Composition Forum 49, Summer 2022

http://compositionforum.com/issue/49/

Participant Coding in Discourse-Based Interviews Capable of Supporting the Inferences Required to Describe a Theory of Transfer

Abstract: Discourse-based interviews allow researchers to gather data about a writer’s understanding of what informs a task. This method was essential for a research team seeking to understand the impact of programmatic learning objectives on student writing development. Three decisions in the approach to this research project sought to center the student participants and make them quasi-researchers: the alignment of a clearly articulated theoretical framework with the methodology, the collection of supporting data from other methods, and modifications to the interview protocol. The study found that a writing program can facilitate the transfer of writing skills by implementing consistent, explicit, and intentional transfer-oriented learning objectives in both FYC and advanced composition courses.

From 2011-2013, four researchers from the University of California, Davis participated in the Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer research seminar hosted by Elon University. The seminar provided our team with opportunities to collaborate with scholars from several disciplinary backgrounds during the development and execution of a research project (Hayes et al.). The project’s research question was as follows: “What impact do transfer-oriented learning objectives have on student writing development at a large public university’s writing program?” For the study, we examined writing contexts in both lower- and upper-division composition courses. Discourse-based interviews became an early candidate for data collection because a central goal to the study was to “determine what assumptions writers made or what background knowledge they had concerning the audience, the topic, and the strategies that might be appropriate for achieving their assigned purpose with a given audience” (Odell et al. 222). With a research question that focused on how students interacted with programmatic learning outcomes, DBIs were not only a way to bring together student understandings, student texts, and learning goals, DBIs also provided a way to make inferences across this diverse pool of data.

The development of the methodology was guided by the theoretical framework we selected during our time at the research seminar. While aligning our methodology with that framework, the team recognized DBIs as a data collection instrument well suited to the research question. That alignment process did, however, require us to make significant modifications to the interview protocol. Our DBI procedure would focus on how writers understood learning objectives rather than “the types of stylistic and substantive features of a text” examined in earlier uses of the DBI (Herrington 337). We also included modifications intended to address concerns raised by Kevin Roozen (250) about the tacit representations of writing that researchers bring to an investigation.

An essential early step was to align the research questions, the theoretical framework, and the method for gathering and analyzing data. We begin this description of our approach to the DBI by retracing the steps we took when deciding on a theoretical framework. That path helps explain two features of the study’s methodology. First, it explains the way data gathered through DBIs contributes to a description of writing development. Second, the path to our theory highlights the reasons we modified the DBI protocol. In our review of investigations into knowledge transfer, we found most researchers drawing from three categories of research methods, each is shaped by different theories of knowledge transfer. For each of these approaches, data collection choices were guided by the theories scholars used to describe how prior knowledge gets used in new settings. In order to decide what kinds of methods we would use, we first needed to identify a theory of transfer capable of describing the kind of writing development we sought to investigate.

Using the Theoretical Framework to Determine Data Collection Methods

The theories of learning transfer that shaped our work came from the disciplines of education, cognitive psychology, teaching English to speakers of other languages, and rhetoric and composition. Many of the sessions and discussions at the Critical Transitions seminar worked to synthesize how these different disciplines investigate what happens when learners utilize prior knowledge in a new context. This effort brought to light a theoretical divide that had been articulated decades earlier. In an influential article, Patricia Bizzell asserted that a description of writing ability must consider “the cognitive and the social factors in writing development” (392), categorizing previous research as inner-directed and outer-directed respectively. Bizzell noted that much of the prior research examined one factor or the other. She argued, however, that consideration of both factors is important because successful writers must learn how to frame their thinking using the resources provided by the community for which they are writing.

Through the seminar’s collaboratively built review of literature on learning transfer, we found that much of the research done in education and cognitive psychology was focused on what Bizzell would term outer-directed research. Studies in these areas followed the lead of Mary L. Gick and Keith J. Holyoak’s investigation into analogical thinking. Their study involved altering conditions in the learning environment to see how that would impact performance later. Other researchers have investigated how changes in the assessment setting impacted the utilization of prior knowledge (Chen and Klahr) or how the framing of the learning context impacted knowledge transfer (Engle et al.). The methods education researchers used to perform these outer-directed studies utilized various pre-test/post-test models to assess how learners perform when there are changes in the learning and assessment contexts.

Investigations of transfer in writing studies, on the other hand, were more often inner-directed—focusing on the thinking processes, reflections, and experiences of learners. Many of the theoretical frameworks for these studies were rooted in the work of David N. Perkins and Gavriel Salomon, who developed a high-road/low-road cognitive model of transfer. That model described the kinds of thinking a learner must do to effectively utilize prior knowledge in a new setting. Working from this framework led researchers to use interviews (e.g. Brent) and survey data (e.g. Driscoll) to better understand the thought processes and/or dispositions of learners as they wrote across different contexts.

The studies that focused on either the student or the social context contributed to our understanding of how different research methodologies explore facets of learning transfer. That understanding provided context for a third set of studies, studies with research questions similar to those we were pursuing. The researchers in question were inquiring into how writing development is shaped by a learner’s interactions with an institution of higher education (Beaufort; Wardle; Yancey et al.). That research required taking up Bizzell’s call to describe the relationship between the cognitive processes of learners and the social environments in which those learners work (391). Consistently across these studies, this task was accomplished through the application of theoretical frameworks which called for data collected using methodologies informed by both the outer and inner-directed approaches.

For example, Anne Beaufort’s longitudinal case study of one student’s development as a writer opens with a theory that names the knowledge domains which writers must develop if they are to become experts within a discourse community. That work had a major impact on Kathleen Blake Yancey, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak’s Writing Across Contexts. Their book described the impact of a transfer-oriented FYC curriculum. The study was framed by a theory of writing development that emphasized the importance of learners having appropriate language to describe a rhetorical situation and then having opportunities to reflect using that language while learning to write in new settings. Elizabeth Wardle’s study of FYC at a large public university lays out a theoretical framework that brings together (A) an emphasis on the cognitive with Perkins and Salomon’s ideas on transfer, and (B) the social elements of genre theory, activity theory, and post-process critiques of composition. A crucial step in each study was articulating a coherent theoretical framework that required data on both cognitive and social features of writing development.

This steered our project towards the use of dynamic transfer as a theoretical framework, as articulated by Lee Martin and Daniel Schwartz. Dynamic transfer “occurs when people coordinate multiple conceptual components, often through interaction with the environment, to create an innovation” (450). Dynamic transfer is similar to Michael-John DePalma and Jeffrey M. Ringer’s conceptualization of transfer for L2 writing and composition, which they termed adaptive transfer. Both use the term “dynamic” to present a flexible way of framing the concept of transfer, allowing for the changes that prior knowledge must undergo when applied in new settings. Adaptive transfer is further defined using terms more commonly used in L2 writing and composition research, such as idiosyncratic, cross-contextual, rhetorical, multilingual, and transformative (141). Dynamic transfer, developed within the field of educational psychology, can be distinguished from adaptive transfer by its explicit focus on the external resources learners use to change prior knowledge for a new context. External resources in dynamic transfer are part of the mechanics required to develop new understandings through a learner’s coordination of ideas and materials while working towards a goal. The process requires time and a setting in which learners can overcome obstacles through trials and interactions. This is particularly important when the new problem is complex or ill-defined—for example, discipline-based writing problems that may introduce new materials to the writing process such as lab equipment, new media, or data collection protocols. In such situations, there are many concepts to keep track of, and multiple potential solutions. These circumstances require a person to distribute some of the cognitive work into the environment, attempt solutions, get feedback, and seek out other resources capable of supporting the endeavor.

When dynamic transfer shapes writing development, a learner coordinates prior knowledge along with several resources to facilitate a context-bound learning-to-write process. When this type of transfer occurs, the act of writing becomes what Janet Emig described as “a unique mode of learning” (122), one that coordinates prior knowledge with the situated nature of the task. Any attempt to study these activities requires two types of data:

-

The socially constructed resources that shape a writing task;

-

The way writers understand and interact with those resources.

The research team recognized DBIs as a potential tool because they have been used in conjunction with other data collection methods “to understand the context for... writing and the relation of [the] writing to that context” (Herrington 334). In studies that incorporated multiple methods, DBIs have not only provided useful data, they have also helped to synthesize and contextualize data collected via other methods.

Collecting Data to Support the DBI

The choice to combine data from student interviews with data collected from other methods, such as surveys or course descriptions, was not unique to our research project. Chris Thaiss and Terry Myers Zawacki’s four-year study of writing across the curriculum at one institution utilized interviews with students, interviews with faculty, department rubrics, writing task descriptions, and writing samples. Similarly, Anne Herrington’s investigation into the writing contexts in chemical engineering courses utilized DBIs, surveys, instructor interviews, course observations, and analyses of student writing. Modeling this practice, our research team planned to combine the results of DBIs with data from a survey and an analysis of writing program documents. The survey sought data that describe the student population. It also inquired into how students did or did not view the lower- and upper-division writing courses as a set of linked experiences contributing to the development of a set of subskills. Other data was collected through the analysis of writing program documents. The discourse-based interviews as well as a set of codes used to analyze the eventual interview results were derived from programmatic learning objectives described in the program description: incorporating evidence appropriate for the task, demonstrating awareness of audience, producing purpose-driven texts, using language effectively, and collaborating with others during the writing process. The semi-structured interviews used these objectives as a guide, and they served as the initial codes during the first pass of data analysis.

The survey provided a more complete understanding of how students interacted with the writing context we sought to investigate. The 21-item online survey (see Appendix) was administered to 728 students enrolled in upper-division writing courses. This sample was composed entirely of students at the University of California, Davis, a large public research university with competitive admissions that enrolls about 25,000 undergraduates. Over 80% of those surveyed were born in the US. Nearly all obtained their education in the US and graduated from US secondary schools. About 60% of the students were raised in homes where family members spoke a language other than English. About 35% of students were required to take one or more remedial entry-level writing courses before they were allowed to enroll in a lower-division writing course.

On the survey, students self-reported their history of writing instruction, linguistic background, and their perceptions of academic writing. The majority of participants reported being comfortable with all but one of the fifteen academic subskills associated with writing in upper-division courses—the one exception being timed writing tasks. From the entire sample, 84.6% reported that lower-division writing courses had helped them develop the subskills they had ranked (Hayes et al. 203). These data supported assumptions that students understood lower- and upper-division writing courses as separate-yet-linked settings where writing development takes place over time. Empirical evidence supporting that assumption was crucial in the preparation of DBIs because we sought to interview participants who were at different stages within the writing program.

The analysis of writing program documents involved the review of instructor training procedures, instructor evaluation procedures, standard syllabi for first-time instructors, learning objectives, prerequisites for upper-division courses, and upper-division course descriptions. This data yielded codes that would be used in the analysis of student texts, the development of the DBI protocol, and the analysis of the DBI results. The first set of codes to emerge were linked to the research question and the program’s explicit transfer-oriented learning objectives. The program documents also described resources available to students in the writing program. Identifying these resources led to the development of codes used to analyze the interview transcripts for resources that facilitated dynamic transfer (see Table 1).

Table 1. Writing Resources Identified in the Writing Program

|

Code |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Instructor feedback |

Meetings with instructors during which specific writing projects are discussed and the instructor provides constructive feedback |

|

Model texts

|

Texts that model specific styles or techniques |

|

Revision opportunities |

Timeframes and/or planning for writing tasks allow or require multiple revisions |

|

Explicit metacognitive reflection |

Course activities that require students to reflect on their own writing process |

|

Peer collaboration |

Opportunity or requirement to share drafts with peers |

Developing an Interview Protocol

Having collected the supporting data required to move forward, the research team began developing a protocol for the DBIs. The initial design was similar to the practical example provided by Herrington’s examination of writing in chemical engineering courses. Those interviews were guided by the lab and design reports composed by student work groups. To prepare, Herrington highlighted specific occurrences of stylistic and substantive features in the texts and then asked student writers if they would accept suggested edits or revisions. The responses in that study “obtained the independent perceptions of writers ... about the same features of text” (337). Like Herrington, our research team sought interview data able to describe what we could not see, such as feelings or the way people interpret their writing process (Merriam). The protocol, therefore, would be built around participant-produced texts, and questions would call on participants to share their perceptions of those texts.

We were aware, however, of a methodological critique of such interviews. Roozen has noted that researchers are unlikely to observe “the tacit representations of writing and literate activity that drive research designs” (251). Roozen’s effort to mitigate this issue involves open-ended interview questions that call on writers to (A) reflect on their process and literacy experiences, and/or (B) interact with texts they are familiar with. Our protocol would be based primarily on the latter approach, with Roozen’s critique shaping an important aspect of the interview protocol: our research team did not select portions of the text as appropriate sites of inquiry as Herrington had done, because that is one place where tacit representations of literate activity get hidden within a protocol. Instead, we began developing questions using the writing program’s explicit representations of literate activity—the programmatic learning objectives. So, instead of seeking “the independent perceptions of writers” about features of a text selected by the researcher (Herrington 337), we worked to obtain independent perceptions about how writers believed their writing demonstrated programmatic learning objectives—objectives explicitly built into each course.

When we shifted the DBI protocol away from researcher-selected features of a text, we had partially addressed the obstacle presented by tacit representations of writing. The shift to learning outcomes, however, created another site for that limitation to emerge. Our research team was composed of writing program instructors and administrators, a group that viewed learning objectives and outcomes in ways that certainly included tacit representations of writing. The interview protocol, therefore, needed to build a methodological wall between (A) the way participants understood those learning objectives as potential resources for writing situations, and (B) the way the writing program used them as tools for programmatic assessment and the assessment of student writing. Such a wall would allow us to capture data that emphasized how students understood learning outcomes—specifically, how they understood them as resources at work in the process of dynamic transfer. The interview, therefore, needed to grant the participants control over how those outcomes were brought to the research setting and how they were categorized within it. For this reason, we introduced two methodological innovations: participant-selected texts and the participant coding of those texts.

We introduced both of these changes to the interview protocol because of the ways learning objectives are associated with writing assessment. An important area of inquiry within the writing assessment community examines the ways power and positionality are built into assessment. Asao B. Inoue has called on researchers and administrators working in the area of assessment to consider “how much control and decision-making ... students have in the creation and implementation of all assessment processes and parts?” (288). Brian Huot and Michael Williamson argued that the sites where student writing has historically been assessed were all-too-often centrally located and as a result, decisions about the text were made without input from the writer. This is why we sought a way to shift power back to the study’s student writer participants.

This first way to facilitate this shift involved text selection for the DBIs. In her 1985 study, Herrington had selected a benchmark assignment that all of the participants had completed. The consistency across texts in that interview protocol increased the reliability of the study’s analysis. Our protocol forwent this type of reliability when we modified our recruitment procedure, requesting each participant select texts they believed best demonstrated their own writing ability. While the reliability of data analysis is certainly important in any systematic study of writing development, the shift we made is aligned with how the assessment community has come to understand the relationship between reliability and validity (Moss). Carl Whithaus noted that “validity has begun to move away from an empiricist notion of objectively determined accuracy” and has shifted instead into a more constructivist notion of the sociocultural making of meaning. It is a move away from assignments and assessments used “as ways to ‘sort’ students or demand mastery of certain ‘skills’ outside the context of a specific piece of writing” (Huot 61). It is a move towards inviting students into the assessment not only of the writing, but also of the contexts that shape the writing. We incorporated this shift into the interviews when we requested student-selected writing samples during our recruiting procedure.

To further incorporate this constructivist notion into our protocol, we turned to features from the think aloud research protocol, a qualitative research method capable of collecting data on higher order thinking processes (Olson et al.). Think aloud methods originated in cognitive psychology and can be used to call on participants to “explore their writing processes as quasi-researchers” (Charters 78). This concept of participants as quasi-researchers shaped our interview questions. We invited participants to consider each learning objective, review their own writing samples, and code the texts themselves. The learning objectives used to guide the core interview questions were the following:

-

incorporating evidence appropriate for the task;

-

demonstrating awareness of audience;

-

producing purpose-driven texts;

-

using language effectively;

-

collaborating with others during the writing process.

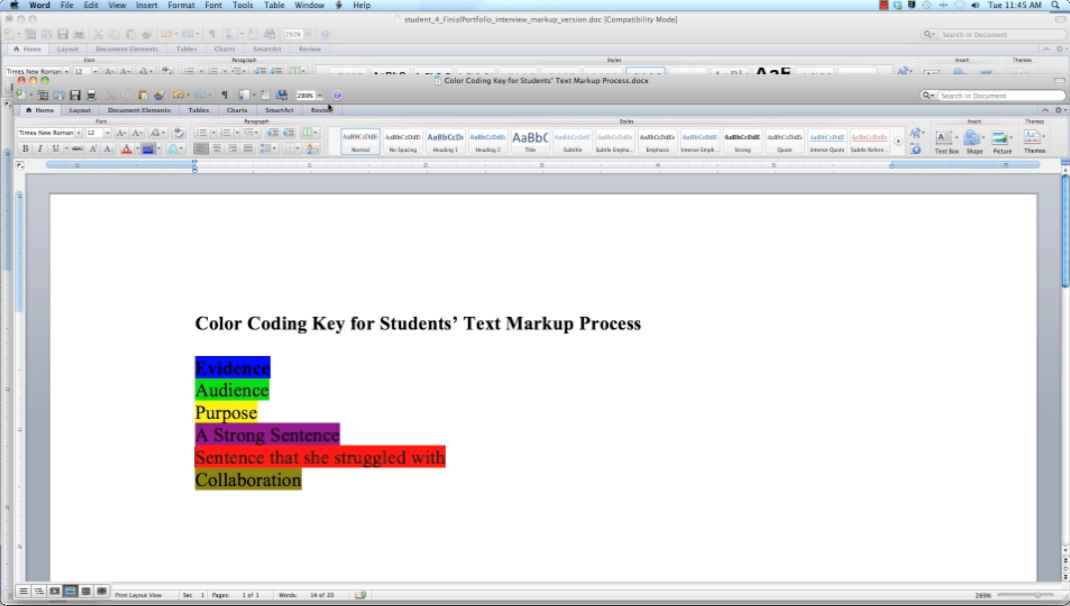

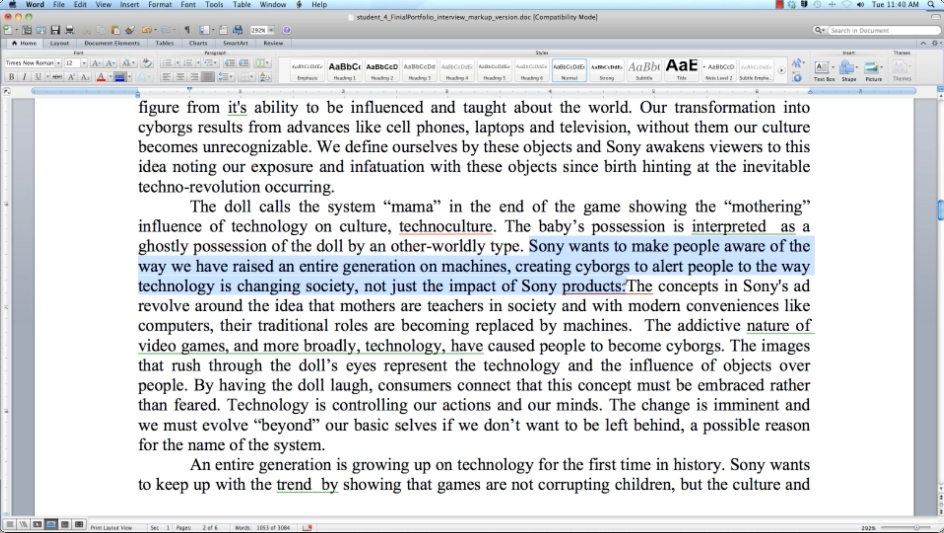

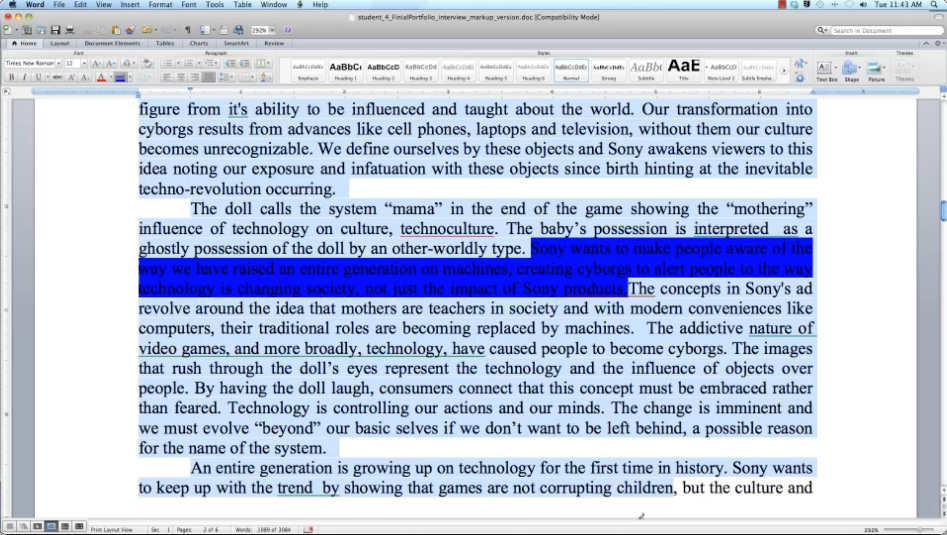

Technology made this feature of the interview protocol possible. We displayed writing samples on a computer monitor and used screen capture software to record both interview audio and on-screen activity (see Figures 1-3). Each interview recording featured participants walking through the thought process of considering their own writing, selecting passages, and reflecting on why they believed those passages demonstrated various learning outcomes.

Figure 1. Color coding key presented to participants

Figure 2. Student 4 initially marking a claim using bold to seek out evidence

Figure 3. Student 4 marking evidence around the claim they highlighted initially

Methodologically, the shifts we incorporated provided a way to identify how students understand and use socially constructed resources such as learning objectives. Our theoretical framework is what helped us identify ways to modify the DBI protocol. The framework called for data that describe how participants understood the learning objectives, as opposed to how the writing program understood those outcomes. Inviting the participants into the decision-making process was an effective way for the research team to develop “categories from informants rather than specifying them in advance of the research” (Creswell 77). The modified protocol was a way of acknowledging that a portion of data analysis is built into the data collection method. The DBIs we conducted contributed to interview data that, when further analyzed, could describe both (A) the resources participants used, and (B) how participants understood and thought about those resources.

The result of these considerations was the following protocol:

-

When recruited, participants were asked to select writing samples from the writing course they had most recently completed.

-

Interviews were conducted by one member of the research team.

-

Sample texts selected by interviewees were the focus of the interview.

-

The texts were sent to the interviewer ahead of time. At the start of the session, the texts were displayed for both the participant and the interviewer on a computer monitor.

-

-

After participants reviewed and signed consent forms, Camtasia software was activated to record the interview audio and, simultaneously, screen-captured video of interactions with the text on the computer monitor.

-

The interviews did not capture video of the participant and/or interviewer.

-

-

Each interview began with several introductory questions about how the participant was feeling that day, the participant’s major, and the course(s) for which the writing samples were composed.

-

The interview then turned to the texts, asking the participant to review their writing samples and select an excerpt that illustrated one of the program-based learning objectives.

-

This normally started with the first learning objective, incorporating evidence appropriate for the task. Interviewers were able, however, to change the order in which these questions were asked if such a change would make the interview move along more smoothly.

-

-

The participant was instructed to share their thoughts as they used the word processor’s text highlighting tool to mark the excerpt they selected.

-

For each learning objective, the participant used a unique highlighting color.

-

-

The interviewer then prompted the participant to explain or talk more about their selection. The goal was to understand why/how the participant believed the highlighted text illustrated the chosen learning objective.

-

If the open-ended invitation to discuss the except did not yield answers about the learning objective in question, the interviewer used additional probes (Berg & Lune), reminding participants about what the original question had focused on.

-

-

This “select, highlight, and reflect” procedure was repeated for each of the learning objectives.

-

Student-coded texts were saved as a new document.

Data Analysis

The interviews ranged from 30-45 minutes long. We conducted a total of fourteen interviews, eight with students in the lower-division setting and six with upper-division students. Participants represented a range of different majors. The full procedure yielded four types of data: participant-selected writing samples, participant-coded writing samples, the interview transcript, and a screen-capture video of participant interactions with the texts. These rich sources of data required a systematic approach to analysis, especially when combined with the complimentary data collected via surveys and the initial analysis of writing program documents.

Table 2. Summary of interviewees

|

Student # |

Major |

Course Taken |

Lower- or Upper-Division |

Text Samples Provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Science and Technology Studies |

Expository Writing |

Lower-division |

Portfolio letter, ad analysis, personal narrative |

|

2 |

Spanish |

Expository Writing |

Lower-division |

Portfolio letter, essay on computers, essay on cyber-bullying |

|

3 |

Economics |

Expository Writing |

Lower-division |

In-class academic essay, social narrative, ad analysis |

|

4 |

Computer Science |

Expository Writing |

Lower-division |

Portfolio letter, personal narrative, social narrative |

|

5 |

Economics |

Expository Writing |

Lower-division |

Portfolio letter, literacy narrative, argumentative essay |

|

6 |

Biological Science |

Expository Writing |

Lower-division |

Portfolio letter, research essay, argument |

|

7 |

Undeclared |

Expository Writing |

Lower-division |

Rhetorical analysis, literacy narrative, problem paper |

|

8 |

Undeclared |

Expository Writing |

Lower-division |

Literacy narrative, rhetorical analysis |

|

9 |

Philosophy and Sociology |

Advanced Composition |

Upper-division |

Critical response 1, critical response 2 |

|

10 |

Food Science |

Business Writing |

Upper-division |

Memo |

|

11 |

Human Development |

Writing for Health Sciences |

Upper-division |

Rhetorical analysis, profile, collage |

|

12 |

Microbiology |

Writing for Health Sciences |

Upper-division |

Profile, case study, ad analysis |

|

13 |

Economics |

Advanced Composition |

Upper-division |

Mid-term, critical response |

|

14 |

Mechanical Engineering |

Writing for Engineering |

Upper-division |

Engineering management report, memo, revision plan |

The analysis of DBI results took place in three stages. For the first stage, the research team coded the unmarked versions of the participant writing samples for the same learning objectives we had asked about during the DBI. As a team, we worked through a series of norming sessions until we were confident that our use of those initial codes was consistent. We then moved into a second stage where the researcher-coded texts were compared to the participant-coded texts. Analysis at this stage started as a group discussion among the research team. We discussed discrepancies and similarities between researcher-coded texts and participant-coded texts. We started to sketch out relationships between learning objectives and participant perceptions using a constant comparison process (Glaser and Strauss). This stage resulted in a refined set of codes that were used to inform our conclusions (see Table 2). These codes were then used in a third stage to refine our descriptions of the relationships between data from the interviews, the writing samples, and the writing resources identified during the analysis of writing program documents (see Table 1).

Table 3. Refined Codes Used During the Second Stage of Analysis

|

Code |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Audience |

The writer directly addresses the audience or provides text that explicitly guides the reader. |

|

Purpose |

The writer explicitly or implicitly signals the overall purpose of the text (similar but not identical to “thesis”). |

|

Claim |

The writer makes a claim, whether from his or her own opinion or from a source. |

|

Evidence |

The writer uses information from sources and/or real-world examples to support claims. |

|

Reflection |

The writer describes a lesson learned or an insight about an experience and/or his or her own writing. |

Conclusions and Evaluation of the DBI Approach

The conclusions we reached based on the DBIs were reported in two sets. The first set of conclusions was a summary of resources that support writing development in the lower- and upper-division settings. The resources we identified included constructive feedback, model texts, revision opportunities, explicit calls for metacognitive reflection, and peer collaboration. While most of these resources were identified during the analysis of program documents, the DBIs were used to demonstrate how various forms of support were utilized by students. The second set of conclusions reached using the DBI data were presented as a series of what Ted Wragg termed as critical events. The use of the word critical is not used to suggest a positive nor a negative quality, but rather to designate that an event is “judged to be illustrative of some salient aspect of ” the study (Wragg 67). In this case, we presented four events that illustrate aspects of the process of dynamic transfer at work. The first critical event described a lower-division student struggling to identify where they had used evidence to support a claim. This event was selected because the reading associated with the assignment was a very advanced text from a specialized disciplinary area. The student’s response, demonstrated in Figures 1-3, showed that they were still working on understanding how to link claims and evidence in their own writing while working with such a complex text: asked to mark the evidence for a claim, they highlighted all the entire surrounding text. The second critical event summarized the portion of an interview with a lower-division student working to show a passage they had struggled to write. The student was trying to move beyond the convention of rephrasing the introduction, and they used their new understanding of “exigence” to do so. The third critical event described an upper division student who dismissed the need for audience awareness on an assignment, suggesting they believed the only potential audience for the task in question was the professor. Less than a minute later, the same student said of their own thinking process, “Okay, so the person who would be reading this would be, um, somebody looking up on CNN.com or something.” The fourth critical event showed how the work done by an upper-division student demonstrated links to work done in a lower-division course.

The reporting of the critical events is where data from the DBIs provided the most insight into how student writers develop while at a university with a writing program that explicitly supports knowledge transfer. The examination of these critical events allowed the research team to argue for ways a writing program can support three distinct stages of a writer’s development. The critical events also provided insights into how a writing program with lower- and upper-division requirements can frame writing development in a way that supports the transfer of knowledge from one setting to the next. This set of the conclusions required the team to make a series of inferences across the various sets of data, inferences that would have been difficult to support were it not for the way our DBI protocol invited the participants to demonstrate the links they saw between learning objectives, instructor expectations, and their own writing.

The description of the fourth critical event is the clearest example of a DBI supporting inferences required to describe dynamic transfer at work. The upper-division participant had decided—on her own—to bring in a rhetorical analysis essay from her lower-division expository writing course. She also brought two writing samples from her most recent upper-division course. This choice prompted the interviewer to ask if the student used skills developed in the lower-division writing course when performing writing tasks in the upper-division course. The student reported that she did not believe the work done in the lower-division course informed work done for other writing tasks. The research team was able, however, to make connections across writing samples and the interview transcript to show ways in which the skills had in fact developed and changed across contexts. The rhetorical analysis the participant had brought demonstrated a developing understanding of rhetorical purpose and audience awareness. Those understandings were expressed in a new and more nuanced way when the student was asked about a patient case study composed for the upper-division writing course. The student’s answer drew sophisticated connections between her understanding of the intended audience and the purpose of a patient case study.

In this particular example, support for the theory we were investigating was bolstered by the research team’s decision to have students to select and analyze their own texts. The DBI protocol invited students to serve as quasi-researchers working along with the interviewer to better understand how writing develops over time in a university setting. This created support for an expansive set of inferences that showed the way prior knowledge develops over time through the use of social and environmental resources. The interview protocol was not able to show us everything that shaped and reshaped the understandings that students brought to the writing program. Much of what influenced the development of writers happens in other courses and in non-academic settings. The DBIs were, however, able to show ways students develop an understanding of programmatic learning outcomes over time.

Our research team’s experience with discourse-based interviews shows strong support for the ability of DBIs to collect data from dynamic learning environments. The interview technique collects the insights of a participant’s experience from both during and after the writing process. This allows for research into theories that seek to describe the problem-solving behaviors and learning processes associated with developing skills over the course of years. In cases where the theories being tested must contend with such a complex site, DBIs can utilize participant experience to facilitate inferences across a number of sources of data.

Appendix: Upper-Division Student Survey

Page 1: Survey Introduction

-

In which (calendar) year are you completing this survey? (2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016)

-

In which quarter are you completing this survey? (fall, winter, spring, summer)

-

Which writing course are you currently taking? (list of courses)

-

Year in school? (freshman, sophomore, junior, senior, graduate, not sure)

-

In which college(s) is/are your major(s)? (list of colleges, other, undecided/unsure)

Page 2: Writing and Language Background

-

When did you start at UC Davis? (as a freshman, as a transfer student, as a short-term study abroad student, as a graduate or professional student)

-

Have you taken the advanced writing examination at UC Davis? (yes and I passed it, no, I took it once and did not pass it, I took it twice and did not pass it, not sure)

-

Have you taken any other writing/English language classes at UC Davis? Check ALL that apply. (list of basic writing/ESL courses, list of first-year courses, list of upper-division courses, other, none)

-

Not counting the class you are in right now, when did you take your most recent writing class at (name of university)? (never, last quarter, within the last year, more than a year ago)

-

Have you taken any other writing classes NOT at UC Davis? (yes—please specify, no, not sure)

-

When you were a young child, how many languages were spoken by the adults in your home? (English only, English and one or more other languages, a language(s) other than English)

-

When you were a young child, which languages other than English were spoken in your home? Check ALL that apply. (none other than English, long list of language options)

-

Were you born in the U.S.? (yes, no)

-

Are you an international (visa) student? (no, yes--pursuing undergraduate degree, yes—short-term stay, yes—pursuing a graduate degree)

-

At what age/level did you first attend school in the U.S.? (preschool/kindergarten, Grades 1-3, Grades 4-6, middle school, high school, adult school, college/university)

-

At what age did you begin learning English? (from birth, 1-3 years old, 4-5 years old, 6-10 years old, 11-17 years old, 18+ years old, not sure)

-

Outside of school, what percentage of the time do you use English? (I speak only English, 76-100%, 51-75%, 26-49%, <25%)

Page 3: Your Writing Skills

-

Has writing (especially in school) been a good experience for you? Add comments if you would like to. (I always or usually enjoyed writing, I sometimes enjoyed writing, I rarely enjoyed writing, I never enjoyed writing)

-

Have you ever been given any specific feedback by teachers about your strengths or weaknesses as a writer? If so, what kinds of things did they mention? Answer ALL that apply.

-

No, not that I can remember.

-

Teachers generally liked my writing.

-

Teachers praised my content/ideas.

-

Teachers praised my organization.

-

Teachers praised my expression/language use.

-

Teachers felt my ideas were unclear or needed more detail.

-

Teachers criticized my organization.

-

Teachers criticized my language use (grammar, vocabulary, spelling, punctuation, or other mechanics)

-

Teachers never seemed to like anything about my writing.

-

Now we’d like to ask about specific writing goals and skills you have developed at college. Please complete the table below. For each skill listed, please check how comfortable/ confident you are with your writing ability in that area.

|

Skill |

Very comfortable |

Comfortable |

Uncomfortable / Not sure |

No opinion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Writing for a specific audience |

|

|

|

|

|

Planning and organizing an assigned paper |

|

|

|

|

|

Reading challenging academic texts |

|

|

|

|

|

Preparing for and taking a timed writing exam |

|

|

|

|

|

Choosing a specific research topic |

|

|

|

|

|

Conducting research on your topic |

|

|

|

|

|

Citing your sources appropriately |

|

|

|

|

|

Integrating evidence (i.e., quotations or data from sources) into your writing effectively) |

|

|

|

|

|

Avoiding plagiarism |

|

|

|

|

|

Working collaboratively on writing tasks |

|

|

|

|

|

Using technology to improve writing |

|

|

|

|

|

Giving feedback to others on their writing |

|

|

|

|

|

Using feedback from others to revise your writing |

|

|

|

|

|

Editing your writing to correct errors and improve language use |

|

|

|

|

|

Reflecting on your own writing progress |

|

|

|

|

-

Considering your responses to the previous question, to what extent do you think your previous college writing course(s) helped you to learn or improve those skills? (helped a lot, helped somewhat, did not help at all, not sure/no opinion, not applicable)

Works Cited

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. University Press of Colorado, 2008.

Berg, Bruce L., and Howard Lune. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 6th edition, Allyn & Bacon, 2007.

Bizzell, Patricia. Cognition, Convention, and Certainty. Cross-Talk in Comp Theory: A Reader, 2nd ed, edited by Victor Villaneuva, NCTE Press, 2003, pp. 387-411.

Brent, Doug. Crossing Boundaries: Co-op Students Relearning to Write. College Composition and Communication, vol. 63, no. 4, 2012, pp. 558-592.

Charters, Elizabeth. The Use of Think-Aloud Methods In Qualitative Research, An Introduction to Think-Aloud Methods. Brock Education Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, 2003, pp. 68-82.

Chen, Zhe, and David Klahr. All Other Things Being Equal: Acquisition and Transfer of The Control of Variables Strategy. Child Development, vol. 70, no. 5, 1999, pp. 1098-1120.

Creswell, John W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions, 1st edition. Sage, 1998.

DePalma, Michael-John, and Jeffrey M. Ringer. Toward a Theory of Adaptive Transfer: Expanding Disciplinary Discussions of ‘Transfer’ in Second-Language Writing and Composition Studies. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 20, no. 2, 2011, pp. 134-147.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn. Connected, Disconnected, or Uncertain: Student Attitudes about Future Writing Contexts and Perceptions of Transfer from First Year Writing to the Disciplines. Across the Disciplines, vol. 8, no. 2, 2011, pp. 1-36.

Emig, Janet. Writing as a Mode of Learning. College Composition and Communication, vol. 28, no. 2, 1977, pp. 122-8.

Engle, Randi A., Diane P. Lam, Xenia S. Meyer, and Sarah E. Nix. How Does Expansive Framing Promote Transfer? Several Proposed Explanations and a Research Agenda for Investigating Them. Educational Psychologist, vol. 47, no. 3, 2012, pp. 215-231.

Gick, Mary. L., and Keith. J. Holyoak. Analogical Problem Solving. Cognitive Psychology, vol. 12, no. 3, 1980, pp. 306-355.

Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Routledge, 2017.

Herrington, Anne J. Writing in Academic Settings: A Study of the Contexts for Writing in Two College Chemical Engineering Courses. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 19, no. 4, 1985, pp. 331-361.

Hayes, Hogan, Dana R. Ferris, and Carl Whithaus. Dynamic Transfer in First-year Writing and ‘Writing in the Disciplines’ Settings. Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer, edited by Jessie Moore & Chris. M. Anson. Parlor Press, 2016, pp. 181-213.

Huot, Brian. (Re)Articulating Writing Assessment for Teaching and Learning. University Press of Colorado, 2003.

Huot, Brian, and Michael M. Williamson. Rethinking Portfolios for Evaluating Writing. Situating Portfolios: Four Perspectives, edited by Kathleen Blake Yancey and Irwin Weiser. Utah State UP, 1997, pp. 43-56.

Inoue, Asao B. Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future. Parlor Press LLC, 2015.

Martin, Lee, and Daniel L. Schwartz. Conceptual Innovation and Transfer. International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change, 2nd edition, edited by Stella Vosniadou, Routledge, 2013, pp. 447-465.

Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Moss, Pamela A. Can There Be Validity without Reliability? Educational Researcher, vol. 23, no.2, 1994, pp. 5-12.

Odell, Lee, Dixie Goswami, and Anne Herrington. The Discourse-Based Interview: A Procedure for Exploring the Tacit Knowledge of Writers in Nonacademic Settings. Research on Writing: Principles and Methods, edited by Peter Mosenthal, Lynne Tamor, and Sean A. Walmsley, Longman, 1983, pp. 220-235.

Olson, Gary M., Susan A. Duffy, and Robert L. Mack. Thinking-Out-Loud as a Method for Studying Real-Time Comprehension Processes. New Methods in Reading Comprehension Research, edited by David E. Kieras and Marcel A. Just, Routledge, 1984, pp. 253-286.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. Knowledge To Go: A Motivational and Dispositional View of Transfer. Educational Psychologist, vol. 47, no.3, 2012, pp. 248-258.

Roozen, Kevin. Reflective Interviewing: Methodological Moves for Tracing Tacit Knowledge and Challenging Chronotopic Representations. A Rhetoric of Reflection, edited by Kathleen Blake Yancey, Utah State UP, 2016, pp. 250-267.

Thaiss, Christopher J., and Terry Myers Zawacki. Engaged Writers and Dynamic Disciplines: Research on the Academic Writing Life. Boynton/Cook, 2006.

Wardle, Elizabeth. ‘Mutt Genres’ and the Goal of FYC: Can We Help Students Write the Genres of the University? College Composition and Communication, vol. 60, no. 4, 2009, pp. 765-789.

Whithaus, Carl. Think Different/Think Differently: A Tale of Green Squiggly Lines or Evaluating Student Writing in Computer-Mediated Environments. Academic Writing: Special Multi-journal Issue of Enculturation, Academic Writing, CCC Online, Kairos, and The Writing Instructor on Electronic Publication. Summer,2002. https://wac.colostate.edu/aw/articles/whithaus2002/.

Wragg, Ted. An Introduction to Classroom Observation (Classic edition). Routledge, 2011.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. University Press of Colorado, 2014.

Participant Coding in Discourse-Based Interviews from Composition Forum 49 (Summer 2022)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/49/participant-coding.php

© Copyright 2022 Hogan Hayes and Carl Whithaus.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 49 table of contents.