Composition Forum 45, Fall 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/

Axiology and Transfer in Writing about Writing: Does It Matter Which Way We WAW?

Abstract: Writing about writing (WAW) is an increasingly popular approach to teaching writing that, while often discussed as a single pedagogy, has always referenced a wide variety of curricula, pedagogies, courses, and assignments. While this diversity has been acknowledged, scholars have yet to fully explore the sources, nature, and implications of this variation. From our reading of over 40 published accounts of WAW courses, curricula, or programs, we articulate a WAW typology using an axiological heuristic that non-reductively but clearly identifies variations of WAW as well as the values that underlie the differences among them. We then explore the implications of these theoretical and axiological differences for the probable results of different WAW approaches, particularly related to claims that WAW effectively facilitates transfer of learning. We conclude with an exploration of questions regarding WAW and transfer that our typology and analysis raise that might be the focus of future research.

A necessary preliminary to orderly speaking and writing is a knowledge of what constitutes order. But this knowledge should be as compact and categorical as feasible; otherwise the time that should be given to practice and to habit-making will be consumed in studying page after page of talk about talking, and writing about writing.

~Preface, Essays in Exposition, 1914

The editors of Essays in Exposition would likely be appalled to know that writing teachers across North America, and beyond (Rudd), are increasingly centering their writing classes around “studying page after page of ... writing about writing,” and then having students write about it. Writing about Writing (WAW), however, continues to emerge as a viable and popular approach to teaching writing. The central defining principle of WAW is to make “writing itself the object of study in the writing classroom” both as the topic of course readings and of student writing (Bird et al., Introduction, 3). This is most often accomplished by presenting writing knowledge through scholarly articles, which both improves students’ ability to read difficult texts and allows them to engage with and write about writing knowledge in conversation with the scholarship that produces, maintains, and disseminates it (Bird Writing; S. Carter; C. Charlton; Downs and Wardle Teaching). WAW is a major reconceptualization of the purpose of first year writing courses. As Rebecca Nowacek notes, writing experts agree instructors “cannot, in one or two semesters, prepare students for all the genres and situation-specific demands that they will face” (201). Writing studies scholarship has shown that writing is so socially situated and content and context bound that no writer masters it but must continually learn to write within new contexts, so WAW “regards helping students think and learn about writing as the appropriate goal of the course (Wardle and Downs, Looking 276, original emphasis). By studying writing, students more deeply engage with key concepts, practice writing, and learn how to learn to write. This convergence of practice and content continues to attract writing instructors.

Another part of WAW’s attractiveness is its inclusivity. WAW has never been a single monolithic curriculum; its proponents regularly disavow any desire to articulate a WAW canon that should be taught or a single set of classroom activities or assignments (Bird; Bird et al. Next Steps; S. Carter; Downs and Wardle Reimagining). Instead, they have pointed toward the many diverse ways instructors have implemented WAW’s principles, allowing for further diversity as new instructors and WPAs develop new approaches for their local contexts. This “wide inclusivity” (Bird et al., Next Steps 271), while admirable, ignores the fact that, as Carol Hayes, et al. note, “not all WAW curricula produce the same effects” (76). In an effort not to imply a single correct way to implement WAW, proponents have avoided clearly articulating differences among WAW approaches and their effects in ways that might help instructors and WPAs select readings, assignments, and class activities.

Doug Downs and Elizabeth Wardle do note several ways approaches tend to differ and even describe a preliminary—though, we will argue, problematic—taxonomy but then shy away from attending to the implications of the differences they identify. The result is that the only attempt to make sense of the wide variety of WAW approaches to date seems to treat differences as inconsequential. We can only conclude that Downs and Wardle’s desire not to seem to promote any one WAW variation, a desire they have adamantly and repeatedly expressed (Teaching, Reimagining; Wardle and Downs Looking, Reflecting), hinders their attempt to usefully describe the WAW landscape. More recently, Barbara Bird, Doug Downs, I. Moriah McCraken, and Jan Rieman assert that “so much diversity exists ... that [WAW] might be impossible to taxonomize” (Writing 18). Such a claim makes sense only if we understand attempts to “taxonomize” as positivistic quests to identify “True” categories. In contrast to this, we argue that WAW approaches cluster in identifiable ways indicative of significant and impactful axiological tensions that both enable and limit what different courses can achieve.

This reluctance to usefully differentiate WAW approaches and to be explicit about different probable and even desired results risks what Richard Fulkerson termed “value-mode confusion” where students, or courses and curricula, are assessed on outcomes the WAW approaches they employ are unlikely to produce (Four Philosophies 347).

Differences among WAW types also have important implications for each approach’s ability to facilitate writing transfer (Anson and Moore; Beach; Perkins and Salomon Knowledge, Transfer; Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström Conceptualizing), which Bird et al. argue is an “outcome and purpose that all [WAW proponents] embrace at some level” (Next Steps 271). While it may be true that WAW scholars have a unanimous devotion to teaching for transfer, different WAW approaches do not, and cannot, teach for transfer in the same ways, nor do they attempt to help students transfer the same knowledge, which raises important questions for the future research we hope our effort here will help make possible.

Finally, greater attention needs to be given to differences among WAW approaches because, as Shannon Carter argues, “informed and research-based disagreement matters and sharpens our various approaches to the teaching of writing in significant and fundamental ways” (S. Carter). Such sharpening is only possible when we not only are inclusive of difference but also attentive to it and its effects.

We, thus, attempt to provide a basis for more such useful disagreements here. We will first identify an axiological heuristic for making sense of the wide variation among WAW approaches and then proceed to identify four emergent types of WAW from published scholarship: process, language/literacy, academic discourse, and context analysis. We will also discuss the different results each type seems designed to produce. Finally, we will briefly draw on transfer research in order to raise important questions about WAW approaches’ abilities to effectively facilitate transfer of writing knowledge. This discussion should show how both current and future WAW scholars can use this axiological heuristic to inform decisions about and assessments of the WAW curricula they design.

A Complex Axiological Heuristic

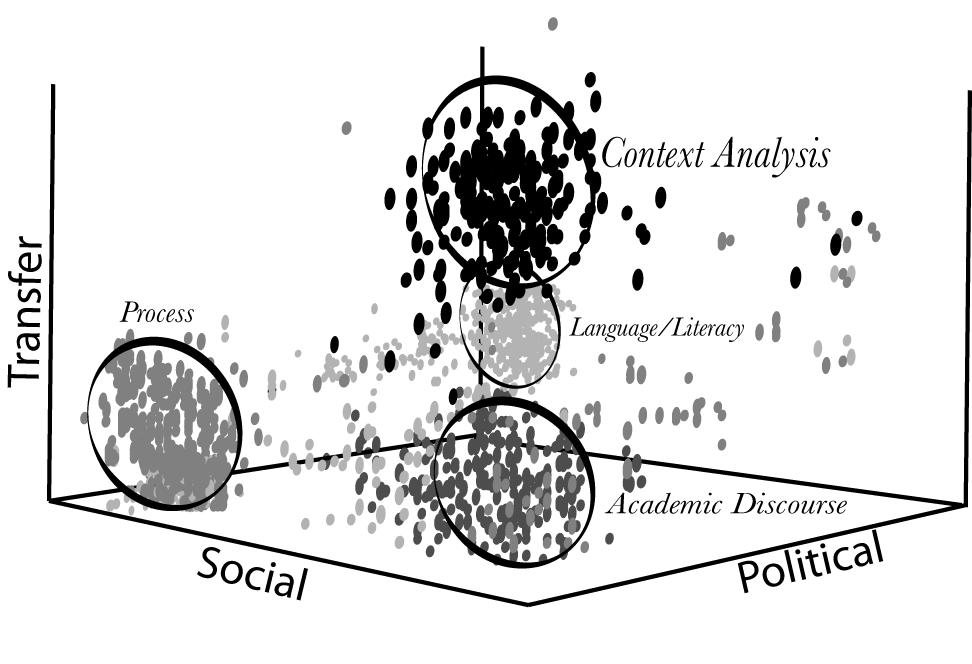

In order to explicate the axiological heuristic we employ, we first acknowledge and take up Downs and Wardle’s taxonomy and why we find it incomplete. In contrast, an axiological heuristic can both explain variation and attend to important differences in WAW approaches while still conforming to Downs and Wardle’s injunction to avoid reductively “misstating what goes on in courses” (Reimagining 139). The heuristic does this by plotting approaches along value axes to reveal patterns and usefully identify dominant types, not as reductive categories, but rather as evident groupings, like groups of points on a scatter graph where approaches cluster to suggest types and distinctive differences (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Four-Axis Scatter Graph

Downs and Wardle identify four “variations” among WAW approaches: the writing subjects prioritized in readings and assignments, the learning goals emphasized, the “types and number of readings, and types and number of writing assignments” (Reimagining 139). They then identify the first criterion, that “WAW curricula ... may focus on writing and literacy from distinctly different angles” in the subjects or topics of readings, class activities, and assignments, as “the most obvious distinction” (139). Finally, based on this criterion and despite the caveat that the “remarkable blends of subject matter [make] it difficult to generalize,” they proceed to “distinguish three categories of approaches”: one that focuses on “literacy and discourse,” another that “focuses on writing studies itself,” and a third that “focuses on the nature of writing and writers’ practices” (139). Downs and Wardle then describe an example of each of these WAW approaches.

We find this taxonomy problematic because while the first and third category do seem to be divided by differences in writing knowledge, the second category seems to be primarily distinguished by a different criterion: presenting writing studies as a discipline. Downs and Wardle seem to recognize this since the heading they use for this category, is “Language/Rhetoric” (Reimagining 141). Even if the heading expresses the real topical distinction, however, this distinction between the first, “literacy and discourse,” category and the second, “language and rhetoric,” becomes indistinct. Discourse by any definition is also language, and, as Downs and Wardle note, Shannon Carter’s Literacy/Discourse curriculum also has “stated objectives” that include “awareness of the influence of context and audience on writing” and “rhetorical flexibility” (Reimagining 141). Similarly, Deborah Dew’s curriculum, the example of the second category, also includes “literacy autobiographies” (Downs and Wardle, “Reimagining” 142). We find far more similarities between Carter and Dew’s courses than differences. The exception is Dew’s identified emphasis on highlighting Rhetoric and Writing Studies as a discipline. But this alters the defining criterion of the category, and, given that all WAW courses introduce students to writing studies research, also seems to be a matter only of degree that we do not find useful. This distinction also creates a problem with Downs and Wardle’s third category since Laurie McMillan’s curriculum also “stresses the content of the course as the content of a scholarly field” (Downs and Wardle, Reimagining 143). These categories, then, do not present sufficiently useful ways to clearly make sense of the variety of WAW approaches.

For our attempt to make sense of WAW approaches, then, we employ a heuristic that accounts for this complexity. We see assignments, courses, and curricula grouped not just according to the writing knowledge emphasized—though this remains the primary point of distinction—but also according to the axiologies that underlie instructors’ curricular and pedagogical decisions.

Richard Fulkerson introduced axiology to composition as “a technical term in philosophy,” which refers to “value theory conceived generally, as opposed to the more specific terms ethics or aesthetics” (Composition Theory 411). Axiology, then, refers to the system of values that lead instructors to choose one set of readings and one set of assignments over another. Fulkerson, however, like other taxonomists (see Berlin, Contemporary, Rhetoric and Reality, Rhetoric and Ideology; Faigley) attempts to relegate scholars to rigidly defined categories that reduce axiology to a single defining value. We reject the idea that instructor choices can be reduced this way. Instead, for the axiological heuristic we employ here, axiologies are most usefully understood as sets of multiple axes or continua between values that come into opposition as instructors are forced by limited time and the needs of local student populations to prioritize one value over another as they choose readings, assignments, and activities. Some instructors seek to find balance among competing values, but most choose to emphasize one value over another. The utility of this heuristic, though, is that it does not limit axiology to single values but can account for instructor’s attempts to negotiate tensions among multiple values. We find that all instructors hold commitments to both ends of these value axes even though they usually choose to emphasize one value over others. Thus even the seemingly most singularly committed scholar makes some attempt, however small, to also accommodate other values. Plotting approaches to composition along axes, then, requires a complex weighing of the relative emphasis an approach places on each value in tension

We derived the axes we use here both from our analysis of published WAW course descriptions and from composition taxonomies (Berlin, Contemporary, Rhetoric and Reality, Rhetoric and Ideology; Faigley; Fulkerson Composition at the Turn, Composition Theory, Philosophies; Winterowd). We find that these oft anthologized taxonomies while they offer somewhat different and shifting categories, derive those categories from four axiological axes of competing values that have substantially contributed to pedagogical variation in composition studies: social, content, political, and transfer. Our axiological heuristic, however, does not limit the number of possible axes, or tensions among competing values, to these four, intentionally allowing for analysis on any number of further axes such as a multimodal or digital axis, but these four axes seem to produce the most significant and contentious divisions in the field. The heuristic also does not require any particular number of axes. We find that three—social, political, and transfer—usefully produce a typology of WAW approaches (see Figure 2), which all share close positions on the content axis and do not seem to significantly vary in relation to other possible axes. The flexibility of the heuristic allows for future shifts that may introduce new tensions between conflicting values, axes, or new consensus that renders any of these irrelevant, but in the snapshot of WAW presented here, these three axes produce a typology that identifies and explains the current diverse array of WAW approaches that, while related to one another, serve varying pedagogical purposes and ideological commitments.

Figure 2. Theoretical Scatter graph of WAW approaches

We develop this typology from the analysis of over forty published accounts of WAW approaches—the majority recently published in the Bird, et al. edited Next Steps. For this initial development of our WAW typology, our analysis remains preliminary and has not been more rigorously codified let alone quantified, steps we intend to take up in subsequent more empirical analyses. The scatter graph is intended only as a theoretical visualization of the four clusters or types of WAW we identify below and how we postulate their relative positions on such a graph and thus does not, yet, correlate to actual data.

We should note that our groupings are influenced by threshold concept theory (Wardle and Adler-Kassner), which, suggests that such concepts “are learned through experiences across time, and are not necessarily learned once and for all” (30). Because threshold concepts are “troublesome” (Perkins), students must encounter them repeatedly and deeply, struggling through pre-liminal, liminal, and post-liminal states before they fully grasp them. This means that any course that hopes to teach threshold concepts, as all WAW courses do, must provide repeated experiences with such concepts to have any hope for students to usefully grapple with them. We can thus conclude that those recurrently and deeply emphasized concepts are the dominant concepts of the course. We group courses by these concepts, then, with some confidence despite attention they give other concepts. Some courses seem to give more equal attention to multiple concepts (di Genarro; Johnson; Tremain), making them more difficult to place, though we still make tentative holistic judgments regarding the concepts students seem to encounter most, or reference the same author in relation to two types (Johnson). Future research is needed to determine if a course can effectively balance approaches in a way that allows students to sufficiently encounter all threshold concepts or if an attempt to balance prevents students from grappling sufficiently with any of them. Because an axiological heuristic does not require definitive placement in categories, however, the complexity of the ways approaches balance values does not prevent the application of the heuristic to identify emergent types.

Axiological Groupings: Plotting WAW Approaches

Kristen di Gennaro articulates the social axiological tension when she complains about “faculty who misunderstood WAW as an extension of the expressivist model of composition, where students write primarily about their own experiences with writing” arguing instead that in WAW, as she sees it, “writing tasks might draw on students’ observations and reflections” but it “is not writing about my writing” (120, original emphasis). Readers will likely recognize the familiar tension between writing as individual expression and writing as social interaction, or, in Patricia Bizzell’s terms, between inner-directed and outer-directed approaches: individuals and contexts.

While di Gennaro reifies the “expressivist” category of the past, however, we find that WAW approaches take positions all along the social axis. Individual and group, inner-directed and outer-directed, might constitute extreme positions on this axis, but curricula rarely, if ever, take such extreme positions. Christina Grant, whose description of her WAW first-year writing (FYW) course for international students centers on how it helps “multilingual students reclaim their voices” with a predominance of process articles and popular essays from public figures and creative writers—exactly the sort of WAW curriculum di Gennaro criticizes—also asks students to “study Anne Beaufort’s (2007) five knowledge domains” which include social concepts like discourse communities and genre (77). This lesser but notable attention to the social aspects of writing might not be enough to balance the otherwise dominant emphasis on writing processes and voice, but it shows that Grant’s curriculum cannot be reduced to a single expressive value. Instead, Grant, while moved primarily by concern for her students’ individual voices, also attends at least somewhat to rhetoric and social context as well. Where past taxonomies would ignore this duality to reductively highlight Grant’s prioritization of voice, our axiological heuristic allows for a more complex analysis that presupposes the interplay of values that underlie curricular and pedagogical choices.

Other WAW approaches seem to fall closer to the midpoint between attention to students’ own processes, experiences, and identities and the expectations and conventions of social context. Downs and Wardle note that the curriculum of the University of Central Florida attempts to balance values by employing different units—thus including readings and assignments from multiple WAW approaches (Reimagining 140). Frances Johnson begins her course with “an auto-ethnography in which students examine their writing process” before they “record the writing process of other students” and finally examine “the artifacts produced by the scientific discourse community,” thus moving from self- to context-analysis(174). This contrasts not only with courses like Grant’s but also with courses like Andrew Ogilvie’s that situates the entire course in “a central debate in our field involving whether a single academic discourse exists, and whether writing instructors should or could teach a set of ‘general’ writing skills” (144-45). Students conduct a corpus analysis of journal articles in their majors, attending to both similarities and differences in order to come to an informed position on the question. In such a course, context analysis becomes primary; although, Ogilvie also relates that they begin the course by discussing student’s own “perceptions of writing” thus still attending, at least somewhat, to students’ individual experiences and reflections on their own writing (144).

By plotting WAW approaches along this axis, we can, as we state above, avoid reductively misrepresenting WAW approaches, but we can also still attend to and identify significant and distinctive differences, including, we will show, further axiological tensions that help account for and make sense of variation.

Among WAW approaches that tend toward the inner-directed or individual we find two types: those that focus primarily on writing processes (Aksakalova and Zino; Bird Writing; DeJoy; C. Charlton; J. Charlton; Grant; Hart; Hoover et al.; Johnson; McCracken and Ortiz; Ruecker; Slomp and Sargent; Smith, Frick, and Siebel; Tremain; Wenger) and those that emphasize students’ relationships to language and/or literacy (S. Carter; Casey; Dew; Looker; Sanchez, Lane, and Carter; Tremain; Wilson, Jackson, and Vera). While these groups can be identified both topically and by the language and literacy type’s greater emphasis on culture and society, we also find that they are separated by another axiological tension: the political axis. Those who choose to emphasize language and literacy seem to be more motivated by intentional classroom activism related to literacy (S. Carter) and language diversity (Looker). This is not to say that those who emphasize process attempt to be apolitical; many would likely argue, as Christina Grant does, that they are activists in “reestablishing and empowering ... students’ voices” (83). Where such attention to the activism is a secondary concern outweighed by a focus on students’ writing processes in courses like Grant’s, however, in language and literacy courses, activism seems to be a much more central focus.

Among those tending more toward the outer-directed or group value, we also find two main groupings: those that focus more on a general academic discourse and academic writer identities (Bird A Basic; di Gennaro; Kleinfeld; Johnson) and those that focus on context analysis (Arbor; Cutrufello; Hardy, Romer, and Roberson; LaRiviere; Lucchesi; Mahaffey and Rieman; Ogilvie; Read and Michaud Negotiating, Writing; Robinson; Stinson; Wells; Wenger). These types are divided by their positions on the transfer axis: the axiological tension between teaching general writing knowledge (M. Carter; Foertsch; Thonney) and the realization that writing is so thoroughly situated that it must always be learned locally in specific contexts (Russell; Smit). These types, then, are divided by whether they attempt to teach a general academic discourse that exists despite disciplinary variation or whether they seem to agree that “such a unified academic discourse does not exist” and instead attempt to provide context analysis tools to help students more efficiently learn to write in future contexts (Downs and Wardle, Teaching 552).

We will seek to articulate the common features of each of these groupings, moving from those we see as focusing most on individuals to those most focused on contexts. For each group, we will take up the question of what results each type might expect to achieve.

An Axiological WAW Typology

Process WAW

Contrary to di Genarro’s assertion, WAW approaches that focus on students and their own writing processes seem to be among the longest established (Bird et al. Writing; DeJoy; Slomp and Sargent), and a variety of process WAW approaches have emerged, from Grant’s focus on voice for multilingual writers to the composition program at The University of Texas-Pan American (C. Charlton; J. Charlton; McCracken and Ortiz). In such courses students “become active, participatory learners and experts on their own writing processes who feel they have important contributions to make to ongoing conversations about writing and much else” (Grant 84, emphasis added). These courses do this through assignments that ask students, through various means, to attend to their current writing processes while they read a wide variety of process scholarship in order to “evaluate their past reading and writing patterns to identify literacy practices that should be adapted, adopted, or alienated” (McCracken and Ortiz). Like all individual focused WAW approaches, process WAW assignments, courses, and curricula focus on helping students relate their own prior experiences, in this case their writing processes, to scholarship through extensive reflection and developing meta-cognitive awareness of available strategies for reading, writing and research.

We must reiterate, however, that no process course reads only process research or asks students only to research their own or even others’ processes. As far as we can tell, all WAW courses include readings on rhetoric and in many cases discourse communities (see Johnson), but, by our reading, a majority of readings, assignments, and we assume time, remains on the overall focus of students’ processes. McCracken and Ortiz describe a first-year course sequence in which “the first course in the sequence [helps] students learn something new about their processes and practices as a way to find their own entry points in unfamiliar readings” and then in “the second semester ... [students] extend their understanding of (academic) writing and research conversations by developing large-scale investigations into writing-related issues. In this second course, process seems to remain prominent as McCracken and Ortiz note that student projects “are often extensions of the first-semester course conversations.”

We also include some other described courses that do not identify as process approaches (Ruecker; Johnson), but we find that they, at least to some extent, do emphasize process over other concepts. Todd Ruecker’s described course is a prime example since though he argues that he intends to focus the course on epistemic rhetoric, nine of twelve assigned articles are on process (101-102), and quoted student reflections seem to support the conclusion that the threshold concepts students grapple with most relate to process (94-95).

The impact such courses seem to have on students, then, is a deep, reflective, and metacognitive awareness of writing, and often research, processes, both their own and others’, often through empirical research projects. We might expect that such courses would be assessed on students’ knowledge about processes as well as their ability to employ effective, and reflective, process strategies. We would not expect students who complete such courses to be able to give sophisticated explanations of concepts like genre or activity systems, or to be able to analyze the differences among genres or disciplinary conventions. We would also not expect students to offer deep insight into language diversity or literacy sponsorship (Brandt). A course like Grant’s will also likely have different impacts on students than one like Ruecker’s, but all these courses, we think, will “[shift] students’ perception of writing studies and their very identification as writers” (Hoover et al. 210).

This effect on students’ perceptions of themselves as writers seems to be a primary concern for all instructors who choose to focus on students as individuals, or, in terms from transfer theory, on student dispositions (Driscoll and Wells: Wardle “Creative”), particularly the disposition of self-efficacy (Driscoll et al.; Grant; Tremain). Dispositions have, however, proven to be particularly complex and difficult to research (see Driscoll et al.). We will raise important questions about dispositions in transfer below.

Language and Literacy WAW and the Political Axis

While they share a focus on individual student identity and self-efficacy with process approaches, language and literacy approaches to WAW, as we note above, both give greater attention to the social nature of writing and, in doing so, are more activist, not only more so than process approaches but also than other WAW approaches. As with any of these value axes, some approaches, such as Looker’s, are further along the political axis than others, such as Tremain’s, just as some are further along the social axis than most others, but we find the nature of the language and literacy scholarship that such approaches ask students to read and write about makes such courses unavoidably more attentive, at least somewhat, to issues of diversity and social justice than others. Samantha Looker argues that the greatest benefit of her writing-about-language course is “an ongoing commitment to minimizing linguistic segregation and prejudice, to creating an understanding of academic discourse that does not exclude students or scholars from nonstandardized language backgrounds” (178). Looker’s interest in such classroom activism connects with how Shawn Casey notes that his “students often quickly connect” the assigned readings “in response to problems or challenges posed by the social inequalities addressed in critical literacy pedagogies” and “begin to reflect on and talk about the contexts of their own literacy learning” (141). This work to promote greater understanding of the inequities integral to language and literacy are central to this type of WAW approach.

Within this group, some focus primarily on language (Looker; Wilson, Jackson, and Vera) and others focus more on literacy (S. Carter; Casey; Mutnick; Sanchez, Lane, and Carter; Tremain), but we keep them together, for now, because of a shared attention to helping students make sense of their prior literacy experiences. As with process WAW, the most common assignment is some form of self-study but one that asks students to describe their own experiences and to analyze them through the lens of language diversity and/or literacy—particularly Deborah Brandt’s concept of literacy sponsorship. Courses do then build from such assignments, gradually directing students’ attention outward in interesting ways.

While language and literacy scholarship, and thus any course built around it, certainly attends to the social nature of language and literacy, the focus usually remains on students’ experiences rather than asking students to, say, make theoretical arguments about teaching standard English, or the systemic discrimination of systems of literacy sponsorship—though final projects might allow students to make such arguments if they choose. Many language and literacy approaches do include readings and some final assignment that connect the course to academic discourse and even concepts like discourse communities (see Looker; Sanchez, Lane and Carter). Sánchez, Lane, and Carter do this by beginning with a literacy self-study, then a multimodal online literacy narrative using Tumblr, and culminating with an ethnographic essay and website that presents information they gather through both primary and secondary research on how a particular “chosen discourse community functions” (125). This final project, though, seems to be much more of an identification of a group, usually from among “on-campus clubs and organizations,” as a community, with descriptions of the group’s “common goals and practices” rather than attention to differences in writing conventions (125). So, despite the substantial number of readings on discourse communities, the clear focus on students’ literacy experiences remains dominant, though in many if not most cases, a secondary focus on academic discourse emerges. This attention to a general academic writing serves to connect the political goals to more pragmatic developmental purposes.

Such courses, then, might be assessed according to their ability to help students employ common features of academic writing. Because this is a secondary goal of such courses, an assessment of how well they develop students’ understanding of social issues of language and literacy might be more appropriate. Research on such courses might focus on testing how well they do indeed teach students to employ conventions of “academic writing” in addition to teaching important knowledge about language and literacy and engaging in productive classroom activism.

As we note above, language and literacy WAW approaches, like process WAW, seem to aim to productively develop students’ generative dispositions, particularly self-efficacy (Tremain), though few scholars have specifically used those terms. Most, like Looker, frequently argue that such courses “help students feel more capable as academic writers” (190). Given the intense attention to students’ own experiences with literacy and language, it is easy to see how students may develop self-efficacy as they increasingly come to see themselves in the scholarship they read and as valid participants in the production of such scholarship. Future research is needed to measure just how well such courses do foster generative dispositions and whether this productively fosters transfer.

Academic Discourse WAW: Academic Writer Identity and Academic Discourse

Like many of the language and literacy approaches, and many process approaches as well, the type of WAW approach that we are calling Academic Discourse focuses on teaching students “academic writing conventions” (di Gennaro 116), but what seems secondary in other approaches becomes primary. Despite varying levels of attention to differences among disciplines, such approaches maintain a focus on common features like source use (Kleinfeld) or employment of the moves described in John Swales “CARS Model” (Johnson). While some of these approaches also focus on identity, it is the development of an “academic writer identity” (Bird, A Basic 65). This is evident in the difference between an identity-focused literacy approach, like Tremain’s, and Barbara Bird’s academic discourse approach. Although both authors heavily stress helping students develop writerly identities, where Tremain’s discussion of her approach remain in general terms of “literacy development” and self-efficacy, Bird argues, “Writing strategies unattached to academic discourse purposes and separated from holistic dispositional involvement cannot sustain quality writing or enable transfer” (Bird, A Basic 69). Tremain’s course is in many ways very similar to Bird’s; her focus on literacy is among those least attentive to activism, and like Bird’s is more focused on identity than others, but Bird ties her course closely to helping students learn the conventions of a general academic discourse.

Courses that engage students in “academic research” projects often fall within this type when the features of the writing studies genres they produce are presented without sufficient discussion of differences from other disciplines, professions, or publics. Such is also the case when courses emphasize broad similarities across academic disciplines more than differences, which can be overshadowed by a reified conception of general academic discourse, especially when a course focuses on surface differences like language and style, with little attention to genre and communities of practice. di Gennaro mentions at multiple points that her course not only “focuses on academic writing conventions” but also “how these vary across discourse communities,” but she also repeatedly discusses “academic writing” in ways that imply a generalized universal discourse, such as noting “one main objective ... to develop students’ awareness of ... conventions, preferences, and expectations of academic writing’” and the readings and assignments seem to support this emphasis on general features of academic discourse over differences (e.g, Thonney) (116). So, though we can certainly see arguments for why di Gennaro fits into the last of our types—or may fall between the two, we feel many students likely leave such courses with more knowledge of supposed general academic discourse conventions than of the significant ways they differ among disciplines and how such differences can be analyzed.

Academic discourse approaches, then, should be assessed on improvement in students’ knowledge about and implementation of these general features of academic writing: use and integration of sources, argumentation, language features like hedges, etc. For courses like Bird’s, that focus on academic writerly identity, assessment might also look for evidence of students’ developing the academic dispositions she identifies.

Like both previous types, academic discourse approaches also claim to develop generative student dispositions like self-efficacy; however, they further argue, as Bird does, that effective transfer, at least to writing in other academic disciplines, requires explicit knowledge of academic discourse conventions. This implies that general process, language, or literacy—along with varying amounts of rhetorical knowledge—is insufficient for effective transfer unless it is clearly connected to academic discourse conventions, raising the questions of what knowledge transfers— a question that Rebecca Nowacek notes writing studies has neglected—and where it should transfer to. Academic writing is not the only writing students may need or want to do in the future after all.

Context Analysis: The Transfer Axis and Teaching to Transfer

While they diverge on the social and political axes, all three of the types we have plotted thus far closely align on a third axis in our heuristic. They all attempt to teach general writing knowledge, whether general procedural knowledge about writing processes, general knowledge about language or literacy, or general academic discourse conventions, or some combination of these. The implication is that these scholars believe such general knowledge is universally applicable: that students use their knowledge of process or academic conventions to write in new contexts. This valuing of knowledge that seems generally applicable to some extent is one end of the transfer axis in our axiological heuristic. The other end is the valuing of knowledge useful for analyzing local writing since writing is, reportedly, too socially and historically situated for such general knowledge to be useful. This tension between general and local knowledge occupies early transfer scholarship in writing studies (M. Carter; Foertsch).

Context analysis WAW approaches focus on teaching students to analyze communities, activity systems, and/or genres as a means of more efficiently learning to write in local contexts (Arbor; Cutrufello; Hardy, Romer, and Roberson; LaRiviere; Lucchesi; Mahaffey and Rieman; Ogilvie; Read and Michaud Negotiating, Writing; Robinson; Vetter and Nunes; Wells). The focus of such approaches is on teaching students how disciplines, communities, or professions’ discourse expectations and conventions differ and how students can use sophisticated understandings of concepts like genre to learn to write in those local contexts.

As with all the types we’ve defined, such approaches do not occupy a rigid category but a range of points within a moderate—currently metaphorical—standard deviation. Some appear quite similar to academic discourse approaches (Hardy, Römer, and Roberson; Ogilvie). Andrew Ogilvie’s course, just like di Gennaro’s makes use of Teresa Thonney’s argument for identifiable features of academic discourse, but unlike di Gennaro, Ogilvie “asks students to contribute to an ongoing debate within writing studies over the notion of a universal academic discourse, using their disciplinary majors as a case study” (143-44). According to Ogilvie, this exercise to contribute to a disciplinary debate provides “a simulation of the experience of writing oneself into a discourse community—in this case, the discipline of writing studies” (143), which, he argues “makes explicit the kind of approach [to learning to write] they will need in their major” (145).

Jack A. Hardy, Ute Römer, and Audrey Roberson’s corpus based WAW approach also may appear similar to di Gennaro’s given the ways they often attend to stylistic features of academic texts, but even more than Ogilvie, they argue that a key purpose and benefit of their students exploration of disciplinary student papers in the Michigan Corpus of Upper-level Student Papers (MICUSP) is “to equip students with appropriate tools for learning that go beyond a particular writing task or course and to turn them into explorers of the disciplines they wish to be a member of” (emphasis added). They also put more emphasis on differences, noting that “students reported having benefited from the heightened awareness and understanding of disciplinary differences.” This attention to difference keeps the focus clearly on learning “how to analyze and adjust to writing requirements in future courses and even life outside academia.”

As far as we can determine, every context analysis WAW approach includes the empirical study of a discipline, profession, or other group using interviews, genre analysis, corpus analysis, surveys, etc. not just to describe the discipline broadly but to identify its unique genres, expectations, and conventions. This deeply engaging work allows students to “retheorize writing through encountering and exploring the ways in which, and the reasons why, academic writing differs from one field to another, to see that writing both shapes and is shaped by the values and practices of various fields of study” (Robinson 45). Such assignments often draw heavily on rhetorical genre theory as “students learn to analyze genre models, to make generalizations, and to formulate plans for performing in unfamiliar genres” (Lucchesi 152). In such courses “students ... explore acts of reading and writing: the people who do it, how they do it, and how to help others do it” (Wells 58). Rather than just teaching for transfer, the goal in such approaches seems to be to teach students to transfer.

As Sarah Read and Michael Michaud argue, such courses propose “that if students learn how to do genre analysis as a practice of writing research, they will be able to recall the general practices ...of genre analysis in a future ... writing situation” (Writing 444). Students, then, are not just deeply reading about, discussing, and reflecting on theoretical concepts like discourse community, activity theory, and genre; they are learning to use such concepts to transfer by analyzing new contexts to determine how to adapt their writing to those contexts. Students, courses, and curricula, then might most usefully be assessed on both students emerging understanding of key concepts like genre and how well they employ such concepts to analyze writing contexts. This analysis, however, is not confined to differences, since analysis also requires attention to similarities in order for students to draw on their prior knowledge, but such similarities emerge and are tested through analysis using key writing concepts.

In terms of transfer, then, context analysis WAW approaches focus on the transfer of key writing concepts that enable students to analyze new writing contexts, the knowledge and strategies for learning to write in new contexts. As Read and Michaud argue, such courses “attempt to instill in students a flexible and adaptable writerly subjectivity that sees each new writing task as an opportunity for new learning” (Writing 454). Downs and Wardle have also emphasized this focus on what Wardle terms “expansive learning” (Creative; see also Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström Conceptualizing). They argue that “the transferable knowledge is not the answers but the questions: not ‘how to write,’ but how to ask about how to write” (Reimagining 134). Read and Michaud also, though, in seeking “to instill a flexible and adaptable writerly subjectivity,” show that such courses have the same interest as other approaches in developing generative student dispositions (Writing 454). All WAW courses, then, attempt to facilitate transfer through attention to dispositions, but each type seeks to transfer both slightly different dispositions and different knowledge (process, critical literacy/language diversity, academic discourse, contextual analysis concepts and strategies) in different ways. Since facilitating transfer is central to the theory and benefits of WAW, we will turn to some questions that our reading of transfer scholarship raises about these WAW approach’s claims about transfer.

The Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Facilitating Transfer

A full review of transfer scholarship and discussion of its implications for WAW approaches is not possible in the remaining space of this article, but our typology has revealed certain evident differences in how each approach attempts to facilitate transfer that raise certain questions that suggest important directions for subsequent WAW research.

Transfer is a highly criticized metaphor (Beach; Wardle Creative), but despite critiques of the term, as Rebecca Nowacek notes, “the word transfer continues to function as a big-tent term for many acts of connection-making” (202). A simple definition of transfer is the use of knowledge learned in one context in a new target context, but, lacking the space to explore definitions of transfer, we agree with many other scholars that transfer is far more complex than carrying knowledge from a learning context to a target context. Writing transfer, or “creative repurposing” (Wardle Creative para. 8), requires conscious (re)construction of prior experiences that can be adapted for new writing contexts. It is this mindful process that WAW proponents claim to facilitate, but research is needed to determine whether some may be more likely to succeed than others.

The Difficulty of Dispositions

As we have shown, all WAW approaches, to some extent or another, claim to develop students’ generative dispositions. Such claims have not yet been tested. As with much of WAW scholarship, evidence remains largely anecdotal: selective, though promising, quotations from student reflections and other qualitative instruments. There is a real need for more research into WAW and its ability to foster generative student dispositions; such research might take up the following questions:

Is improved self-efficacy sufficient to produce the generative dispositions that facilitate transfer? Does self-efficacy transfer?

It is surprising that WAW scholars who focus on the development of writer identities and self-efficacy do not situate their claims in emerging scholarship on dispositions within writing studies (Driscoll; Driscoll et al.; Driscoll and Wells; Wardle Creative). This research has demonstrated that student dispositions are complex. Building on Driscoll and Wells work, Driscoll et al. set out to study what they identify as five key dispositions: “attribution, self-efficacy, self-regulation, ... value, [and] persistence.” For each of these types, students may have either generative (facilitate transfer) or disruptive (inhibit transfer) dispositions. Additionally, Elizabeth Wardle looks at broader “problem-exploring” or “answer getting” dispositions. Thus, a broader consideration places self-efficacy among a complex of dispositional factors that may affect both the fostering of generative self-efficacy and transfer, including whether improved self-efficacy itself is transferrable (Creative). Driscoll et al. summarize Metcalf Latawiec who “argues persuasively that self-efficacy is task specific, rather than generalizable.” If self-efficacy is as situated as writing, how likely is a student to transfer improved self-efficacy beyond the WAW classroom? Might gains in self-efficacy be seen by students as unrelated to the later writing they do? Transfer research has shown that students often strangely dissociate their experiences in writing classes from writing in other contexts (Bergmann and Zepernick; Driscoll).

Are generative dispositions necessary but insufficient to facilitate transfer

Dispositions, then, have been shown to affect transfer of learning—and initial learning for that matter—and WAW approaches all claim to usefully develop generative student dispositions. Dispositions, however, do not of themselves lead to transfer. Like other elements within the dynamic and complex network of factors that impact learning and transfer, dispositions may be necessary but insufficient to facilitate effective transfer. Approaches that overly focus on developing student dispositions, then, risk not providing sufficient transferable writing knowledge to capitalize on improved dispositions.

Do explorations of language and literacy have a greater impact on student self-efficacy than process, academic discourse, or context analysis?

While all WAW approaches argue that they help students develop generative writing identities and dispositions, language and literacy WAW approaches do so by most directly addressing factors that may have led students to develop low self-efficacy in the first place, especially for traditionally marginalized populations who feel most alienated by the language of academia. Self-efficacy from extensive reflection on processes (Grant), the features of academic writing (Bird), or concepts for context analysis, will not connect to students’ prior experiences as deeply as frank engagements with language and literacy. Does that, however, translate to broader development beyond the essential political project inherent in it? Is that political activism simply reason enough regardless of what “transfers”?

The Questions of What and What Difference It Makes

Beyond dispositions, each type differs in what knowledge it seeks to transfer, which raises the following questions:

Does process need to be directly taught?

How much benefit is there in having students read, discuss, reflect on and write about classic 1970s and 80s process scholarship, or the process writings of popular authors? How useful is engaging students in their own 1980s style empirical process research like write aloud protocols? All contemporary approaches to teaching writing require students to engage in complex writing processes, and all WAW approaches also advocate various means of asking students to reflect on and develop metacognitive awareness as mindful writers. In truth, context analysis is itself a part of a complex social writing process, so we question whether process WAW approaches truly teach transferable conceptions of writing processes better than other WAW approaches. We find that each semester, students who were not asked to read process scholarship or conduct process research nevertheless frequently name process as one of the most important writing principles they learned in end of term reflective essays. The benefits of explicit process approaches to WAW become moot if they cannot be shown either to better teach transferable process knowledge and skills or to better foster generative dispositions.

What writing knowledge does transfer, and what difference does it make?

Rebecca Nowacek notes that writing studies has largely neglected the question of what writing related knowledge transfers, but in looking at the knowledge different WAW approaches ask students to engage with, we might also ask about another neglected concept in writing transfer: amount. Salomon and Perkins define amount in transfer theory not as how much knowledge is transferred but instead as “how much improvement (or, in the case of negative transfer, decrement) results in the transfer context from attaining some level of performance in the learning context” (123). In other words, what impact does deep, reflective, and metacognitive engagement with certain writing research have on student writing in subsequent writing situations versus others? This question is important since, as we note above, the process of learning threshold concepts requires deep and repetitive engagement with those concepts, and students can only transfer knowledge that they have at least partially “learned.” It is also essential because some concepts that might most affect amount, or impact, of transfer might be the most troublesome and require the most time and prolonged engagement. Carol Hayes, Ed Jones, Gwen Gorzelsky, and Dana L. Driscoll in the only study to compare different approaches to WAW to date found that “given the complexity of genre as a concept, an explicit writing studies curriculum might be necessary to teach it effectively” (82). This conclusion came from noting the statistically significant difference in student metacognitive reflections on genre between a genre-focused context-analysis WAW curriculum and a WAW approach described as focusing on the rhetorical situation (Hayes et al. do not provide enough detail to determine whether that focus would entail a process, academic discourse, or context analysis approach, or if it might fall outside our typology). If a sophisticated understanding of genre is an important writing knowledge to transfer, then only context analysis WAW approaches may be adequate to produce such transfer.

Is context analysis necessary to facilitate transfer?

Among the “practices that promote writing transfer” researchers identify in the Elon Statement on Writing Transfer is “constructing writing curricula and classes that focus on study and practice with concepts that enable students to analyze expectations for writing and learning within specific contexts” (Anson and Moore 353). Anson and Moore note that for students to transfer effectively they may need “support” that “comes from what students have learned previously in courses that provide explicit instruction in the processes of transfer” (334, emphasis added). Practice in contextual analysis, then, may be necessary for transfer, and this perspective seems increasingly common among transfer researchers. This may be a reason that every scholar to design a WAW approach for professional writing that we have found has developed a context analysis approach (Arbor; Cutrufello; Lucchesi; Read and Michaud Negotiating, Writing; Vetter and Nunes). Because these courses aim to prepare students for writing in multiple unfamiliar professions, instructors likely feel strongly that students will need to be able to analyze workplace contexts.

Does when and to whom matter as much as what?

What approaches, then, may be most appropriate for particular student populations? Where professional writing WAW courses have employed a context analysis approach, scholars designing basic writing WAW courses, or courses for traditionally underserved populations, in contrast, overwhelmingly choose either process (C. Charlton; J. Charlton; Grant; Hart; McCracken and Ortiz) or language/literacy approaches (S. Carter; Mutnick; Sanchez, Lane, and Carter; Wilson, Jackson, and Vera), with the exception of Barbara Bird’s academic discourse WAW approach. Might such individual focused courses better prepare students to benefit from a later context analysis course? Or, could a context analysis approach be stretched over two semesters while also achieving the same benefits of other approaches?

Conclusion

We could likely come up with many further questions about transfer—like what, and what types, of general knowledge transfers: genre knowledge, after all is also “general” knowledge in a sense, but is significantly different from general knowledge about writing with sources or employing hedges—and other proposed benefits of WAW, but what we have here is sufficient to show how attending to differences among WAW approaches provides important avenues for further research and what may become important points of disagreement. While Writing about Writing has indeed emerged as a viable approach to teaching writing, continued progress and growth will depend on further research, assessment, and refining. Such work will only progress with the clearer picture of differences amongst WAW approaches we have laid out here, and which we hope to refine as we devise methods for coding and quantifying and testing our analysis, a project we hope other researchers might take up as well.

Works Cited

Anson, Chris M. and Jessie L. Moore, editors. Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer. U Press of Colorado, 2017.

---. Introduction. In Anson and Moore, pp. 3-13.

Arbor, Joy. WAW-Professional Writing for Stem Co-Op Students. Bird et al., pp. 71-74.

Askalova, Olga, and Dominique Zino. Processes of Engagement: A Community College Perspective. Bird et al., pp. 146-49.

Beach, King. Consequential Transitions: A Developmental View of Knowledge Propagation through Social Organizations. Terttu Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström, pp. 39-63.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State UP, 2007.

Bergmann, Linda S. and Janet S. Zepernick. Disciplinarity and Transfer: Students’ Perceptions of Learning to Write. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no. 1-2, 2007, pp. 124-149.

Berlin, James A. Contemporary Composition: The Major Pedagogical Theories. College English, vol. 44, no. 8, 1982, pp. 765-777.

---. Rhetoric and Ideology in the Writing Class. College English, vol. 50, no. 5, pp. 477-494.

---. Rhetoric and Reality: Writing Instruction in American Colleges, 1900-1985, Southern Illinois UP, 1987.

Bird, Barbara. A Basic Writing Course Design to Promote Writer Identity: Three Analyses of Student Papers. Journal of Basic Writing, vol. 32, no.1, 2013, pp. 62-96.

---. Writing about Writing as the Heart of a Writing Studies Approach to FYC: Response to Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle. ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions’ and to Libby et al. ‘Thinking Vertically.’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 60, no. 1, 2008, pp. 165-171.

Bird, Barbara, Doug Downs, I. Moriah McCracken, and Jan Rieman. Conclusion: Afterwards and Forwards. Bird et al. pp. 271-79.

---. Introduction. Bird et al., pp. 3-12.

---. Next Steps: New Directions for/in Writing about Writing. Utah State UP, 2019.

---. Writing about Writing: A History. Bir et al., pp. 13-20.

Brandt, Deborah. Sponsors of Literacy. College Composition and Communication, vol. 49, no. 2, 1998, pp. 165-185.

Carter, Michael. The Idea of Expertise: An Exploration of Cognitive and Social Dimensions of Writing. College Composition and Communication, vol. 41, no. 3, 1990, pp. 265-86.

Carter, Shannon. Writing about Writing in Basic Writing: A Teacher/Researcher/Activist Narrative. Basic Writing e-Journal, vol. 8-9, 2009/2010, https://bwe.ccny.cuny.edu/Writing%20About%20Writing%20in%20BW.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2019.

Casey, Shawn. Community College Composition, Critical Literacy, and the Writing about Writing Curriculum. Bird et al., pp. 137-142.

Charlton, Colin. Forgetting Developmental English: Re-Reading College

Reading Curricula. Basic Writing e-Journal, vol. 8-9, 2009/2010. https://bwe.ccny.cuny.edu/Forgetting%20Developmental%20English-%20%20Re-Reading%20College%20Reading%20Curricula.pdf, Accessed Accessed 15 May 2019.

Charlton, Jonikka. Seeing in Believing: Writing Studies with ‘Basic Writing’ Students. Basic Writing e-Journal, vol. 8-9, 2009/2010, https://bwe.ccny.cuny.edu/Seeing%20is%20Believing-%20%20Writing%20Studies%20with%20“Basic%20Writing”%20Students.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Cutrufello, Gabriel. Writing about Writing Pedagogy in a Mixed Major/Nonmajor Professional Writing Course. Bird et al., pp. 155-58.

DeJoy, Nancy C. Process This: Undergraduate Writing in Composition Studies. Utah State UP, 2004.

Dew, Debra Frank. Language Matters: Rhetoric and Writing I as Content Course. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 26, no. 3, 2003, pp. 87-104.

di Gennaro, Kristen. Next Steps, Or Rather, One Step at a Time: A How-To Guide for Implementing Writing about Writing. Bird et al. pp. 112-122.

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. Teaching About Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning FYC as Intro to Writing Studies. College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no.4, 2007, pp. 552-84.

---. Reimagining the Nature of FYC: Trends in Writing-about-Writing Pedagogies. Exploring Composition Studies: Sites, Issues, and Perspectives, edited by Kelly Ritter and Paul Kei Matsuda, Utah State UP, 2012, pp. 123-44.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn. Connected Disconneted, or Uncertain: Student Attitudes about Future Writing Contexts and Perceptions of Transfer from First Year Writing to the Disciplines. Across the Disciplines, vol. 8, no. 2, 2011. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/articles/driscoll2011.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, et al. Down the Rabbit Hole: Challenges and Methodological Recommendations in Researching Writing-Related Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol. 35, 2017. https://compositionforum.com/issue/35/rabbit-hole.php. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol 26, 2012. https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Faigley, Lester. Competing Theories of Process: A Critique and a Proposal. College English, vol. 48, no. 6, 1985, pp. 527–542.

Foertsch, Julie. Where Cognitive Psychology Applies: How Theories about Memory and Transfer Can Influence Composition Pedagogy. Written Communication, vol. 12, no. 3, 1995, pp. 360-83.

Fulkerson, Richard. Composition at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. College Composition and Communication, vol. 56, no. 4, 2005, pp. 654-687.

---. Composition Theory in the Eighties: Axiological Consensus and Paradigmatic Diversity. College Composition and Communication, vol. 41, no. 4, 1990, pp. 409-429.

---. Four Philosophies of Composition. College Composition and Communication, vol. 30, no. 4, 1979, pp. 343-348.

Grant Christina. ‘I Am Seen; I Am My Culture; And I Can Write.’: How WAW Returns Multilingual Learners to Voice, Building Self-Efficacy and Rhetorical Flexibility. Bird et al., pp. 75-87.

Hardy, Jack A., Ute Römer, and Audrey Roberson. The Power of Relevant Models: Using a Corpus of Student Writing to Introduce Disciplinary Practices in a First Year Composition Course. Across the Disciplines, vol. 12, no. 1, 2015. http://wac.colostate.edu/atd/articles/hardyetal2015.cfm. Accessed 16 May 2019.

Hart, Gwen. ‘Writing is Like Shaping a Bonsai Tree’: Writing about Writing and Culture in a Developmental Composition Course. Bird et al., pp. 97-100.

Hayes, Carol, Ed Jones, Gwen Gorzelsky, and Dana L. Driscoll. Adapting Writing about Writing: Curricular implications of Cross-Institutional Data from the Writing Transfer Project. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 41, no. 2, 2018, pp. 65-88.

Hoover, Kimberly, Elle Limesand, Maggie Hammond, and Max Wellman. Writing about Writing Focus: A Roundtable. Bird et al. pp. 209-19.

Johnson, Frances. A Unique Pair: Pairing WAW in a First-Year Writing Sequence as the First Step in Academic Research. Bird et al. pp. 172-76.

Kleinfeld, Elizabeth. Researching about Research, Writing about Writing from Sources. Bird et al. pp. 177-79.

LaRiviere, Katie Jo. Play the Game But Refocus the Aim: Teaching WAW within Alternative Pedagogies. Bird et al. pp. 261-70.

Looker, Samantha. "Writing about Language: Studying Language Diversity with First-Year Writers." Teaching English in the Two Year College, vol. 44, no. 2, 2016, pp. 176-198.

Lucchesi, Andrew. Engineering Writing about Writing in Engineering: Experiments in Technical Writing and Collaborative Design. Bird et al. pp. 150-54.

Mahaffey, Cat, and Jan Rieman. Developing a Writing about Writing Curriculum. Bird et al., pp. 123-134.

McCracken, I. Moriah, and Valerie A. Ortiz. Latino/a Student (Efficacy) Expectations: Reacting and Adjusting to a Writing-about-Writing Curriculum Change at an Hispanic Serving Institution. Composition Forum, vol. 27, 2013. http://compositionforum.com/issue/27/student-expectations.php.

Moore, Jessie L. and Chris M. Anson. Afterword. In Anson and Moore pp. 331-339.

Mutnick, Deborah. Still ‘Strangers in Academia’; Five Basic Writers’ Stories. Basic Writing e-Journal, vol. 8-9, 2009/2010. https://bwe.ccny.cuny.edu/Still%20“Strangers%20in%20Academia”-%20%20Five%20Basic%20Writers’%20Stories.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Nowacek, Rebecca S. Transfer of Writing-Related Learning. Bird et al., pp. 201-08.

Ogilvie, Andrew. FYC Students as Writing Studies Scholars: Promoting Procedural Knowledge through Participation. Bird et al., pp. 143-45.

Perkins, David. Constructivism and Troublesome Knowledge. Overcoming Barriers to Student Understanding. Jan H. F. Meyer and Ray Land, editors, Routledge, 2006. pp. 33-47.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. Knowledge to Go: A Motivational and Dispositional View of Transfer. Educational Psychologist, vol. 47, no. 3, 2012, pp. 248-58.

---. Transfer of Learning. International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd edition, Pergamon P, 1992, pp. 2-13.

Preface. Essays in Exposition, edited by Benjamin Kurtz, Herbert E. Cory, Frederic Blanchard, and George R. MacMinn. New York: Ginn and Company, 1914, pp. iii-vi, Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?id=42tHAAAAYAAJ. Accessed 29 May 2017.

Read, Sarah, and Michael J. Michaud. Negotiating WAW-PW across Diverse Institutional Contexts. Bird et al., pp. 159-71.

---. Writing about Writing and the Multimajor Professional Writing Course. College Composition and Communication, vol. 66, no. 3, 2015, pp. 427-457.

Robinson, Rebecca. Writing about Writing in the Disciplines in First-Year Composition. Bird et al., pp. 35-46.

Rudd, Mysti. Why I Keep Teaching Writing about Writing in Qatar: Expanding Literacies, Developing Metacognition, and Learning for Transfer. Bird et al., pp. 101-111.

Ruecker, Todd. Reimagining ‘English 1311: Expository English Composition’ as ‘Introduction to Rhetoric and Writing Studies.’ Composition Studies, vol. 39, no.1, 2011, pp. 87-111.

Russell, David R. Activity Theory and Its Implications for Writing Instruction. Reconceiving Writing, Rethinking Writing Instruction, edited by Joseph Petraglia, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1995, pp. 51-78.

Salomon, Gavriel, and David N. Perkins. Rocky Roads to Transfer: Rethinking Mechanisms of a Neglected Phenomenon. Educational Psychologist, vol. 24, no. 2, 1989, pp. 113-42.

Sánchez, Fernando, Liz Lane, and Tyler Carter. Engaging Writing about Writing Theory and Multimodal Praxis: Remediating WaW for English 106: First Year Composition. Composition Studies, vol. 42, no. 2, 2014, pp. 118-146.

Slomp, David H., and M. Elizabeth Sargent. Responses to Responses: Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle’s ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions.’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 60, no. 3, 2009, pp. W25-W34.

Smit, David W. The End of Composition Studies. Southern Illinois UP, 2004.

Smith, Christian, Gabrielle Frick and Patrick Siebel. Podcasting and Protocols: An Approach to Writing about Writing through Sound. Bird et al. pp. 252-60.

Stinson, Samuel. The FYW WAW Composition Classroom Reimagined: Threshold Concepts through Gamification. Bird et al., pp. 180-186.

Thonney, Teresa. Teaching the Conventions of Academic Discourse. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 38, no. 4, 2011, pp. 347-362.

Tremain, Lisa. (Dis)positioning Writing Confidence, Reflecting on Writer Identity. Bird et al., pp. 56-67.

Tuomi-Gröhn, Terttu and Yrjö Engeström, editors. Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Boundary-Crossing. Pergemon, 2003.

---. Conceptualizing Transfer: From Standard Notions to Developmental Perspectives. Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström, pp. 19-38.

Vetter, Matt, and Matthew Nunes. Writing Theory for the Multimajor Professional Writing Course: A Case Study and Course Design. Pedagogy, vol. 18, no. 1, 2018, pp. 157-73. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-4217010. Accessed 25 June 2019.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Creative Repurposing for Expansive Learning: Considering ‘Problem-Exploring’ and ‘Answer-Getting’ Dispositions in Inividuals and Fields. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012. https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/creative-repurposing.php. Accessed 20 June 2019.

Wardle, Elizabeth and Linda Adler-Kassner. Threshold Concepts as a Foundation for ‘Writing-about-Writing’ Pedagogies. Bird et al., pp. 23-34.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and Doug Downs. Looking into Writing-about-Writing Classrooms. First-Year Composition: From Theory to Practice, edited by Debora Coxwell-Teague and Ronald F. Lunsford, Parlor P, 2014, pp. 276-320.

---. Reflecting Back and Looking Forward: Revisiting ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions’ Five Years On. Composition Forum, vol. 27, 2013, https://compositionforum.com/issue/27/reflecting-back.php. Accessed 28 April 2015.

Wells, Jennifer. They Can Get There from Here: Teaching for Transfer through a ‘Writing about Writing’ Course. The English Journal, vol. 101, no. 2, 2011, pp. 57-63.

Wenger, Christy I. Digital Composing in WAW: What Students Learn through Infographics. Bird et al. pp. 234-51.

Wilson, Nancy, Rebecca Jackson, and Valerie Vera. El Ensayo: Latinx Writing about Writing. Bird et al., pp. 88-96.

Winterowd, W. Ross. A Philosophy of Composition. Rhetoric Review, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 340-348.

Axiology and Transfer in Writing about Writing from Composition Forum 45 (Fall 2020)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/axiology.php

© Copyright 2020 John H. Whicker and Samuel Stinson.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 45 table of contents.