Part I, instantiates the program’s approach to the course by describing the teaching practices and approach to writing that students will experience in the course. In the survey, I presented four statements about instructors’ perceptions of Perspectives and asked participants to indicate their level of agreement on a Likert scale. The results of these questions are reflected in Table 4.

Table 4. Survey results: Perceptions of Perspectives as instructor preparation (n=11).

Totally Agree |

Somewhat Agree |

Somewhat Disagree |

Totally Disagree |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Perspectives reflects my understanding of aims of FYW program |

2 |

9 |

||

Perspectives helped me understand FYW culture |

2 |

9 |

||

Perspectives helped me know what content to include in my course |

1 |

7 |

3 |

|

Perspectives gave me pedagogical insights |

4 |

6 |

1 |

As Table 4 demonstrates, most instructors agreed that Perspectives helped them understand the local culture and goals of the FYW program. Similar sentiments were expressed by some interview participants; for example, one stated, “the department seemed to take a lot of pride in not teaching grammar… and [Perspectives] seemed to get that, so I thought, okay, if I just read [Perspectives] I’ll be in line with the department ideology of teaching writing.”

In contrast, most instructors disagreed that Perspectives gave them insights about pedagogy more generally. One interviewee said, “You’re talking about [Perspectives] as a tool, teaching us to teach, which it is not. At all.” Another, similarly, said that compared to the practicum-based instructor preparation she experienced at another institution, Perspectives “was barely adequate. It doesn’t even come close.” An especially common complaint was a lack of guidance on day-to-day activities for the classroom. One instructor said that, for Perspectives to function well in instructor preparation, it would need an instructor-specific edition offering concrete suggestions: “In your class, try this.”

3.2.2.1 Local vs. Pedagogical Knowledge: A Hidden Curriculum

On their face, these findings are consistent with Cicchino’s finding that graduate instructor preparation is often heavily weighted towards “the development of local knowledge”—“local curriculum,” and university-specific policies and resources rather than primarily emphasizing pedagogy or disciplinary knowledge (98-99). This seems to be true in the FYW program I studied: instructors generally agreed that Perspectives helped them understand local curriculum but disagreed that it offered pedagogical insights. Even the authors identified the primary function of Perspectives in instructor preparation to be communicating local values and practices rather than more general pedagogical or theoretical lessons.

However, as Cicchino notes, it is difficult to draw clear distinctions between knowledge of a program’s policies and curriculum and more abstract pedagogical and theoretical awareness. Day-to-day practices are typically informed by composition pedagogy, which is in turn informed by disciplinary knowledge. Cicchino argues:

No discrete division should exist between theoretical knowledge, local curriculum and policies, and general teaching practices, and I imagine many WPAs would argue that their local curriculum is informed by compositional theory and scholarship in rhetoric and composition and education (98-99).

This is certainly true of the program studied here: an author’s note in Perspectives describes the program as “informed by the latest research in Writing Studies about what writing is and how best to teach it,” and Perspectives outlines local theoretical commitments (deemphasizing grammar, focus on rhetoric and a recursive writing process) and pedagogical practices (conferences, frequent feedback) that are commonly recognized as best practices.

Certainly, then, there is pedagogical knowledge represented at least indirectly in Perspectives. And in fact, instructors with greater knowledge of pedagogy were able to identify and learn from its pedagogical commitments. One said, “I was a writing consultant at a university before… so I have some of the language and some of the ideas behind [Perspectives]. But I feel like my teaching values were very much shaped by this department and the FYW program, and I think [Perspectives] is a big part of that.” Another instructor said their prior knowledge was essential to understanding the text: one graduate instructor said, “I feel like [Perspectives] explains an approach to composition that I understand because I’ve taken composition pedagogy. But if I hadn’t taken that class… I would not necessarily buy into it, if I was coming from a different discipline.” Notably, of the four survey participants who at least somewhat agreed that Perspectives offered pedagogical insights (see Table 4), three had taught in the program for at least five semesters.

Pedagogical lessons were less clear, however, to those without prior knowledge. This too is consistent with Cicchino’s arguments. She warns:

When local curriculum is presented to GTAs as policies or standards for local practice without exposing them to the theoretical underpinnings of said curriculum, GTAs are not reflecting on how their daily practices are linked to compositional theory nor are they recognizing that this approach to teaching writing is more theoretically sound than other approaches (e.g., a current-traditional or a literary approach to composition) (99).

This outcome seems to have occurred in the program I studied: while the practices mentioned in Perspectives were grounded in disciplinary knowledge, this was not necessarily clear to new instructors, and as such they felt Perspectives did not include pedagogical information. This may explain why instructors, despite almost universally stating that Perspectives aligned with their approach, still sometimes used approaches authors said were inconsistent with Perspectives, such as focusing exclusively on literary texts and analysis or strongly emphasizing grammar.

3.3 Context Matters: Other Instructor Preparation

Of course, no textbook exists in isolation, and other program support structures should also help instructors develop theoretically-informed approaches. Unfortunately, my findings suggest that, at least at the time of this study, other instructor preparation addressed instructors’ day-to-day concerns but fell short in helping them develop pedagogically and interact productively with Perspectives.

One issue that emerged was confusion about expectations for use of Perspectives. One typical instructor said, “The… basic instruction is that it would be required for all courses, but I don’t know if we ever really had a conversation—a really in-depth conversation—about how it was best employed or whether one should employ it, even.” Another said explicitly, “The department says it’s required.… And the communication that I’ve gotten from [administrator] was ‘You will use this. Period’”; ‘use’ was never defined. A few even had inaccurate beliefs, saying they thought “we didn’t need to use it.” Lack of clarity in program expectations might help explain why instructors’ use of Perspectives varied widely.

Additional guidance from the program might also help instructors use the text more productively. Although authors accepted that use of Perspectives would vary, data on use of the text revealed missed opportunities; for example, multiple authors were disappointed that Part I, which lays out the program’s approach to the course, was the least used section of the text. One said, “I think Part I… really helps the students realize that this class is more about their writing than some mythical standard. So I would think that it would be nice to actually just briefly recognize that in the classroom.” Another echoed this sentiment, saying that, while instructors might pick and choose among concepts in other sections of Perspectives, Part I was essential to a shared understanding of the course. Communicating information like this more clearly to instructors might have changed how they perceived and utilized Perspectives.

Some of these gaps in communication are likely attributable to changes in interactions between Perspectives and other instructor preparation that had occurred over time. When Perspectives was initially developed, the authors and teaching group leaders did significant work to introduce it in instructor preparation sessions. One author argued the “metanarrative” work of unpacking implicit values in Perspectives was crucial to its function in instructor preparation. This work likely contributed to experienced instructors’ positive perceptions of the text and its pedagogical functions. Unfortunately, in subsequent years, changes in staffing and a reduction in funding for teaching group leader training resulted in administrators and teaching group leaders being less familiar with Perspectives, and its role in instructor preparation sessions waned accordingly. This shift likely contributed to new instructors’ uncertainty about the meaning of Perspectives and its role in their courses.

4. Discussion

My findings touch on the value of the brevity, local grounding, and format of Perspectives. I discuss these themes in turn, then discuss what takeaways my findings offer WPAs.

4.1 Brevity

The brevity of Perspectives was an intentional choice, but one that was often critiqued by instructors. One more minor issue is that, for many instructors, its brevity limited its utility in the classroom. One instructor said “I think that for about half of my students, it’s not enough, and the other half of my students already know it”—in other words, students familiar with a concept found Perspectives “obvious,” but it lacked enough detail to introduce new concepts effectively to students who were not already familiar with them. This sentiment was echoed by many other instructors. It is worth further investigating, then, if or where detail could be added to Perspectives to make it a more effective classroom tool. However, if instructors supplement effectively, the text’s brevity is not hugely problematic, especially if Perspectives were made into a free online resource to help address cost concerns. More important and theoretically significant are the broader underlying questions about the ideal role of a common text in a course.

Generally, the program’s approach emphasizes instructor autonomy, and Perspectives is intentionally brief and general in order to fit into a variety of course designs. One author argued that this was important to maintaining substantial autonomy for instructors to adapt the course to their own expertise and student needs, saying:

I think [Perspectives is] an initial gesture that complicates a kind of grammar-oriented or correctness-oriented way of thinking about writing and the teaching of writing… My sense is that good teaching relies upon people inventing a good version of the class for themselves and their students.… Putting people in the position of having to do that difficult work of figuring out for themselves kind of how to conceive the class and build the activities that reflect that conception.

Consistent with the program’s goals, instructors generally did not find that Perspectives constrained their approach, both because the program did not mandate particular ways of using the text and because it was fairly general.

The program’s vision of engaging instructors in the intellectual work of developing their courses, rather than prescribing a single approach, seems to echo the goals for instructor preparation advocated by scholars like Latterell: that new graduate instructors understand “teaching as a vibrant, constantly evolving, and valued” intellectual practice (21). But my findings suggest that the effectiveness of the program’s approach was mixed and highly dependent on instructors’ prior experience and knowledge.

Experienced instructors with knowledge of pedagogy typically appreciated and enjoyed the autonomy they were afforded, which allowed them to adapt their courses to their teaching style and student needs. This population often appreciated Perspectives as a helpful local resource that connected them to important programmatic values regardless of their engagement with other professional development. These instructors were well-positioned to make informed decisions in using and supplementing Perspectives given their greater familiarity with composition pedagogy and other resources available; while they might have preferred a more detailed text in some cases, they did not suffer for its absence. The utility of briefer, local texts like Perspectives cannot be ignored given these benefits for experienced instructor populations.

In contrast, however, the level of autonomy and relatively light guidance provided by the program was problematic for new instructors without disciplinary knowledge, many of whom reported unease or uncertainty about whether they were meeting expectations. One instructor said, “I really remember that feeling of going into that first summer before I was going to start teaching first-year writing in the fall… I was so overwhelmed, and definitely was having choice paralysis, a lot of difficulty thinking about what actually should I cover, what does this program expect me to cover?” These instructors reported needing much more support than they received, with many wishing for a common syllabus or set of recommended readings. Without greater program support, many relied on other graduate instructors, longer textbooks, or syllabi and materials from other institutions for structure and guidance.

In many ways it is unsurprising that new instructors wished for more concrete resources; many studies have documented that new instructors are eager for practical guidance (Lynch-Biniek; Taggart and Lowry) and often initially disinterested in pedagogical theory (Cicchino). Perspectives authors hoped their non-prescriptive approach would push new instructors to engage more thoughtfully with pedagogy. This plan was not unfounded; Latterell cautions that providing a course shell or other standardized materials, especially in the absence of theory courses, may problematically discourage pedagogical engagement. But my findings suggest that, at least in this case, extensive autonomy in the absence of support did not consistently push instructors to engage thoughtfully with pedagogy: on the whole, new instructors were not so much making informed choices as grasping at straws.

This does not mean that the 2018-2019 iteration of Perspectives was without merit. A “heftier” common text would offer new instructors more guidance, but could limit how much instructors could tailor their courses, increase costs for students, and discourage critical engagement with pedagogy. But this study revealed some middle ground with additional support for new instructors was clearly needed. Though institutional limitations prevented the program from requiring a practicum at the time of this study, participants in my study suggested a number of creative alternatives the program might explore, including creating optional online training for instructors to review over the summer; improving professional development and its connection to Perspectives; developing more robust resources such as sample syllabi, assignments, and class activities; identifying recommendations for readings instructors could add to their courses to supplement Perspectives; or creating an instructor manual to accompany Perspectives that would help illuminate underlying pedagogical concepts and give additional recommendations for day-to-day practices. These resources would provide the more concrete support needed by new instructors and bolster their disciplinary knowledge while still pushing instructors to make critical choices in their pedagogy, consistent with Latterell’s recommendation to “strike a balance between providing GTAs with practical skills and advice and helping them understand the writing theory and pedagogy grounding those skills” (20).

My findings also make clear the importance of clearly establishing programmatic expectations for use of a common text. In the absence of clear guidance and oversight of the use of Perspectives, some instructors opted to not use it and did not meet expectations, while others worried unnecessarily that they were not meeting expectations. Greater guidance could easily be provided by increasing training and/or written guidance on use of Perspectives.

4.2 The Benefits of a Local Text

The authors appreciated that a common text gave a visible incarnation of the program’s values and curriculum for diverse stakeholders, including students, instructors, and even university administrators. Though my study cannot speak directly to the effects of Perspectives on other stakeholders, instructors certainly seem to have gained some shared understanding of the program and its curriculum from Perspectives, albeit to varying degrees; it is unclear from this study whether a non-local text would have had the same effect.

Equally importantly, the authors envisioned that the process of producing a text locally could generate a sense of unity across the disparate constituencies in the program and generate critical engagement with pedagogy. They saw the drafting process as a space for collaborative negotiation of the curriculum and values of the program, reminiscent of Latterell’s suggestions for challenging “traditional administrative power structures” and building teaching community.

However, my findings suggest that instructors’ engagement with Perspectives and feeling of ownership was highly dependent on their knowledge of and interaction with the drafting process. The initial drafting of Perspectives did provide an opportunity for engagement: instructors I interviewed who had been employed in the program when Perspectives was drafted felt that they had been given opportunities to engage in its development and generally spoke about it positively. But by the time of my study three years later, instructors who had not been present when Perspectives was drafted—the vast majority—were largely unaware that it was meant to incorporate their approaches and insights, instead seeing it as a top-down mandate. This perspective is reflected in comments like “this is a required textbook and I have no say in the matter.”

The program did make continual efforts to involve instructors in revision of the text by distributing a survey on Perspectives each year to solicit feedback. However, although instructors shared useful feedback with me, they typically did not communicate it to the program; administrators reported minimal survey responses, and many instructors told me they were uncomfortable offering feedback. One instructor stated, “I don’t think that people give critical feedback about [Perspectives] to the department. Especially graduate students, because we’re vulnerable.” Instructors outside Writing Studies or who didn’t identify pedagogy as a research area sometimes felt that it “wasn’t their place” to offer feedback. Ultimately, instructors seemed more likely to respond to perceived problems with Perspectives by using it minimally, or not at all, than by engaging with the program to push for changes.

To continue realizing the benefits of a locally, collaboratively drafted text, the program could more actively involve a changing instructor population in revision of Perspectives by more clearly describing the text as collaborative, integrating the feedback process into professional development sessions, or even making some revisions after fall semester to involve instructors teaching for only one year. This process would both be enriched by and contribute to overall efforts to improve instructors’ pedagogical knowledge: instructors would be better prepared to contribute if they had greater disciplinary knowledge, and would benefit from the process of thoughtful reflection on pedagogy involved in the revision.

4.3 Publication Format

Other genres besides a textbook might achieve some of the same goals: for example, Part I could be published as a statement of program values, and Part III could be adapted for use as a handout in library workshops. Certainly, then, a textbook is not the only means to fulfill the instructor preparation function of Perspectives. However, selecting or authoring one’s common textbook with instructor preparation in mind is a sensible choice, given that new instructors are likely to rely heavily on the text (Lynch-Biniek; Taggart and Lowry) and all instructors will engage a common text.

One frequently suggested change was making Perspectives a free online resource. This change would improve accessibility and address concerns about cost raised by many instructors. An online format also allows the flexibility to link to open-access texts or texts available to students through the library, connecting the text more clearly to broader disciplinary knowledge and improving the overall level of detail. And transitioning to an online format would make revisions easier and more visible, contributing to efforts to engage more instructors in the revision process, and demonstrate the program’s responsiveness to instructor feedback. For this program and others using custom texts, it is well worth exploring the affordances of an online version.

4.4 Takeaways for WPAs

My findings indicate both benefits and drawbacks of a common text in the program I studied: Perspectives worked to communicate local curriculum and values, especially to graduate and professional instructors with some pedagogical and disciplinary knowledge, but was less effective for new instructors who needed greater support and struggled to pick up on values alluded to in Perspectives.

As case study results, these findings are limited in their generalizability. Variables such as the brevity of Perspectives and structure of other instructor preparation efforts certainly affected my results and would not be applicable to all programs with common texts or even custom common texts. Future studies should explore the impacts of varying common texts, including “heftier” texts that provide much greater detail. Still, these findings suggest important initial takeaways for WPAs at a variety of institutions, especially if they have implemented or are considering implementing a common text as part of their programs.

First, this case confirms Yancey’s statement that common textbooks cannot be ignored in studying or evaluating instructor preparation, as they have often been historically. As we should expect, a textbook alone cannot meet all instructors’ needs for pedagogical support. But textbooks do play an important role in establishing program culture and values and norming content covered in courses. Textbooks are especially significant for experienced and professional instructors, who often do not participate in practica or other instructor preparation (Cicchino). WPAs should consider the needs of various constituencies of instructors in selecting a common text, and may find a shorter text supplemented with optional resources to be a useful option, especially for programs with many experienced instructors.

Second, this case highlights the importance of carefully considering and communicating the role a common text should play in instructors’ courses. Faced with a common text, some instructors will feel great freedom to set it aside and structure their courses as they wish, while others may feel significantly constrained, even if that is not the program’s intention. Thus, programs must set specific expectations to norm instructors’ use of a text and make clear where instructors have autonomy. Relatedly, programs should consider what role common texts play in instructor preparation more broadly, ensuring that new instructors have guidance in how to utilize and supplement the textbook effectively and that underlying pedagogical and disciplinary knowledge is made explicit to instructors.

Third, this case indicates benefits of a locally authored custom text, including highlighting program values and improving curricular consistency. Such texts may be especially useful in programs with limited time and resources for instructor preparation—a challenge faced in many programs (Cicchino), including the one considered in this study. In such programs, a locally authored textbook and other written documentation can provide a low-cost mechanism to communicate program approach and values. This study also suggests that a locally authored textbook could function as a mechanism for generating engagement and decentering administrator authority, though careful design of the writing and revision process is necessary to realize these goals.

Finally, this study reaffirms arguments like Cicchino’s about the importance of ongoing assessment of any instructor preparation strategy. Administrators were frequently surprised by my findings, including information about how Perspectives was utilized and gaps in communication between the program and instructors. These findings went beyond the information the program had previously collected and were taken into account in multiple ways in revising Perspectives, demonstrating the value of robust assessment of instructor preparation generally and of common textbooks specifically.

Appendices

Appendix A: Survey of Instructors

Demographics

Are you a graduate instructor or [professional instructor][8]?

graduate instructor

[professional instructor]

(If a graduate instructor) In which graduate program are you currently enrolled?

American Studies PhD

English PhD

English MFA

[Writing Studies] MA

[Writing Studies] PhD

Teaching Experience

Prior to this semester, in how many semesters had you taught at least one section of University Writing at [institution]?

0

1 semesters

2-4 semesters

5+ semesters

Prior to this semester, how many semesters had you taught at least one section of first-year writing at any institution other than [institution]?

[same options as #3]

Use of Perspectives—Quantitative Questions

In which of the following ways (if any) do you use [Perspectives] in your first-year writing class(es) at [institution]? Check all that apply.

Assign readings from [Perspectives]

Discuss readings from [Perspectives] in class

Refer students to [Perspectives] as a resource

Other

I do not use [Perspectives] in my class(es).

Which section(s) of [Perspectives] do you assign students to read?

Part I—Introduction to FYW

Part II—Process & Rhetorical Situation

Part III—Research and Writing

Part IV—Documentation Style (MLA & APA)

Part V—Sample Student Essays

Which section(s) of [Perspectives] do you discuss in class?

[same options as #6]

Which section(s) of [Perspectives] do you refer students to as a resource?

[same options as #6]

Which topic(s) in [Perspectives] do you cover in your course (whether or not you use [Perspectives] to cover these topics)? Check all that apply.

Introduction to the course

Process

Rhetorical situation

Research process

MLA and/or APA documentation

Sample student essays

None of the above

For which topic(s) in [Perspectives] do you provide supplemental materials (outside material used in conjunction with [Perspectives])?

[same options as #9]

For which topic(s) from [Perspectives] do you provide alternative materials (outside materials used instead of [Perspectives])?

[same options as #9]

Use of Perspectives—Qualitative Questions

What role does [Perspectives] and the material from [Perspectives] play in the first-year composition course(s) you are teaching this semester? Why did you give [Perspectives] that role?

Have you changed the role [Perspectives] and the material in [Perspectives] play in your University Writing course(s) over time? Why or why not?

In what ways does [Perspectives] fulfill your expectations for a mandatory text? In what ways does it not fulfill your expectations?

Perception of Perspectives—Quantitative Questions

For these questions, participants indicated responses on a four-point Likert scale from totally disagree to totally agree.

When I began using [Perspectives], it reflected my understanding of the aims of first-year writing.

[Perspectives] reflects my current understanding of the aims of first-year writing.

Reading [Perspectives] helped me understand the culture of the First-Year Writing Program at [the institution].

[Perspectives] gave me insight into what content should be included in University Writing at [the institution].

[Perspectives] gave me insight into pedagogical approaches to first-year writing.

Perceptions of Perspectives—Qualitative Questions

How did reading [Perspectives] affect your understanding of the culture and content of University Writing at [the institution]?

Did [Perspectives] provide information that could have helped you in teaching first-year composition at other institutions in the past and/or that could apply to teaching first-year composition at other institutions in the future? If so, what information?

What other factors influenced your approach to teaching first-year writing?

Appendix B: Interview/Focus Group Questions for Instructors

What do you think of [Perspectives]?

Summarize [Perspectives] for me. What do you see as the primary messages or takeaways of the book?

Summarize the program’s position on [Perspectives] for me. How does the program expect instructors will use the book? How does it communicate those expectations?

When did you start using [Perspectives] in your classroom? What were your initial thoughts on the book?

What do you think of [Perspectives] now? How do you currently use it in your class? How did you decide when and how to use [Perspectives] in your class?

Have you changed how you use [Perspectives] over time? Why?

Tell me about your experiences using [Perspectives] in your course.

Does [Perspectives] reflect your approach to composition? How easily does it fit into your class?

Do you feel [Perspectives] speaks to you as an instructor? To your students?

Does [Perspectives] help you accomplish your goals for your class?

What materials other than [Perspectives] do you use?

Are there times where you use alternate materials instead of [Perspectives]? Can you tell me about what materials you use instead and why you decided to do so?

What problems do you see with [Perspectives]? How would your ideal common text differ from [Perspectives]?

Do you think [Perspectives] gave you any insight into how to teach composition at [institution]? Why or why not?

Do you think [Perspectives] gave you any insight into how to teach composition that would apply if you taught composition at another institution? Why or why not?

Did [Perspectives] help you in designing your course?

Did you feel restricted by [Perspectives] in designing your course?

Interviews and focus groups were semi-structured; I also asked follow-up questions to elaborate on emerging themes and clarify meaning.

Appendix C: Interview Questions for Perspectives Authors

Summarize [Perspectives] for me. What do you see as the primary messages or takeaways of the book?

Summarize the program’s position on [Perspectives] for me. How does the program expect instructors will use the book? How does it communicate those expectations?

Tell me about the process of developing [Perspectives]. Why was [Perspectives] developed? What was your role? What was the motivation for developing the text?

What do you think of the book in its current state? What would you change about it?

How do you see the book being used by instructors? Are you happy with how it’s being used, or did you have a different vision?

How do you use the book in your own classroom? Has this changed over time? How does it help you achieve your goals for your course?

Interviews and focus groups were semi-structured; I also asked follow-up questions to elaborate on emerging themes and clarify meaning.

Appendix D: Full Coding Scheme

This list captures my full coding scheme, including both broad coding categories and subcodes.

- Autonomy/choice/restriction

- Program oversight

- Required text

- Descriptions of Perspectives

- Comparison to other texts

- Expressed and implicit values

- Level of detail

- Local

- ‘Real’/tangible

- Development of Perspectives

- Collaboration

- Opportunities for and reception of feedback

- Ideal common text

- Impact of Perspectives on instructors

- Change over time

- Confusion and uncertainty

- Innocuous, minimal impact

- Norming

- Other pedagogical influences outside Perspectives + FYW

- Potential takeaways for instructors

- Perspectives as instructor preparation

- Instructor feedback on how Perspectives works for students

- Cost of book

- Critical feedback

- Positive feedback

- Program intentions, expectations, and communication about Perspectives

- Program optics (“we want to appear as if”)

- Role in course

- Decision-making about role in course

- Other course materials used

- Parts of text used

- Synchrony or dissonance with approach

- Synchrony or dissonance with other content and materials

- Student feedback on Perspectives

- Cost of book

- Critical feedback

- Positive feedback

- Student policing of use of book

- Support structures around Perspectives

Notes

[1] Perspectives is a pseudonym title suggested by one of the textbook’s authors.

[2] For this study, I did not include some standard demographic questions (race/ethnicity, gender, etc.) to preserve participants’ anonymity in a fairly small population with limited diversity.

[3] Since some survey participants also participated in interviews, totals may not be the sum of the previous lines. Focus group participants were not asked if they had participated in the survey to protect anonymity, so it is possible some were double-counted.

[4] The total number of Writing Studies graduate instructors interviewed exceeds the number of Writing Studies graduate instructors in the FYW program in Spring 2019 because I interviewed three former FYW instructors from Writing Studies who volunteered to participate.

[5] Since some survey participants also participated in interviews, totals may not be the sum of the previous lines. Focus group participants were not asked if they had participated in the survey to protect anonymity, so it is possible some were double-counted.

[6] The concepts both appear in Part II of Perspectives, so some instructors may have used sections of Part II pertaining to only one of the two included concepts.

[7] Nine of these instructors at least assigned Perspectives as reading. Five more referred to the text as a resource, but did not discuss it with students, which may explain why the number of instructors (14) who reported they sent students to that section is greater than the number of instructors (12) who reported covering documentation with students.

[8] Brackets indicate that institution-specific language used in the original survey has been pseudonymized or replaced with a more general term.

Works Cited

Allen, Howard B. Preparing the Teacher of Composition and Communication: A Report. College Composition and Communication, vol. 3, no. 2, 1952, pp. 3–13.

Bleich, David. In Case of Fire, Throw In (What to Do with Textbooks Once You Switch to Sourcebooks). (Re)Visioning Composition Textbooks: Conflicts of Culture, Ideology, and Pedagogy, edited by Xin Liu Gale and Fredric G. Gale, State University of New York Press, 1999, pp. 15–42.

Burrows, Cedric. How Whiteness Haunts the Textbook Industry: The Reception of Nonwhites in Composition Textbooks. Rhetorics of Whiteness: Postracial Hauntings in Popular Culture, Social Media, and Education, edited by Tammie M. Kennedy, Joyce Irene Middleton, and Krista Ratcliffe, Southern Illinois University Press, 2017, pp. 171–181.

Cicchino, Amy. A Broader View: How Doctoral Programs in Rhetoric and Composition Prepare their Graduate Students to Teach Composition. Writing Program Administration, vol. 44, no. 1, 2020, pp. 86–106.

Conference on College Composition and Communication. CCCC Statement on Preparing Teachers of College Writing. Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2015, https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/statementonprep. Accessed 27 September 2021.

Fountainhead Press. Custom Solutions. Fountainhead Press, 2020, https://www.fountainheadpress. com/custom-solutions/. Accessed 27 September 2021.

Gale, Xin Liu, and Fredric G. Gale. (Re)Visioning Composition Textbooks: Conflicts of Culture, Ideology, and Pedagogy, State University of New York Press, 1999.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Berkenstein. They Say/I Say. 5th ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2021.

Latterell, Catherine G. Training the Workforce: An Overview of GTA Education Curricula.Writing Program Administration, vol. 19, no. 3, 1996, pp. 7–24.

Lunsford, Andrea A., et al. Everyone’s an Author. 4th ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2023.

Lynch-Biniek, Amy. Don’t Rock the Boat: Curricular Choices of Contingent and Permanent Composition Faculty. Academic Labor: Research and Artistry, vol. 1, 2017.

Powell, Katrina M., et al. Negotiating Resistance and Change: One Composition Program’s Struggle Not to Convert. Preparing College Teachers of Writing: Histories, Theories, Programs, and Practices, edited by Betty P. Pytlik and Sarah Liggett, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 121–132.

Pytlik, Betty P., and Sarah Liggett. Preparing College Teachers of Writing: Histories, Theories, Programs, and Practices. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Russell, Alisa LaDean. The Politics of Academic Language: Towards a Framework for Analyzing Language Representations in FYC Textbooks. Composition Forum, vol. 38, 2018, https://www.compositionforum.com/issue/38/language.php.

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd edition, Sage, 2016.

Taggart, Amy Rupiper, and Margaret Lowry. Cohorts, Grading, and Ethos: Listening to TAs Enhances Teacher Preparation. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 34, issue 2, 2011, pp. 89–114.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and J. Blake Scott. Defining and Developing Expertise in a Writing and Rhetoric Department. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 39, issue 1, 2015, pp. 72–93.

Welch, Kathleen E. Ideology and Freshman Textbook Production: The Place of Theory in Writing Pedagogy. College Composition and Communication, volume 38, issue 3, 1987, pp. 269–282.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. The Professionalization of TA Development Programs: A Heuristic for Curriculum Design. Preparing College Teachers of Writing: Histories, Theories, Programs, and Practices, edited by Betty P. Pytlik and Sarah Liggett, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 63–74.

Investigating Perspectives from Composition Forum 52 (Fall 2023)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/52/investigating-perspectives.php

© Copyright 2023 Jessa M. Wood.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 52 table of contents.