Abstract: In this article, I present the results of a national study of response to student writing and argue for an approach to response I call Responding for Transfer (RFT). My corpus includes peer and teacher responses to 1,054 rough and final drafts of student writing from across the curriculum as well as 128 student self-reflection essays from ePortfolios at seventy institutions of higher education across the U.S. I present evidence from this corpus to support my argument for an RFT approach that emphasizes student self-assessment, focuses teacher response on student metacognition rather than the products of drafts, and takes response into consideration in the design of vertical transfer curriculum.

The research on response makes a convincing case that, despite good intentions, college teachers across the curriculum waste much time and effort in their response to student writing. Research shows that teachers too often focus response on aspects of student writing that will have little long-term impact on learning, such as comments aimed at merely revising or editing discrete words, sentences, or paragraphs (Dohrer; Jeffery and Selting; Rysdam and Johnson-Shull; Stern and Solomon). Research indicates that students rarely apply teacher feedback to future writing contexts, and gains from teacher feedback are often small (Carless; Knoblauch and Brannon; Wingate). Although the literature on self-assessment shows that with guidance students are capable of effectively evaluating their drafts and monitoring their development as writers (Andrade and Evans; Thorpe), and that self-assessment improves student writing performance (Pope; Ziegler and Moeller), teachers across disciplines rarely involve students in response through self-assessment (Yancey, Getting Beyond). Research also shows students desire response they can apply to future writing contexts, but rarely receive comments from teachers that are aimed at transfer (Carless; Cunningham; Lizzio and Wilson; Vardi). Oftentimes teacher comments are focused on justifying grades (Brannon and Knoblauch; Orrell), which undermines transfer. A focus on grades may also lead to linguistic bias that negatively impacts BIPOC students (Condon and Young; Inoue; S. Wood).

Transfer and the teaching of writing have been the focus of much recent theory and research in Writing Studies, but the transfer literature has neglected the topic of response to student writing. The Writing Studies scholarship on transfer has emphasized writing and reading assignment design (Adler-Kassner et al.; Anson and Moore; Beaufort; Carillo; Moore and Bass; Wardle; Yancey et al., The Teaching for Transfer, Writing Across Contexts), but perhaps because this research has focused mostly on designing curriculum, the transfer scholarship has not delved into the role of responding in writing transfer. The one area of U.S. research on response that has seen an increased interest in transfer is writing center tutoring, including a transfer-themed issue of The Writing Lab Newsletter (Devet and Driscoll). International scholars have focused more attention on transfer and responding than U.S. scholars, with the concept of feedforward predominant in much international research. But feedforward research has tended to focus on teacher response that can be applied to the next assignment within a course, rather than response aimed at more far reaching transfer (Carless; Duncan; Vardi).

In this article, I present an approach to response that is aimed at promoting far reaching, vertical transfer—an approach I refer to as Responding for Transfer (RFT). RFT shifts the focus of response from teachers to students and from the genres students produce to students’ self-reflections about composing in those genres. RFT encourages teachers, academic departments, and institutions of higher education to be more intentional not only in the design of their learning outcomes and writing assignments, but also in the vertical design of response.

The RFT approach is based on my comprehensive review of the literature on response and a national study I conducted of teacher and peer response and student self-assessment. This study involves a qualitative analysis of a corpus of teacher and peer response to over 1,000 rough and final drafts of college student writing, as well as student self-assessment of their writing and reflections on the feedback they received from teachers and peers. In addition to introducing the RFT approach, in this article I address the call from Writing Studies scholars for more large-scale research into response to writing (Evans; Lang) and more research on how students react to teacher response (Anson; Formo and Stallings; Lee). I focus on the most striking finding from my analysis of the responses in my corpus: the disconnect between what types of response the research shows are most impactful and the ways that teachers in my study actually respond. This disconnect, and the evidence in my corpus of students’ ability to self-assess and reflect on growth and transfer, led me to develop the RFT approach. My hope is that the RFT principles I share will inspire teachers to refine or refocus their response in ways that will help students transfer what they have learned about writing to future writing contexts and encourage students to focus less on writing to get a good grade and more on writing to learn and grow.

A National Study of Response

My research corpus includes artifacts of teacher and peer response and student self-assessment from undergraduate college ePortfolios representing seventy institutions across the U.S. (see Appendix for a list of the institutions). The 240 portfolios I collected include 1,054 pieces of student writing with comments (635 teacher responses and 419 peer responses) as well as 128 student self-reflection essays and additional artifacts of student self-reflection in the form of process memos, revision plans, and introductory materials on individual web pages. Seventy percent of the responses are from first-year writing courses, and 30% are from courses across disciplines. This difference reflects the greater availability through internet searches of ePortfolios from first-year writing courses. Approximately 25% of the pieces of student writing are final drafts (n=193), with the rest being drafts in progress. The corpus includes a broad range of genres: literacy narratives, research articles, business reports, film reviews, literature reviews, and so on. I located these portfolios using internet key term searches such as “teacher comments,” “peer feedback,” and “reflection essay” combined with the term “portfolio.” Common platforms students used to create the ePortfolios in my corpus include Digiciation, WordPress, and Weebly.

I submitted an IRB protocol to my institution and the project was given “not human subjects” status by an administrative review. In a discussion of issues of consent in corpus studies using internet data, Tao et al. argue that accessibility of online research sites is an important determinant in whether informed consent is required (11). All of the artifacts I collected were existing data, published on the internet without password protection. The students who published these portfolios knew their work was going to be publicly available, and most of the portfolios include a welcome page in which the students introduce themselves to a potential broader readership beyond the course. An additional ethical issue in online research that Tao et al. discuss is the sensitivity of the topic being researched. Regardless of the human subjects exemption granted by my institution’s IRB process, had my research focused on a sensitive topic, I would not have conducted the study, given my inability to obtained informed consent. I do not criticize the students or their writing in my research, but rather provide examples primarily of the benefits of giving students a greater role in response.

Although the data in my corpus is public and not focused on a sensitive topic, as Tao et al. point out, even internet research data classified as public is on a continuum between private and public (13). Although they are not private or password protected, the ePortfolios in my corpus were published to meet a course requirement. Students using Digication might have had the option of choosing password protection or publishing for solely an institutional audience, whereas students using Google Sites or Weebly or WordPress did not have a privacy option. In the interest of protecting the privacy of the students and teachers, I anonymized all of the data, and I do not identify students or teachers by name or institution. In some portfolios students display graded work, which is technically a violation of FERPA, and I did not include in my examples shared in this article rough or final drafts that include a grade.

I began my research process by conducting a comprehensive review of the literature, reviewing over 1,300 books and articles on teacher and peer response and student self-assessment. I drew on themes from the scholarship to develop a heuristic for researching response and designing classroom response constructs, which I discuss in detail in the forthcoming monograph Reconstructing Response to Student Writing. In this article, I focus on a subset of evidence from my corpus related to self-assessment and transfer and the components of my heuristic that explore the following questions: “Who should respond to student writing?” and “What should response focus on?”

My process of analyzing the data consisted of three cycles: a quick initial read of the data in the context of the themes that emerged from the literature review; a second closer reading in which I made analytic memos in a spreadsheet that was organized based on my response heuristic (in the second cycle I revised my heuristic based on my findings, integrating metacognition and transfer more prominently); and a third cycle six months later that involved a “sense checking” (Creswell 192) of the validity of my analysis and heuristic with two Education Ph.D. students at my institution. We applied my heuristic to twenty randomized and stratified portfolios and conducted a peer debriefing that resulted in confirmation by the graduate students of the patterns I had noted in my heuristic.

Despite the size of my corpus, I cannot generalize about response to all of college writing in the U.S. However, I believe there are strong patterns in my study that are relevant for scholars and teachers interested in transfer, response, and self-assessment. A study of this scale cannot include the level of context of smaller-scale, ethnographic research, and in this respect my research is similar to other recent large-scale studies of response (Anson and Anson; Dixon and Moxley; Lang; Warnsby et al.). As was true for these researchers, I did not know the teachers’ or students’ intentions behind their comments or observe classroom interactions or response happening in conferences or office hours. However, unlike prior large-scale studies of response, I do have a degree of triangulation of data, given that my corpus includes students’ reflections on response and drafts and revisions of their writing.

Responding to the Draft versus Responding to the Writer

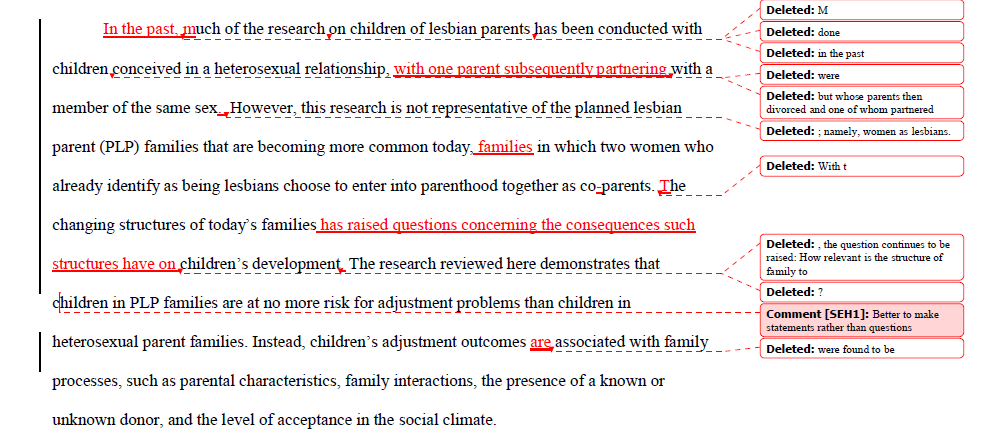

Frankenberg-Garcia notes that “feedback teachers give to students is usually based on first, second, or final drafts. This means that it is based on the outcome of the students' writing decisions, and does not address the decisions themselves” (101). Teachers in my corpus focus their response on outcomes: most often discrete parts of discourse, and especially words, sentences, and paragraphs. The following screenshots of responses to paragraphs from two different teachers in my research exemplify this approach:

These kinds of directive responses to discrete parts of written discourse can reinforce students’ misconception that a teacher’s purpose in responding is to correct students’ writing. As one student says in a reflection memo, “I made the corrections the professor suggested.” Another student writes in a reflection on teacher comments, “Dr. X does a very good job of pointing out what is wrong in a draft so that we know exactly what needs to be fixed.”

A focus on the writing and not the writer is true of most of the teacher comments on both drafts in progress and final drafts, but teacher end comments on final drafts stand out as almost always backward looking rather than feedforward:

More summary and synthesis of your key findings and observations at the end would have been helpful.

I could not find a clearly stated research question, though you state the motivation for the study was to explore the lived experience of off-campus students related to participation in fitness activities with on-campus recreational facilities. I would have liked to see this purpose turned into an overarching guiding research question.

Where this paper could have been improved is by focusing a little more on specific peoples rather than the early historical progression in which many people groups are lumped under one title for a period of time.

The research indicates that because these comments are written on a final, graded draft, in future assignments students will be unlikely to address the concerns expressed by these teachers (Ferris, Polio, Price et al.).

The portfolios in my corpus often include reflective writing in the form of process memos, self-assessments, and literacy narratives, but instructors rarely connect their response to students’ reflections on their literacy histories and their self-assessments of their strengths and challenges as writers. Consider how the following passages from reflective writing might have led to more effective teacher response, had the instructors in my study made connections between their comments, students’ literacy histories, and transfer of writing to future contexts:

Growing up in an Indian immigrant household, I did not have many opportunities to converse in the English language. Since English is my third language, I face many challenges both speaking and writing the language on a daily basis. When I began [FYC], I was nervous that I would not be able to survive through the ten weeks of rigorous research and writing.

As a student speaking English as a second language, I have always had issues with writing papers and communicating with people effectively. This has been a continuing interest for me while taking this course. Consider how difficult it would be to communicate words that have not direct translation into another language.

In addition to sharing perspectives on linguistic and cultural diversity, when students reflect on their literacy histories and processes, they may disclose valuable information for teachers regarding documented or undocumented learning differences. Wood and Madden found that students wanted more opportunities to openly discuss their disabilities with teachers, and Hitt argues for making space for disclosure of disabilities (26).

Teachers in my study do not make connections between their responses and students’ prior experiences with literacies, and may even inadvertently undermine transfer by focusing on sentence-level error with language learners who are nervous about their fluency in English. Teachers also undermine transfer by devoting so much of their commenting to graded, final drafts that offer no further opportunity for applying feedback. In artifacts of self-reflection in my corpus, it is striking how many students associate teacher feedback primarily with grading.

Grading Undermines Transfer

Research has found that teachers’ comments often focus on justifying grades rather than on student growth (Brannon and Knoblauch; Orrell), that many students care about feedback only as it relates to improving their grade (Burkland and Grimm; Cunningham), that grading has the effect of reducing self-efficacy and decreasing motivation to learn (Bowden; Lipnevich and Smith), and that grading is racist when it relies on a single, dominant white standard (Inoue; S. Wood). I found that the largest obstacle to student growth and transfer is students’ understandable perception that their primary goal is to please the teacher in order to get an “A.” One student spells out this narrow view of the teacher as judge in their portfolio reflection: “As far as the essays that are included in my E-portfolio, again they are developed and fixed to please my target audience, Professor X.” In a final reflection on their teacher’s comments, a student with a similar philosophy writes, “Knowing what the teacher wants from an assignment is really helpful. You can alter your work to fit the teacher’s expectations.” In a midterm reflection, another student echoes this focus on grades:

After the midterm and as the quarter has moved on I feel like I have a better understanding for my target audience for this class, which is my teacher Professor X. I have been focusing more on making my paper geared toward her ideals of a solid paper....By doing this it makes my professor happy and ultimately sets me up for a better grade.

Teachers are not considered by these students to be agents of transfer who can help them navigate future disciplinary discourse communities. Rather, they are authority figures to be pleased. This tendency for students to dwell on grades when interpreting teacher response is a focal point of a handful of studies on response (Bowden; Burkland and Grimm; Cunningham; Dohrer; Richardson), but I believe that not enough has been made in the response or transfer literature of the disconnect between our goal of having students transfer our advice to future writing situations and students’ perceptions of us as judge and jury.

Assigning students recognizable disciplinary, professional, or public genres written to specific wider audiences is one way that a handful of teachers in my corpus discourage students from seeing them as merely graders. A first-year writing teacher illustrates this point with their response to an assignment that asks students to write a proposal to a campus organization. The teacher writes in an end comment of a proposal aimed at the university’s student government, “The only suggestion I have for you is to consider your audience as you revise, especially the beginning of the essay. I think your introduction would appeal to a general audience, but where and when does SGA step in? Try to make the first couple of paragraphs more relevant to the specific situation you are writing for.”

A professional writing student, reflecting on feedback they received from the teacher on a résumé, speaks to students’ perceptions of the usefulness of feedback that is given on an assignment that will eventually be circulated to an audience beyond the classroom. The student writes, “I feel that after having this assignment I will be better equipped to make sure my resume isn’t one of those that gets thrown in the trash because of a simple formatting mistake. I used Dr. X’s advice to update my own resume and feel that it is more useful after having done so.” This student’s appreciation for the teacher’s advice contrasts with the attitude of the students I cited earlier who are focused on pleasing the teacher in order to get a good grade.

A Scarcity of Comments on Transfer

Of the 635 pieces of writing in my corpus that teachers responded to, and the thousands of teacher comments I analyzed, there are only a dozen comments that focus on transfer to future writing contexts. Most of these are end comments that focus on the transfer of writing strategies to the next assignment within the course. What follows are examples of these type of feedforward comments:

Next time, please allow time toward the end of your revision process to find your clearest presentation of your claim, and add it to the introduction.

In Paper 2, build on your strong eye for literary detail by applying it to a clearly-articulated debate.

In the next paper, focus on making your writing as clear and succinct as possible.

Students consistently show evidence in the drafts they include in their ePortfolios of applying teachers’ transfer-focused comments to the next writing assignment in the class. There is some indication from the literature that students will apply these types of comments to their writing in future courses as well (Freestone; Cunningham), but the literature emphasizes that far reaching transfer is more likely to occur if it is cued and explicit (Beaufort; Fishman and Reiff; Perkins and Salomon).

The type of comment I argue should be the most common in response to college writing is the rarest type in my study: response that is explicitly meant to encourage transfer of writing strategies and knowledge beyond a course. In the hundreds of pieces of students’ writing and thousands of comments in my corpus, there are only two content-focused teacher comments that focus on the student as a writer beyond the current course. These more far reaching transfer comments emphasize strengths in students’ writing that will be relevant to their future academic careers:

This is a poetic move, you have some bold language moments in this paper, you might try to grow this impulse as your write at university more and more, balancing it with acute thinking. The tension this would create will take you far.

You write with a sense of purpose and you make really excellent connections to other texts we've read in class. These are your strengths as a writer and something you should be proud of and keep in mind when you compose your next papers in your academic career.

In my review of the response literature, I was struck by how few of the teacher comments shared in forty years of empirical studies of response focus on far reaching transfer. My own research provides further confirmation that college teachers almost never give response that explicitly points to future writing contexts beyond the next assignment in the course.

Student Self-Reflection on Transfer

The students in my research are more likely to consider transfer than teachers. In artifacts of metacognition included in their portfolios, students are very much aware of how they transferred knowledge and skills from one task to the next, as these passages from students’ reflective writing illustrate:

When we moved onto more lengthy papers such as a research paper it was helpful to have the background that the previous papers have provided such as outline techniques, peer edit methods, and writing center advice.

Also, my goal of being argumentative comes up here as this draft lacked a thesis that was argued throughout. This was I point I took to heart and tried improving it not only in the second draft but throughout the rest of the course.

Another common theme in student self-reflections is transfer to other courses:

The most valuable thing I learned during the process of writing this paper was the thesis progression....This is a process I have already applied to other classes and will continue to use for the rest of my education.

The knowledge and resources I obtained in this course is helpful in both, my academic and professional career. For example, in my upper-division Sociology course, I was able to successfully apply my skills learned about using credible resources to conduct a literature review regarding the perception of success among children of immigrants.

Students are also able to consider transfer of writing knowledge and skills to their lives after college. In their portfolio reflection essays, students often comment on how what they have learned about writing will be applicable in their future careers:

I found this assignment to be very practical and helpful. I am planning on using what I have learned from this project to try and get an unsolicited position and The Center for Addiction and Recovery right here on X campus.

Overall, the work involved in performing this research will help me in the future.... These methods of writing skills and outside research will prove beneficial when I enter the health care profession and continue writing academic papers relevant to the suitable audiences.

Students are also able to connect peer response and transfer. Sometimes transfer meant using a peer comment made on one section of a piece of writing and applying it to other sections. In a reflection on peer feedback, one student writes, “My first draft for Paper 3 was incomplete. Very incomplete. Therefore the [peer] feedback I got on it was only related to the first sub-claim I was arguing. However, the feedback for the first sub-claim guided me through my second sub-claim; I made sure not to make the same mistakes.” In this student’s second draft after receiving peer response, they organized what were a few rambling paragraphs for the first sub-claim into three focused and developed paragraphs, and they went from including a single reference to a secondary source to support their first sub-claim to drawing on the secondary source multiple times in each paragraph. This same approach was applied to the second sub-claim in the revised draft.

Students were also claiming to transfer comments they received from peers to future drafts and to future writing tasks. One student was able to articulate their ability to transfer peer feedback to future writing assignments. In a reflective portfolio introduction, the student writes:

In the peer review above, my classmate had made great suggestions on how I should improve my paper for the second draft of Comp I. He commented on how I should add transitions sentences to help with the flow of my paper. When I talked about the three different Supreme Court cases, I just listed them out without making connections from one to another. This is something I must be careful of on future papers because I tend to go off on a tangent by not mentioning my evidence’s connection with my purpose and claim.

Perhaps transfer was more likely to occur from peer feedback than instructor comments due to the fact that in most of the courses in my research peer feedback is more interactive than teacher feedback and more focused on content rather than sentence-level concerns.

In addition to receiving peer response in most of the courses in my study, many students sought out feedback from their campus writing center. Students in my study frequently reflect on the value of writing center tutor feedback, and a number of students are able to articulate how they applied tutor feedback to transfer knowledge about writing, as the following passage from a student reflection letter illustrates:

While at the Writing Center ... I was also taught that making the claim that contradicts my thesis can be powerful to my thesis if I can offer why that claim is inherently wrong. In this paper I decided to bring up the claim of shock factor and how the use of bold or even disturbing images may deter some but will attract many in the long run. I had never used a counter-argument as a persuasive strategy in writing before, but now it is something I try to include in all my papers for more positive overall conclusions.

In their response to student writing, teachers in my research usually recommend students visit the campus writing center for narrow editing concerns. The following end comments are representative:

Next time, work with a tutor in the writing center for proofreading purposes before submitting your final paper.

Your revision should also address the many grammatical and mechanical errors in the draft....I would definitely encourage you to work with a Writing Center tutor....

Unlike their teachers, in their portfolio reflection essays, students associate writing center feedback with global revisions and transferable writing knowledge and skills.

For the most part, teachers in my corpus give feedback in a hermetic seal, rarely considering transfer to the next assignment or beyond the course. But in their process memos and portfolio reflections, students show that they are fully capable of looking beyond teachers’ product-focused comments and connecting what they have learned to future writing contexts, both within and beyond the course.

Principles of Responding for Transfer

Kathleen Yancey bemoans that despite what we know about the research on metacognition, when we do ask students to self-reflect on their writing, “it tends to function as a supplemental or optional task, not as an integral and critical one” (Getting Beyond par. 11). RFT shifts the teacher’s role from judge and jury to designer of the response construct, and shifts the onus of response and assessment from teachers to students. RFT turns our primary commenting focus away from the rough and final drafts of the discrete genres we ask students to produce and towards entering into dialogue with students’ peer and self-assessments. RFT recognizes the harm that grades do to learning, growth, and transfer, and looks for ways to deemphasize grading. RFT connects teacher response to students’ literacy histories, and requires that teachers become more aware of inequities students have faced in their prior literacy experiences and that teachers make more space for students to disclose access needs. The concept of feedforward in international literature on response and recent interest in transfer in writing center scholarship have begun to point to a coherent approach to responding for transfer. My goal in this section is to both synthesize and extend discussions of response and transfer by outlining a set of ten principles for RFT.

Principle #1: Student self-assessment should be the center of the response construct.

Rather than focusing most of their response efforts on how to respond or how often to respond, teachers should focus on designing rigorous student self-assessment. In writing-focused courses in particular, assignments that ask for self-assessment will be more likely to promote transfer than any particular academic genre. For example, common Writing About Writing/Teaching for Transfer assignments such as a literacy inventory, a literacy narrative, a theory of writing essay, or a portfolio reflection essay. Teachers in the disciplines should consider integrating reflective genres that connect to their disciplines. For example, field journals, personal mission or philosophy statements, artists’ statements, experiment logbooks, and skills inventories.

As teachers assess students’ self-reflections, they should keep in mind Yancey’s cautions not to view reflection as merely assimilation to academic discourse norms. Yancey argues for a conception of reflection that is both individual and social, and engages with cultural contexts in a process of not just replicating the university but reinventing it (Introduction 10-11). Inoue and Richmond argue that “most reflective discourses expected in writing classrooms are white discourses,” whether that means BIPOC students assessing themselves as deficient when their literacies do not conform to white practices or standards, or students having to fit into white discourse values of individualism, objectivity, and detachment. In self-assessments, students should be encouraged to question and critique hegemonic discourse norms.

Shifting the focus of the response construct to student self-assessment forces teachers to rethink their approach to grading. Ideally, writing teachers would not give grades at all, since grades impede transfer. But realistically, most teachers are required to reduce student performance to a final, one-dimensional grade. A useful grading approach for RFT, given the constraints almost all of us face, is labor-based contract grading. In labor-based contract grading, teachers shift more of the onus to the student to make an argument for the work they have done in the class, and to reflect on their labor and growth (Inoue). Both self-assessment and labor-based contract grading should be grounded in an antiracist assessment framework (Inoue; S. Wood) and should also consider the ways neurodiverse students’ ability to complete labor may differ from normative labor standards of a contract grading system (Kryger and Zimmerman; T. Wood).

Principle #2: Students should be prompted to think about growth and transfer throughout their writing processes.

Self-assessment is often used as merely a complement to teacher response. Only a handful of the courses in my research require students to self-assess from the first week until the culminating portfolio. Most students lack experience with self-assessment, and teachers would be wise to scaffold self-assessment so that tasks of student metacognition are carefully sequenced and build toward a culminating artifact of reflection. As Hilgers et al. argue, self-assessment should be systematic, frequent, integrated, and guided (6). In writing-focused courses especially, students’ self-assessment and their growing rhetorical awareness are more important and impactful than any particular revisions they make or any comments they receive from peers or the teacher regarding their sentences and paragraphs. Assigning reflective writing throughout a course will also mitigate against formulaic culminating reflections (Neal) and portfolio reflection letters that relate a pat “narrative of progress” (Emmons) seemingly meant to please the teacher. Reflective writing activities could include beginning of the course self-assessments, process memos included with drafts of formal assignments, revision plans completed after peer and teacher response, midterm reflections, audience analyses, literacy logs, literacy inventories, and reflective reading response journals. Yancey’s A Rhetoric of Reflection and Reflection in the Writing Classroom include ideas for a variety of reflective writing activities that are informed by research on transfer.

Principle #3: Peer response should play a greater role than teacher response.

My research adds further evidence to the scholarship that has shown that a prime benefit of peer response is metacognition and transfer (Ballantyne et al.; Lundstrom and Baker; Nicol et al). Peers should respond more than teachers respond, and teachers should respond only after peers have responded. To cue transfer, peer response should integrate reflective writing such as process memos and revisions plans. Peer response scripts can include questions that focus on transferable writing knowledge and skills. After receiving feedback from peers, students can be prompted to reflect on what advice they received from peers might transfer to future writing contexts. Teachers should reinforce peer feedback by asking students to include reflections on peer feedback when they submit a revised draft and teachers should engage in dialogue with peer feedback in their own responses.

Principle #4: Teachers should not respond until they are familiar with students’ literacy histories, beliefs, and habits.

Teachers in my study who assign first-week self-reflections or a literacy survey or an initial literacy narrative assignment gain valuable information in regard to what types of feedback might help each student with transfer. When teachers are aware of students’ language backgrounds, level of apprehension as writers, and prior experiences with writing, teachers can tailor their comments to improve the chances of transfer. Getting to know students before we provide formal response also helps in avoiding labeling and stereotyping (Kerschbaum). April Baker Bell’s “attitudinal assessment” is one example of a tool teachers can use to familiarize themselves with students’ beliefs about language and internalized language racism. Getting to know students’ literacy backgrounds can also provide an avenue for students to share access needs (Hitt 31). This may result in our adjusting of response modes to reach different types of learners with different needs (Price 95). In large courses, or courses where writing is not the primary focus, a simple and quick way to get a sense of the student as writer is to require a process memo, where a student reflects on the strengths and weaknesses of a draft.

Principle #5: When teachers do comment on student writing, they should focus their comments on growth and transfer.

Prior research on response and the evidence from my corpus indicates that college teachers rarely focus on growth and transfer in their response to student writing. Commenting on growth requires a familiarity with students’ literacy histories, knowledge of and interaction with the feedback students receive from peers on their drafts, an awareness of how drafts have changed over time, and an engagement with students’ own self-assessment of their growth and their continuing challenges.

At a basic level, almost any comment made on a draft can point to transfer. For example, a comment about improving MLA or APA citation style can elaborate on why the author is emphasized in humanities disciplines and the date is emphasized in social science disciplines. At a deeper level, comments in response to students’ own self-assessments are more likely to address the knowledge and habits we know from empirical research lead to transfer. These include comments about writing processes, the theories and beliefs students have about writing, and students’ ability to assess and monitor their drafting and revising processes.

Principle #6: Teachers should place more emphasis on responding to students’ self-assessments and less emphasis on responding to the content of rough and final drafts of discrete assignments.

My research and prior research on how teachers respond to student writing indicate that teachers devote a great deal of time to pouring over drafts of student writing, focusing on the paragraphs and sentences of discrete assignments. However, research has shown that product-focused comments do not often lead to growth and transfer. It would be more efficient for teachers and more beneficial for students as learners if we focus our response on assignments that ask for student self-assessment. Admittedly, in courses in the disciplines, helping students learn the conventions of specific disciplinary and professional genres is typically a much higher priority than it is in first-year writing courses, and thus teacher response may need to include a greater focus on responding to the rough and final drafts of specific genres. However, all teachers should prioritize responding to students’ own assessment of their writing. This emphasis on responding to students’ reflective writing is an extension of White’s argument in The Scoring of Writing Portfolios: Phase 2, although White’s concern is large-scale assessment and scoring, and understandably White is focused on a single artifact of reflection, whereas I am arguing for teachers engaging in dialogue with student self-reflection throughout a course.

Principle #7: The response construct should be designed to encourage dialogue rather than transmission.

There are a variety of ways teachers can engage in a dialogue with students when responding. Students can be asked to include process memos with drafts that discuss the feedback they received from peers and their own self-assessment of the draft (Yancey’s “Talk To” reflection activities in Reflection in the Writing Classroom provide a variety of options for these types of dialogues with students’ self-reflection). Teachers can use the affordances of digital tools such as the commenting and responding to comments functions of Word, Google Docs, etc. to ask students to comment on their own drafts and respond to our comments (Yancey’s “Talk Back” activities provide a variety of ways for students to reflect on our response). Perhaps the most powerful way to include dialogue in the response construct is through one-one-one or small group conferences with students, either face-to-face or via a video conferencing platform. Peer response and writing centers also provide valuable spaces for response dialogue. Simply collecting a draft and writing comments and then returning those comments to the student reduces the chances of transfer and development.

Principle #8: The response construct should be designed to include audiences beyond the teacher.

Writing to please the teacher and obtain a good grade is in direct opposition to writing to learn, grow, and transfer knowledge to future contexts. The obsession with grades and with pleasing the teacher shown by the students in my research reveals that even when teachers are playing the role of disciplinary mentor and not the role of examiner, students will often perceive us as merely graders, each with our own idiosyncratic expectations. An explicit way to illustrate to students the ways that writing abilities transfer to contexts beyond the classroom is to assign projects that demand that students write in recognizable genres that exist outside of the classroom and to audiences beyond the teacher, rather than assign what Wardle refers to as “mutt genres” that do not present students with authentic rhetorical situations. Some examples include blogs, websites, service learning projects, writing for internships, writing for scholarships and grants, résumés and professional websites, writing for social media, and writing for political activism. Teachers can also create hypothetical rhetorical situations in genres that students will encounter outside of the classroom and respond in the role of the wider audience: for example, role-playing the editor of a journal or the CEO of a company or the readers of a particular blog or magazine or website.

Principle #9: The campus writing center should be a central part of the response construct.

Empirical research has shown that writing centers play an important role in students’ growth as writers and in their ability to transfer knowledge about writing (Henson and Stephenson; Tiruchittampalam et al.; Young and Fritzsche). One-on-one work with a writing center tutor encourages dialogue and transfer. The writing center should be considered a central part of the response construct for all students and for every course. Writing center tutors should receive training in ways to respond that encourage transfer, and tutoring for transfer should be a primary goal of writing centers (Busekrus; Devet). In their introduction to the Writing Lab Newsletter special issue on transfer, Devet and Driscoll provide an overview of factors writing centers should take account for encouraging transfer: the students and their knowledge and dispositions, the genres of writing, transfer-focused structures and supports, and tutor knowledge about transfer.

Principle #10: Response and self-assessment should be a central part of the design of a programmatic and vertical curriculum.

The Writing Across the Curriculum movement has promoted the vertical integration of writing in departments and across an entire institution, from first-year writing to General Education writing requirements to writing-intensive requirements or Writing Enriched Curriculum initiatives. However, response is often neglected when we think about vertical design of writing curriculum. Only a handful of scholars have focused on the design of response at the institutional level (Hyland and Hyland; Irons; Rust et al.; Séror; Walker; Williams and Kane). Constructing response for vertical design in departments and across institutions might mean developing shared metalanguage for responding; creating shared rubrics; making connections for students among what is taught in the different courses in our department when we respond to their writing; developing departmental and career student ePortfolios; and promoting pedagogies of response that can be implemented across a department, program, or institution, such as peer response, portfolio assessment, or contract grading.

In outlining these principles of an RFT approach, I do not wish to present a dogma. RFT represents a shift in thinking about the design of the response construct, but this shift can happen in varying degrees, and will depend on the teacher, the discipline, the course, and the student population. For some teachers, the idea of RFT might simply lead to assigning artifacts of metacognition and considering students’ own self-assessments in their response to students’ drafts. Other teachers may find that shifting the entire focus of their response from the drafts of discrete genres to students’ reflections on these drafts may lead to greater student growth and transfer. A department or institution might start small in regards to implementing vertical response by simply creating a shared rubric or promoting the use of peer response in every course or every discipline. Or an institution may be ready to take more substantial steps, such as implementing a career ePortfolio. Regardless of the implementation approach, RFT represents a fundamental shift in the focus of our response: from teachers to students, from products to processes, from discrete genres to artifacts of metacognition, and from teachers as graders to teachers as agents of transfer.

Appendix: Institutions Included in the Research

Alvin Community College

Alverno College

Arizona State University

Bloomsburg University

Boise State University

Boston University

Brigham Young University

California State University-Long Beach

California State University-Fullerton

California State University-Northridge

College of Southern Idaho

College of Southern Maryland

Colorado State University

Dartmouth

DePaul University

Elizabethtown College

Fairfield University

Ferris State University

Fresno State University

Grand Canyon University

Iowa State University

Kingsborough Community College

Lewis and Clark College

Manhattanville College

Mercy College (NY)

Miami University

Mississippi State University

Mount Mary University

North Carolina State University

Northeastern University

Norwalk Community College

Ohio State University

Oregon State University

Otis College of Art and Design

Penn State University

Rowan Cabarrus Community College

Rutgers

Sacramento State University

Salem State University

Salt Lake Community College

Santa Clara University

Seton Hall University

Skidmore College

South Piedmont Community College

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda, et al. The Value of Troublesome Knowledge: Transfer and Threshold Concepts in Writing and History. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/troublesome-knowledge-threshold.php.

Andrade, Maureen S., and Norman W. Evans. Principles and Practices for Response in Second Language Writing. Routledge, 2013.

Anson, Chris M. What Good is it? The Effects of Teacher Response on Students’ Development. Writing Assessment in the 21st Century: Essays in Honor of Edward M. White, edited by Norbert Elliot and Les Perelman, New Hampton Press, 2012, pp.187-202.

Anson, Ian, and Chris M. Anson. Assessing Peer and Instructor Response to Writing: A Corpus Analysis from an Expert Survey. Assessing Writing, vol. 33, 2017, pp. 12-24.

Anson, Chris M., and Jessie L. Moore, editors. Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer. University Press of Colorado, 2016.

Baker-Bell, April. Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy. NCTE-Routledge, 2020.

Ballantyne, Roy, et al. Developing Procedures for Implementing Peer Assessment in Large Classes Using an Action Research Process. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 27, no. 5, 2002, pp. 427-441.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State UP, 2007.

Bowden, Darsie. Comments on Student Papers: Student Perspectives. Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 11, no. 1, 2018, https://journalofwritingassessment.org/article.php?article=121.

Brannon, Lil, and C.H. Knoblauch. On Students’ Rights to their Own Texts: A Model of Teacher Response. College Composition and Communication, vol. 33, no. 2, 1982, pp. 157-66.

Burkland, Jill, and Nancy Grimm. Motivating Through Responding. Journal of Teaching Writing, vol. 5, 1986, pp. 237-247.

Busekrus, Elizabeth. A Conversational Approach: Using Writing Center Pedagogy in Commenting for Transfer in the Classroom. Journal of Response to Writing, vol. 4, no. 1, 2018, pp. 100-116.

Carillo, Ellen C. Securing a Place for Reading in Composition: The Importance of Teaching for Transfer. Utah State UP, 2014.

Carless, David. Differing Perceptions in the Feedback Process. Studies in Higher Education, vol. 21, no. 2, 2006, pp. 219-33.

Condon, Frankie, and Vershawn Ashanti Young, editors. Performing Antiracist Pedagogy. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2017.

Creswell, John W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 3rd ed., SAGE Publications, 2009.

Cunningham, Jennifer M. Composition Students’ Opinion of and Attention to Instructor Feedback. Journal of Response to Student Writing, vol. 5, no. 1, 2019, pp. 4-38.

Devet, Bonnie. The Writing Center and Transfer of Learning: A Primer for Directors. The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, 2015, pp. 119-150.

Devet, Bonnie, and Dana L. Driscoll, editors. Transfer of Learning in the Writing Center. Writing Lab Newsletter, 2020, https://wlnjournal/digitaleditedcollection2/.

Dixon, Zachary, and Joe M. Moxley. Everything is Illuminated: What Big Data Can Tell Us About Teacher Commentary. Assessing Writing, vol. 18, no. 4, 2013, pp. 241-256.

Dohrer, Gary. Do Teachers’ Comments on Students’ Papers Help? College Composition and Communication, vol. 39, no. 2, 1991, pp. 48-54.

Duncan, Neil. ‘Feedforward’: Improving Students’ Use of Tutors’ Comments. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 32, no 3, 2007, pp. 271-83.

Emmons, Kimberly. Rethinking Genres of Reflection: Student Portfolio Cover Letters and the Narrative of Progress. Composition Studies, vol. 31, no. 1, 2002, pp. 43-62.

Evans, Carol. Making Sense of Assessment Feedback in Higher Education. Review of Educational Research, vol. 83, no. 1, 2013, pp. 70-120.

Ferris, Dana R. Student Reactions to Teacher Response in Multiple-draft Composition Classes. TESOL Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 1, 1995, pp. 33-53.

Fishman, Jenn, and Mary Jo Reiff. Taking the High Road: Teaching for Transfer in a FYC Program. Composition Forum, vol. 18, 2008, https://compositionforum.com/issue/18/tennessee.php. Access 28 November 2021.

Formo, Dawn M., and Lynne M. Stallings. Where’s the Writer in Response Research? Examining the Role of Writer as Solicitor of Feedback in (Peer) Response. Peer Pressure, Peer Power: Theory and Practice in Peer Review and Response for the Writing Classroom, edited by Steven J. Corbett, Michelle LaFrance, and Teagan E. Decker, Fountainhead Press, 2014, pp. 43-60.

Frankenberg-Garcia, Ana. Providing Student Writers with Pre-Text Feedback. ELT Journal, vol. 53, no 2, 1999, pp. 100-106.

Freestone, Nicholas. Drafting and Acting on Feedback Supports Student Learning when Writing Essay Assignments. Advances in Physiology Education, vol. 33, 2009, pp. 98−102.

Henson, Roberta, and Sharon Stephenson. Writing Consultations Can Affect Quantifiable Change: One Institution’s Assessment. The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 33, 2009, pp. 1-5.

Hilgers, Thomas L., et al. The Case for Prompted Self-Assessment in the Writing Classroom. Self-Assessment and Development in Writing: A Collaborative Inquiry, edited by Jane Bowman Smith and Kathleen Blake Yancey, Hampton Press, 2000, pp. 1-24.

Hitt, Allison Harper. Rhetorics of Overcoming: Rewriting Narratives of Disability and Accessibility in Writing Studies. Conference on College Composition and Communication Studies in Writing and Rhetoric, 2021.

Hyland, Ken, and Fiona Hyland. State of the Art Article: Feedback on Second Language Students’ Writing. Language Teaching, vol. 39, 2006, pp. 83-101.

Inoue, Asao. Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. University Press of Colorado, 2019.

Inoue, Asao, and Tyler Richmond. Theorizing the Reflection Practices of Female Hmong College Students: Is Reflection a Racialized Discourse? A Rhetoric of Reflection, edited by Kathleen B. Yancey, Utah State UP, 2016, pp. 125-145.

Irons, Alastair. Enhancing Learning through Formative Assessment and Feedback. Routledge, 2008.

Jeffery, Francie, and Bonita Selting. Reading the Invisible Ink: Assessing the Responses of Non-Composition Faculty. Assessing Writing, vol. 6, no. 2, 1999, pp. 179-197.

Kerschbaum, Stephanie. Toward a New Rhetoric of Difference. NCTE, 2014.

Knoblauch, C.H., and Lil Brannon. Introduction: The Emperor (Still) has no Clothes: Revisiting the Myth of Improvement. Key Works on Teacher Response, edited by Richard Straub, Heinemann/Boynton-Cook, 2006, pp. 1-15.

Kryger, Kathleen, and Griffin X. Zimmerman. Neurodivergence and Intersectionality in Labor-Based Contracts. Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 13, number 2, 2020. https://journalofwritingassessment.org/article.php?article=156.

Lang, Susan. Evolution of Instructor Response? Analysis of Five Years of Feedback to Students. Journal of Writing Analytics, vol. 2, 2018, pp. 1-33.

Lee, Icy. Feedback in Writing: Issues and Challenges. Assessing Writing, vol. 19, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1-5.

Lipnevich, Anastasiya A., and Jeffrey K Smith. ‘I Really Need Feedback to Learn’: Students' Perspectives on the Effectiveness of the Differential Feedback Messages. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, vol. 21, 2009, pp. 347-367.

Lizzio, Alf, and Keithia Wilson. Feedback on Assessment: Student’s Perceptions of Quality and Effectiveness. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 33, no. 3, 2008, pp. 263-75.

Lundstrom, Kristi, and Wendy Baker. To Give is Better than to Receive: The Benefits of Peer Review to the Reviewer’s Own Writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 18, 2009, pp. 30-43.

Moore, Jessie L., and Randall Bass. Understanding Writing Transfer: Implications for Transformative Student Learning in Higher Education. Stylus Publishing, 2017.

Neal, Michael. The Perils of Standing Alone: Reflective Writing in Relation to Other Texts. A Rhetoric of Reflection, edited by Kathleen B. Yancey, Utah State UP, 2016, pp. 64-83.

Nicol, David, et al. Rethinking Feedback Practices in Higher Education: A Peer Review Perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 39, no 1, 2014, pp. 102-122.

Orrell, Janice. Feedback on Learning Achievement: Rhetoric and Reality. Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 11, no. 4, 2006, pp. 441-456.

Perkins, David, and Gavriel Salomon. Rocky Roads to Transfer: Rethinking Mechanisms of a Neglected Phenomenon. Educational Psychologist, vol. 24, no. 2, 1989, pp. 113-142.

Polio, Charlene. The Relevance of Second Language Acquisition Theory to the Written Error Correction Debate. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 21, 2012, pp. 375-389.

Pope, Nigel K.L. The Impact of Stress in Self and Peer Assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 30, no. 1, 2005, pp. 51-63.

Price, Margaret. Mad at School: Rhetorics of Mental Disability and Academic Life. University of Michigan Press, 2011.

Price, Margaret, et al. Feedback: All That Effort but What is the Effect? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 35, no. 3, 2010, pp. 277-89.

Richardson, Susan. Students’ Conditioned Response to Teachers’ Response: Portfolio Proponents, Take Note! Assessing Writing, vol. 7, no. 2, 2000, pp. 117-141.

Rust, Chris, et al. A Social Constructivist Assessment Process Model: How the Research Literature Shows Us This Could Be the Best Practice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 30, no. 3, 2005, pp. 231-40.

Rysdam, Sheri, and Lisa Johnson-Shull. Introducing Feedforward: Renaming and Reframing our Repertoire for Written Response. JAEPL, vol. 21, 2016, pp. 70-85.

Séror, Jérémie. Institutional Forces and L2 Writing Feedback in Higher Education. Canadian Modern Language Review, vol. 66, no. 2, 2009, pp. 203-232.

Stern, Lesa A., and Amanda Solomon. Effective Faculty Feedback: The Road Less Traveled. Assessing Writing, vol. 11, 2006, pp. 22-41.

Tao, Jian, et al. Ethics-related Practices in Internet-based Applied Linguistic Research. Applied Linguistics Review, vol. 8, no. 4, 2017, pp. 1-25.

Thorpe, Mary. Encouraging Students to Reflect as Part of the Assignment Process. Active Learning in Higher Education, vol. 1, no. 1, 2000, pp. 79-92.

Tiruchittampalam, Shanthi, et al. Measuring the Effectiveness of Writing Center Consultations on L2 Writers’ Essay Writing Skills. Languages, vol. 3, no. 4, 2018, https://www.mdpi.com/2226-471X/3/1/4.

Vardi, Iris. Effectively Feeding Forward from One Written Assignment Task to the Next. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 39, no. 5, 2012. pp. 599-610.

Walker, Mirabelle. Feedback and Feedforward: Student Responses and Their Implication. Reconceptualising Feedback in Higher Education: Developing Dialogue with Students, edited by Stephen Merry, Margaret Price, David Carless, and Maddalena Taras, Routledge, 2013, pp. 103-112.

Wardle, Elizabeth. ‘Mutt Genres’ and the Goal of FYC: Can we Help Students Write the Genres of the University? College Composition and Communication, vol. 60, no 4, 2009, pp. 765-789.

Warnsby, Anna, et al. Affective Language in Student Peer Reviews: Exploring Data from Three Institutional Contexts. Journal of Academic Writing, vol. 8, no. 1, 2018, pp. 28-53.

White, Edward M. The Scoring of Writing Portfolios: Phase 2. College Composition and Communication, vol. 56, no 4, 2005, pp. 581-600.

Williams, James, and David Kane. Assessment and Feedback: Institutional Experiences of Student Feedback: 1996 to 2007. Higher Education Quarterly, vol. 63, no. 3, 2009, pp. 264-286.

Wingate, Ursula. The Impact of Formative Feedback on the Development of Academic Writing. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 35, no. 5, 2010, pp. 519-33.

Wood, Shane. Engaging in Resistant Genres as Antiracist Teacher Response. The Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 13, no. 2, 2020. https://journalofwritingassessment.org/article.php?article=157.

Wood, Tara. Cripping Time in the College Composition Classroom. College Composition and Communication, vol. 69, no. 2, 2017, 260-286.

Wood, Tara, and Shannon Madden. Suggested Practices for Syllabus Accessibility Statements. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 18, no. 1, 2013. https://kairos.technorhetoric.net/praxis/tiki-index.php.

Yancey, Kathleen B. Reflection in the Writing Classroom. Utah State UP, 1998.

Yancey, Kathleen B., editor. A Rhetoric of Reflection. Utah State UP, 2016.

Yancey, Kathleen B., editor. Introduction: Contextualizing Reflection. A Rhetoric of Reflection. Utah State UP, 2016, pp. 3-20.

Yancey, Kathleen B. Getting Beyond Exhaustion: Reflection, Self-Assessment, and Learning. Clearing House, vol. 72, no. 1, 1998, pp. 13-17.

Yancey, Kathleen B., Matthew Davis, Liane Roberston, Kara Taczak, and Erin Workman. The Teaching for Transfer Curriculum: The Role of Concurrent Transfer and Inside- and Outside-School Contexts in Supporting Students’ Writing Development. College Composition and Communication, vol. 71, no. 2, 2019, pp. 268-295.

Yancey, Kathleen B., et al. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State University Press, 2014.

Young, Beth R., and Barbara A. Fritzsche. Writing Center Users Procrastinate Less: The Relationship between Individual Differences in Procrastination, Peer Feedback, and Student Writing Success. The Writing Center Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, 2002, pp. 45-58.

Ziegler, Nicholas A., and Aleidine J. Moeller. Increasing Self-Regulated Learning through the LinguaFolio. Foreign Language Annals, vol. 45, no. 3, 2012, 330-348.

Responding for Transfer from Composition Forum 50 (Fall 2022)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/50/responding-transfer.php

© Copyright 2022 Dan Melzer.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 50 table of contents.