Composition Forum 50, Fall 2022

http://compositionforum.com/issue/50/

Mindful Practice & Metacognitive Awareness in the Writing Class: A Quantitative Pilot Research Study

Abstract: Over the past two decades, writing studies scholars have continually stressed the importance of fostering the development of student metacognition in the writing classroom. Not only does the development of a metacognitive awareness of the writing process help students to become stronger writers, it also allows them to more successfully transfer the knowledge they gain in their writing classes to other contexts. Although scholars have suggested a variety of reflective activities and assignments intended to encourage the development of metacognition, none have explicitly explored the potential links between mindfulness practice and metacognitive awareness. Mindfulness based pedagogies are increasingly finding their way into K-12 and college classrooms because of their ability to help students improve their memory, attention, and emotional regulation. This pilot study investigates whether or not mindfulness interventions in a college writing class can also help students develop metacognition. More specifically, this pilot study consisted of a control group and a treatment group of students, both enrolled in a foundational writing course. While both groups were asked to take the Metacognitive Writing Awareness Inventory at the beginning and the end of the course, only the treatment group participated in weekly mindfulness activities. Results from this pilot study support the hypothesis that mindfulness interventions can help to foster the development of writer metacognition in the college writing classroom.

Over the past two decades, educators have begun to realize and theorize the important role played by metacognition (simply defined as an awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes) in the learning process. The development of learner metacognition—many of these educators suggest—enables students to become more reflective, motivated and self-regulated learners. More recently, writing studies scholars have begun to identify links between the development of metacognition in the writing class, and the subsequent “transfer” of writing skills to other contexts (Nowacek; Driscoll and Wells; Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts; Driscoll and Powell; Gorzelsky et al., Cultivating Constructive Metacognition; Moore and Bass). As the transfer of writing knowledge gained in first-year composition (FYC) courses to courses within the disciplines is a point of constant concern, debate, and research to writing studies scholars, the association of metacognition with transfer has greatly increased the interest in facilitating metacognition in the writing class. Indeed, the term “Teach for Transfer” (Yancey et al., Writing Across Contexts) has become synonymous with the idea that a strong metacognitive awareness of their writing process can help students transfer their writing knowledge.

Convinced of the importance of metacognition, many writing instructors and researchers have begun to suggest the implementation of certain reflective activities and assignments intended to help foster the development of metacognition among students. For example, Kathleen Yancey and her colleagues (Writing Across Contexts; A Rhetoric of Reflection; Reflection in the Writing Class; “Writing Across College”) have often credited reflection and a variety of reflective writing assignments with being responsible for the development of learner-metacognition. Doug Downs and Elizabeth Wardle suggest that making the threshold concepts of writing explicit for students will help them become more metacognitively aware of their writing. Rebecca Nowacek advises writing instructors to facilitate transfer by helping their students develop a meta-awareness of genre and rhetorical knowledge. More recently, Mika LaVaque-Manty and E. Margaret Evans and, separately, E. Ashley Hall at al. propose that students engage in continual planning, monitoring, and evaluation activities to help make the value of these metacognitive concepts explicit to them. As a relatively new area of investigation, researchers are continually adding to the conversation about how to best facilitate metacognition. In short, current conversations on reflection, metacognition, and transfer make it evident that, as a field, we are very much still in the process of discovering how to best implement reflective activities in the writing class that will generate metacognitive awareness.

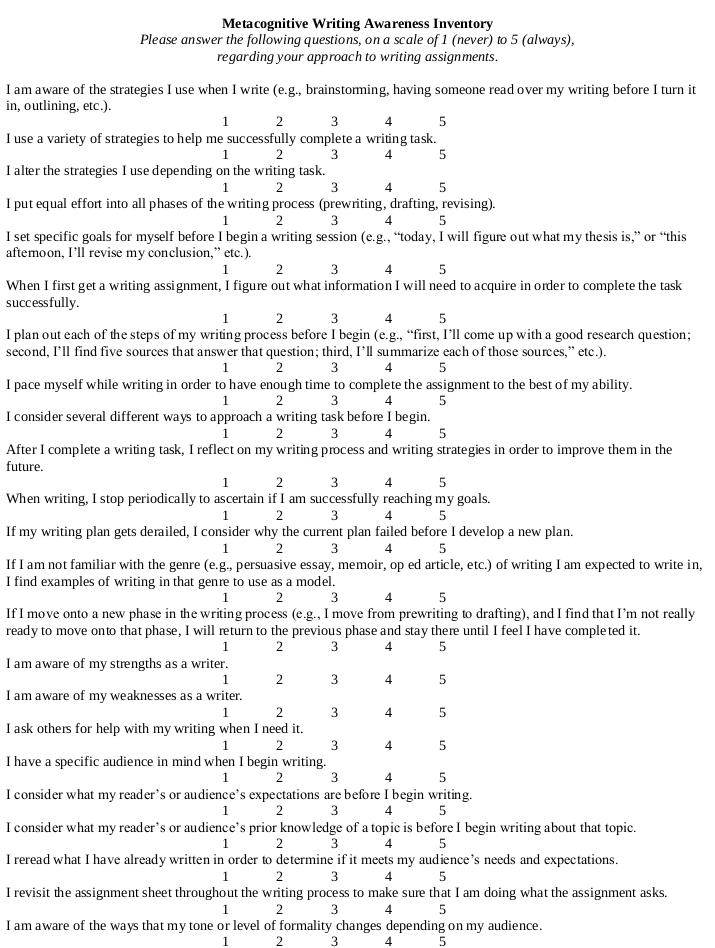

As I have previously suggested, one way that writing instructors may be able to encourage reflection, and thereby the development of metacognition in students, is by implementing mindful and contemplative activities—such as mindfulness meditation, breathing exercises, reflective journaling, yoga, walking meditation, visualization, mindful listening, mindful dialogue, and storytelling—in their courses (Chaterdon). As a long-time practitioner of mindful and contemplative teaching methods, I have seen first-hand the positive impact that these methods can have on a students’ ability to introspect and reflect. In order to test this hypothesis, I designed and conducted a pilot research study during the 2019 spring semester at my college, which attempted to assess the effects of mindfulness interventions in a writing course on the development of student metacognition. Although this was a preliminary study—with a sample size too small to be statistically significant—I designed this study following a standard quantitative research format, in the hopes that the design would make it easier to replicate the study in the future. As such, I utilized a “treatment group” (who participated in the mindfulness interventions) and a “control group” (who did not participate in the mindfulness interventions) to determine what effect, if any, the interventions had. I assessed the effectiveness of the implementations through a “Metacognitive Writing Awareness Inventory” (MWAI) (see Figure 1), which I developed for this pilot study and administered at the beginning and end of the course, in both sections. By comparing both groups’ responses to the MWAI, I was able to identify some interesting trends in the metacognitive development of each group.

Although both the control group and the treatment group reported a greater metacognitive awareness of their writing process, of the writing strategies they use, and of genre and audience by the end of the semester, the treatment group appeared to experience a more dramatic change in their metacognitive awareness of these concepts, implying that implementing mindfulness activities into a writing course may have an additive effect on the development of student metacognition. Although the sample size of this study was small, and the findings are preliminary, this research project poses some important questions for the field of writing studies to consider, primarily: how can we best encourage the development of a meaningful and disciplined approach to reflection and introspection (as opposed to the “afterthought” it can become when included only as an addendum assignment to other assignments) so that students’ metacognitive awareness of their writing is expanded at a fundamental and lasting level? In what follows, I discuss recent research on the links between the emotional and cognitive domains of knowledge transfer, the connections between this research and the research on mindfulness in higher education, as well as the findings of this pilot study and its implications for classroom practice and future research.

DISPOSITIONS, EMOTIONS, & HABITS OF MIND: RECENT TRENDS IN RESEARCH ON METACOGNITION & TRANSFER

As Ellen Carillo notes, the recent focus on metacognition in research on transfer, is only the newest phase in the development of transfer research, “after decades of privileging sociocultural approaches to understanding and teaching writing, the last few years have seen an increase in the number of studies that explore how individuals’ dispositions affect the transfer of writing knowledge” (40). This is not to say that the sociocultural has no impact on transfer—because it clearly does—only that the field may have (until recently) inadvertently overlooked the ways that “individuals’ dispositions affect the transfer of writing knowledge” and the development of metacognitive awareness. In this section, I will illustrate how this recent interest in the emotional components of metacognition may shed some light on the inherent potential of a mindfulness-based approach to writing instruction to facilitate metacognition and transfer. Particularly germane to this pilot study is the scholarship that has surfaced on 1) the relationship between students’ dispositions, emotions, and habits of mind to the successful development of metacognition and transfer; and 2) the capability of contemplative and mindful pedagogies to simultaneously facilitate students’ cognition and their emotional resilience.

Over the past two decades, scholars in writing studies have become very interested in the role that student dispositions, emotions, and habits of mind—which sometimes includes metacognition—play in the successful transfer of knowledge. Elizabeth Wardle (Understanding ‘Transfer’ from FYC) conducted one of the first studies to explore student dispositions, and found that a failure to transfer writing skills from a FYC course to disciplinary courses might have more to do with a lack of student motivation than a lack of intellectual capability. Wardle (Creative Repurposing) also discovered that transfer is very much influenced by whether or not a student possesses a “problem-exploring” (i.e., curious and reflective) or an “answer-getting” disposition. Likewise, Dana Driscoll notes that students’ expectations about and perceptions of the transferability of an FYC course greatly impact their ability to successfully transfer knowledge. Furthermore, Driscoll and Jennifer Wells discovered that student dispositions, as opposed to their intellectual traits, played a large role in the ability of students to transfer their knowledge to new contexts. The four student dispositions that Driscoll and Wells found to be most significant in enabling or inhibiting transfer were “value, self-efficacy, attribution, and self-regulation” (n.p.). Much of this research on dispositions and transfer was informed by, or overlapped with, the creation of the “habits of mind” in the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing, created by the National Council of Teachers of English, the Council of Writing Program Administrators, and the National Writing Project. The Framework lists the eight habits of mind, which are “essential for success in college writing,” as: curiosity, openness, engagement, creativity, persistence, responsibility, flexibility, and metacognition (n.p.). In general, research on student dispositions—supported by the Framework and “habits of mind”—suggest that transfer of writing knowledge is just as much impacted by students’ perceptions, values, beliefs, and emotions as it is by students’ intellectual capacity.

In addition to researching why student dispositions play a role in the successful transfer of knowledge, many scholars have also suggested a variety of practices—which often incorporate a focus on metacognition—geared toward this outcome. For example, Driscoll and Roger Powell suggest that instructors can facilitate positive emotions in the writing class—and thereby transfer—by explicitly teaching students the concepts of metacognitive monitoring and control, regarding their emotional dispositions. Similarly, Brian Jackson has argued that teachers should enable students by helping them develop a more intentional, self-directed approach to writing. In general, many of the scholars who write about transfer and metacognition (Yancey; Driscoll; Wardle; Nowacek) encourage instructors to include activities in their courses that ask students to engage in various kinds of metadiscourse: keeping a writing process journal, analyzing one’s genre and audience before beginning to write, engaging in peer review, writing reflections on one’s writing process, and having explicit discussions about threshold concepts or writing strategies.

These practices, although entirely useful and necessary to the development of metacognition, still draw a distinction between “cognitive” and “emotional” in a way that may not wholly serve writing instructors or students. Despite acknowledging the connection between dispositions, emotions, and metacognition, our field seems to struggle with how to meaningfully coalign these concepts. As E. Shelley Reid recently noted:

Placing “disposition” into a larger conversation about “cognition” in composition studies is challenging. If we use one common distinction, dispositional attributes might be seen as oppositional to cognitive achievements, in the way that “affective” and “intellectual” achievements are often separated . . . yet perhaps disposition and cognition have some elements in common. (292)

Likewise, in their recent article on neuroplasticity and writing instruction, Gwen Gorzelsky et al. suggest that writing instructors should consider cognition not from the traditional Cartesian, mind-body split perspective, but from a “situated” perspective, which posits “that cognition is fundamentally shaped by bodily experience (as distinct from strictly mental experience) and by emotional, socio-cultural, physical, and other environmental factors” (Meaningful Practice 119). A number of scholars in education and educational psychology (Haskell; Costa and O’Leary; Newbury et al.) concur that learning and transfer of knowledge happens somewhere in the space between the emotional, intellectual, and social. Increasingly, scholars from a variety of fields agree that conceiving of learning as strictly cognitive or intellectual is not only incorrect, it also does a disservice to our students. When we ignore (inadvertently or otherwise) the emotional, socio-cultural, and physical factors at play in the learning process, we disadvantage students by not helping them to develop the full range of skills that allow them to be successful learners and to achieve transfer of knowledge.

CONTEMPLATIVE PEDAGOGICAL APPROACHES & MINDFULNESS IN THE WRITING CLASS

One pedagogical approach that embraces the idea that higher education is a social, emotional, and cognitive endeavor is the field of contemplative pedagogy, sometimes referred to as mindfulness in education. The inclusion of contemplative and mindful approaches in higher education is a relatively new phenomenon. One of the earliest venturers into this pedagogical territory was Parker Palmer who argued that a more holistic and mindful approach to education can better serve both students and teachers. Since the late 90’s, a number of books and articles have been published that explain what a contemplative or mindful pedagogy is, how to enact these pedagogical approaches, and what the effects of these approaches are. Daniel Barbezat and Mirabai Bush for instance, list the objectives of contemplative pedagogy as:

1. Focus and attention building, mainly through focusing meditation exercises that support mental stability. 2. Contemplation and introspection into the content of the course, in which students discover the material in themselves and thus deepen their understanding of the material. 3. Compassion, connection to others, and a deepening sense of the moral and spiritual aspect of education. 4. Inquiry into the nature of their minds, personal meaning, creativity and insight. (11)

Similarly, Tobin Hart explains that “The contemplative mind is opened and activated through a wide range of approaches—from pondering to poetry to meditation—that are designed to quiet and shift the habitual chatter of the mind to cultivate a capacity for deepened awareness, concentration, and insight” (“Opening the Contemplative Mind” 29). Much of the growing support for contemplative approaches in the classroom are a result of research conducted by scholars in educational psychology and cognitive science, whose findings indicate the effectiveness of these approaches. In particular, recent scholarship supports the idea that helping students to reflect and introspect—by way of mindful or contemplative practice—can facilitate students’ capacity for emotional regulation, attention, memory, and executive functioning (Hart, “Interiority and Education”; Roeser and Peck; Zajonc; Norris et al.; Zhang et al.). By focusing not only on the cognitive aspects of education, but also on the social and emotional, contemplative and mindful pedagogues aim to educate the “whole” person.

Since the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s—during the expressive movement within the field of writing and composition studies—a number of writing scholars and pedagogues experimented with implementing mindful or contemplative practices (although, not always called such) in the writing classroom. James Moffett, for example, suggested that teachers lead students through guided meditations as a way of helping them tap into stream-of-consciousness thoughts in order to capture them on the page. Similarly, Regina Foehr and Susan Schiller, Mary O’Reilley, and Sondra Perl all provide teachers with contemplative and mindful writing approaches and activities intended to help students more authentically engage with their own thinking and learning. Some of these practices include mindfulness meditation, breath awareness, the use of Zen koans, intentional silence, and deep listening. More recently, Christy Wenger in Yoga Minds, Writing Bodies has suggested teachers adopt a yogic mindset in the writing class, and encourages the use of “body blogs” assignments, which give students the space to “consider how their bodies [are] implicated in their writing and learning processes” (61). Likewise, Alexandria Peary in Prolific Moment argues that we should incorporate an approach to writing instruction that “highlights present temporality in every writing occasion and at every phase” instead of focusing exclusively on rhetorical situation or the writing process (1). To this end, she suggests that instructors pair breathing exercises or meditations with low-stake writing assignments to keep students connected to their writing, themselves, and the present moment.

Whether they practice mindful journaling, meditation, deep listening, breathwork, yoga or any other mindfulness practice, writing scholars and pedagogues who argue for the adoption of a mindful or contemplative pedagogical approach often do so because they have seen, firsthand, the benefits such an approach offers their students and themselves. Mainly, these benefits are a greater capacity to focus awareness, to be present—physically, mentally, and emotionally—to whatever is currently happening in the classroom and in one’s personal life, to engage in introspection, and to reflect meaningfully. However, very few of these scholars have researched or discussed the ways that a mindful pedagogical approach is or can be linked to metacognition (despite what this author sees as a potentially important link between the two). The pilot study discussed in this article responds to the need for additional research on the possible connections between metacognition and mindfulness. In particular, this study explores the potential benefits of infusing our field’s current practices—designed to encourage metacognition—with a mindful or contemplative pedagogical approach. By doing so, we may be able to better support the cognitive and emotional elements necessary for the development of metacognition.

METHODS

Site and Context

In order to assess how mindfulness implementations might affect the development of metacognitive awareness among writing students, I conducted a pilot study with two sections of an introduction to writing studies course called “Writing as a Discipline” at Marist College, in the spring of 2019. Marist College is a private, four-year, comprehensive liberal arts college located in upstate New York. Writing as a Discipline is a required, foundational course for English majors, but non-majors sometimes take this course for elective credit. Typically, this course is populated by first-year students and sophomores, but there are usually a handful of upper-division students in the class as well. The textbook I use for this course is Elizabeth Wardle and Doug Downs’ Writing About Writing, which teaches students about the threshold concepts of writing, and encourages students to think about writing not just as something we do, but as something we can study and analyze. I break this course up into four units, and each unit poses a new question to the students about writing: “how do we learn to write?; what does writing do?; how is writing taught?; and how are writing and technology interconnected?” By focusing on the threshold concepts of writing and approaching writing as a topic of study, I encourage students to consider the thinking behind their writing processes. In other words, I encourage them to develop a metacognitive awareness of their writing.

While both of the sections of Writing as a Discipline that participated in this study had identical syllabi, activities, and assignments, only one of the sections took part in the mindfulness implementations. In this way, I attempted to create a control group and a treatment group in this pilot study. Although this course—in general—is designed to foster the development of a metacognitive awareness about one’s writing process, I wanted to determine if the implementation of mindfulness activities in a writing studies course could help to further promote the development of metacognitive awareness. To answer this research question, I implemented weekly mindfulness sessions in the treatment group section that I called “Mindfulness Mondays.” Each Monday, I introduced students to a new, brief mindfulness activity at the beginning of class. These mindfulness implementations included a variety of mindfulness meditations (e.g., body scan meditations, guided visualizations, mindful drawing, mindful listening, yoga, and breathing exercises) and usually lasted between ten and fifteen minutes. I chose to use a variety of practices—as opposed to one practice throughout the semester—for a few different reasons. First, given that many of the students were unfamiliar with mindfulness and did not have an established mindfulness practice prior to this course, I wanted to introduce the students to a range of practices so that they could experiment and, hopefully, find the practice(s) that suited them the best. Second, I was aware that asking the students to take part in the same mindfulness activity, every Monday, throughout the entire course, would probably become monotonous. Because one of my goals for this course was to encourage students to adopt a mindful discipline, and incorporate this discipline into all areas of their life, I didn’t want to turn them off of mindfulness or have them associate mindfulness with (what might become) a boring and tedious weekly mindfulness meditation. Finally, although the practices differed from week to week, they each had the same goal of fostering a present-moment awareness. It was the development of this awareness—not a particular practice or technique—that I emphasized with the students. However, my choice to include a variety of practices makes a true replication of this study difficult to perform. Therefore, one of the future research goals for this project is to determine a way to isolate and study the effects of one particular mindfulness practice at a time.

I assessed the impact of the implementations through a “Metacognitive Writing Awareness Inventory,” which I administered at the beginning and end of the course, in both sections. By comparing the test and control groups’ beginning-of-the-semester and end-of-the-semester responses to the Metacognitive Writing Awareness Inventory (MWAI), I hoped to determine if the mindfulness implementations had any effect on the metacognitive development of the treatment group, in comparison to the control group.

Participants

The two sections of Writing as a Discipline that participated in this study were both in-person courses, taught during the same sixteen-week semester. Both sections met twice weekly for seventy-five minutes each class, but the sections did not meet on the same days or at the same times. Seventeen students were enrolled in both the control group section and the treatment group section. Table 1 shows the breakdown of the students by sex, race, year of study, and major. Both sections were predominated by students identifying as white, female English majors in their sophomore year.

Table 1. Demographics of Participants in the Pilot Study.

|

Characteristics |

Control Group |

Treatment group |

|---|---|---|

|

Students identifying as female |

10 |

12 |

|

Students identifying as male |

7 |

5 |

|

Students identifying as white |

15 |

12 |

|

Students identifying as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and/or Persons of Color) |

2 |

5 |

|

First-Year |

2 |

5 |

|

Sophomore |

10 |

9 |

|

Junior |

3 |

3 |

|

Senior |

2 |

0 |

|

English Majors |

14 |

13 |

|

Business Majors |

1 |

1 |

|

Communications Majors |

1 |

1 |

|

Fashion Merchandising Majors |

0 |

1 |

|

Undecided |

1 |

1 |

As the principle investigator, I chose one section to be the control group and one to be the treatment group, but the selection process was completely random. I determined the treatment and control groups before the semester began, before I had met any of the students, and before I viewed the roster. The students were informed about the purpose of the study, but were not told that engaging in mindfulness activities will necessarily lead to the development of a greater metacognitive awareness of one’s writing. Completion of the MWAI was completely voluntary for all of the students.

Data Collection and Instruments

The primary instrument used in this pilot study was the Metacognitive Writing Awareness Inventory (MWAI), which I developed specifically for this study. I decided to use an inventory to collect data, as opposed to only relying on students’ written responses, because so much of the field’s current research on mindfulness in the writing class is qualitative or anecdotal. The field needs more diversified research methods on this topic to enrich our understanding of how mindfulness impacts the development of metacognition. A number of scholars within writing studies have heralded this call for methodological pluralism in the field (Johanek; Haswell). Therefore, this pilot study represents a foray into the less-charted territory of quantitative studies on mindfulness and metacognition with the hope that, as this study becomes replicated and the findings corroborated, the field will be provided with a more diverse source of data from which to inform pedagogy and theory.

I had to develop my own instrument for this pilot study because (at the time of this study) no published metacognitive awareness inventory, specific to writing, existed. I modeled the inventory after Gregory Schraw and Rayne Sperling Dennison’s metacognitive awareness inventory, which used a Likert scale to assess metacognitive awareness in learning, more generally (see Appendix). Charles MacArthur et al. published a questionnaire specific to writing in 2016, except that this questionnaire was intended to assess only motivation for writing via four scales: “Self-Efficacy for Writing, Achievement Goal Orientation for Writing, Beliefs About Writing, and Affect Toward Writing” (35). Each of the twenty-three questions on the MWAI, on the other hand, asked students to reflect on their awareness of their approach to writing and writing tasks. I asked students to record their responses to the inventory questions using a five-point Likert Scale, with a 1 indicating something the students never do or think about and a 5 indicating something students always do or think about (see Figure 1). The MWAI was administered to students via Google Forms and the responses were not anonymous so that I could track individual students’ metacognitive development over the course of the semester.

Data Analysis

Before analyzing the students’ responses to the MWAI, I first grouped the questions into one of these four categories: awareness of writing strategies, awareness of writing process, awareness of genre and audience, and awareness of writing competency. These categories were derived from the current theory and research within writing studies, which holds that we can help our students develop metacognition if we encourage them to consider their audience and genre, as well as their writing processes and strategies (Yancey et al. “Writing Across College,” Writing Across Contexts; Nowacek; Driscoll; Wardle, etc.). Informed by this research, the course was designed to continually reinforce these concepts. By designing the MWAI to collect data on these categories, I hoped to measure (as accurately as possible) how metacognitively aware—about their writing—each student was at the beginning and end of the course. Table 2 shows which of the questions I placed into each category. Because the sample size of this pilot study was so small, and because the instrument had not been tested previously, the results of this study are preliminary and only intended to indicate potential trends and illuminate areas for future research.

Table 2. Question Categories for the Metacognitive Writing Awareness Inventory.

|

Category |

Questions |

|---|---|

|

Awareness of Writing Strategies |

I am aware of the strategies I use when I write (e.g., brainstorming, having someone read over my writing before I turn it in, outlining, etc.). I use a variety of strategies to help me successfully complete a writing task.

I alter the strategies I use depending on the writing task. I ask others for help with my writing when I need it. |

|

Awareness of Writing Process |

I put equal effort into all phases of the writing process (prewriting, drafting, revising). I set specific goals for myself before I begin a writing session (e.g., “today, I will figure out what my thesis is,” or “this afternoon, I’ll revise my conclusion,” etc.). When I first get a writing assignment, I figure out what information I will need to acquire in order to complete the task successfully. I plan out each of the steps of my writing process before I begin (e.g., “first, I’ll come up with a good research question; second, I’ll find five sources that answer that question; third, I’ll summarize each of those sources,” etc.). I pace myself while writing in order to have enough time to complete the assignment to the best of my ability. I consider several different ways to approach a writing task before I begin. After I complete a writing task, I reflect on my writing process and writing strategies in order to improve them in the future. When writing, I stop periodically to ascertain if I am successfully reaching my goals. If my writing plan gets derailed, I consider why the current plan failed before I develop a new plan. If I move onto a new phase in the writing process (e.g., I move from prewriting to drafting), and I find that I’m not really ready to move onto that phase, I will return to the previous phase and stay there until I feel I have completed it |

|

Awareness of Genre and Audience |

If I am not familiar with the genre (e.g., persuasive essay, memoir, op ed article, etc.) of writing I am expected to write in, I find examples of writing in that genre to use as a model. I have a specific audience in mind when I begin writing. I consider what my reader’s or audience’s expectations are before I begin writing. I consider what my reader’s or audience’s prior knowledge of a topic is before I begin writing about that topic. I reread what I have already written in order to determine if it meets my audience’s needs and expectations. I revisit the assignment sheet throughout the writing process to make sure that I am doing what the assignment asks. I am aware of the ways that my tone or level of formality changes depending on my audience. |

|

Awareness of Writing Competency |

I am aware of my strengths as a writer. I am aware of my weaknesses as a writer. |

RESULTS

The following graphs report the averages for the pre- and posttest responses to the MWAI, broken down by category. Response rates were similar for the pre- and posttest, although there was a little bit of attrition at the end of the semester. Of the seventeen students in each section, fifteen completed the MWAI at the beginning of the semester in the control section, and sixteen completed it from the treatment section. At the end of the semester, thirteen of them completed the MWAI in the control section and sixteen in the treatment section. In total, I received thirty-one responses to the MWAI at the beginning of the semester, and twenty-nine responses to the MWAI at the end of the semester.

In general, the responses to the MWAI seem to indicate the emergence of a pattern that includes three main elements. The first is that all of the students, in both the control and treatment groups, indicated an increase in metacognitive awareness by the end of the semester. Second, the treatment groups’ pretest scores were almost always lower than the control groups’ pretest scores; in other words, the treatment group reported less metacognitive awareness than the control group at the start of the semester. Finally, the treatment group’s posttest scores often indicated that the treatment group experienced a slightly larger change in their metacognitive awareness—over the course of the semester—than the control group.

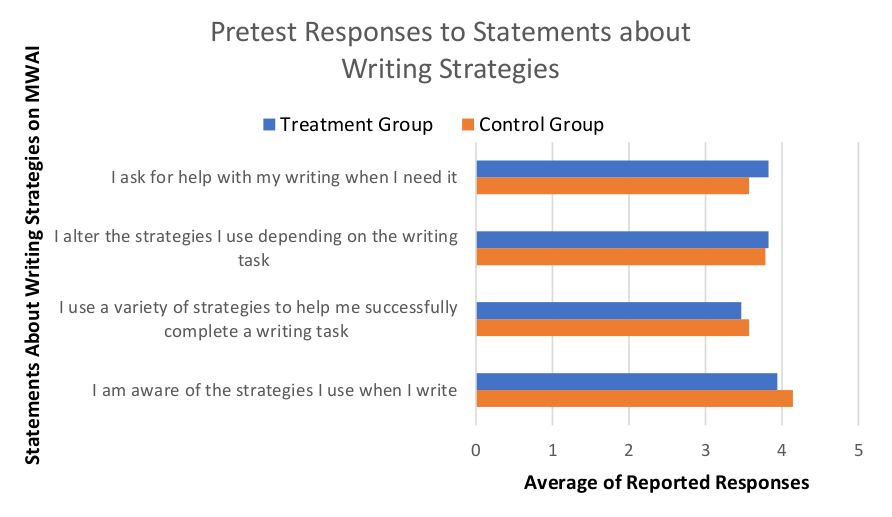

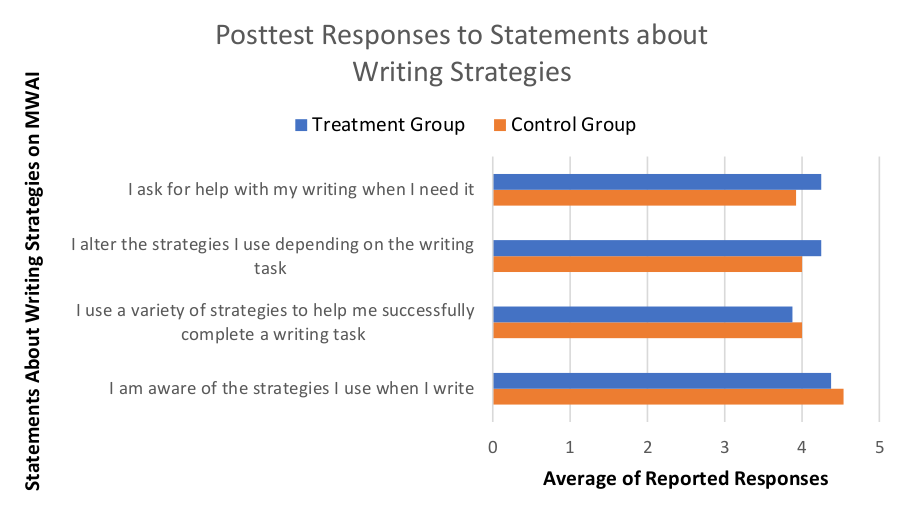

The first set of questions on the MWAI attempted to ascertain whether the students were aware of the strategies they use when engaged in a writing task. Figures 2 and 3 compare students’ pretest and posttest scores regarding statements about awareness of writing strategies, respectively. Unlike with the other data sets, the treatment and control groups report about the same level of metacognitive awareness at the beginning of the semester. Similar to the other data sets, though, both groups reported an increase in their metacognitive awareness by the end of the semester.

Figure 2. Pretest Responses for both the Control and Treatment Group to Statements about Awareness of Writing Strategies

Figure 3. Posttest Responses for both the Control and Treatment Group to Statements about Awareness of Writing Strategies

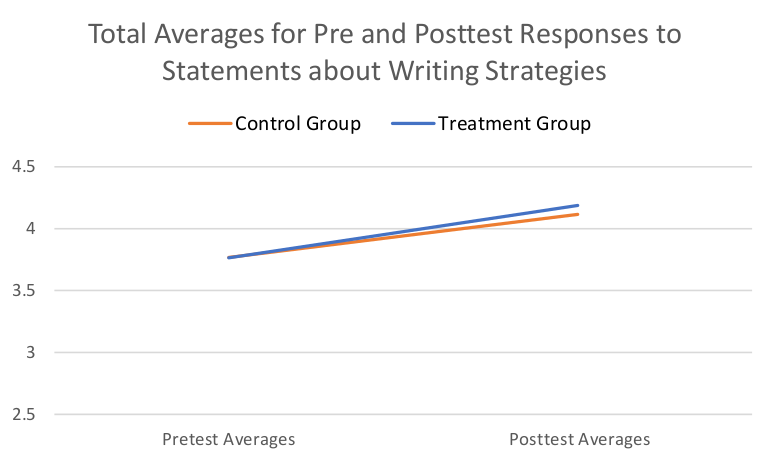

Figure 4 compares the average scores for both the pretest and the posttest statements about awareness of writing strategies, and indicates a slightly more pronounced increase in metacognitive awareness of the treatment group by the time of the posttest.

Figure 4. Total Averages for Pre and Posttest Responses to Statements about Writing Strategies for both the Control and Treatment Group

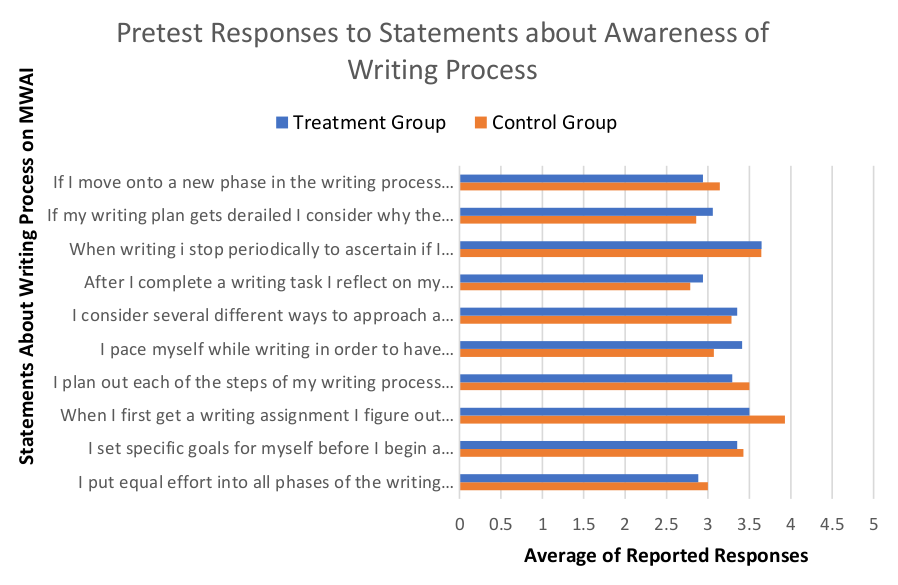

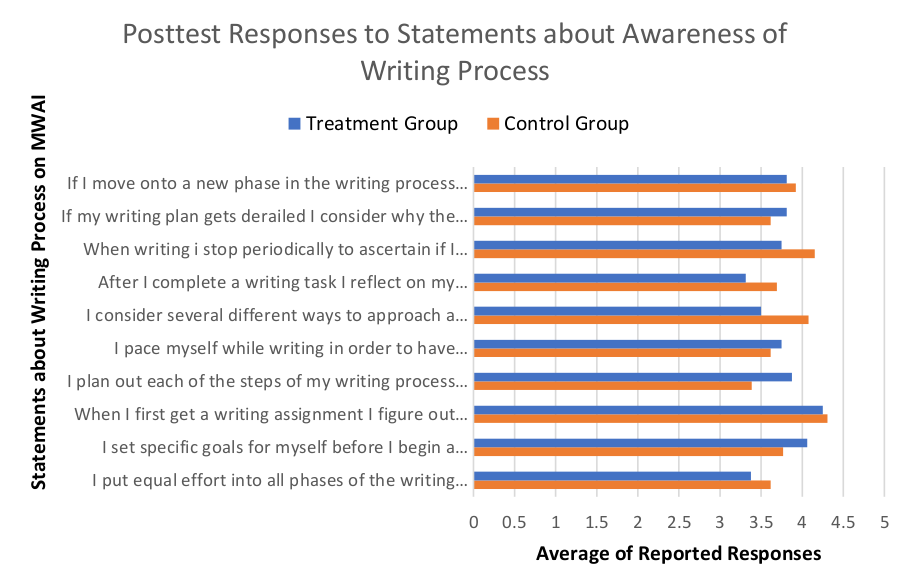

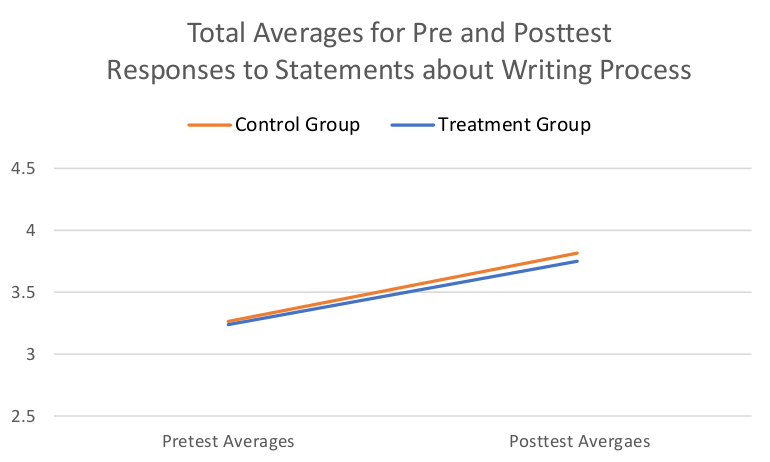

The second set of questions on the MWAI attempt to determine how aware the students are of their writing process. Figures 5 and 6 compare students’ pretest and posttest scores regarding statements about awareness of writing process, respectively. As indicated by the students’ responses, the control group possessed a slightly greater metacognitive awareness of their writing process at the time of the pretest than the treatment group. At the time of the posttest, both groups reported an increased metacognitive awareness of their writing process.

Figure 5. Pretest Responses for both the Control and Treatment Group to Statements about Awareness of Writing Process

Figure 6. Posttest Responses for both the Control and Treatment Group to Statements about Awareness of Writing Process

Figure 7 compares the average scores for both the pretest and the posttest statements about writing process. As discussed above, the reported responses indicate that both the control group and the treatment group experienced a greater metacognitive awareness of writing process by the end of the semester, and this graph indicates that this increase happened at mostly similar rates.

Figure 7. Total Averages for Pre and Posttest Responses to Statements about Writing Process for both the Control and Treatment Group

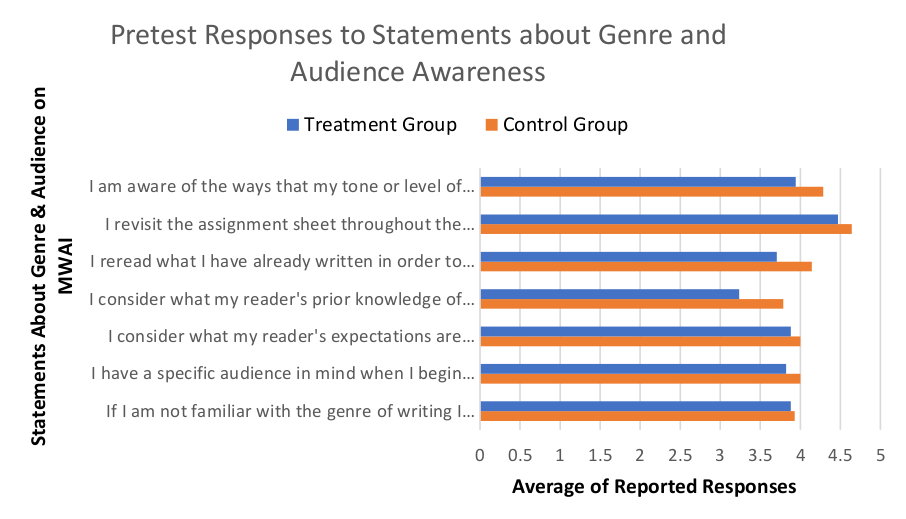

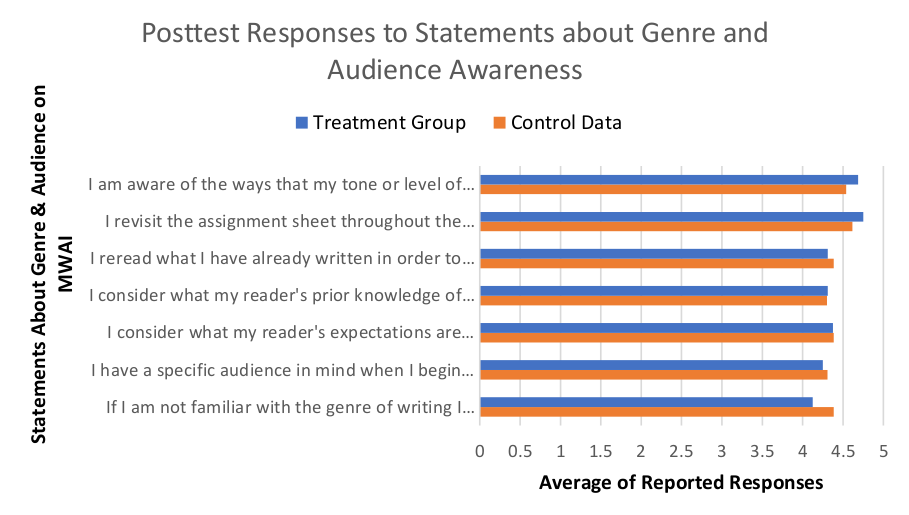

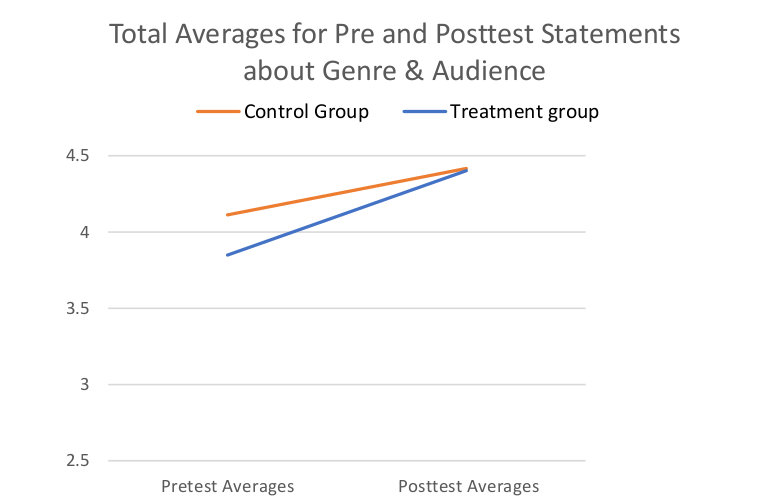

The next set of questions on the MWAI ask students about their awareness of genre and audience when they write. Figures 8 and 9 compare students’ pretest and posttest scores, respectively. As with the responses to the statements about writing process, the pretest responses to the statements about genre and audience indicate that the treatment group experienced less metacognitive awareness of genre and audience than the control group, at the beginning of the semester. Furthermore, both groups reported an increase in metacognitive awareness by the end of the semester.

Figure 8. Pretest Responses for both the Control and Treatment Group to Statements about Awareness of Genre and Audience

Figure 9. Posttest Responses for both the Control and Treatment Groups to Statements about Awareness of Genre and Audience

Figure 10 compares the average scores for both the pretest and the posttest statements about genre and audience. It appears that, by the end of the semester, both groups achieved about the same level of awareness of genre and audience. However, what is unique about this data set is that the treatment group’s responses indicate a greater increase in metacognitive awareness of genre and audience than the control group. Although the treatment group reported less metacognitive awareness than the control group at the pretest, by the posttest, they appear to have “caught up” to the control group.

Figure 10. Total Averages for Pre and Posttest Responses to Statements about Genre & Audience for both the Control and Treatment Group

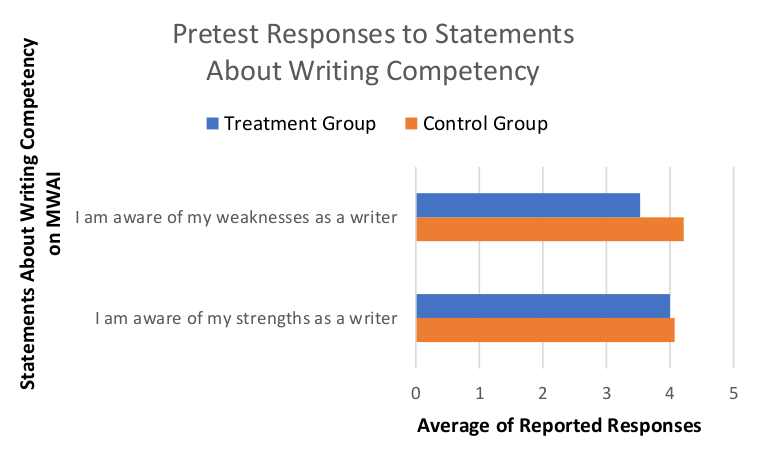

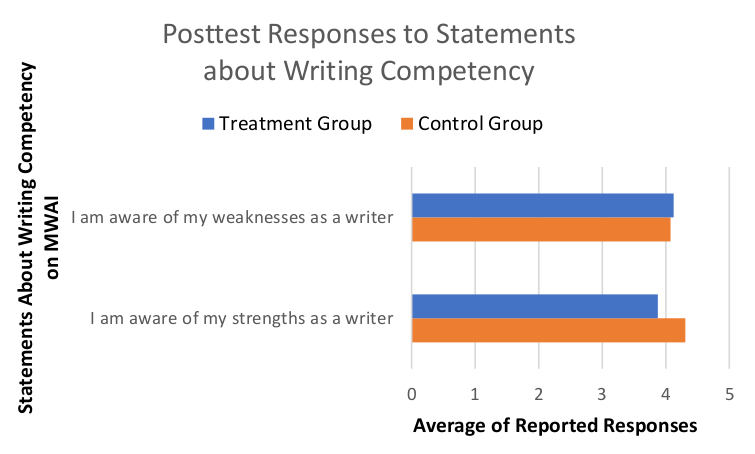

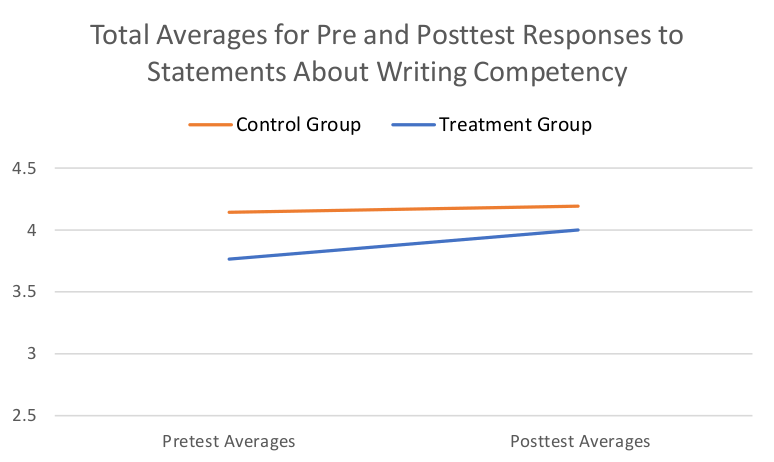

The last set of questions deals with how aware the students are of their weaknesses and strengths as writers. Figures 11 and 12 compare students’ pretest and posttest scores, respectively. Similar to the data sets on genre and audience and writing process, the control group reported a greater metacognitive awareness at the time of pretest. Also similar to all of the previous data sets, both groups reported an increase in metacognitive awareness over the course of the semester.

Figure 11. Pretest Responses for both the Control and Treatment Group to Statements about Awareness of Writing Competency

Figure 12. Posttest Responses for both the Control and Treatment Group to Statements about Awareness of Writing Competency

Figure 13 compares the average scores for both the pretest and the posttest statements about awareness of writing strategies. What is interesting about these averages is that the control group only reported a very slight increase in metacognitive awareness over the course of the semester, while the treatment groups’ reported change was—relatively speaking—more pronounced.

Figure 13. Total Averages for Pre and Posttest Responses to Statements about Writing Competency for both the Control and Treatment Group

DISCUSSION

The results of this pilot study indicate that all of the students, in both the control and treatment groups, experienced an increase in metacognitive awareness over the course of the semester. According to their responses to the MWAI, most of the students experienced the greatest change in awareness regarding “writing process” and “genre and audience.” This is probably a result of these two concepts being more consistently discussed during the course of the semester than writing strategies and competency. It is important to note that an increase in metacognitive awareness of writing and writing process are always one of the primary goals of this course (during any semester I have taught it); and to that end, this course was successful. The more interesting revelation of this data, though, is that for three of the four data sets—writing strategies, genre and audience, and writing competency—it appears that the treatment group experienced a slightly higher rate of increase in their metacognitive awareness than the control group. Again, it bears repeating that this increase was only slight, and that this data (due to its small sample size) is not statistically significant; nonetheless, I think it reveals some interesting trends, worthy of additional research. These trends imply that implementing mindfulness activities into a writing course may have an additive effect on the development of student metacognition.

In addition to the small sample size of this pilot study, there are a number of other limitations to this study’s design. The largest of these is that the reliability of the MWAI was never thoroughly tested. Future research should prioritize the testing of the instrument to ensure reliability. Another limitation of this study is that the sample size was not only small, but also composed primarily of white, middle and upper class students. Future replications of this study should aim to include a larger and more diverse sample so as not to perpetuate “white habitus” in research on writing studies. Furthermore, self-reported measures of metacognitive awareness may not accurately represent changes in awareness over the course of the semester. Although outside of the scope of this present study, future replications should aim to collect both quantitative and qualitative data in order to provide a counterpoint to the self-reported measures of the MWAI, and to provide our field with a wider variety of data to inform our pedagogical practice.

IMPLICATIONS

Despite these limitations, the results show some interesting trends that bear further exploration and examination. Specifically, the data from this study implies that metacognitive awareness can be more successfully fostered in student writers if instructors combine traditional approaches to encouraging metacognitive awareness (e.g., keeping a writing process journal, analyzing one’s genre and audience before beginning to write, engaging in peer review, writing reflections on one’s writing process, and having explicit discussions about threshold concepts or writing strategies) with contemplative or mindful practices intended to help students develop a greater awareness of their own internal states as well as a discipline of present-moment awareness (e.g., mindfulness meditations, body scans, yoga). Contemplative and mindful pedagogical approaches are, perhaps, uniquely capable of facilitating metacognition among writing students because of the ways in which these approaches attend to the overlap between the cognitive, emotional, and embodied aspects of learning. As noted previously, the field of writing studies has become increasingly aware of the role that emotions and dispositions play in the writing process, especially regarding the development of metacognition and successful knowledge transfer (Driscoll and Powell; Driscoll and Wells). Unlike some traditional pedagogical approaches that prioritize the role of the cognitive or the intellectual in learning, contemplative and mindful pedagogical approaches are built upon the premise that learning encompasses and involves the whole person. As Parker Palmer and Arthur Zajonc note:

The wish to comprehend leads us to develop methods of inquiry directed toward reliable knowledge. If the methods we possess are fragmented or partial, then our knowledge will be likewise. In this way we see that an expanded ontology requires an enriched epistemology. The richness of the world will not reveal itself by a single means of inquiry. Not only are many questions required, but they must be posed and explored in different ways, each one of which illuminates the world from another direction, inner as well as outer. (93)

In addition to the scholarship of contemplative and mindful pedagogues like Parker Palmer, Mary Rose O’Reilley, Sondra Perl, Christy Wenger, and Alexandria Peary, scholars in educational psychology and cognitive science have also conducted research which indicates that mindfulness meditation activities can improve attention, memory, emotional regulation, and executive functioning—all of which are capacities that are directly connected to the development of metacognition (Hart; Roeser and Peck; Zajonc; Norris et al.; Zhang et al.). Scholarship from these different fields can be combined with research on the best practices of teaching writing to better foster the development of metacognition and successful transfer of knowledge in students.

I hope that scholars in the field recognize the potential of contemplative and mindful pedagogical approaches and continue to study the efficacy of these approaches in the writing class. Some possible classroom applications for further investigation and experimentation might include a mixture of the following:

-

daily or weekly teacher-led mindfulness practices (e.g., guided meditations, breathwork, yoga, tai chi) to encourage students to develop a discipline of dispositional introspection, bodily awareness, and present moment awareness;

-

planned and consistent classroom discussions that require students to pause at whatever stage they are currently at in the writing process, assess how and why they got to this point, and determine their next best steps;

-

encouraging students to take up this practice of in-the-moment-pauses when they are working on their assignments at home or in their dorm rooms;

-

requiring students to keep a daily log or journal that describes each stage of their writing process for that day, as well as their level of motivation, and their physical and emotional state; and

-

systematically integrating mindfulness activities into each phase of the writing process: planning (e.g., mindful freewriting or drawing), drafting (e.g., planned pauses to assess progress and next steps), and revision (e.g., including meta-comments on drafts before submitting them for peer review).

Current research on metacognition in writing studies shows us that it is imperative for students to develop a metacognitive awareness of their writing process in order for the skills they learn in first-year composition and foundational writing classes to transfer to other settings. However, growing distractions and stressors on college students (not the least of which include an ongoing global pandemic, the increasingly severe impacts of climate change, and the ever-present threat of gun violence on campus—in addition to the more mundane distractions provided by smartphones and other technologies, anxiety about grades, and homesickness) make the probability that this kind of awareness will develop without any intervention by the instructor very unlikely. Instructors of writing must consider how they can create the space—in their classrooms and in their pedagogy—for students to pause, honor, and take stock of their internal states in the present moment, in order to develop the mindfulness skills necessary for metacognition and transfer.

Appendix: Schraw and Dennison’s (1994) Metacognitive Awareness Inventory

Note: DK, declarative knowledge; PK, procedural knowledge; CK, conditional knowledge; P, planning; IMS, information management strategies; M, monitoring; OS, debugging strategies; and E, evaluation

-

I ask myself periodically if I am meeting my goals. (M)

-

I consider several alternatives to a problem before I answer. (M)

-

I try to use strategies that have worked in the past. (PK)

-

I pace myself while learning in order to have enough time. (P)

-

I understand my intellectual strengths and weaknesses. (DK)

-

I think about what I really need to learn before I begin a task. (P)

-

I know how well I did once I finish a test. (E)

-

I set specific goals before I begin a task. (P)

-

I slow down when I encounter important information. (IMS)

-

I know what kind of information is most important to learn. (DK)

-

I ask myself if I have considered all options when solving a problem. (M)

-

I am good at organizing information. (DK)

-

I consciously focus my attention on important information. (IMS)

-

I have a specific purpose for each strategy I use. (PK)

-

I learn best when I know something about the topic. (CK)

-

I know what the teacher expects me to learn. (DK)

-

I am good at remembering information. (DK)

-

I use different learning strategies depending on the situation. (CK)

-

I ask myself if there was an easier way to do things after I finish a task. (E)

-

I have control over how well I learn. (DK)

-

I periodically review to help me understand important relationships. (M)

-

I ask myself questions about the material before I begin. (P)

-

I think of several ways to solve a problem and choose the best one. (P)

-

I summarize what I've learned after I finish. (E)

-

I ask others for help when I don't understand something. (DS)

-

I can motivate myself to learn when I need to. (CK)

-

I am aware of what strategies I use when I study. (PK)

-

I find myself analyzing the usefulness of strategies while I study. (M)

-

I use my intellectual strengths to compensate for my weaknesses. (CK)

-

I focus on the meaning and significance of new information. (IMS)

-

I create my own examples to make information more meaningful. (IMS)

-

I am a good judge of how well I understand something. (DK)

-

I find myself using helpful learning strategies automatically. (PK)

-

I find myself pausing regularly to check my comprehension. (M)

-

I know when each strategy I use will be most effective. (CK)

-

I ask myself how well I accomplished my goals once I'm finished. (E)

-

I draw pictures or diagrams to help me understand while learning. (IMS)

-

I ask myself if I have considered all options after I solve a problem. (E)

-

I try to translate new information into my own words. (IMS)

-

I change strategies when I fail to understand. (DS)

-

I use the organizational structure of the text to help me learn.

-

I read instructions carefully before I begin a task. (P)

-

I ask myself if what I'm reading is related to what I already know. (IMS)

-

I reevaluate my assumptions when I get confused. (DS)

-

I organize my time to best accomplish my goals. (P)

-

I learn more when I am interested in the topic. (DK)

-

I try to break studying down into smaller steps. (IMS)

-

I focus on overall meaning rather than specifics. (IMS)

-

I ask myself questions about how well I am doing while I am learning something new. (M)

-

I ask myself if I learned as much as I could have once I finish a task. (E)

-

I stop and go back over new information that is not clear. (DS)

-

I stop and reread when I get confused. (OS)

Works Cited

Barbezat, Daniel P., and Mirabai Bush. Contemplative Practices in Higher Education: Powerful Methods to Transform Teaching and Learning. Jossey-Bass, 2014.

Carillo, Ellen C. The Evolving Relationship Between Composition and Cognitive Studies: Gaining Some Historical Perspective on our Contemporary Moment. Contemporary Perspectives on Cognition and Writing, edited by Patricia Portanova et al., University Press of Colorado, 2017, pp. 39-55.

Chaterdon, Kate. Writing Into Awareness: How Metacognitive Awareness Can Be Encouraged Through Contemplative Teaching Practices. Across the Disciplines: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Language, Learning, and Academic Writing, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, pp. 50-65, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/contemplative/chaterdon2019.pdf.

Costa, Arthur and Pat Wilson O’Leary. The Power of the Social Brain: Teaching, Learning, and Interdependent Thinking. Teachers College Press, 2013.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn. Connected, Disconnected, or Uncertain: Student Attitudes about Future Writing Contexts and Perceptions of Transfer from First Year Writing to the Disciplines. Across the Disciplines, vol. 8, no. 2, 2011, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/articles/driscoll2011.pdf.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Roger Powell. States, Traits, and Dispositions: The Impact of Emotion on Writing Development and Writing Transfer Across College Courses and Beyond. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://compositionforum.com/issue/34/states-traits.php.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php.

Downs, Doug, and Elizabeth Wardle. Teaching About Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning ‘First-Year Composition’ as ‘Introduction to Writing Studies.’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no. 4, 2007, pp. 552-84.

Foehr, Regina Paxton, and Susan A. Schiller. The Spiritual Side of Writing. Boynton/Cook Publishers, 1997.

Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing. Council of Writing Program Administrators et al. Jan. 2011, https://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf.

Gorzelsky, Gwen, et al. Cultivating Constructive Metacogntion: A New Taxonomy for Writing Studies. Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer, edited by Chris M. Anson and Jessie L. Moore, University Press of Colorado, 2017, pp. 215-246, doi:10.37514/PER-B.2016.0797.2.08.

Gorzelsky, Gwen, et al. Meaningful Practice: Adaptive Learning, Writing Instruction, and Writing Research. Contemporary Perspectives on Cognition and Writing, edited by Patricia Portanova et al., University Press of Colorado, 2017, pp. 115-132, doi: 10.37514/PER-B.2017.0032.2.06.

Hall, E. Ashley, et al. A Metacognitive Strategy for Iterative Drafting and Revising. Using Reflection and Metacognition to Improve Student Learning: Across the Disciplines, Across the Academy, edited by Matthew Kaplan et al., Stylus, 2013, pp. 147-166.

Hart, Tobin. Interiority and Education: Exploring the Neurophenomenology of Contemplation and its Potential Role in Learning. Journal of Transformative Education, vol. 6, no. 4, 2008, pp. 235-250.

Hart, Tobin. Opening the Contemplative Mind in the Classroom. Journal of Transformative Education, vol. 2, no. 1, 2004, pp. 28-46.

Haskell, Robert E. Transfer of Learning: Cognition, Instruction, and Reasoning. Academic Press, 2001.

Haswell, Richard H. NCTE/CCCCs Recent War on Scholarship. Written Communication, vol. 22, no. 2, 2005, 198-223.

Jackson, Brian. Teaching Mindful Writers. Utah State University Press, 2020.

Johanek, Cindy. Composing Research: A Contextualist Paradigm for Rhetoric and Composition. Utah State University Press, 2000.

LaVaque-Manty, Mika, and E. Margaret Evans. Implementing Metacognitive Interventions in Disciplinary Writing Classes. Using Reflection and Metacognition to Improve Student Learning: Across the Disciplines, Across the Academy, edited by Matthew Kaplan et al., Sterling, Virginia: Stylus, 2013, pp. 122-142.

MacArthur, Charles A. et al. Self-Regulated Strategy Instruction in College Developmental Writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 107, no. 3, 2015, pp. 855-867.

Moffett, James. Writing, Inner speech, and Meditation. College English, vol. 44, no. 3, 1982, pp. 231-46.

Moore, Jessie L., and Randall Bass, editors. Understanding Writing Transfer: Implications for Transformative Student Learning in Higher Education. Stylus, 2017.

Newbury, Melissa, et al., editors. Emotion in Schools Understanding How the Hidden Curriculum Influences Relationships, Leadership, Teaching, and Learning. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2013.

Norris, Catherine J., et al. Brief Mindfulness Meditation Improves Attention in Novices: Evidence From ERPs and Moderation by Neuroticism. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 12, 2018, doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00315.

Nowacek, Rebecca. Agents of Integration: Understanding Transfer as a Rhetorical Act. Southern Illinois University Press, 2011.

O’Reilley, Mary R. Radical Presence: Teaching as Contemplative Practice. Boynton/Cook, 1998.

Palmer, Parker. The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. Jossey-Bass, 1998.

Palmer, Parker, and Arthur Zajonc. The Heart of Higher Education: A Call to Renewal. Jossey-Bass, 2010.

Peary, Alexandria. Prolific Moment: Theory and Practice of Mindfulness for Writing. Routledge, 2018.

Perl, Sondra. Felt Sense: Writing with The Body. Heinemann, 2004.

Reid, E. Shelley. Defining Dispositions: Mapping Student Attitudes and Strategies in College Composition. Contemporary Perspectives on Cognition and Writing, edited by Patricia Portanova et al., University Press of Colorado, 2017, pp. 291-312, doi:10.37514/PER-B.2017.0032.2.15.

Roeser, Robert, and Stephen Peck. An Education in Awareness: Self, Motivation, and Self-regulated Learning in Contemplative Perspective. Educational Psychologist, vol. 44, no. 2, 2009, pp. 119-136.

Schraw, Gregory, and Rayne Sperling Dennison. Assessing Metacognitive Awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, vol. 19, 1994, pp. 460-475.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Creative Repurposing for Expansive Learning: Considering ‘Problem-Exploring’ and ‘Answer-Getting’ Dispositions in Individuals and Fields. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012. https://compositionforum.org/issue/26/creative-repurposing.php.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Understanding ‘Transfer’ from FYC: Preliminary Results of a Longitudinal Study. WPA, vol. 31, no. 1-2, 2007, pp. 65-85.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and Doug Downs. Writing About Writing. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2017.

Wenger, Christy I. Yoga Minds, Writing Bodies: Contemplative Writing Pedagogy. The WAC Clearinghouse, Parlor Press, 2015, doi:10.37514/PER-B.2015.0636.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, editor. A Rhetoric of Reflection. Utah State University Press, 2016.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. Reflection in the Writing Class. Utah State University Press, 1998.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, et al. Writing Across College: Key Terms and Multiple Contexts as Factors Promoting Students’ Transfer of Writing Knowledge and Practice. WAC Journal, vol. 29, 2018, pp. 42-63, doi:10.37514/WAC-J.2018.29.1.02.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, et al. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State University Press, 2014.

Zajonc, Arthur. Contemplative Pedagogy: A Quiet Revolution in Higher Education. Contemplative Studies in Higher Education. Special issue of New Directions for Teaching and Learning, vol. 134, 2013, pp. 83-94.

Zhang, Qin, et al. The Effects of Different Stages of Mindfulness Meditation Training on Emotion Regulation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 13, 2019, doi:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00208.

Mindful Practice & Metacognitive Awareness from Composition Forum 50 (Fall 2022)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/50/mindful-practice.php

© Copyright 2022 Kate Chaterdon.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 50 table of contents.