Composition Forum 45, Fall 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/

Dissertation Boot Camps, Writing as a Doctoral Threshold Concept, and the Role of Extra-Disciplinary Writing Support

Abstract: This article seeks to answer two questions: what kinds of expertise are needed to lead an effective dissertation boot camp; and how can those outside the graduate student’s discipline support their writing? Drawing on four years of application data and post-camp interviews, I reveal how writing process knowledge—similar to that described in the scholarship on first-year composition—is a fundamental reason dissertators seek help from the boot camps. Ultimately, the article argues that the importance of writing as a dissertation-related threshold concept should be clearly stated and understood across all disciplines: doctoral researchers continue to learn and practice writing. As part of broadly accepting this threshold concept, it becomes clearer that those trained in writing pedagogy and its theories are best situated to lead the most helpful writing-process style boot camps.

Dissertation boot camps{1} are some of the more attractive kinds of programs a university can offer due to their relatively low stakes—they require few resources and few staff. The boot camps at University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), grew from the Graduate Division’s desire to better support graduate writing. As one prong of their efforts, I first developed a series of half-day workshops for humanities graduate students, with an emphasis on three separate stages of their school writing life: writing the seminar paper, writing the prospectus, and writing the dissertation. In the evaluations, a participant specifically requested a dissertation boot camp, like those in which friends at other universities had participated. In researching my proposal in 2013, I found there was little scholarship on best practices for structure and pedagogy. The most robust pedagogical information, perhaps even to this day, was from the UNC Chapel Hill Dissertation Boot Camp Resources website that includes handouts for workshops and materials on typical dissertator concerns like managing writing groups and formatting the final product.

Scholarship on these boot camps is now beginning to describe some best practices, and this article contributes to the trend by examining dissertator boot camp experiences and what was most helpful. Data stem from a four-year study of UCSB’s boot camp offerings, reporting what applicants feel is lacking in terms of the general writing support at the university, what they hoped to gain from the camp, and what participants remembered nine to twelve months post-camp as being the most helpful. Results indicate these dissertators largely identify a consistent set of writing-related issues with completing the dissertation and it appears the most helpful boot camp pedagogy emphasizes particularly the importance and struggle with writing process-related tasks, like planning, reviewing, and maintaining accountability structures. This data is valuable because it can help us consider two questions yet to be covered in the dissertation boot camp scholarship: (1) what kinds of expertise are needed to lead the most effective dissertation boot camp? And (2) since graduate student writing is rooted so firmly in the home discipline, how can those outside the discipline support it?

First, I will cover the origins of the dissertation boot camp and the relevant scholarship that has thus far investigated these offerings. I then view graduate student writing through the lens of first-year composition (FYC) notions about writing and how there are some broad similarities between first-year college students and dissertators that help us to understand why the dissertation is such a location for struggle. Next, I report on the data and connect the findings on writing process-related help to conceptual learning thresholds so we can turn, finally, to how writing is a fundamental, troublesome activity in the dissertation process and should be recognized as such with its own threshold concept. With that in hand, this data and these connections then suggest writing faculty/those trained in writing pedagogy and theory as positively supporting these students despite being outside of the dissertators’ disciplines.

Understanding the Dissertation Boot Camp

At its most basic, a dissertation boot camp is a type of writing retreat specifically aimed at graduate students writing their doctoral dissertation or, in some cases, their masters’ thesis. “Dissertation boot camp” is the most commonly used term for these programs across the US and perhaps the world, but some institutions aim to avoid militaristic language. Thus, the program can also be called a Write-in, a Writing Retreat, a Dissertation Camp, or similar. In terms of structure, two models form the basis of most dissertation boot camps: “Just Write” and “Writing Process” (Lee and Golde 2). The “Just Write” model works on the assumption that if students are given a good space, food and coffee, and some time to write, then they will be productive. While the emphasis is on production, these types of boot camps may offer short workshops on typical dissertation-related problems. Alternatively, the “Writing Process” model includes both the space and time to write as well as fairly intensive conversations about writing, either in group workshops and/or via one-on-one consultations. Consultations can be with faculty in the student’s discipline, faculty from composition & rhetoric, or writing center staff.

These programs are still in their relative infancy, having only come to the fore in the last 15 years or so. One of the earliest documented examples was in 2005 when the University of Pennsylvania offered their dissertation boot camp, a 2-week summer session meeting daily for 4 hours, comprising primarily locked-door writing time for the attendees (Walker). The first camp was limited to 20 students, but the program was so popular it was offered twice more in that 2005-2006 academic year. In 2007, 3 other universities—Yale, University of Kentucky, and UCLA—launched their own camps. The number of universities throughout the country with dissertation boot camps has multiplied: a Google search yields so many results in the United States alone, the better question might be who is not offering a dissertation boot camp at this time.

In terms of scholarly publications on these boot camps, what exists generally explores three themes, though there are overlapping aspects between all three. The first theme encompasses publications that primarily serve as practical guides for designing a boot camp and broadly articulate different pedagogical possibilities (Allen; Havert; Lee and Golde; Mastroieni and Cheung; Powers). With the second theme are articles that consider boot camps within the graduate writing support context as a whole. There, scholars do include some practical guidelines, yet these works emphasize the efficacy of such limited programs, especially if they are the sole option for writing help. Steve Simpson argues that these kinds of retreats should be offered with an outward orientation, where faculty from writing and all the disciplines create several programs together, thereby broadly supporting grad writers (Simpson, Building; Simpson, Problem). Many universities may skew to offering only a dissertation boot camp and believing that the work of supporting graduate student writers ends there, which is Doreen Starke-Meyerring’s concern: the retreats in some instances function merely as a band-aid on the larger problem because they position writing as a remediable skill that can be fixed by a single workshop or retreat (83).

The third strain of scholarship again considers the practicalities of the boot camps, but their main focus rests in how and why they are helpful in and of themselves. Much of the data gathered in this theme revolve around student experiences in the boot camps and how any aspect of their writing or attitudes towards writing changed after participating. For the attitudes towards writing, Uta Papen and Virginie Thériault found that dissertation boot camps and writing retreats were excellent ways for students to positively self-reflect on their writing experiences and the emotions they attach to the PhD process. Gretchen Busl et al. noted changes in approaches to writing as they measured confidence levels and self-regulation in dissertators before and after a dissertation boot camp. They found that process-oriented camps—that is, those that emphasize writing process—do provide some improvement in post-camp writing behaviors. Similarly, Ashley Bender Smith et al. interviewed participants in one boot camp both before and after the program. These scholars found that dissertators had more agency in their identity as writers, considered writing processes differently, and established a supportive community within the camp that they extended into their post-camp writing lives. It is within this final scholarship theme that we may begin to understand the kinds of writing knowledge needed to effectively lead the dissertation boot camp. Graduate writing help is troublesome because so much of the work is rooted deeply in writing in the discipline—something that a writing pedagogy expert may not be able to help with. Yet, what if there are aspects to the dissertation writing process that could be and, perhaps, are best covered by someone trained in writing pedagogy? One important way writing pedagogy has implanted in the university is via FYC programs and turning to FYC scholarship does yield some possible connections between undergraduate and graduate writers, though of course at very different levels.

Some Connections Between FYC and Dissertation Writers

When first thinking about graduate student writing and the pedagogy for the boot camp, I was struck by some of the similarities between the graduate students I encounter and FYC students that writing studies scholars like Nancy Sommers, Laura Saltz, and Anne Beaufort describe. One way of understanding how new college students struggle with their writing is via the concepts of writing learning thresholds. Sommers and Saltz have theorized that FYC students cross learning thresholds by “writing into expertise” (134). The thresholds FYC students must cross include navigating and forming some sort of new identity; going through a liminal phase with multiple conceptual learning thresholds; and moving from novice to expert via writing.

In terms of connections to graduate students and dissertators, extant scholarship considers the very same thresholds. For navigating and forming a new identity, graduate students via the dissertation process are, essentially, forming a professional identity. How this is theorized in higher education literature is usually attached to concepts of socialization: how the graduate student becomes a professional in the field by socializing into their discipline (Austin; Gardner et al.; McAlpine et al.; Sundstrom; Weidman et al.). For the second threshold on liminality, this, too, is a focus of research on graduate students, again often related to creating a professional identity (Deegan and Hill; Keefer; Winstone and Moore). The final threshold, however, moving from novice to expert via writing is not as easily discerned in the scholarship on graduate student writing.

To better understand how Sommers and Saltz’s threshold on writing into expertise might apply to dissertators, I turn to Beaufort’s work with undergraduate writers. She notes that FYC writers move from novice to expert in a particular discourse community by moving through five common knowledge domains: subject matter knowledge, genre knowledge, rhetorical knowledge, discourse community knowledge, and writing process knowledge (17). When considering the first four domains, we can see how those might be strongly lodged in the discipline, requiring the dissertation committee members to help navigate any issues. Writing process knowledge, however, sounds quite similar to the writing process concerns—things like motivation, avoiding procrastination, and setting up accountability structures—boot camp participants find most troublesome. Zeroing in on Beaufort’s description for writing process knowledge demonstrates the overlap, where she notes it comprises “knowledge of the ways in which one proceeds through the writing task in its various phases”—what she also calls “procedural knowledge”—as well as things like knowing when and where to begin, what drafting strategies to use, and what to do with outside information (Beaufort 20). By synthesizing Beaufort’s FYC procedural knowledge and the types of procedural knowledge boot camp participants find most useful as described above, it suggests a space in which those trained in writing pedagogy would be well situated to help.

Data from my study confirms these findings on the pervasive importance of writing process concerns, and their mitigation, to the dissertators. It is also the foundation upon which we can then determine not only who is best situated to lead the dissertation boot camp from a pedagogical perspective, but also how and why an extradisciplinary leader may be an excellent choice for alleviating the concerns in this particular domain.

The Current Study

In order to assess what students hoped to gain from dissertation boot camps and what they felt was most useful in the longer term, I use two IRB-approved data sources: application question data (2015-2018), which includes some information about what students are looking for as they apply for the boot camp (n=213); and interviews nine to twelve months post-camp.

UCSB, an R-1 institution, is largely undergraduate-focused with their enrollment some 5x the number of graduate students at the university. As of 2018-19, the graduate student population here was approximately 2900 students total. Programs available to these graduate students are largely academic-focused, with master’s degrees offered in most academic disciplines (MA, M.Ed., MM, MS, and MTM) and terminal academic degrees in some 50 disciplines (DMA, MFA, PhD). Also, the Education and Counseling departments offer several degrees involved with teaching and therapeutic practice. In terms of how students are filtered across the metadisciplines, approximately 10% are in the Education division, 30% in the Engineering/Computer Science fields, 15% in Humanities/Arts, 30% in the Physical/Biological Sciences, and 10% in Social/Cultural Studies (BAP profile; numbers are inexact due to approximation and don’t add up to 100%). Central administration for graduate students is lodged in the Graduate Division, which oversees many aspects of applications and process-to-degree checks, as well as being an intermediary for any department-student issues.

As at many other schools, graduate communication support is somewhat scattered across the institution (Caplan and Cox 23). First it is important to note, though it is a possibility for graduate student use, the on-campus writing center is staffed by undergraduate writers and, thus, it is not seen as a real resource for graduate writing support. Some departments offer dissertation writing seminars, classes where dissertators peer review each other’s work, but their ability to be offered and their anecdotally-reported quality is wholly dependent on the faculty who choose to teach them. The Graduate Division for many years has employed Graduate Writing Peers, part-time paid positions usually filled by a writing studies graduate student who offer one-on-one consultations as well as short workshops (typically two or three hours in length) on writing concerns ranging from cover letters and CVs to the dissertation prospectus to the job talk. In recent years the Graduate Division also secured a Graduate Writing Room, where for several hours each week writers can go for some quiet space that also has coffee and other amenities. Most recently, UCSB created a position dedicated solely to graduate writing and, in doing so, hired a PhD trained in and experienced with graduate writing centers who is both expanding the program and reaching out across departments to better unite the fragmented offerings.

The dissertation boot camp, first offered in 2014, has been led by the same Writing Program faculty member (me) for each iteration. It was offered once per summer in each of 2015 and 2016. In 2017, though, the program was expanded to two boot camps per summer—one just after the school year ends and one just before school starts in the fall. The dissertation boot camp is co-sponsored by the Graduate Division and the Summer School, and is limited to twenty participants total, except the pilot in 2014 that was limited to ten. That 2014 pilot included only doctoral students from humanities and social sciences disciplines, but all subsequent offerings were available to doctoral students from all divisions. UCSB’s dissertation boot camp runs for four, six-hour days. Writing time comprises three hours minimum per day, with opportunities to write for a further thirty minutes via some flexible options in the late afternoon. A typical schedule involves a morning goal-setting and check-in session for fifteen minutes followed by a ninety-minute writing block. After a brief break, a writing workshop fills the time before lunch: workshops are on topics like goal setting and task breakdowns, writing to digest difficult ideas or texts, understanding and overcoming procrastination, maintaining momentum, and revision strategies for longer works. After lunch, participants immediately begin the afternoon ninety-minute writing block. Following the final short break, participants can either continue writing or have the option for small-group informal debriefs in the common meeting room or one-on-one consultations with the graduate writing peer/specialist or the boot camp leader. Each day closes with a fifteen-minute logging session, a brief metacognitive reflection on the day’s activities, and some time planning the next day’s tasks.

Application Data

For the application data, beginning in the 2015 application process—the second, at the time, annual offering—prospective participants answer a series of questions, including information on their dissertation project and how many chapters have been accepted/completed thus far. Personnel in the Graduate Division, in consultation with me, created these application questions in order to assess who might be best situated to participate in the boot camp. For example, a dissertator who is at the very end of the process, madly revising and formatting, is not an ideal candidate for the writing-process style boot camp offered here.

Two questions from the application data give us some broad-based information on expectations and desires these students have for making progress on their dissertation and identifying what issues they would like help with during the boot camp. In the two questions, applicants are asked (1) what has caused their dissertation trouble, and (2) to choose from a list of obstacles or issues that impede progress on the dissertation, with an option to enter their own (see Appendix 1). UCSB’s IRB approved coding only those question responses.

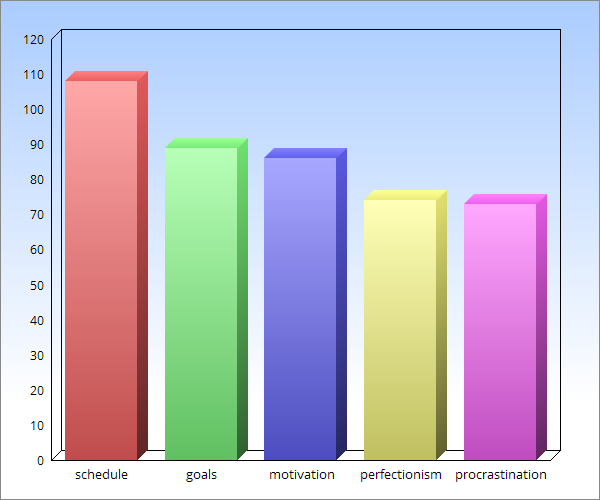

Figure 1. Top Five Writing Issues in Boot Camp Applications

In the six offerings from 2015-18, the top five issues in order (see Figure 1) were making and sticking to a schedule (n=108), setting and meeting goals/deadlines (n=89), staying motivated (n=86), overcoming perfectionist tendencies (n=74), and overcoming procrastination (n=73). When students chose to include a clear ranking of these items (n=82) the item most often listed as the primary issue was setting and meeting goals/deadlines (n=18) followed by making and sticking to a schedule (n=14) and overcoming procrastination (n=10). The applicants are guided to an extent on how to answer this question, but the form still allows for free answers. Freeform answers were coded as well and, even when using their own words, students still identified the same issues.

While the students do have the option to mention specific disciplinary concerns as well as issues with their advisor(s) or committee members, what is striking is how many prospective participants are really seeking help with this procedural knowledge I mention above from Beaufort’s work with FYC students. This indicates that at UCSB students seeking out a dissertation boot camp are feeling unstable due to a lack of knowledge or success at going about their writing tasks. The post-camp interview results also indicate similar concerns, though there is one notable difference.

Post-boot camp interview results

For the IRB-approved interviews, participants from each boot camp were invited approximately nine to twelve months afterward to answer some questions at in-person semi-structured interviews. Thirty-eight participants responded, a 43% response rate as of December 2018, which includes 2014-2017 participants (five boot camps). The interviews took place at UCSB and lasted approximately twenty to thirty minutes. Participants were asked why they signed up for the boot camp, what they felt had impeded their progress on the dissertation, if anything, and if they had changed anything about their dissertation habits after the retreat. With the interview transcripts, I created line-by-line coding and categories on the responses to four of the questions (all questions are available in Appendix 2): A3. how would you describe the trouble, if any, that you had with the dissertation? B1. What motivated you to sign up for the dissertation boot camp? B2. What did you accomplish during the retreat? B3. What tools and techniques did you find most beneficial? Least helpful? The categories coded are as follows:

- Accountability

- Ambiguity

-

Ambiguous measures of good

productivity

- Dissertation genre

- Expectations from advisor

- Unpredictability of time on a task

- Disciplinary issues (those that advisor needs to answer)

- Goal Setting/Planning

- Metacognitive writing

- Motivation

-

Personal writing process

- time awareness

- emotional awareness

- writing-to-learn

-

Procrastination

- Perfectionism

- Inability to start writing

- Task Management

-

Time Management

- Taking too long (task or general)

-

Writing Process

- Organization

- Prioritizing tasks

- Reading vs writing

- Revision

- Support system missing

- Work-life balance

All coding analyses were conducted in Dedoose qualitative analysis software. The breakdown of metadisciplines in the interviewees were eleven Humanities, ten Social Sciences, six Humanistic Social Sciences, six Formal Sciences, and five Natural Sciences.

For the interviewees, the issues coded for most often included time management and accountability/structure.

Time Management, Goal Setting, and Accountability

The most frequent code in the interviews for reflecting on what was most helpful was related to time management and goal setting (n=33 or ~87%). Note here that scheduling and goal setting were two separate issues in the application data. I keep them discrete because, while they do overlap, time management and scheduling is more of a micro or near-term concern whereas setting and achieving goals operates more as a macro or longer-term issue. They are combined here with the interviews because the interviewees themselves often juxtaposed them during the conversation.

Needing to create their own structure was a typical stumbling block for day-to-day dissertation progress. One humanistic social sciences participant encapsulated the competing time pressures perfectly:

“It’s both about having an endless amount of time and never enough time.”

He subsequently clarified:

“I think that’s probably the biggest issue: feeling like when I’m not working on it, and I step away to do something else, you get that pressure where you should be working on it. And when you are working on it, there’s a sense that you never make enough progress because it’s not all done and you’re not writing 20 pages in a day. So that makes it hard sometimes and you get writer’s block sometimes. And you spend an entire day trying to pound out that paragraph or two as opposed to going back to primary texts or something else.”

Moving to the longer-term aspect of time management, goal setting and practice with project management ends up being particularly memorable for some participants. Being able to identify what is needed to complete a chapter, or even a section, and how to schedule that out is a key skill that will help them if they continue in academia, where they must balance teaching, research, and service. Beyond just how much time per day of writing works for them, another common awareness that can arise is how to structure their writing to make measurable progress. A social sciences respondent noted:

I remember the first day when it was get our task lists together and put them on the wall. I remember feeling like ‘crap I don’t know what tasks, I mean I know what chapter I want to get done.’ But, when you started talking about how to break down the tasks, I struggled with it. It really brought to light that I don’t really know how to do that. I’ve only seen these chapters as these amorphous wholes and I don’t know how to segment it up to say ‘here are the finishable [tasks], able to be completed areas that if I do ABCD and E, then I’m left with something larger.’ It helped me think about how I was writing differently.

Some of the trouble these students encounter is also a sense of being unsure: unsure what they should be doing when, unsure how much progress they should be making on any one day, and unsure how to harness this huge, sometimes multi-year, project. These are all part and parcel of that procedural knowledge Beaufort notes in the writing process domain that FYC writers must work through and, essentially, the dissertators are encountering a relatively new writing situation—much like those FYC students.

Procedural issues continue to loom large with the next-highest code, accountability, since this is often the first-time dissertators lack externally-enforced deadlines. Eighteen of the thirty-eight (~47%) interviewees indicated that the accountability and structure of the boot camp was beneficial for them in the long run.

One social sciences participant noted,

I’ve been productive in…knowledge gathering, but not as productive in producing. I really needed to take these…like sections that I have to have the time and the space that I can just focus on, where even though there’s no real penalties, I feel that I will be held accountable for it. And that kind of made all the difference.

This issue is one of the tools dissertators need to learn or highly develop in order to succeed: remaining productive and intrinsically motivated. One way to think about it is that, until this point, graduate students’ schooling experience has been driven largely by external accountability and penalties for work undone: due dates and ends of terms have provided a rhythm that suffuses every aspect of their school work. Writing the dissertation may be the first time these students encounter a school world in which the deadlines are not hard and fast. In fact, some of the more productive post boot-camp participants developed their own external accountability structures after realizing their importance, even if the accountability within the boot camp wasn’t a good fit for their particular style.

A humanities participant spoke to this exact issue:

I think the way [accountability] worked in the retreat, it didn’t work for me. But it encouraged me to think about it and how I was going to have accountability for myself and my writing. I had a friend who was also working on writing her dissertation from [another continent] and we met, she was here for a while. We both work on similar things, similar enough that we cannot be in competition and offer useful and helpful feedback. She was my first reader of everything. We would Skype every 2 weeks and talk about whatever stuff we were working on. Send whatever version of a chapter, she would read my stuff and I would read her stuff. So, I had that peer feedback.

What we see in these interviews are students who didn’t realize how important these external deadlines and accountability structures were for them. This lack of experience with a writing context seems to create a sense of destabilization where some—though not all—dissertators struggle to make progress because they simply do not know what to do or what strategies work for them.

Lack of progress is evident to some extent in the interviews with some noting how the retreat made them aware of strategies they’d either never used or heard of before or, in some cases, had forgotten about. One humanities interviewee noted a difference between the kinds of writing procedures she’d used before and what was happening with the dissertation:

[My writing time], it was very deadline-driven and not paced out, but it was a different kind of pressure and routine than what I did for seminar papers when I was taking courses. You almost have to do writing in big chunks because you don’t have the knowledge yet at the beginning of the quarter to write papers so there were those, again, deadline-driven writing practices that were very focused on small parts, whatever the seminar was on. So, it seemed like I was carrying on those practices into the dissertation writing and I knew that wasn’t gonna work for me. But, I didn’t know what worked for me because I hadn’t really done anything else. And the writer’s retreat really gave me the opportunity to explore what those other routines might look like. And it revealed that my writing style was not what I thought it would be and when would be most convenient for me. But I figured if I’m going to do this and do it well, let me try this new routine that requires more effort on my part to carve out the time on a daily basis, but hopefully will allow me to be more productive. (emphasis mine)

This student essentially attempted to repurpose writing strategies from one context to another, but struggled because, as she notes, she didn’t know what would work for her and didn’t feel like she had the room to explore this procedural knowledge, for whatever reason.

Procedural knowledge is dealt with in Beaufort’s writing process knowledge domain, but “repurposing” older writing process knowledge has been studied elsewhere in the composition and rhetoric realm. Those works emphasizing adult and graduate student learners appear as if they might apply here. Kevin Roozen’s case study of master’s-level graduate student Lindsey reveals a writer who adapts to new or troublesome writing situations by applying prior knowledge to her current work. She was able to write into master’s-level expertise precisely because of her flexibility and creativity in cross-applying writing process knowledge. Similarly, Michael Michaud performed a case study on one returning undergraduate adult student, Tony, to consider the ways in which this student transitioned from a professional to an academic writing context. Tony largely practiced assemblage or remixing to compose in both writing contexts, again a means by which one can repurpose older knowledge to a new situation. Another study by Michelle Navarre Cleary also follows returning adult undergraduate students and how they apply writing process knowledge across professional and academic contexts. Those who appeared to have more facility with academic writing also tended to work in contexts where their writing processes were similar and the cross-application was, therefore, more seamless. Dissertation boot camp participants in this study, however, often noted that what worked before no longer does and, since none of the studies above deal specifically with dissertation writers, it is a likely reason that their writing troubles are not solved in the same way.

We know, then, that the dissertators struggle, but the data also indicate that the boot camp offered an opportunity to become aware of the struggle and, in some cases, to change or try on new writing processes. This leads us to the final highest code incidence, which was personal writing process.

Personal Writing Process

Personal writing process coded responses appeared in fifteen of the thirty-eight respondees (~39%) indicating it was something they developed or learned about in the boot camp. For an excerpt to qualify as a “personal writing process” code, the dissertator needed to impart some level of awareness of or change to how they approach their writing and writing process outside of the boot camp to make them more productive in the long run. Subcodes for this involved an awareness of how to use their writing time, awareness of how their emotions affect their writing, and awareness of writing-to-learn.

Time Awareness

For time awareness of writing process or writing issues that would help them after the camp was over, the most common was related to the amount of writing time per day that maintained productivity after the boot camp. Too often, conventional wisdom teaches us to treat writing the dissertation like a day job—writing from 8 am to 5 pm—but for most dissertators, writing for seven+ hours per day is likely impossible to maintain over months or years. Even so, many of the participants begin the program expecting to write an entire chapter in the course of one week. Several of the interviewees experienced a shift in their understanding of what a “good” writing day looks like for themselves.

A formal sciences participant articulated a typical response:

I learned that a three- to four-hour day is a whopper. If I was going to have any semblance of a pleasurable life for the rest of my graduate career, I should not aim to do more than two to three hours on my dissertation, which was totally a feasible thing. But, for my mood management, okay three is a super solid day. One is even a good day, don’t get down on yourself that you’re not doing four every day as that is just not feasible.

This kind of time awareness is important over the long term with project management because it helps the student identify approximately what amount of writing is enough to maintain a more consistent writing schedule, as opposed to spikes in productivity followed by procrastination.

Emotional Awareness

Emotional awareness-coded incidences corresponded to how people’s emotions or psychological responses affected their work on the dissertation and how they became aware of them during the boot camp. In our program, we spend an entire workshop on procrastination and identifying the reasons it occurs and some strategies for how to work through specific fears or concerns that lead to procrastination. Even a recent New York Times article emphasizes that procrastination is more about emotions and mood management than anything else (Liebermann). In our society where we value productivity above all, understanding the possible roots of not moving forward and being able to name it can be an important step in mediating its influences.

One natural sciences participant noted, “I also really liked the discussion about procrastination. It was really good to realize that I was likely procrastinating because I was afraid of finishing, not just being lazy.” This sense of being lazy versus being afraid of finishing is an important realization: if the graduate student is looking at a lot of school debt and/or a poor job market for their field, it can be debilitating when trying to overcome procrastination tendencies. And managing procrastination is one of the more difficult procedural-knowledge type skills dissertators encounter and come to terms with.

Writing-to-learn

When dissertators realized that writing was a tool for assimilation or came to some understanding about their topic, or even themselves as writers, the excerpt was coded as writing-to-learn. Akin in some ways to the writing-to-learn activities in WAC classrooms, these lessons included uncovering how pre-writing helps overcome trouble beginning the writing day or learning that they can shape their understanding of difficult materials via writing.

A humanities participant noted:

When I came to you and said I was struggling with the structure and how to present things, you told me to just write, write, write, and not to have an impediment on the creativity. And that really helped. I started writing, writing, writing. And I discovered—well, I knew, but it became more apparent and vivid—that through writing your creativity and new thoughts and ideas come up. It was a very important awareness.

A greater understanding of working and writing through failures to write for graduate students has received some attention elsewhere as being a common aspect of writing development. Gina Wisker and Maggi Savin-Baden consider these writing “stuck places” as preliminal—that is, a state “before the development of successful modes of writing” (235). Preliminality, they argue, is related to ontological insecurity where a graduate student feels insecure about her place in the world (241). To break through, and move to the liminal and then into “focused, formed writing,” Wisker and Savin-Baden found that the most successful were those who moved on, practiced patchwriting, valued preliminality, and envisioned movement through a portal (242). Alternatively, E. Marcia Johnson notes that these stuck places are common for dissertators, resulting in two threshold concepts: “talking to think” and “self-efficacy” (239). Having trouble, then, might be a prevalent aspect of the dissertation writing process, and the boot camp may be providing an important set of experiences where students can practice and think about their writerly strategies and, more importantly, these difficulties are normalized for them. All of this, but especially feeling normal, appears an important aspect of alleviating these writing process concerns. Indeed, one humanities student noted, “The most helpful was talking with other people and knowing that other people are struggling ... That I’m normal. That those other people in my department trying to save face? They’re abnormal.”

A sense of awareness and normality is exactly what Christine Casanave discusses when she notes that dissertators must “display the expertise of scholars”—that is, they “must display more expertise than they currently embody”—even as their supervisors may also lack expertise in the dissertation genre and in dissertation advising, so they, too, are in the midst of performing expertise (58). The idea of a performance-in-tandem appears especially disconcerting in light of Anthony Paré noting that the supervisor-student dyad is a most crucial educational relationship because it is where scholars are initiated into the process of making new disciplinary knowledge via writing (59). Casanave surmises that the best solution for students is awareness: “Awareness that these performances are a normal part of an academic life can help prevent the debilitating anxiety that comes from expectations that are set unrealistically high” (57). And that anxiety is often manifested by lack of progress on the dissertation, which ultimately leads to the “stuck places.”

***

Considering the interviews together with the application data, we can trace what issues remained important both before and after the boot camp as well as any new awareness that arose post camp. Procrastination, time management, and goal setting emerged as the most difficult for dissertators to overcome, both pre- and post-camp. These three common issues are certainly not fixed via a one-week program and the writer’s experiences with them likely change over time—reasons for procrastination, for example, will shift during a multi-year dissertation process—which also indicates why they remain as post-camp concerns.

Post-camp interviews saw a different emphasis on two issues, however, in comparison to pre-camp data: accountability and personal writing process. Accountability is most emphasized in the post-camp data. Few, if any, of the applicants mentioned accountability, but the prevalence of this concept in the interviews is striking. Students may not realize its significance until they are told where to be and when to write for a week. Determining what kind of accountability structures work for them also shows that the boot camp is a means by which dissertation writers can reorient their writing habits or introduce new habits in order to determine what is most helpful for them. After accountability, personal writing process was the second highest post-camp code incidence, which could imply this new focus on their writing habits came about due to the boot camp program. During the boot camp, participants are required to engage more deeply with writing process-related items like keeping a consistent schedule or writing into the day as well as identifying the emotions that affect their productivity. All of this, but especially the pre- and post-camp comparisons, situates the boot camp as providing important realizations for the students.

Knowing what factors are important to the graduate students is pivotal in terms of programmatic and pedagogical issues and, subsequently, understanding how boot camps can help writers. Yet, the question still remains as to who is best situated to benefit the most participants. Is it only those in the dissertator’s discipline, since they have the best knowledge of the content and writing conventions for that field? Can it be anyone? Should it be someone trained in writing pedagogy?

Who is Best Situated to Lead an Effective Boot Camp?

It may seem like any competent, experienced writer could effectively lead a writing-process based boot camp, but the two problems with that reasoning are the disciplinary nature of the dissertation and the high level of writing these students must produce. A similar troublesome tension existed in who should teach FYC versus writing-intensive courses and how the qualifications for teaching each are different. One argument clearly articulated that FYC courses merited having an instructor who is not just a competent writer (though very knowledgeable in their discipline) but also well versed in the “theoretical issues that undergird writing instruction” (Chapman 56-57). Understanding that there is a need for this kind of training in theory and pedagogy is something that we can, and should, bring to our approach to graduate student writing because of how and why boot camps benefit the participants. But, the case is even stronger in light of this idea of conceptual thresholds that has seen a major focus in FYC literature and some attention as well in the scholarship on graduate communication.

As noted above, Sommers and Saltz specifically surmise that undergraduates in FYC pass through learning thresholds. Threshold concepts in learning were first articulated in 2005 by Jan Meyer and Ray Land. At its core, a threshold concept is like a “portal” that opens a new, previously unknown, way of thinking about something. With this new understanding, the learner is transformed. Land, Meyer, and Caroline Baillie note that threshold concepts are “transformative (occasioning a significant shift in perception), integrative (exposing the previously hidden inter-relatedness of something), and likely to be, in varying degrees, irreversible (unlikely to be forgotten or unlearned only through considerable effort), and frequently troublesome for a variety of reasons” (ix).

Threshold concepts for those pursuing graduate-level research degrees have been written about fairly extensively in recent years by Margaret Kiley and Gina Wisker. There, these scholars suggested that there are some “generic doctoral-level threshold concepts” as opposed to the discipline-specific type typically seen in the research: argument, theorizing, framework, knowledge creation, analysis and interpretation, and research paradigm. Further via their study, Kiley and Wisker described four threshold concepts useful in identifying if someone is “working at the level appropriate for graduate research: questioning and problematizing of accepted concepts; being able to mount a defensible argument; [developing a] conceptual and theoretical framework; and developing questions, design, data analysis, conclusions—so that conceptual and theoretical conclusions will be produced” (439-40). Those trained in writing pedagogy understand that writing in all its forms suffuses each of the six general and four more specific thresholds, even as writing is not explicitly mentioned in any of the concepts. Returning to the Wisker and Savin-Baden work mentioned above, these scholars connected certain types of writing practices—busy work, reading to write, mimicry, and patch writing—to how doctoral writers overcome the “stuck places” encountered in a liminal phase before crossing a conceptual threshold (238). They emphasize the liminal phase and how doctoral students can lever themselves through the threshold concept’s portal via writing—how writing is a means to a disciplinary end.

Yet, the data seems to emphasize writing as a source of its own set of troubles, as a thing unto itself as opposed to a means of moving through the liminal phase on a disciplinary concept. Writing is also the thread that unites the doctoral conceptual thresholds identified above. I suggest, then, that we should pay heed to writing’s essential importance in the dissertation process by adding a general doctoral research threshold concept on writing. Doing so would help further tear down the notion that doctoral students already know how to write, as discussed by Marilee Brooks-Gillies et al. Moreover, it would acknowledge writing’s function as a fundamental act for dissertators, as well as a fundamental place of trouble for many.

To uncover what this dissertation writing threshold might look like, I turn to some threshold concepts from writing studies—the very discipline whose concepts undergird FYC writing about writing courses—that could explain the portals graduate student writers must move through in their doctoral dissertation journey. In writing studies, one meta-threshold—that is, one that covers many sub-concepts—is that “all writers have more to learn” (Rose, 59). Also under this umbrella would be concepts of writing like “failure can be an important part of writing development” (Brooke and Carr, 62), and, especially cogent to what our data show, “learning to write effectively requires different kinds of practice, time and effort” (Yancey, 64). Though these are thresholds situated within a specific discipline, borrowing it for our general doctoral concepts is, in some ways, similar to how an FYC course based on these same concepts introduces students to the discourse at the university. In light of the intriguing connections between first-year college students and dissertators outlined above, these similarities lie at the heart of my argument for how to state the dissertation writing process threshold concept.

Indeed, simply adding a riff on the umbrella concept that “all writers have more to learn” to the doctoral research conceptual thresholds would pay heed to the important, and very frustrating place, writing has in the lives of dissertators. Thus, the new concept could be stated as “doctoral researchers continue to learn and practice writing.”

Once we unequivocally recognize that doctoral researchers must continue to learn and practice writing, the answer to who should lead the boot camp is clearer. One argument is always that those in the dissertator’s discipline are best, which could be true in some cases. Studies show, however, that many find it difficult to articulate the norms and conventions of their fields—that the most effective dissertation advisors were those who co-wrote, essentially, with their advisees (Paré et al). I argue that the people best situated to aid with writing process concerns would be those who have training in the theories that inform writing pedagogy and have translated these theories into effective practice. While these backgrounds may not help with the technical, disciplinary side of the dissertations, their theory-driven knowledge and practical experiences with writing and drafting procedures, as well as task management, can be shared with boot camp participants of any discipline. Ideally, the leader would be someone who is teaching in one of those fields, or leading a writing center at the university, with a background comprising extensive experience or schooling up through a PhD in one of those comp-rhet and related fields. Another good candidate could be a late-stage graduate student who has taught FYC, has been exposed to the theories behind these pedagogies, and would feel comfortable not only teaching the higher-level procedural knowledge needed for the dissertation, but also leading as a colleague and one who has yet to finish. In this particular instance, the graduate student’s work could be augmented by having one-on-one consultations with writing program or writing center faculty. These are not the only kinds of people who would be most advantageous to lead a boot camp, but it is important to understand the level of writing process teaching experience and theoretical background the facilitator has before endeavoring to lead a writing-process oriented boot camp—the most helpful of the boot camp styles.

Our new doctoral threshold that writing is a fundamental aspect of the dissertator’s experience, and that doctoral writers continue to practice and learn about writing, is very familiar to those best suited to lead the boot camps. Nevertheless, stating it outright and digging into the data on what students expect and receive from a boot camp reveals important ways writing pedagogy and theory can help dissertators across the university. Adding the writing threshold concept also helps better explain how and why someone outside of the discipline can be of help—indeed, in some cases extra-disciplinary feedback on writing is called for, depending on the nature of the dissertator’s trouble. Much like we saw with FYC, writing studies and related disciplines have much to offer dissertators and its practitioners should be the first consideration when planning a boot camp offering.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Application Questions*

Please indicate which of these issues you would like help with:

-

Setting and meeting goals/deadlines

-

Overcoming procrastination

-

Getting feedback from my advisor

-

Overcoming perfectionist tendencies

-

Avoiding and overcoming writer’s block

-

Staying motivated

-

Making and sticking to a schedule for writing

-

Revising and editing skills

-

Forming a writing support group

-

Other/enter your own

From that list of issues, what do you see as the 3 or 4 with which you need the most help?

*these are the only 2 questions approved for coding by UCSB’s IRB board.

Appendix 2: Interview Questions

-

Interviewee Background

-

In what year of graduate school are you at UCSB? Alternatively, how long after the boot camp did you complete the dissertation?

-

What is your home department?

-

How would you characterize or describe the trouble, if any, that you had with your dissertation?

-

-

Boot Camp Experience

-

What motivated you to sign up for the dissertation boot camp?

-

What did you accomplish during the camp?

-

What tools and techniques of the boot camp did you find most beneficial? Least helpful?

-

-

Graduate Program Experience

-

In what ways do you feel your advisor prepared you for the dissertation process research-wise? Writing-wise?

-

In what ways do you feel your seminars prepared you for the dissertation process research-wise? Writing-wise?

-

To your mind, why is it necessary or not to write a dissertation? What function does it hold for you and your discipline? Asked another way, why do you think we have to do it?

-

Notes

-

The research for this project was in part supported by the 2018 Charles Bazerman Faculty Fellowship for Professional Development in Writing. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

2018-2019 Campus Profile. Campus Profiles. Office of Budget and Planning: University of California at Santa Barbara, January 2019, https://bap.ucsb.edu/institutional.research/campus.profiles/campus.profiles.2018.19.pdf.

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth Wardle, editors. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State University Press, 2015.

Allen, Jan. Graduate School-Facilitated Peer Mentoring for Degree Completion: Dissertation-Writing Boot Camps. The Mentoring Continuum: from Graduate School Through Tenure, edited by Glenn Wright, Graduate School Press of Syracuse University, 2015, pp. 23-48.

Austin, Anne. Preparing the Next Generation of Faculty: Graduate School as Socialization to the Academic Career. Journal of Higher Education, vol. 73, no. 1, 2002, pp. 94-122.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction, Utah State University Press, 2007.

Brooke, Collin and Allison Carr. Failure Can Be an Important Part of Writing Development. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 62-64.

Brooks-Gillies, Marilee, et al. Graduate Writing Across the Disciplines, Introduction. Graduate Writing Across the Disciplines, special issue of Across the Disciplines, vol. 12, no. 3, 2015, pp. 1-8.

Busl, Gretchen, et al. Camping in the Disciplines: Assessing the Effect of Writing Camps on Graduate Student Writers. Across the Disciplines, vol. 12, no. 3, 2015, http://wac.colostate.edu/atd/graduate_wac/busletal2015.cfm. Accessed 30 October 2018.

Caplan, Nigel A. and Michelle Cox. The State of Graduate Communication Support: Results of an International Survey. Supporting Graduate Student Writers: Research, Curriculum, and Program Design, edited by Steve Simpson, et al., University of Michigan Press, 2016, pp. 22-51.

Casanave, Christine. Performing Expertise in Doctoral Dissertations: Thoughts on a Fundamental Dilemma Facing Doctoral Students and their Supervisors. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 43, 2019, pp. 57-62.

Chapman, David. WAC and the First-Year Writing Course: Selling Ourselves Short. Language and Learning Across the Disciplines, vol. 2, no. 3, 1998, pp. 54-60.

Cleary, Michelle Navarre. Flowing and Freestyling: Learning from Adult Students about Process Knowledge Transfer. College Composition and Communication, vol. 64, no. 4, June 2013, pp. 661-687.

Deegan, Mary Jo, and Michael R. Hill. Doctoral Dissertations as Liminal Journeys of the Self: Betwixt and Between in Graduate Sociology Programs. Graduate Education, a special issue of Teaching Sociology, vol. 19, no. 3, 1991, pp. 322-332.

Dissertation Boot Camp Resources. University of North Carolina Writing Center. https://writingcenter.unc.edu/dissertation-boot-camp-resources/.

Gardner, Susan, et al. Socialization to Interdisciplinarity: Faculty and Student Perspectives. Higher Education, vol. 67, no. 3, 2014, pp. 255-271.

Havert, Mandy L. Building Boot Camp Success. Successful Campus Outreach for Academic Libraries, edited by Peggy Keeran and Carrie Forbes, Rowman and Littlefield, 2018, pp. 49-66.

Johnson, E. Marcia. (2014). Doctorates in the dark: Threshold concepts and the Improvement of Doctoral Supervision. Waikato Journal of Education, vol. 19, no. 2, 2014, pp. 69-81.

Keefer, Jeffrey. Experiencing Doctoral Liminality as a Conceptual Threshold and How Supervisors Can Use It. Doctoral Education, special issue of Innovations in Education and Teaching International, vol. 52, no. 1, 2015, pp. 17-28.

Kiley, Margaret, and Gina Wisker. Threshold Concepts in Research Education and Evidence of Threshold Crossing. Higher Education Research and Development, vol. 28, no. 4, 2009, pp. 431-441.

Land, Ray, Jan H.F. Meyer, and Caroline Baillie. Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning. Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning, edited by Jan H.F. Meyer, Ray Land, and Caroline Baillie, Sense Publishers, 2010, pp. ix-xlii.

Lee, Sohui, and Chris Golde. Completing the Dissertation and Beyond: Writing Centers and Dissertation Boot Camps. Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 37, no. 7-8, 2013, pp. 1-6.

Liebermann, Charlotte. Why You Procrastinate (It Has Nothing to Do with Self-Control). New York Times, 25 Mar. 2019, https://nyti.ms/2HWzAg2.

Mastroieni, Anita, and DeAnna Cheung. The Few, the Proud, the Finished: Dissertation Boot Camp as a Model for Doctoral Students. NASPA: Excellence in Practice, 2011, pp. 4-6.

McAlpine, Lynn, et al. "Doctoral Student Experience in Education: Activities and Difficulties Influencing Identity Development." International Journal for Researcher Development, vol. 1, no. 1, 2009, pp.97-109.

Meyer, Jan H.F., and Ray Land. Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge (2): Epistemological Considerations and a Conceptual Framework for Teaching and Learning. Higher Education, vol. 49, no. 3, 2005, pp. 373-388.

Michaud, Michael J. The ‘Reverse Commute’: Adult Students and the Transition from Professional to Academic Literacy. Teaching English in the Two Year College, vol. 38, no. 3, 2011, pp. 244-57.

Papen, Uta, and Virginie Thériault. Writing Retreats as a Milestone in the Development of PhD Students’ Sense of Self as Academic Writers. Studies in Continuing Education, vol. 40, no. 2, 2018, pp. 166-180.

Paré, Anthony. Speaking of Writing: Supervisory Feedback and the Dissertation. Doctoral Education: Research-Based Strategies for Doctoral Students, Supervisors and Administrators, edited by Lynn McAlpine and Cheryl Amundsen, Springer, 2011, pp. 59-74.

Paré, Anthony, et al. The Dissertation as Multi-Genre: Many Readers, Many Readings. Genre in a Changing World, edited by Charles Bazerman, et al, WAC Clearinghouse, 2009, pp. 179-194.

Powers, Elizabeth. Dissercamp: Dissertation Boot Camp ‘Lite’. Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 38, no. 5-6, 2014, pp. 14-15.

Roozen, Kevin. Tracing Trajectories of Practice: Repurposing in One Student’s Developing Disciplinary Writing Processes. Written Communication, vol. 27, no. 3, 2010, pp. 318-54.

Rose, Shirley. All Writers Have More to Learn. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 59-61.

Simpson, Steve. Building for Sustainability: Dissertation Boot Camp as a Nexus of Graduate Writing Support. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, vol. 10, no. 2, 2013, http://www.praxisuwc.com/simpson-102. Accessed 18 October 2018.

---. The Problem of Graduate-Level Writing Support: Building a Cross-Campus Graduate Writing Initiative. Journal of the Council of Writing Program Administrators, vol. 36, no. 1, Fall/Winter 2012, pp. 95-118.

Smith, Ashly Bender, et al. ’Find Something You Know You Can Believe In’: The Effect of Dissertation Retreats on Graduate Students’ Identities as Writers. Re/Writing the Center: Approaches to Supporting Graduate Students in the Writing Center, edited by Susan Lawrence and Terry Myers Zawacki, Utah State University Press, 2018, 204-222.

Sommers, Nancy, and Laura Saltz. The Novice as Expert: Writing the Freshman Year. College Composition and Communication, vol. 56, no. 1, 2004, pp. 124-49.

Starke-Meyerring, Doreen. The Paradox of Writing in Doctoral Education: Student Experiences. Doctoral Education: Research-Based Strategies for Doctoral Students, Supervisors and Administrators, edited by Lynn McAlpine and Cheryl Amundsen, Springer, 2011, pp. 75-95.

Sundstrom, Christine Jensen. The Graduate Writing Program at the University of Kansas: An Inter-Disciplinary, Rhetorical Genre-Based Approach to Developing Professional Identities Composition Forum, vol. 29, Spring 2014, https://www.compositionforum.com/issue/29/kansas.php. Accessed 15 March 2019.

Walker, John H. Drop and Give Me 20 ... Pages. The Pennsylvania Gazette, Sept/Oct 2005, https://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0905/0905gaz07.html. Accessed 30 October 2018.

Weidman, John C., et al. Socialization of Graduate and Professional Students in Higher Education: A Perilous Passage? vol. 28, no. 3. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, Jossey-Bass, 2001.

Winstone, Naomi, and Darren Moore. Sometimes Fish, Sometimes Fowl? Liminality, Identity Work and Identity Malleability in Graduate Teaching Assistants. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, vol. 54, no. 5, 2017, pp. 494-502.

Wisker, Gina, and Maggi Savin-Baden. Priceless Conceptual Thresholds: Beyond the ‘Stuck Place’ in Writing. London Review of Education, vol. 7, no. 3, November 2009, pp. 235-47.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. Learning to Write Effectively Requires Different Kinds of Practice, Time, and Effort. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 64-65.

Dissertation Boot Camps from Composition Forum 45 (Fall 2020)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/boot-camps.php

© Copyright 2020 Kathryn Baillargeon.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 45 table of contents.