Composition Forum 43, Spring 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/43/

Incorporating Visual Literacy in the First-Year Writing Classroom Through Collaborative Instruction

Abstract: This article proposes a model for collaboration between composition instructors and instructional librarians to promote visual literacy instruction in first-year writing courses. While the creation of visual content is essential to digital composing technologies, it often remains underutilized as a tool for writing development in first-year curricula. Drawing from complementary threshold concepts outlined in composition scholarship and the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy, we demonstrate how librarians and writing instructors can engage in collaborative instruction to bridge gaps between theory and practice and leverage existing institutional expertise to support multimodal instruction in first-year writing.

Introduction

In recent years, composition scholars have been engaged in a fundamental disciplinary undertaking: the revitalization of writing pedagogy in light of both expanding definitions of composing and the expansive sites in which writing circulates. Over time, composition studies has turned its attention to writing in all its forms, whether typographical, digital, aural, or visual.{1} In both its scholarship and teaching practices, the field has attempted to balance innovation and reflection in reframing what writing means to (and for) the discipline in the digital age; consequently, the disciplinary work required to respond meaningfully to shifts in composing technologies and the notions of literacy that accompany them remains ongoing.

Clearly, the field’s work has been both enriched and advanced by these efforts. However, of particular interest in this article is the field’s response to a form of literacy at the center of so many digital composing technologies—visual literacy—which, we argue, remains underutilized as a means for addressing the affordances available to student writers, especially in first-year writing (FYW). As Tracey Bowen observes, much student writing remains an exercise in which textual analysis remains dominant and students are infrequently encouraged “to read and remake visual representations with the same level of criticality as they are with written text and language” (710). Research by Aubrey Schiavone analyzing writing prompts in four popular multimodal composition textbooks largely confirms this pattern, concluding that within such texts, “students are prompted to consume visual and multimodal artifacts and to produce textual artifacts” (372). Despite the particularly vital role images play in students’ everyday writing lives, first-year courses too frequently perpetuate pedagogies that recognize the importance of images to textual analysis or critical practice without realizing the full potential of visual composing as a tool for writing development.

This dearth of visual composing in writing classrooms reflects a disconnect between multimodal theory and practice highlighted in the recent collection, Bridging the Multimodal Gap: From Theory to Practice. In their introduction to the volume, Santosh Khadka and J.C. Lee observe that “implementation of multimodal instruction has remained nominal in many writing programs” (4), and that efforts in applying multimodal composing pedagogies to writing curricula remain “sporadic at best” (4). These gaps between theory and practice commonly result from myriad and complex institutional realities, ranging from a lack of access to composing technologies to a lack of training in the assessment of visual or multimodal texts. Addressing such gaps involves marshalling resources and support from multiple campus constituencies, thereby taxing resources and staff in many first-year programs.

Yet we propose that collaboration between instructional librarians and first-year programs can present a practical and effective means to bridge such gaps between theory and pedagogy when it comes to instruction in visual rhetoric and composing strategies. As noted by M. Delores Carlito, librarians have an extensive history of embracing visual literacy as a key component of information literacy, having first established standards for visual literacy instruction in 2011 (203). Their efforts in establishing instructional models for teaching visual literacy demonstrate that “multimodal instruction does not just mean finding an image and using it, but it involves learner-centered production coupled with conscious and thoughtful evaluation” (205). Carolito’s emphasis on the importance of “learner-centered production” in library instruction pairs effectively with models of student writing development central to both multimodal theory and first-year composition pedagogy.

Further, working from principles and practices shared with librarian colleagues can make instruction in visual composing more viable by reducing impediments that too often divide writing theory and teaching practice. For example, first-year programs are frequently limited in terms of funding for technology upgrades and necessary instructional support, as well as restrained by institutional and curricular expectations for what constitutes “good” or “appropriate” features in academic writing. Collaborative partnerships between librarians and first-year programs can often facilitate access to writing and design technologies (software, hardware, production space, publications) that may not otherwise be widely available in standard introductory writing classrooms. Additionally, where “writing instructors and program administrators often feel hard pressed to add yet another unit to an already crowded curriculum” (Handa 9), shared efforts between composition instructors and teaching librarians can be particularly useful in shifting the frame in composition classrooms from the analysis of visuals to the construction and integration of visual content, thereby positioning students more actively within the currents of digital, visual, and rhetorical contexts that inform writing now.

To demonstrate how visual literacy can be incorporated within first-year writing programs through partnerships with instructional librarians, we begin by highlighting shared definitions of visual literacy, presenting an overview of the various ways in which the visual has been defined both generally and in the context of library and information sciences and composition studies, respectively. We then provide recommendations for further defining and communicating shared values through co-instruction of visual composing in FYW, where it can be aligned with visual rhetoric as a branch of both textual analysis and textual production. Finally, we will demonstrate how this model aligns with threshold models advocated in composition scholarship and by the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL), thereby demonstrating how visual literacy can serve as a component of first-year writing practice through which curricular reforms can be enacted.

Visual Literacy & Visual Learning: Initiating the Dialogue

Defining visual literacy remains a challenge due to its interdisciplinary reach and its association with a wide range of intellectual skills. This is prevalent from the beginning when John L. Debes formulated a definition in 1969:

Visual Literacy refers to a group of vision-competencies a human being can develop by seeing and at the same time having and integrating other sensory experiences. The development of these competencies is fundamental to normal human learning. When developed, they enable a visually literate person to discriminate and interpret the visible actions, objects, symbols, natural or man-made, that he encounters in his environment. (14)

This definition casts a wide net, and its complexity is, to some extent, the result of its emphasis on understanding how the visual functions in and across contexts. As such, visual literacy instruction calls for careful development and coordination of sensory, critical, and practical tools required to process visual information across a range of applications. From the start, Debes and others understood that visual literacy took different forms across disciplines as varied as linguistics, philosophy, psychology, psycholinguistics, art, graphic arts, vocational arts, and applied sciences (2-8), resulting in the multidisciplinary lens from which visual literacy is still viewed today.

While this multidisciplinary perspective is valuable to understanding how visual literacy responds to particular contexts and purposes, Maria Avgerinou and John Ericson highlight how this concern for multidisciplinarity works against consensus about the concept’s meaning: “Understandably, the coexistence of so many disciplines underlying the concept of VL [visual literacy] is the major problem in attempting a definition” (283). The vagueness of its definition, the flexibility in its application, and the blurriness of its disciplinary boundaries have contributed to making visual literacy something of a curricular orphan in many college-level curricula. Increasingly relevant to everyone but frequently the responsibility of no one, it holds rich potential for collaborative and cross-disciplinary approaches to instruction.

To realize these potentialities, we suggest building on definitions of visual literacy in library scholarship that readily apply to first-year writing curricula. Most prominently, librarians and composition instructors can agree with Jennifer Brill et al. that images are affordances that convey information or impressions, and that to be visually literate entails not just the ability to interpret (consume or decode) images, but also to create (compose or produce) them (48). Complementary approaches to visual composing shared between instructional librarians and composition teachers therefore offer avenues through which students can generate meaningful and engaging visual content in FYW, honoring students’ capacity to produce material that demonstrates critical understanding of the wide range of rhetorical tools available to writers.

Additionally, in building shared understandings of the value of visual literacy through library partnerships, we gain a wider understanding of how visual literacy correlates with both critical thinking and information literacy (Malamitsa et al. 373-374; Milbourn 277-278; Bowen 707-708), where knowledge gleaned through analysis and creation of visual content can be integrated with existing knowledge (Bowen 708-709). Composition courses can facilitate such integrative learning by offering opportunities for students to explore how visuals can be analyzed, designed, and embedded in texts to suit particular informational needs and fulfill particular purposes. In producing visual content, writers develop new processes for reimagining the rhetorical functions of a texts, prompting composers to reimagine, remix, and revise those functions for new contexts. In this sense, writing instruction can also position visual composing as a tool for invention, in that visuals both draw from and create meaning through their use in particular communities (Palmeri; Denecker). A collaborative approach to visual literacy shared between instructional librarians and composition faculty is therefore well suited to position students as versatile composers capable of communication across a broader spectrum of audiences, communities, and modalities.

By placing greater emphasis on production and use of visual content, library-FYW partnerships guide students toward increasingly complex understandings of the relationships between written language, visuals, and rhetorical concepts because, as noted by Bowen, visual composing “requires analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and prediction within the transformative processes of remaking textual resources,” requiring writers to consider, for example, “what counts as an image, by whom, for whom and by what measures” (710). Library partnerships can help us to pose richer questions about both how visuals come to be—how they are crafted to matter within texts, how they circulate, how they resonate with particular audiences, or how they work in alignment with other forms of composing. Such questions reveal why visual literacy is not just as a set of skills for composing that can be applied to texts, but a hierarchy of knowledge and concepts (Brill et al. 51) that work rhetorically, in relation to audience, purpose, and occasion. By collaborating with instructional librarians in teaching visual composing, we can better emphasize how fundamental principles outlined in the WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition—principles like rhetorical knowledge (e.g. understanding how visuals work in context, and why) and knowledge of conventions (e.g. how visuals make and remake meaning; how that meaning functions within a particular time, audience, or context) —operate across modalities.

This type of deliberate, integrated focus on visual literacy is crucial because instructors often assume that students have mastered a skillset that allows them to successfully navigate and create multimedia landscapes, conflating exposure to visual media with a conscious understanding of how visuals operate rhetorically, or with a working knowledge of how to use them in their academic pursuits. In fact, scholarship in both visual literacy and library sciences indicates students need more targeted learning experiences with both the consumption and creation of multimedia content (Anderson et al. 270-271; Hattwig et al. 64). Library collaborations in FYW can serve to remind instructors and students alike not to mistake familiarity with visual media for proficiency in visual composing—particularly when it comes to informed interpretation, use, design, and integration of data visualization strategies commonly used within academic or professional genres. While we can understand and acknowledge that the visual features prominently in our students’ communicative lives, we must recognize that their daily engagement does not always easily translate to rhetorical knowledge or critical information literacy: it does not necessarily make them savvy consumers of visual content, nor does it indicate a capacity for understanding how rhetorical choices inform the creation of visual content (Lundy and Stephens 1058; Wolfe 345-347; Cappello 733). Further, students come from varied socioeconomic backgrounds and a diverse set of experiences with access, use, and levels of multimedia interactions (Correa 1096-1098), as well as exposure to differing visual genres. Attempting to collaboratively bridge such gaps involves not only questions of definition, practice, and content appropriate for FYW classrooms, but also questions concerning how best to empower students as consumers and producers of visual content in a rapidly changing informational landscape. In the following section, we take up these questions in order to situate visual literacy instruction within a framework for first-year writing, fusing course content and goals.

Visual Literacy and Visual Rhetoric in Composition Courses

For writing instructors, the range of theoretical orientations for making sense of the visual is vast, ranging from theories of rhetoric grounded in both humanistic and social-scientific models, as well as the fine arts. Charles Hill, in “Reading the Visual in College Writing Classes,” observes that this wealth of potential frameworks for visual instruction is, in part, responsible for uncertainty about how and whether to teach the visual in composition: “because visual communication does not yet have a formalized disciplinary framework, we do not even have generally accepted definitions and parameters in which to work” (122). Instead of viewing this complexity as a detriment to meaningful integration of visual literacy in writing classrooms, however, we see this complexity as both an intrinsic motivation and powerful rationale for collaborative instruction between writing instructors and teaching librarians. As noted by Carolyn Handa, “the composition classroom is a proper place to study the visual because visual and verbal literacies have become increasingly interdependent” (4), and this interdependence can ideally be reflected in both our course content and our pedagogical approach when we take up the work of targeted visual literacy instruction in first-year curricula.

Definitions of visual rhetoric that have evolved in the discipline over time can be helpful to review when building an instructional framework for teaching visual literacy in FYW, but they often reflect the consumption/production theory/practice split that collaboration seeks to bridge. For example, in her 2004 article “Framing the Study of Visual Rhetoric: Toward a Transformation of Rhetorical Theory,” Sonja Foss situates the visual within the discipline as follows:

The term, visual rhetoric, has two meanings in the discipline ... It is used to mean both a visual object or artifact and a perspective on the study of visual data. In the first sense, visual rhetoric is a product individuals create as they use visual symbols for the purpose of communicating. In the second, it is a perspective scholars apply that focuses on the symbolic processes by which visual artifacts perform communication. (304)

Foss’s definition—while recognizing visual rhetoric as both something we produce in composing and as an intellectual framework we apply or enact when making sense of others’ written or visual work—tends to emphasize the visual as an object, as the result of an interpretive or composing process. More recently, Kristina Wright, in Show Me What You Are Saying: Visual Literacy in the Composition Classroom, provides a set of definitions that connect the visual to literacy practices, embedding them more fully in a set of processes for interpreting, composing, and communicating rhetorical intent:

Visual Literacy: Fluency in reading, critiquing, and composing with images and image-based media and understanding their influential rhetorical capabilities.

Visual Rhetoric: Communication that uses images or image-based media to persuade or to construct an argument. (47)

Wright’s definition of visual literacy, like Foss’s definition of visual rhetoric, encompasses acts of composing visuals and the use of visual content to fulfill rhetorical goals, though she distinguishes visual rhetoric as the application of visual literacy specifically for persuasive or argumentative purposes. While these definitions reflect established means for teaching visual rhetoric in first-year writing, they also raise questions about whether composition programs have been able to effectively balance responsibility for both analytical and creative elements integral to visual literacy instruction.

Such questions are both valid and fundamental to the kind of collaborative instruction in visual composing we envision for first-year programs. Yet, unfortunately, there is little extensive research that studies the field’s implementation of visual literacy at the ground level (e.g. the number of FYW programs requiring visual rhetoric, the inclusion of visual literacy units in undergraduate or graduate writing programs, etc.). While the Council of Writing Program Administrators revised the WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition (WPAOS) in 2014 to incorporate and encompass new definitions of composing facilitated by digital technologies (see Dryer et al.), few recent surveys of writing programs requiring mulitmodal assignments in FYW have been performed. Those that have been attempted generally predate the 2014 WPAOS revision and are limited in scope and reach.{2} Further, their focus on multimodal (as opposed to visual) composing practice makes a comprehensive snapshot of the field’s implementation of visual instruction in FYW difficult. Surely, many individual writing instructors and some first-year programs have worked to fully integrate visual composing in their first-year curricula. Yet if “we no longer believe that composing processes and composing media are productively distinguished” (Dryer et al. 138), further surveys and research are needed to determine whether that belief has shaped our pedagogical practice meaningfully and systemically.

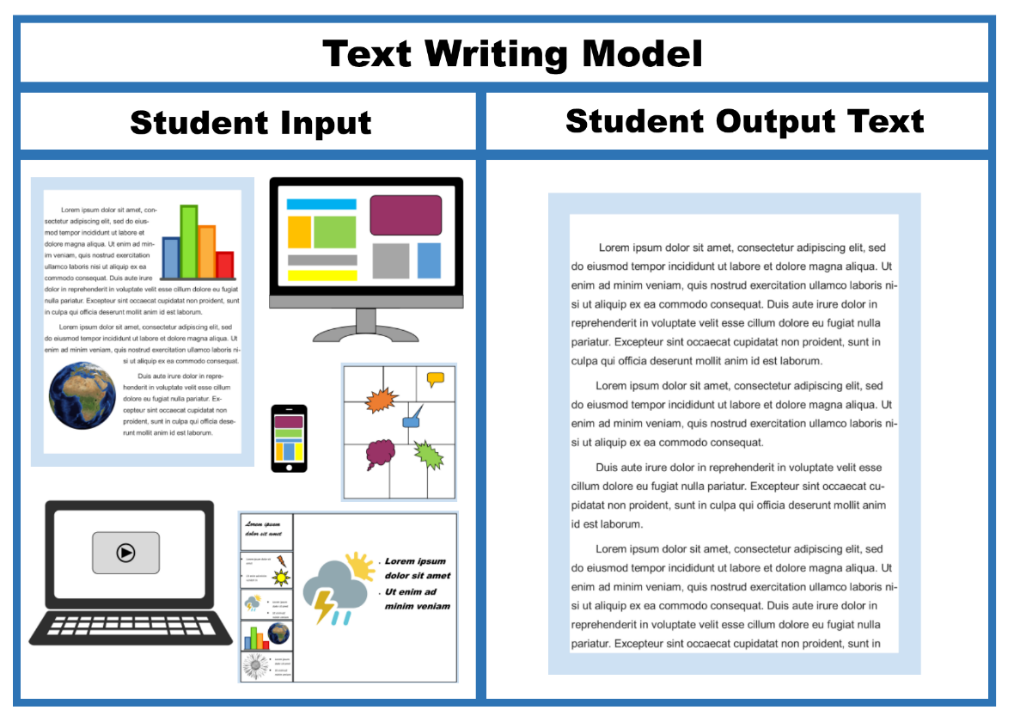

Textbooks{3} offer one limited window for determining whether the field’s theoretical advocacy for visual and multimodal pedagogy (and particularly instruction in the production of visual and multimodal texts) has been fully translated into composition curricula, as noted in Aubrey Schiavone’s analysis of prompts in four central textbooks focusing on visual literacies. Schiavone’s findings indicate that analysis, rather than creation of visual and multimodal content, continues to be emphasized within even those composition textbooks that overtly embrace the use of visual media (371-372): of the 1,629 assignment prompts examined in the study, only 2% required the actual creation of visual content (372){4}. Because, as Schiavone argues, textbooks often comprise a basis for not only assignment design but also curricular design in composition classrooms, this disparity in emphasis between the consumption and creation of visual content “shows a misalignment with theories that argue for an increase in the teaching of visual and multimodal production” (373). If we gather that textbook selection serves as a basis for curricular design—particularly in large FYW programs—Schiavone’s study is one indication that we may not yet be positioning students as flexible, active producers of multimodal or visual content in college writing classes. When we ask students to read and synthesize source texts “made not only in words,” to use Kathleen Blake Yancey’s influential turn of phrase, but then require them to distill information into written text alone (see fig. 1), we insufficiently prepare students to realize and manipulate the affordances available for conveying information in our current informational contexts. And when we fail to offer students opportunities for engaging these contexts using multiple tools, we forgo the task of shaping our writing programs as curricular spaces that foster understanding of relationships among visual content, rhetorical context, and information infrastructures.

Figure 1. Text Writing Model

a. Student Input refers to how students discover and research information for writing assignments using a variety of multimodal resources that incorporate visual media such as articles, webpages, videos, and presentations in both digital and print formats. Student Output Text refers to a single (typographical) mode of creation and dissemination of their writing.

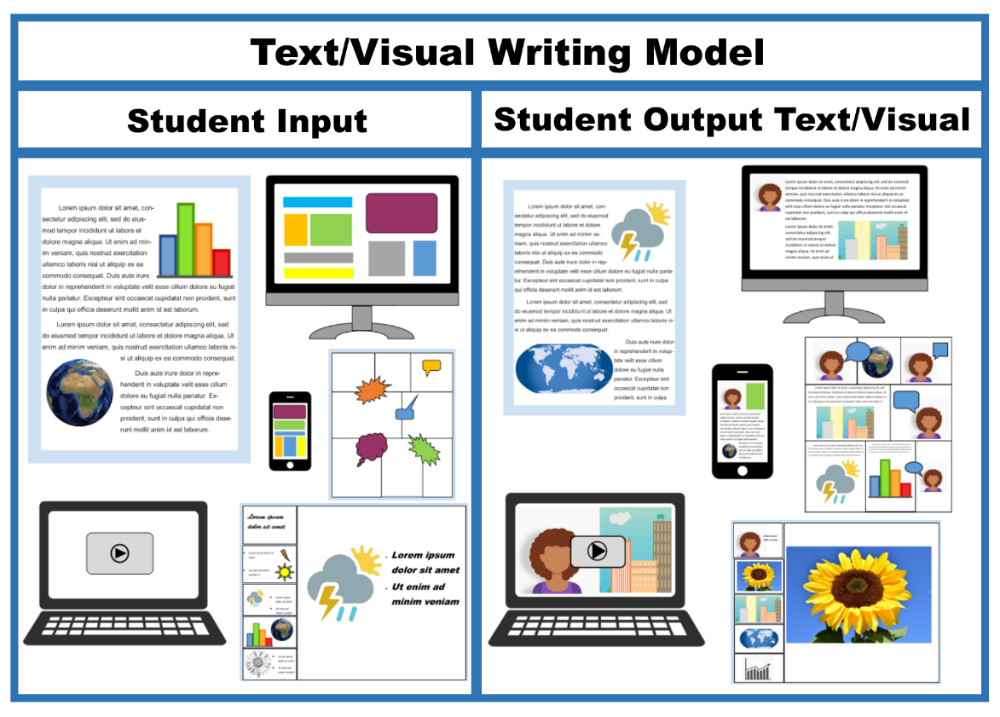

To work more deliberately and collaboratively to build such spaces—spaces in which the content students produce “embraces emerging forms of composing in a world of fluid forms of communication” (Dryer et al. 138)—we locate the roots of our shared vision at a point of intersection between writing studies and library instruction: where visual literacy becomes both a mode of inquiry and a means for invention/intervention students can use to engage the information ecosystems shaping academic, civic, and professional discourse. Further, by asking students to create and disseminate information through both textual and visual modes, we more effectively address the ways in which FYW speaks to knowledge practices embedded in the discipline and beyond. For example, if we wish to see FYW become a site which reflects the definition of composing included in the WPA-OS (3.0), where “writers attend to elements of design, incorporating images and graphical elements into texts intended for screens as well as printed pages” (Dryer et al. 137), then we must offer opportunities for students to engage composing processes and options that move beyond the printed page (see fig. 2).

Figure 2. Text/Visual Writing Model

a. Student Input refers to how students discover and research information for writing assignments using a variety of multimodal resources that incorporate visual media such as articles, webpages, videos, and presentations in both digital and print formats. Student Output Text/Visual refers to their creation and dissemination of writing that reflects the mediums and visuals encountered during the discovery and research phase.

While composition instructors are well positioned to facilitate both critical and productive engagement with visual content, instructional librarians can serve as co-teachers who bring a wealth of knowledge about the nature, influence, and circulation of visual media to the classroom. Guided by developments in collaborative instruction sparked by the publication of the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy, we see potential for such efforts to enhance visual literacy instruction in FYW programs in more deliberate, manageable ways.

Threshold Concepts: A Foundation for Collaborative Visual Literacy Instruction

Recent developments in information literacy and composition studies demonstrate a similar evolution, where both disciplines have shifted from instructional models based in uniform standards to instructional frameworks theorizing threshold concepts as key to student growth. In order to demonstrate how these parallel tracks might converge in teaching visual literacy, we will explore the nature of this shift in information literacy instruction and composition, as well as its relevance to cross-curricular and collaborative initiatives.

The ACRL adopted the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education in 2016. The Framework is based on threshold concepts developed by Meyer, Land, and Baillie and defined as: “Core or foundational concepts that, once grasped by the learner, create new perspectives and ways of understanding a discipline or challenging knowledge domain. Such concepts produce transformation within the learner; without them, the learner does not acquire expertise in that field of knowledge” (qtd. in ACRL, Framework, n3). Building on this concept, the Framework defines information literacy as “the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning” (ACRL,Framework). Designed around six frameworks representing foundational threshold concepts in information literacy—Research as Inquiry, Scholarship as Conversation, Searching as Strategic Exploration, Information has Value, Information Creation as a Process, and Authority is Constructed and Contextual—the Framework is designed to be theoretical in nature, highlighting a set of core concepts without prescribing any specific skill set, performance indicators, outcomes, or standards. It is not a curricular checklist but a starting point for a discussion about the information practices of a community (ACRL, Framework).

In the Framework, information literacy is therefore not based on universal principles and application, but on the idea that interpreting social context is essential to appreciating how information is valued and how that value changes as it moves between contexts. Grounded in a constructivist viewpoint where information is socially constructed and understood by specific communities, the Framework positions students within social contexts where information is made meaningful by communities, shaped by the needs and values shared among community members.

In composition studies, discussions of central goals for writing instruction have also increasingly turned to threshold concepts as a foundation for understanding students’ growth as writers. This shift involves transforming rather objective, skills-based interpretations of instructional outcomes into goals related to conceptual knowledge about writing and its attendant knowledge practices. This revised disciplinary orientation is best evidenced by two projects: the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing (published by CWPA, NCTE, and the NWP in 2011), which frames writing development as the product of habits of mind and experiences with reading, writing, and thinking; and ongoing efforts to define disciplinary threshold concepts, perhaps best represented by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle’s edited collection, Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, which catalogs fundamental, declarative knowledge about writing.

Both the Framework for Success and the threshold concepts outlined in Naming What We Know attempt to shift the field’s vision away from uniform outcomes and toward constructivist, conceptual, and experiential models for learning through and about writing. According to Heidi Estrem, this transformation results, in part, from an evolution in how we understand learning processes, since “as useful as outcomes are, they can’t account for the messy, hard, uneven work of learning. They can provide useful snapshots of end points, of what students are able to do at different curricular moments” (“Threshold Concepts” 93), but they cannot fully account for the constellation of fundamental knowledge that drives writing practices over time, nor for the ways in which that knowledge changes, grows, and is shaped in various contexts for writing.

These disciplinary adoptions of frameworks as a basis for understanding knowledge development create a space for a collaborative instruction since, “a threshold concepts framework offers a particularly powerful way to begin documenting what student learning looks like and to develop a shared, cross-disciplinary vocabulary that might support meaningful student writing development over time” (Estrem,“Threshold Concepts” 96). Working together, composition instructors and instructional librarians are well positioned to create shared ground for incorporating visual literacy within FYW. Indeed, one of the recommendations the ACRL suggests for implementing the Framework is for librarians and faculty to both consider the knowledge practices in their learning communities and seize opportunities to help students recognize themselves as both consumers and producers working within literate contexts (ACRL, Framework). Because there are not predetermined standards in the Framework that dictate curricular design, instructors can collaborate with librarians to determine what threshold concepts related to visual literacy can best be addressed and implemented within the course in its local context, in order to help students become more critical consumers and producers of visual information.

From Threshold Concepts to Common Ground: Aligning the Framework and Writing Thresholds in First-Year Writing Course Work

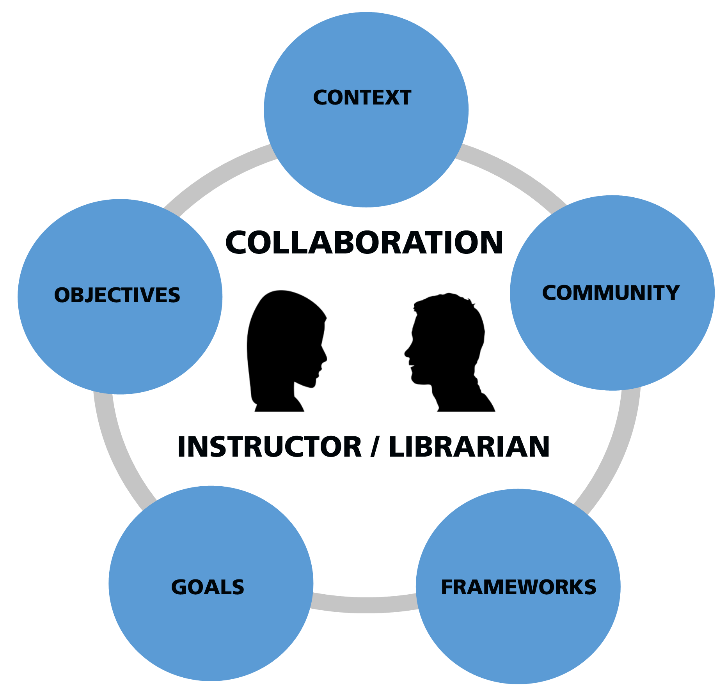

Instructional librarians approach collaborations with teaching faculty both to support the faculty and to promote students’ development. Conversations with composition instructors are essential to instructional librarians in building shared instructional values that empower students to apply what they learned in the context of the discipline and to suit course and assignment goals. Key elements of this collaboration (see fig. 3) would include looking at the information literacy frameworks and identifying which threshold concepts relate to visual composition and visual literacy for particular writing assignments. In this way, instructors can determine which written and visual elements apply to the writing context and discourse community, the level of instruction needed to convey fundamental concepts required of each assignment, and how the instructional librarians could best support composition instructors in the teaching of those concepts.

Figure 3. Implementing Threshold Concepts Through Instructor/Librarian/Student Collaboration

Those who teach FYW have already begun the work of mapping threshold concepts relevant to writing instruction to the frames outlined in the Framework for Information Literacy (see, for example, collections by Adler-Kassner and Wardle, Baer, D’Angelo et al., and Veach, as well as Johnson and McCracken). These types of discussions create rich opportunities for incorporating visual literacy into existing conversations about shared goals. To demonstrate how this might work in practice, let us take as a starting point two concepts from the Framework for Information Literacy that can be readily applied to visual literacy—“Authority is Constructed and Contextual” and “Information Creation as a Process”—and align them with writing threshold concepts to show how this can play out.

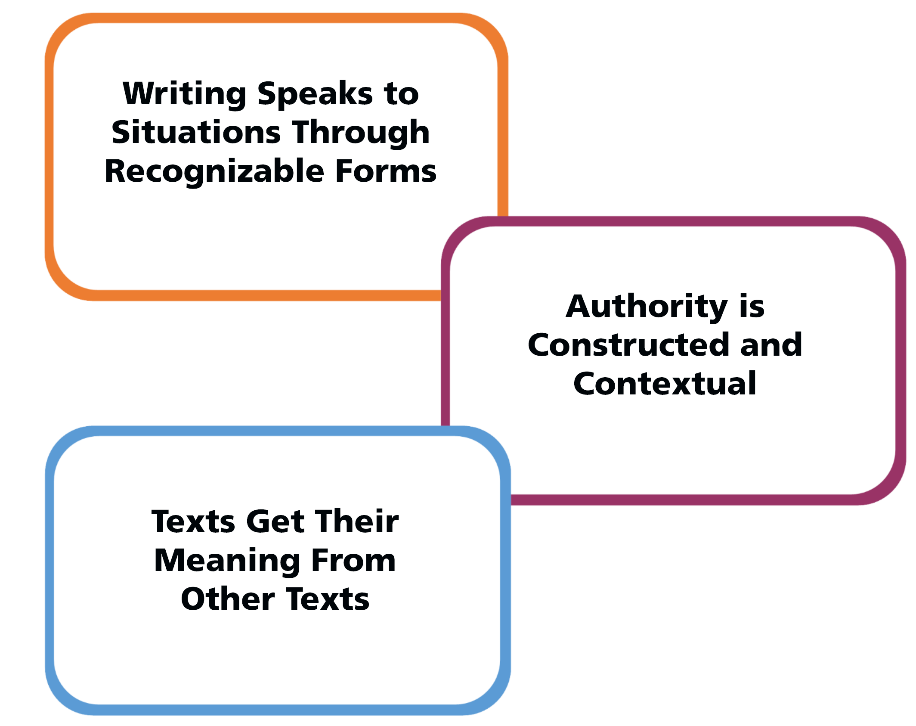

Adler-Kassner and Wardle’s collection (Naming What We Know) presents a number of relevant threshold concepts, yet two serve as particularly viable starting points: “Writing Speaks to Situations Through Recognizable Forms” (Bazerman 35-37) and “Texts Get Their Meaning From Other Texts” (Roozen 44-47) align well with the ACRL Framework’s “Authority is Constructed and Contextual” (see fig. 4). Composition instructors recognize that “Writing Speaks to Situations Through Recognizable Forms,” and it does so in ways that are always influenced by authority, shaped by the rhetorical situation, enacted through genres, and located within a community (Bazerman 35-37).

Figure 4. Complementary Writing and Information Literacy Concepts

From the perspective of the Framework, the influence of authority is encoded in texts through the types of evidence utilized within communities of practice and both determined and interpreted through “questions of origins, context, and suitability for the current information need” (ACRL Framework). Librarians and writing instructors share this recognition of purpose, appropriateness, and credibility in teaching students about the rhetorical situation and in holding students accountable for building (or resisting) such forms of authority in their visual composing practices.

We can also build on conversations regarding textual authority through attention to concepts like genre knowledge. Librarians bring a wealth of expertise in a wide range of genres to instruction of first-year students, and, more importantly, a deep awareness of the systems that define their classification, circulation, and use. In discussing how authority is constructed in ways that draw “reflective attention through the concepts of rhetorical situation, genre, and activity systems” (Bazerman 37), we can better facilitate students’ capacity to work with visual content in collaboration with librarians. Because instructional librarians can expertly demonstrate how authority is built, sustained, and distributed through information systems, they can also provide guidance and insight as students design visual content in ways that are responsive to the networks of meaning shared in a given community. For example, a session on converting data and statistics to a visual format could include understanding the strengths and weaknesses of particular types of graphs, which types of graphs are used in different disciplines and professions, which tools can be used to create graphs, and how the output medium can influence the choice and style of graph (i.e. static or interactive). It is clear that in developing this “reflective attention” to how authority is shaped verbally, visually, and through genres, we can also help students to better understand that “Texts Get Their Meaning From Other Texts.” As noted by Kevin Roozen, this threshold concept calls attention to the ways in which “texts always refer to other texts and rely heavily on these texts to make meaning” (44). This principle is also clearly communicated in the ACRL Framework’s knowledge practices—and particularly in its goal of helping students to better understand “the increasingly social nature of the information ecosystem where authorities actively connect with one another and sources develop over time.” Again, we can easily see how activities supported by the Framework—whether examination of an author’s use of sources or in designing database searches around an author’s textual or visual references—can illuminate the ways in which networks of meaning are constructed by writers and both reconstructed and remade by knowledgeable readers.

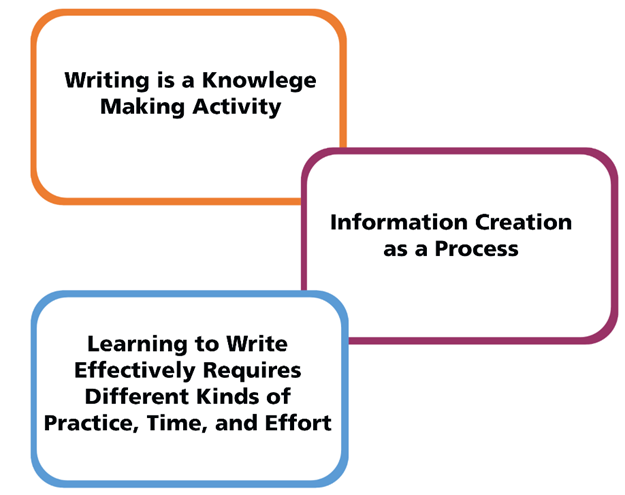

Another effective pairing of threshold concepts from both writing and information literacy that can be used to integrate visual composing within first-year classes is relating the threshold concepts “Writing Is A Knowledge-Making Activity” (Estrem 19-20), and “Learning to Write Effectively Requires Different Kinds of Practice, Time, and Effort” (Yancey 64-65) with the ACRL’s “Information Creation as a Process” (see fig. 5).

Figure 5. Complementary Writing and Information Literacy Concepts

“Information Creation as a Process” highlights concepts and activities that foster composition’s emphasis on the importance of writing processes in the creation and revision of information. As such, it aligns both philosophically and practically with one of the threshold concepts most frequently referenced in first-year composition classrooms: “Writing is a Knowledge-Making Activity” (Estrem 19-20). In her chapter on this concept, Estrem highlights the significance of understanding writing as an active force in creating meaning, not just communicating it, noting that “writing in this sense is not about crafting a sentence or perfecting a text but about mulling over a problem, thinking with others, and exploring new ideas or bringing disparate ideas together” (“Writing” 19). Central to this activity is the discovery, exploration, and revision of ideas: the act of research and hence commonly the domain of information literacy. Indeed, in speaking of the theoretical grounding of the Framework for Information Literacy, Nancy Foasberg highlights this symmetry of purpose with composition, observing, “these frames promote an understanding of information as writing—as original work that someone has created in a specific context, which students need to understand as they respond to the writing” (709). Working collaboratively to communicate this reality is the driving force behind the Framework and the reason for its particular relevance to writing instruction.

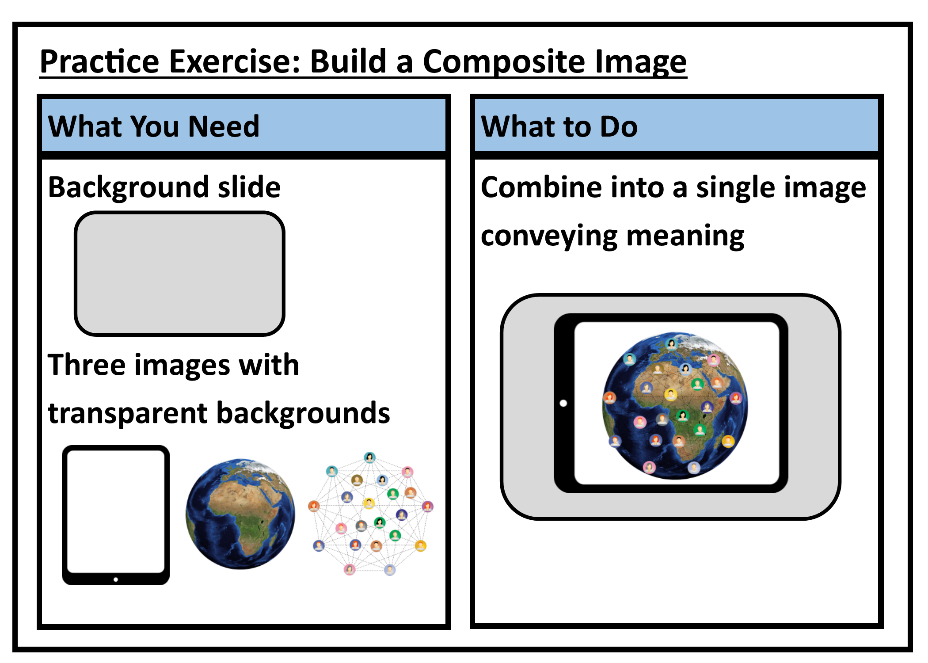

Of course, we would add that visual communication is also writing, and helping students to understand the process of information creation as it relates to visual content is increasingly important to students’ understanding of “the capabilities and constraints of information developed through various creation processes” (ACRL Framework). This ties into “Learning to Write Effectively Requires Different Kinds of Practice, Time, and Effort” (Yancey 64-65). In developing strategies to not only help students interpret “the capabilities and constraints of information” offered by typographical and visual texts, but also to help them make meaningful choices in working within such constraints, instructors and librarians can assist students through collaborative practice. As Yancey notes, writing practice should take on “different spaces, with different materials, and with different technologies” (“Learning” 64) in order to broaden students’ options and capabilities as writers. Converting an idea expressed typographically into an idea expressed visually often requires just such practice and problem solving, engaging the student in a process of knowledge making as they create visual representations of meaningful information. In particular, Yancey emphasizes the importance of “differentiated practice across different spaces of writing, working with different technologies of writing” (“Learning” 65)—including visual spaces. Teaching librarians, whose work transcends disciplinary spaces and helps students to establish cross-disciplinary approaches to the discovery, organization, and dissemination of information, are well equipped to introduce students to visual composing technologies and to facilitate engagement with visual media. For example, the PowerPoint presentation (or versions of it such as lightning talks or the Pecha-Kucha) is a common type of multimodal writing that too often leads users to revert to typographical composing instead of capitalizing on the software’s visual composing capabilities. Librarians can assist students in learning how to use the necessary tools to create their PowerPoint presentations focusing on visuals with limited or no typographical text, as well as tools to help them find appropriate visuals (including public domain and creative commons images) or create the visuals themselves (for example, all visuals in this paper were created by the authors using public domain or no- attribution licensed images and common software available to students and faculty).

Creating flexible, yet discipline-based frameworks for understanding the linkages, connections, and conventions of the ever-shifting information landscape grows out of the ACRL’s assertion that “teaching faculty have a greater responsibility in designing curricula and assignments that foster enhanced engagement with the core ideas about information and scholarship within their disciplines” (ACRL Framework). Yet such efforts are enhanced when paired with teaching librarians’ “greater responsibility in identifying core ideas within their own knowledge domain that can extend learning for students.” Working in collaboration, librarians can assist writing faculty in planning visual assignments that align with course goals and objectives; assist with scaffolding visual literacy instruction; identify visual composing tools and related instructional content; and develop communities where students explore and create visual information together (Little 87-91) Because the domain of visual literacy extends beyond discipline-specific contexts, taking a reflective, reciprocal, and collaborative approach to its instruction can allow us to both offer “enhanced engagement” with visual content and “extend learning” in ways suitable to first-year instruction, thereby building more comprehensive and inclusive first-year curricula.

Incorporating Visual Literacy Through Shared Instruction

Finally, central to our understanding of how the Framework can be utilized in teaching visual literacy in FYW is the document’s overview of the relevance of metaliteracy to understanding the informational landscape. In establishing its vision of literacy and learning, the ACRL Framework “draws significantly upon the concept of metaliteracy, which offers a renewed vision of information literacy as an overarching set of abilities in which students are consumers and creators of information.” Clearly, this recognition of the need for students to develop as both consumers and creators of information is a key thread that binds the aims of composition instructors and their librarian colleagues, and it is a central tenet required when making space for visual literacy within FYW. But perhaps more important to developing productive visual composing pedagogies is the ACRL’s understanding of metaliteracy as fundamental to informed participation in both academic and everyday discourse:

Metaliteracy expands the scope of traditional information skills (determine, access, locate, understand, produce, and use information) to include the collaborative production and sharing of information in participatory digital environments (collaborate, produce, and share). This approach requires an ongoing adaptation to emerging technologies and an understanding of the critical thinking and reflection required to actively engage in these spaces.

(Mackey and Jacobson, qtd. in ACRL Framework, n7)

With metaliteracy as a common denominator shared with librarians, composition instructors can better teach the web of rhetorical relationships that determine context, consumption, production, and distribution of research in ways that transfer across contexts. As Wardle argues, “meta-awareness about writing, language, and rhetorical strategies in FYC may be the most important ability our courses can cultivate,” and that role compels us to “help [the] student think about writing in the university, the varied conventions of different disciplines, and their own writing strategies in light of various assignments and expectations” (82). Because the ACRL model emphasizes metaliteracy and reflection as key components of understanding, composing, and sharing information across disciplinary contexts, it may also help us to shift our attention to what Aubrey Schiavone calls “a reciprocal positioning of consumption and production” in our pedagogy, one in which both processes are “necessarily interconnected, rather than separate from one another” (366).

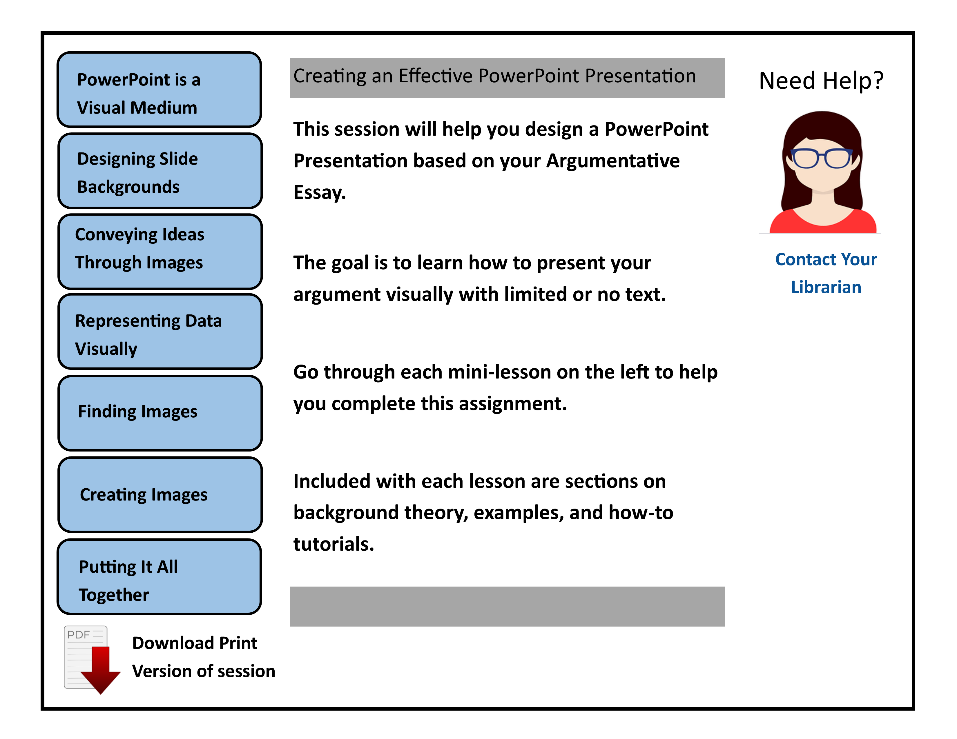

Library partnerships facilitate this repositioning while highlighting and enacting the interconnectedness of concepts underlying metaliteracy and multimodal approaches to instruction. Yet there is also a pragmatic advantage in sharing the instructional load for visual literacy instruction with librarians. As noted previously, one of the more difficult tasks for writing instructors is to add responsibility for visual literacy instruction to an already crowded curriculum. Yet, according to Nerissa Nelson, “instruction, both formal and informal, has always been a function of librarians whether it is direct or indirect, within or outside the classroom, a ‘one shot’ session or a full-credit course” (7). Librarians’ familiarity with formal and informal forms of instruction can prove valuable in offering avenues for integration of visual literacy concepts in the first-year writing curriculum. For example, visual literacy instruction can be incorporated into existing formal library research instruction (especially in the identification and use of visuals in the forms of research students explore). These formal sessions could be individual “one-shot” sessions, a series of sessions utilizing instructional scaffolding, a series of mini-lessons (20 minutes or less) throughout the term, or a combination of these models. The sessions lend themselves to both face-to-face and online writing courses with or without the librarian embedded in the course management system as a non-grading instructor. As demonstrated in figures 6.1-6.3, librarians can also develop online, assignment-specific content to support instruction of writing concepts and assist with the production of visuals in students’ writing outside of the classroom by developing self-guided online content to introduce students to concepts and strategies for image creation. Additionally, holding individual conferences with students to help them with visual content (much as students come to a librarian for help conducting research and finding relevant scholarship) can extend instruction in ways that promote students’ ability to gain differentiated practice.

Figure 6.1. Example of an Assignment-Specific Visual Literacy Instruction for FYW

a. This is an example of a librarian created tutorial working collaboratively with the writing instructor to assist students in converting a previous written text/visual assignment (argumentative essay) into a primary visual/text assignment{5}.

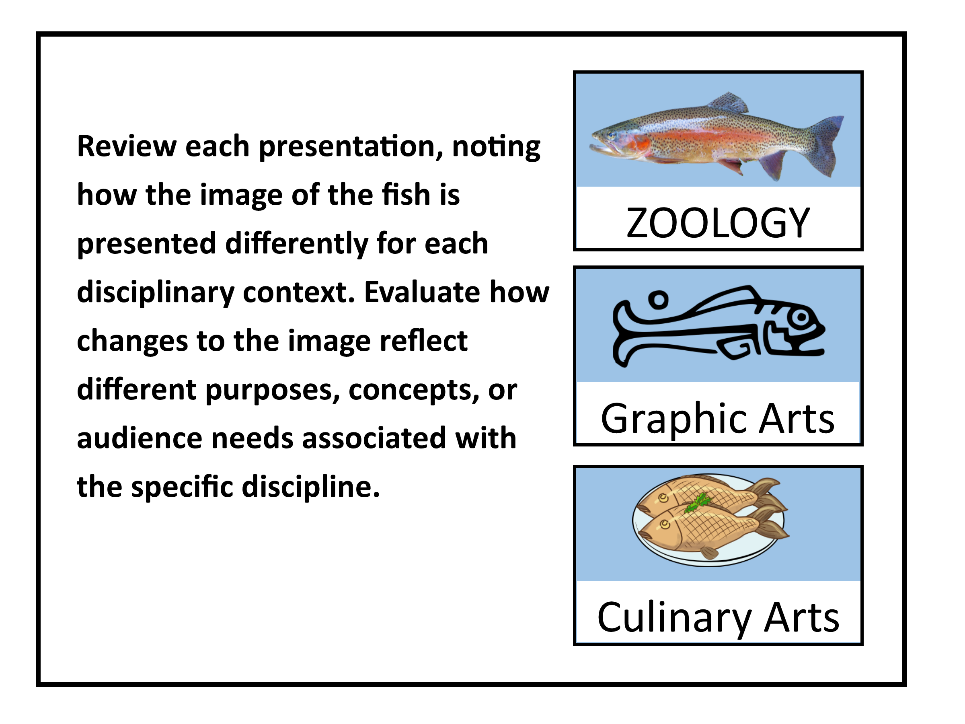

Figure 6.2. Example of a Visual Literacy Activity from the Conveying Ideas Through Images Portion of the Tutorial

a. This is an example of how writing and information literacy concepts (“Writing Speaks to Other Situations through Recognizable Forms,” “Authority is Constructed and Contextual,” and “Texts Get Their Meaning from Other Text”) manifest in practical instruction. See also fig. 4: Complementary Writing and Information Literacy Concepts.

Figure 6.3. Example Visual Literacy Activity from the Creating Images Portion of the Tutorial

a. This is an example of writing and information literacy concepts (“Writing is a Knowledge Making Activity,” “Information Creation as a Process,” and “Learning to Write Effectively Requires Different Kinds of Practice, Time, and Effort”) manifest in practical instruction. See also fig. 5: Complementary Writing and Information Literacy Concepts.

In “A Pragmatic and Flexible Approach to Information Literacy” Barbara Junisbai, M. Sara Lowe, and Natalie Tagge note that with moderate collaboration on course assignments and learning outcomes, it only requires one or two targeted library sessions to produce significant gains in information literacy without teaching faculty having “to completely retool their course” (608-609). Building upon threshold concepts, collaborative instruction design, and metaliteracy, visual literacy can be incorporated into FYW assignments with only minor changes to an existing course.

Conclusion

Both composition instructors and instruction librarians have built common ground by tracing the cross-currents that emerge when we juxtapose pedagogical models for teaching writing with those for teaching information literacy. Working collaboratively, librarians and writing instructors are poised to help students critically navigate both visual and typographical composing processes. Just as important, however, is the potential for this shared attention to visual literacy instruction to assist students in seeing writing and its role in a different light. Positioning visual literacy in FYW—at the threshold of college-level research and composing practice—may help to expand student conceptions of writing at a pivotal point.

By designing first-year experiences with visual composing, we engage students directly in the work of constructing authority in ways that may deviate from formulas they often associate with academic prose and offer a different type of practice in constructing that authority. Actively engaging students in seeing writing differently has great potential. Visual literacy—with an emphasis on the production and integration of visual media as/in writing—offers opportunities for experiential learning students will need outside of the writing classroom.

Sharing responsibility for supporting students in this process of transformation encourages us to model what composing means across communities of practice, affirming our collective belief that contextual understanding and rhetorical versatility is crucial to empowering students in their literate lives and development.

Notes

-

We use the term “typographical” to denote forms of writing that utilize the conventions of traditional (printed) academic text in both their modes of production (typed or handwritten) and in their overall appearance and arrangement (text-heavy, linear, left-justified, essayistic, etc.). We use this term, as opposed to “written,” because we see writing as inclusive of many forms of composing tools and styles, whether visual, digital, audio, or textual. (Return to text.)

-

Examples of surveys of multimodal practices in FYW include a 2009 report by Campbell et al. on the implementation of multimodal assignments at the University of Denver, and a 2013 Computers and Writing Conference session on Undergraduate Curricula and Multimodal Composing presented by Cornelius, Lee, Sheridan, and Odell and reviewed by Sarah Spring. (Return to text.)

-

In this case, textbooks that, in Schiavone’s terms, “purport to engage visual elements, rather than textbooks that take multimodal composition as their primary goal” (363). (Return to text.)

-

Schiavone distinguishes between visual and multimodal production in her work, recognizing that multimodal assignments may or may not include visual elements in their composition. Of the textbooks examined, “11 percent prompt the production of a multimodal artifact, while 36 percent of assignments prompt the production of a textual artifact” (372). (Return to text.)

-

This tutorial is presented in a linear configuration. Learning/Content Management Systems such as Moodle, Blackboard and LibGuides have a limited structure that dictates how information is presented. The advantage of using these systems for tutorials is they are easy to add and build content within the structure and do not require any sophisticated technology skills while minimizing the time needed to create content. This does not replicate the fluid nature of the writing/creating visuals process, but they have the advantage of segmenting important concepts and ideas. Activity slides and assignments can be incorporated to reinforce the concepts and encourage practice. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle, editors. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. UP of Colorado, 2015.

Anderson, Elizabeth K., et al. Teaching Visual Literacy: Pedagogy, Design and Implementation, Tools, and Techniques. Essentials of Teaching and Integrating Visual and Media Literacy, edited by Danilo M. Baylen and Adriana D’Alba, Springer International Publishing Switzerland, 2015, pp. 265-290.

Association of College & Research Libraries. Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. 11. Jan. 2016, http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework.

Avgerinou, Maria and John Ericson. A Review of the Concept of Visual Literacy. British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 28, 1997, pp. 280-291.

Baer, Andrea. Information Literacy and Writing Studies in Conversation: Reenvisioning Library-Writing Program Connections. Library Juice Press, 2016.

Bazerman, Charles. Writing Speaks to Situations through Recognizable Forms. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 35-36.

Brill, Jennifer M., et al. Visual Literacy Defined–The Results of a Delphi Study: Can IVLA (Operationally) Define Visual Literacy? Journal of Visual Literacy, vol. 27, no.1, 2007, pp. 47-60.

Bowen, Tracey. Assessing Visual Literacy: A Case Study of Developing a Rubric for Identifying and Applying Criteria to Undergraduate Student Learning. Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 22, no. 6, 2017, pp. 705-719.

Campbell, Jennifer, et al. Creating a Multimodal Element in WRIT Courses at the University of Denver. Report of the Multimodal Study Group. 3 Sept. 2009, https://portfolio.du.edu/downloadItem/188095.

Cappello, Marva. Considering Visual Text Complexity: A Guide for Teachers. The Reading Teacher, vol. 70, no. 6, 2017, pp. 733-739.

Carlito, M. Delores. Creating a Multimodal Argument: Moving the Composition Librarian Beyond Information Literacy. Teaching Information Literacy and Writing Studies: Volume 1 First-Year Composition Courses, edited by Grace Veach, Purdue UP, 2018, pp. 199-212.

Correa, Teresa. Digital Skills and Social Media Use: How Internet Skills are Related to Different Types of Facebook Use Among ‘Digital Natives’. Information, Communication & Society, vol.19, no. 8, 2016, pp. 1095-1107.

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project. Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing. 9 Feb. 2011, https://www.nwp.org/cs/public/print/resource/3479.

Council of Writing Program Administrators. WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition (3.0). July 2014, http://wpacouncil.org/positions/outcomes.html.

D’Angelo, Barbara, et al., editors. Information Literacy: Research and Collaboration Across Disciplines. The WAC Clearinghouse, 2016, https://wac.colostate.edu/books/infolit/collection.pdf.

Debes, John L. The Loom of Visual Literacy -- An Overview. Proceedings First National Conference on Visual Literacy, March 1969, edited by Clarence M. Williams and John L. Debes, Pitman Publishing, 1970, pp. 1-16.

Denecker, Christine. Digital Heuristics: By Chance and By Choice. Computers and Composition Online, Spring 2010, http://cconlinejournal.org/Digital_Heuristics/.

Dryer, Dylan, et al. Revising FYC Outcomes for a Multimodal, Digitally Composed World: The WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition (Version 3.0). WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 38, no. 1, 2014, pp. 129-143.

Estrem, Heidi. Threshold Concepts and Student Learning Outcomes. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 89-104.

Estrem, Heidi. Writing is a Knowledge-Making Activity. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 19-20.

Foasberg, Nancy M. From Standards to Frameworks for IL: How the ACRL Framework Addresses Critiques of the Standards. portal: Libraries and the Academy, vol. 15, no. 4, 2015, pp. 699-717.

Foss, Sonja K. Framing the Study of Visual Rhetoric: Toward a Transformation of Rhetorical Theory. Defining Visual Rhetorics, edited by Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004, pp. 303-313.

Handa, Carolyn. Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Source Book. Bedford/St. Martins, 2004.

Hattwig, Denise, et al. Visual Literacy Standards in Higher Education: New Opportunities for Libraries and Student Learning. portal: Libraries and the Academy, vol. 13, no.1, 2013, pp. 61-89.

Hill, Charles A. Reading the Visual in College Writing Classes. Intertexts: Reading Pedagogy in College Writing Classrooms, edited by Marguerite Helmers, Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, 2003, pp. 118-143.

Johnson, Brittney and Moriah McCracken. Reading for Integration, Identifying Complementary Threshold Concepts: The ACRL ‘Framework’ in Conversation with ‘Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing’. Communications in Information Literacy, vol.10, no. 2, 2016, pp.178-198.

Junisbai, Barbara, et al. A Pragmatic and Flexible Approach to Information Literacy: Findings from a Three-Year Study of Faculty-Librarian Collaboration. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, vol. 42 no. 5, 2016, pp. 604-611.

Khadka, Santosh, and J.C. Lee, editors. Bridging the Multimodal Gap: From Theory to Practice. Utah State UP, 2019.

Little, Deandra. Teaching Visual Literacy Across the Curriculum: Suggestions and Strategies. Looking and Learning: Visual Literacy Across Disciplines, edited by Deandra Little, et al., Jossey-Bass, 2015, pp. 87-90.

Lundy, April D., and Alice E. Stephens. Beyond the Literal: Teaching Visual Literacy in the 21st Century Classroom. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 174, 2015, pp. 1057-1060.

Mackey, Thomas P. and Trudi E. Jacobson. Metaliteracy: Reinventing Information Literacy to Empower Learners. Neal-Schuman, 2014.

Malamitsa, Katerina, et al. Graph/Chart Interpretation and Reading Comprehension as Critical Thinking Skills. Science Education International, vol. 19, no. 4, 2008, pp. 371-384.

Meyer, Jan H.F., et al. Editors Preface. Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning, edited by Jan H.F. Meyer, Ray Land, and Caroline Baillie, Sense Publishers, 2010, pp. ix-xlii.

Milbourn, Amanda. A Big Picture Approach: Using Embedded Librarianship to Proactively Address the Need for Visual Literacy Instruction in Higher Education. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, vol. 32 no. 2, 2013, pp. 274-283.

Nelson, Nerissa. Visual Literacy and Library Instruction: A Critical Analysis. Education Libraries, vol. 27, no.1, 2004, pp. 5-10.

Palmeri, Jason. Remixing Composition: A History of Multimodal Writing Pedagogy. Southern Illinois UP, 2012.

Roozen, Kevin. Texts Get Their Meaning from Other Texts. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 44-47.

Schiavone, Aubrey. Consumption, Production, and Rhetorical Knowledge in Visual and Multimodal Textbooks. College English, vol. 79 no. 4, 2017, pp. 358-380.

Spring, Sarah. Review: Undergraduate Curricula and Multimodal Composing Presentation with Panelists Kristin Cornelius, Rory Lee, David Sheridan, Lee Odell at Session g1 at the Computers & Writing Conference 8 June 2013. DRC: Digital Rhetoric Collaborative, 2 Aug. 2013, http://www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/2013/08/02/undergraduate-curricula-and-multimodal-composing-session-g1/.

Veach, Grace. Teaching Information Literacy and Writing Studies Volume 1: First-Year Composition Courses. Purdue UP, 2018.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Understanding ‘Transfer’ from FYC: Preliminary Results of a Longitudinal Study. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no. 2, 2007, pp. 65-85.

Wolfe, Joanna. Teaching Students to Focus on the Data in Data Visualization. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 29, no. 3, 2015, pp. 344-359.

Wright, Kristina. ‘Show Me What You Are Saying’: Visual Literacy in the Composition Classroom. Visual Imagery, Metadata, and Multimodal Literacies Across the Curriculum, edited by Anita August, IGI Global, 2018, pp. 24-49.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. Learning to Write Effectively Requires Different Kinds of Practice, Time, and Effort. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 64-66.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key. CCC, vol. 56, no. 2, 2004, pp. 297-328.

Incorporating Visual Literacy from Composition Forum 43 (Spring 2020)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/43/visual-literacy.php

© Copyright 2020 Erica Frisicaro-Pawlowski and Robert Monge.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 43 table of contents.