Composition Forum 43, Spring 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/43/

Student-Athletes’ Metacognitive Strategy Knowledge

Abstract: This article reports findings from a single-bounded case study on student-athletes’ performance of what educational psychologist Yves Karlen refers to as metacognitive strategy knowledge (MSK) in two first-year composition assignments. This case study is focused on the following research question: how might the promotion of MSK in a FYC class support the development of student-athletes’ writing skills? Data collection includes semi-structured, in-person interviews, visual and bodily mapping exercises, and textual analysis of research participants’ academic writing. This essay offers a two-pronged argument based on the data. First, promoting the development of MSK through established composition and rhetoric writing assignments dovetails with student-athletes’ athletic literacy and supports their development as academic writers. Second, student-athletes’ prior knowledge and practice of metacognition helps instructors gain a stronger understanding of how they may use MSK to facilitate future writing assignments.

I arranged six student-athletes around the basketball court in the gym at the University of North Georgia. Nineteen additional students sat in the stands waiting their turn. A baseball player stood at one baseline of the court holding a basketball. A cross-country runner stood 94 feet away on the other baseline. A softball player at the three-point line, two soccer players at midcourt, and a baseball player at the other three-point line.

“Ok,” I shouted in the cavernous basketball arena, my voice bouncing off the rafters, stands, and court. “Let’s try this.”

It was late October, about midway through the semester. For the first nine weeks, we stayed in the classroom undertaking common writing activities. But this class was different. And I needed to try something different. For nine weeks, I had put it off because I was not sure what would happen.

But here we were. Twenty-five student-athletes, one dual-enrolled student, and me.

“Let’s visualize writing this way,” I said and verbally explained the physical drill, my voice weakening as I shouted. I pointed to the baseball player with the basketball.

“Go!”

And he went.

With the support of the athletics director and faculty athletics representative at the University of North Georgia (UNG), I designed and taught one section of first-year composition (FYC) populated by twenty-five student-athletes and one dual-enrolled student. In this essay, I report findings from a single-bounded case study on student-athletes’ performance of what educational psychologist Yves Karlen refers to as metacognitive strategy knowledge. I focus on their performance of MSK in two FYC writing assignments. In brief, MSK details two cognitive activities associated with metacognition: conditional strategy knowledge and relational strategy knowledge. The first helps writers think about when and why to deploy specific writing strategies or rhetorical moves; the second, helps writers think how these strategies and moves are alike and different.

I turn attention to student-athletes in this case study because of their extracurricular textual experiences and the role metacognition plays in these experiences. Like our student thespians and musicians, student-athletes give bodily expression to written texts (Cheville; Rifenburg, “Writing as Embodied”). In the student-athletes’ case, these written texts are not lines or musical notes but sports’ plays. Student-athletes know through their body. Their extracurricular athletic literacy shapes their academic literacy, particularly when they engage with texts in writing-intensive academic spaces, like FYC. Additionally, student-athletes’ athletic literacy includes broad, structured experience with metacognition. Most college athletic performances—be it a practice or a game—are filmed and watched by players and coaches to refine future athletic performance.

When I spent one season embedded in the men’s basketball team at UNG, I sat with the players in a classroom as the coach showed film of their previous game (Rifenburg, The Embodied Playbook). Around me, student-athletes sat behind and on desks, watching their performance. The head coach paused the tape, asked questions, heard responses, made notations with a black marker on the whiteboard. Before an away game, I sat with three players as the assistant coach played a tape of the opponent and highlighted tendencies the opposition and players on the opposition possessed. The coaches taught material in response to the past and in preparation for the future. Our student-athletes enter writing-intensive academic spaces with a broad understanding of and experience with reflecting on past performance. However, they do not enter our classrooms with detailed understandings of the different types of metacognition that we get from MSK.

I approach this case study with a single research question: how might the promotion of MSK in a FYC class support the development of student-athletes’ writing skills? Based on my data, I offer a two-pronged argument. First, promoting the development of MSK through common rhetoric and composition writing assignments dovetails with student-athletes’ current athletic literacy—a literacy already driven by structured moments of broad application of metacognition—and supports their development as academic writers. Second, student-athletes’ prior knowledge and practice of metacognition can help instructors gain a stronger understanding of how they may use MSK to support future writing assignments. This reciprocal argument, wherein both student-athletes and instructors gain knowledge, drives this essay. To illustrate this argument, I introduce three male baseball players at UNG whom I worked with in English 1102, the FYC class largely populated by student-athletes. Data collection includes semi-structured, in-person interviews, visual and bodily mapping exercises, and textual analysis of research participants’ English 1102 writing in response to two assignments.

Method

Responding to my research question, I designed a single-bounded case study. I bounded the case spatially (one English 1102 course at UNG) and temporally (Spring 2017). Case study research hinges on the interaction between an identified case of study and the context in which the case operates (Jones et al.). Therefore, below, I describe the context in which I gathered data.

Setting

I conducted research at UNG, a five-campus regional university with roughly 20,000 students and roughly 1,000 instructional personnel. In a given semester, around a quarter of the total student population takes a FYC course. English 1102 is the class from which I gathered data. This course is the second course in the compulsory two-step composition sequence. The semester I taught this class, the baseball team, from which my three research participants came, was in the middle of a historically successful season. They compiled a 46-12 record. They won their conference, and, for the first time in school history, played in the NCAA Division II Baseball Championship. The team filled up the record book with individual and collective team accolades. These details about the school, the athletics department, and the baseball team shape and reshape the research process in which we—researcher and participants alike—engage.

Research Participants

I first approached the faculty athletics representative (FAR) about offering a FYC class for student-athletes.{1} The FAR approved and pitched my idea to the athletics director who also approved. The FAR recommended—did not require—my class to the student-athletes she advised. Student-athletes are one population at UNG who receive priority registration, and by the end of priority registration, the class was full and included twenty-five student-athletes and one dual-enrolled student.{2}

According to Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations published under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), researchers should “minimize the possibility of coercion” (§46.116). Coercion can arise when a researcher researches their own students. The Conference on College Composition and Communication Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Research in Composition Studies, which, for full disclosure, I helped revise, cautions that

If the topic of the research or other special circumstances require that the study involve our own students, then we use measures to avoid coercion or perceived coercion, such as confirming students’ voluntary participation after grades are submitted or asking colleagues to conduct the actual data collection.

It’s hard to minimize coercion when engaging with power dynamics that come with a teacher researching their own student. I attempted to minimize coercion by waiting until I posted final grades to reach out to student-athletes to see if they would participate in my research project. In consultation with the FAR, I emailed five student-athletes who completed English 1102 about participating in this IRB-approved study. We selected these students based on their in-class participation and perceived availability (many students-athletes, like many students, work outside jobs and balance a full class load). One student-athlete wrote and declined; another did not respond. The three who positively responded were all baseball players:

- Andres Perez{3}: a sophomore business management major who plays catcher on the baseball team.

- William Mapes: a sophomore business management major who plays shortstop on the baseball team.

-

Bill LeRoy: a sophomore math education major who plays catcher on the baseball team.

At the time I taught the class, all three student-athletes were second-semester first-year students. When I collected data, all three were first-semester sophomores.

Data Collection

In my office, I audio-recorded then transcribed the semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with the student-athletes. I analyzed two papers they authored during our class, looking for moments where their talk about MSK made its way into alphabetic text in their paper or where their alphabetic text articulated MSK in ways their talk did not. I then asked the student-athletes to replicate a literacy mapping exercise we did in class. Mapping exercises serve learners as helpful metacognitive frames because they allow learners to visualize (and verbalize) their thoughts (Pintrich). Mapping exercises also serve researchers who study writing development (Prior and Shipka). In line with asking the student-athletes to visualize and verbalizing their thinking, I asked the three research participants, and all the students in the class, to engage in a physical representation exercise. I opened with this bodily exercise and return to it again. Taken together, the three research participants engaged with metacognition through speaking, writing, drawing, and feeling. I emailed the final draft of this essay to the three participants. None responded.

Literature Review

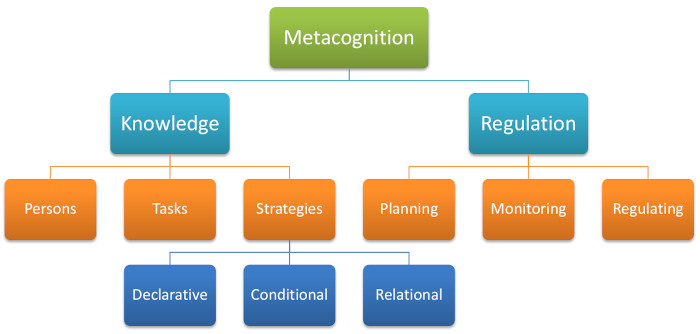

Researchers still use psychologist John Flavell’s 1979 work on metacognition in which he defines metacognition as “knowledge and cognition about cognitive phenomena” (906). He separates “phenomena” into four different classes: metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, goals, and actions (906). Following Flavell’s work, psychologists often divide metacognition into a knowledge component and a regulation component. I think of this delineation as one between knowing about metacognitive skills and using metacognitive skills. As I show in figure 1, knowledge is further broken into three categories: knowledge of persons, knowledge of tasks, knowledge of strategies. The final category (knowledge of strategies) is broken into declarative, conditional, and relational strategies. Moving back to the top of the taxonomy in Figure 1, with knowledge as one component and regulation as another, educational psychologists divide regulation into three kinds of procedural knowledge: planning, monitoring, and regulating. This before, during, and after aspect of procedural knowledge lines up with a common three-step approach to the writing process within educational psychology: preaction, action, and post-action.

Figure 1. Education psychologists organize the dynamics of metacognition.

During the past two decades, educational psychologists investigated metacognition’s role in developing academic writing skills by offering a taxonomy of metacognition founded on Flavell’s work because, as educational psychologists Douglas Hacker et al. argue, “writing is applied metacognition” (154). Researchers show that metacognitive abilities separate strong and weak academic writers (Perin et al.), and researchers offer longitudinal studies on the development of metacognitive skills of basic writers at a community college (Negretti), high school students (Karlen et al.), and children (Harris et al.).

More closely connected to the work I offer here, Icy Lee and Pauline Mak and Raffaella Negretti and Lisa McGrath focus on metacognitive scaffolds in the writing classroom. I borrow the term metacognitive scaffolds from Roger Azevedo and Allyson Fiona Hadwin who describe metacognitive scaffolds as instructional devices such as writing assignments, activities, and tools that “enable students to develop understanding beyond their immediate grasp” (16). These scaffolds provide learners with effective footholds in learning new material. Lee and Mak offer two examples of metacognitive scaffolds for L2 writers: a writing regulatory checklist and writing logs. The writing regulatory checklist, as a specific metacognitive scaffold, offers multiple reflection questions for writers to consider. These questions are broken into three sections: before writing, during writing, and after writing. Returning to figure 1, which offers an organizational hierarchy of aspects of metacognition, the three sections of Lee and Mak’s writing regulatory log align with the three aspects of procedural knowledge (preaction, action, and postaction). Ultimately, they argue that these metacognitive scaffolds help student-writers become “self-regulated and independent writers” (1095), a key goal for writing development as seen in professional documents such as the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing and the WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition (v. 3.0).

Negretti and McGrath also turn attention to metacognitive scaffolds as pedagogic interventions for strengthening students’ writing development. Turning attention to L2 doctoral researchers in a writing course, Negretti and McGrath attend to how “promoting metacognitive knowledge can enhance different facets of genre knowledge” (14). They invite their research participants to engage with two metacognitive scaffolds: a written task, in which participants were asked to activate prior genre knowledge, and a visualization and reflection scaffold in which participants created a visual conceptualization of the genres in their discipline and a written reflection on how these insights may be of use in future writing contexts. Following these two metacogntive scaffolds, Negretti and McGrath conducted interviews with the student and found that these two metacognitive scaffolds “seemed quite successful in pushing students to integrate and verbalize various facets of their genre knowledge” (28). Negretti and McGrath’s findings connects with the Outcomes Statement, which details the importance of faculty helping students learn the main features of genres in their fields of study.

Such pedagogically focused work on metacognition illustrates how instructors can leverage metacognitive scaffolds in varied academy settings. I add onto this research by working with a student population that has a great deal of experience with structured metacognitive prompts and assignments outside of the traditional academic classroom and ask how student-athletes draw on their prior knowledge and practice of non-academic metacognition in FYC. Additionally, I add to this research by offering what instructors may learn about metacognition from listening to student-athletes and how student-athletes deploy it in extracurricular spaces. To focus my analysis of metacognition, I employ Karlen’s offering of metacognitive skills knowledge (MSK).

Metacognitive Strategy Knowledge

Karlen offers MSK as an integral skill of strong academic writers. He draws on John Borkowski and Lisa Turner’s conceptualization of a metamemory model and Gregory Schraw and Rayne Sperling Dennison’s work on metacognitive awareness. Karlen defines MSK as “verbalizable knowledge about disadvantages and advantages of specific strategies regarding task characteristics” (63). MSK includes conditional strategy knowledge and relational strategy knowledge. Remembering the organizational hierarchy in figure 1, conditional and relational are two types of procedural knowledge nested under knowledge. Relational strategy knowledge covers “processes that refer to the awareness of differences and similarities between strategies” (63) and conditional strategy knowledge is “knowledge about when and why specific strategies are useful” (63). According to Karlen, “MSK enables writers to critically consider a specific writing task, determine what strategies will be best to achieve the goals for that specific task, and identify why and when which strategy should be applied for successful task fulfillment” (63).

In this article, I take up MSK for two reasons. First, I see a strong emphasis on rhetorical situation. While Karlen does not highlight this emphasis, I argue that both relational and conditional strategy knowledges are bound up in rhetorical concerns: audience, purpose, genre, kairos. For one, conditional strategy knowledge is “knowledge about when and why specific strategies are useful” (63; emphasis added). This nod to kairos, purpose, and constraints calls to mind Keith Grant-Davie’s work on the rhetorical situation and Kathleen Blake Yancey et al.’s emphasis on writing across contexts in their work on writing transfer, a cognitive phenomenon facilitated by metacognition.

Second, I turn to MSK because it creates space for student writers to claim agency over their writing development. Karlen views MSK as an “important link between individuals’ self-regulation of the writing process and writing achievement” (63), a point he carries to his work with psychologist Miriam Compagnoni. Karlen and Compagnoni argue that “the more academic writing is seen [by students] as an ability that can be learned and taught at university, the higher the students’ MSK” (53; emphasis added). As a writing teacher, my eyes leap at Karlen and Compagnoni’s phrase “can be learned and taught” because it positions academic writing as a skill people can hone, not an esoteric art reserved for the worthy few. When learners approach writing from this beneficial position, they are more likely to have higher MSK. Through metacognitive scaffolds that facilitate the development of MSK, writers can develop self-regulation and, thus, develop their writing skills.

My semi-structured interviews with Perez, Mapes, and LeRoy highlight their verbalizable knowledge about MSK. My reading of their essays highlights their practice of MSK. These two data points (interviews and artifacts) help me better understand the student-athletes’ knowledge and practice of MSK. Karlen’s quantitative research design provides a rich data set for thinking about writers. My qualitative research design adds student voice to these quantitative data. Though I am only reporting on the writing performance and development of three students and though I am only highlighting two specific assignments these students completed, I firmly believe that the data I offer is an important complement to the rise in U.S. higher education of what Marc Scott terms “big data analytics” (56). U.S. higher education is turning into a data-driven business with mounds of student data guiding retention and one-semester persistence initiatives. I’m grateful for big data analytics. I’m grateful for national surveys coming out of the Center for Postsecondary Research at Indiana University, the Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA, and the U.S. Department of Education. I’m grateful for colleagues like David West Brown and Laura Aull who pull from large data corpus to sketch a picture of student writing. But I want us to remember our students and their unique voices and experiences and desires and hopes when we scan over data points. As a researcher, I am committed to bringing student voices into conversations about teaching and learning. As writing program administrator, I am committed to hearing from our students as a counterbalance to the mounds of institutional effectiveness data that lands on my desk tidily packaged into Excel spreadsheets. While I only report on three student-athletes, their voices and others like them have much to teach us—writing instructors, administrators, and researchers—about writing development, about the experiences and joys and struggles of writing, and about how we might design and redesign our writing-intensive spaces for those students with whom we labor.

Student-Athletes’ MSK in Two First-Year Composition Assignments

I designed the 16-week FYC course around five writing assignments and used Elizabeth Wardle and Doug Downs’s textbook Writing about Writing (WAW), which helped students develop rhetorical awareness. I also sought to help students develop rhetorical practice; therefore, I implemented key terms borrowed from Yancey et al.’s Teaching for Transfer (TFT) curriculum. Students and I worked with eight of the recommended twelve key terms recommended by Yancey et al.: genre, audience, exigence, rhetorical situations, reflection, context, discourse community, and knowledge. I capped the key terms at eight because these eight terms were most clearly reflected in readings from WAW. I also borrowed one assignment from Yancey et al.’s TFT curriculum: a theory of writing grounded in these key terms. In sum, I pulled from two similar pedagogical approaches to composition instruction (WAW pedagogy and TFT pedagogy) both of which offer structured moments of reflective writing in which student engage. These moments helped students hone MSK.

Rhetorical Analysis of a Previous Writing Experience: Strengthening Conditional Strategy Knowledge

In the first writing assignment from which I report, students performed a rhetorical analysis of a previous writing experience based on an assignment in WAW. The rhetorical analysis assignment helped hone students’ conditional strategy knowledge. Wardle and Downs ask students to explore two broad questions at the close of their essay: “What did you learn from this? What principles might you draw to help you in future writing situations” (479). These questions connect with conditional strategy knowledge.

I included three activities to support students’ work on this assignment. First, I invited students to use Grant-Davie’s Rhetorical Situations and Their Constituents (included in WAW) as a lens for viewing how their rhetorical situation shaped a previous writing experience. Second, students and I worked through four of the eight key terms from the TFT curriculum (audience, genre, rhetorical situation, and exigence). Third, we spent time on a basketball court to visualize the importance of our key terms. In the physical activity that opens this essay, a student needs to take the basketball from one baseline to other (94 feet) without running with the ball or dribbling the ball. To move this distance, the student needs to pass and receive the ball from classmates scattered around the court. These classmates represented different aspects of writing and rhetoric (including our key terms) with a sign on the floor signifying what they represented. One student represented exigence, another audience, another genre. One student represented the rhetorical situation and the fifth student represented sources. The student going from baseline to baseline represented the writer and the journey from baseline to baseline was the writing process. To move from one end to the other, to move from invention to circulation, a writer needs help, needs to engage with audience, genre, and exigence. A writer needs sources, needs to understand their rhetorical situation. Instead of reading these concepts, I aimed to give the students an opportunity to feel these concepts, to visualize these concepts, to use these concepts physically.

In his essay, Room for Improvement: A Student’s Awakening to Writing in College, William Mapes draws attention to a text he wrote in English 1101, the first course in UNG’s FYC sequence. All quotes come from his writing. The text, which he refers to as a “research paper,” focused on the War on Terror. He wrote it “in the library one night ... with coffee by my side ... and [listening] to some country music.” According to Mapes, the strategy he most heavily relied on was surface-level editing. In the second paragraph of his text, he explains why he relied on this strategy:

In order to please my audience, [the instructor], I made it a priority to closely follow the rubric. When talking to one of my older teammates about my teachers, I was informed that [the instructor] was a stickler when it comes to grading. This led to me trying to precisely follow the instructions of the paper. I did not use the word ‘I’ or use contractions. I also made it a priority to make sure I maintained the same tense throughout the paper instead of being inconsistent with my use of tense.

Mapes does acknowledge the importance of developing a strong argument and organizing around this argument: “It was very important to have a good thesis statement and to make sure the entirety of my paper related back to my thesis.” He mentions “thesis statement” only twice: once to tell readers that he included a “strong thesis statement” in his War on Terror research paper; once to tell readers the importance of having a “good thesis statement” for his instructor. Mapes’s body paragraphs cover how he sought grammatical correctness because, in his words, “[the instructor] was not grading based on my argument.” In his final paragraph, Mapes stresses the importance of “reviewing past performances” and writes that his “goal is to continue to eliminate wordy sentences and fluff within my paper.” Because of his audience, or maybe more accurately, because of his perception of his audience, Mapes focused energy on surface-level issues and put surface-level issues at the top of his priority list for future writing assignments.

Perez writes about the same instructor and assignment as Mapes. Again, all quotes come from Perez’s writing. In “A Look Back Into Writing: Reviewing a Previous Essay and the Process of Writing It,” Perez introduces us to his English 1101 research paper on steroid use in professional baseball. Like Mapes, Perez thinks hard about how the audience shaped his strategies:

Because my audience was [his instructor], I was careful not to base my research solely on my opinion but instead reach further to provide evidence for both arguments well enough that [the instructor] has sufficient information to form [their] own opinion ... I provided statistics from before and after their [former players Barry Bonds’s and Roger Clemens’s] alleged use to show how much steroids can improve a player’s performance. I also provided evidence from those who played, coached, and watched the game from either press boxes or stands because everyone has a different perspective and opinion.

Though Perez and Mapes were in the same class, during the same semester, even though Perez and Mapes had the same instructor and sat next to each other in the library writing an assignment to the same prompt and same rubric, the two deployed different strategies to accomplish their task. Perez focused on argument, bringing in perspective from a variety of baseball stakeholders. He did not want to state a clear opinion on the issue; instead, he sought to provide enough balanced information to allow the instructor to form their “own opinion.” Perez does not fret over surface-level correction like Mapes. Near the end of his text, Perez does mention that his instructor did not like his use of “words like ‘some,’ ‘all,’ or ‘most.’” But Perez emphasizes presenting appropriate evidence instead of eliminating contractions. Both writers display conditional strategy knowledge and discuss why they focused energy on specific aspects of the writing process. Though they reach difference conclusions, both display a knowledge about why and when. Such an ability meets with the Outcomes Statement, which nests this rhetorical ability under “Processes,” one of four outcomes FYC courses attempt to distill in student-writers.

The rhetorical analysis paper introduced students to thinking about when to use specific writing strategies and tailoring these strategies to the contextual nature in which writing occurs. The three activities I used to support students’ writing development and to support their work on this assignment helped them establish connections between the literacy practices of baseball and academic writing, which, in turn, bolstered their development of MSK awareness. As LeRoy told me during our interview,

The basketball example in the court ... and like some of that kinda made sense. I just remember, each person had to rely on someone else to score the basket. It kinda clicked. It showed that writing a paper is not something you do by yourself. And I was always the guy that just kinda sits down there not really looking for sources, just writing out thoughts, blah, blah, blah. But you have help; you have sources; you have people here. And it shows, you know, you are not alone when you are writing.

After these words, I remember LeRoy pausing. I felt he was done and reached to turn off my digital recorder when he offered his final comment while tugging on his hat: “And after writing some of the papers, I realized, you know, the scouting report, a lot of the things did relate to baseball. We need writing, we need communication, a lot of that is key and relates to baseball.”

The three student-athlete writers drew from their prior experiences with metacognition, added to these prior experiences by engaging with conditional strategy knowledge, and, through this addition, further developed MSK awareness. But MSK also calls upon learners to understand the differences and similarities between strategies; MSK also calls upon relational strategy knowledge. Therefore, the second paper comprising this data set invited students to draw connections between two discourse communities and consider the composing practices inherent in both.

Discourse Community Analysis: Strengthening Relational Strategy Knowledge

During our interviews, the baseball players described how their team prepares for games with the aid of collaboratively compiled charts based on past performance data. The college baseball season is broken into series with teams competing against each other in three-game series played over three consecutive days. The first game is often on a Friday night; the final game on a Sunday afternoon. Perez explained their preparation: “most conference weekends, we will sit down on Thursday after practice. It will be a short meeting—what they like to do as a team, if they are scrappy or rely on the homerun, like whatever.” The team also holds smaller meetings. Mapes explained the pitching coach leads a meeting for the pitchers; the head coach and hitting coach lead a meeting for the hitters. Mapes attends the hitter meetings and told me that coaches provide a scouting report with “every pitcher, speed for every pitch, every pitch they throw, their tendencies.” This report helps players “kinda get to know what kind of pitcher he is before you face him, so you can kinda get an idea of what he is planning.” Additionally, the report tells players about a pitcher’s common pitches, tendencies of what the pitcher throws and when, and a pitcher’s average speed. LeRoy attends the hitter meetings with Mapes. LeRoy said, the “scouting report is printed out and pinned up in the dugout right beside our helmet. When a new guy [pitcher] comes in, we check to see what number he is and look at him on this chart ... it gives us a head’s up for what to look for.” Aggregating information on an opponent’s past performance, a form of audience analysis, helps a player’s future performance. As LeRoy told me, “I look over everything he [the coach] gives us and base my plan of attack or approach on each guy and then mentally prepare myself. So, if I get down in the count—no balls and two strikes—what is he going to throw, what are his tendencies? So just thinking about what I am going to do if I am ahead in the count or behind in the count.”

Pitchers also analyze the opponent to better future performance. Perez, though a catcher, attends the pitcher meetings. He told me, “we will talk a lot with our pitching coach. He will get with me about certain tendencies and ways to throw to a hitter. And the pitcher will know that going in [to the game]. So, we will try to exploit that weakness [of the hitter] and pitch around their strengths.” The coaches discover these weaknesses through analyzing spray charts compiled by their players. Spray charts visualize the location of every ball a player hits in-play. These data help defenses prepare for hitters. “We keep two charts,” Perez said, “one is for our team, the other is to see where the other team hits it ... If they pull the ball a lot, we will try to throw them outside because you can’t really pull an outside pitch. The players record the data. They have a chart and just write down where the ball goes.” At the end of a Friday night game, Perez said, the coaches sit down with these newly tallied spray charts and adjust for the second game in the series. Though college sports demand a high-level of physical preparation, metacognition features prominently in how the team prepares for the many three game series constituting a forty-game college baseball season. The discourse community analysis essay I assigned built onto student-athletes’ prior experiences with broad applications of metacognition. Perez, Mapes, and LeRoy developed a stronger awareness of metacognition through practicing relational strategy knowledge in this assignment.

For this essay, I drafted an assignment that invited students to draw connections between their literate practices used in a college writing class and their literate practices used in an extracurricular space. To help students think about literate connections, I introduced three more key terms taken from the TFT curriculum (discourse community, context, and knowledge) and evident in many of the readings in WAW.

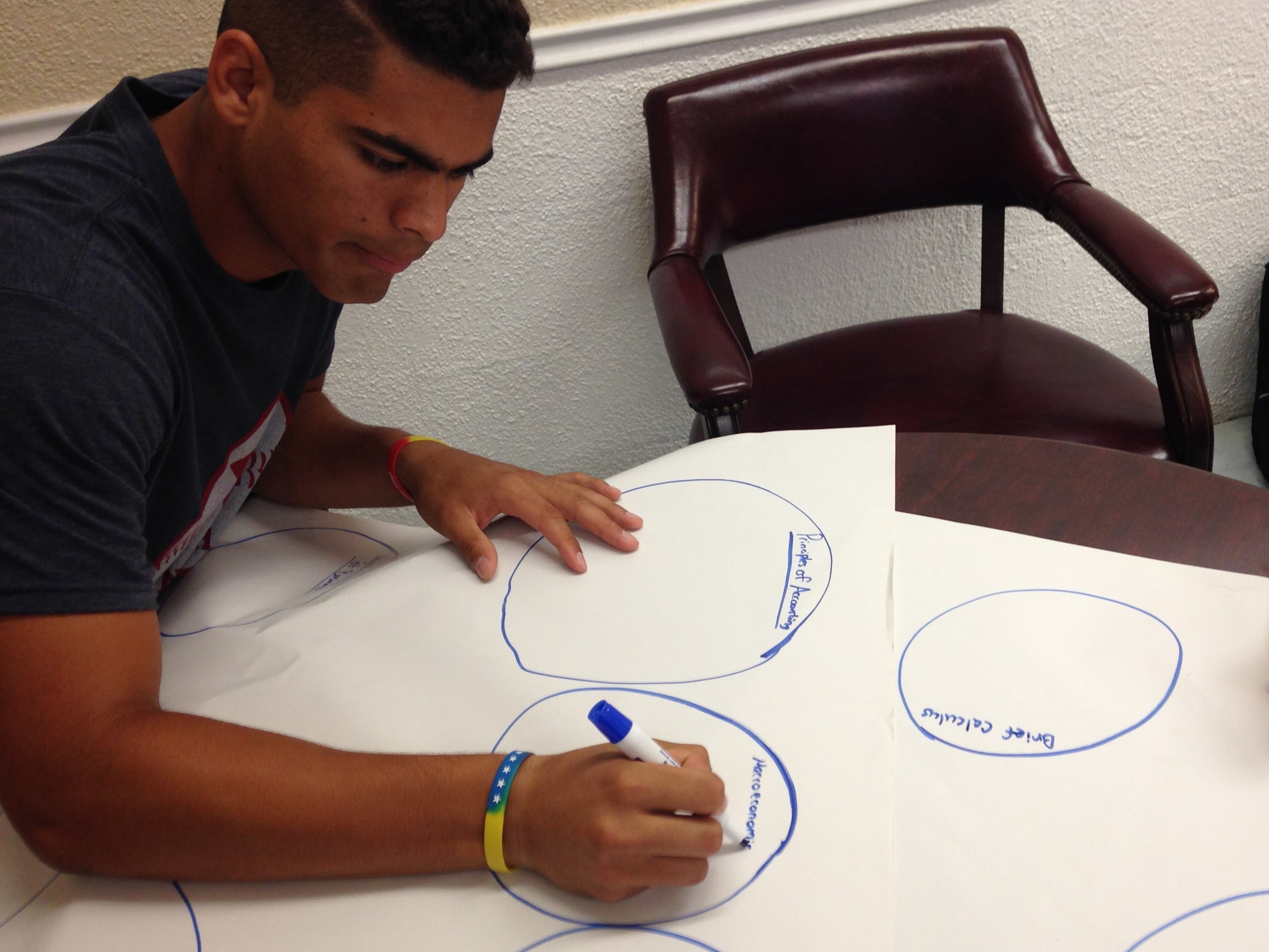

Students and I also worked through a visual mapping exercise. We visualized our school and non-school discourse communities on poster paper with dry erase markers. Students drew a large circle for each class in which they were enrolled, wrote the name of the class in the circle, and then connected each circle with a solid line. I then asked them to draw a square for a non-school discourse community in which they are a part. Again, the students labeled this square. Some scribbled down religious groups on their paper, some Greek affiliations, student clubs. Many scribbled down their athletic team. I asked students to then draw a dashed line between their square and a circle (an academic class) most closely connected to their square in terms of literate practices. In the figure below, Perez works on his map.

Figure 2. Andres Perez maps his literate practices.

In Relation of Writing and Athletics: Non-School Literate Practices, Bill LeRoy opens with a sentiment surely shared by many of the student-athletes in the class: “Baseball is a discourse community in which you would not expect many literate practices from or a relation between it and writing.” Despite the rocky syntax, LeRoy takes his opening and turns it on its head: “However,” he writes, “in baseball there are many cases in which reading and writing is necessary or extremely beneficial.” For the next four paragraphs, LeRoy connects the literate practices of baseball with those espoused in a FYC class. He describes baseball scouting reports and spray charts; he invites readers to read the thoughts swirling through his head when batting: “how many outs are there? Are there runners on base? Or where has the pitcher tried to throw the ball in previous at bats?”

The excerpt below comes from LeRoy’s paragraph on the scouting reports and spray charts. He establishes a connection between gathering this kind of information for baseball and undertaking research for an academic paper. I quote LeRoy in full to allow his voice to come through:

Baseball has a literary [sic] practice that deals more with writing specifically with the creating and interpreting of scouting reports and spray charts. A scouting report is an observation of the opposing pitcher on what pitches he has, how hard he throws, and a description of something obvious that he may do to give hitters an edge of advantage over him. A spray chart is a visual representation of where hitters have hit the ball in previous at bats for pitchers to see their tendencies to have an edge over them. Both scouting reports and spray charts take time and effort to create being that you have to watch film of every pitcher and hitter over and over to get an accurate description of them. The same time and effort has to be put into obtaining background information for a paper. The same way coaches and players watch film, authors must research their topic in books and on the internet to get a full understanding of it and to have an edge over the material that he or she may be writing about. Being that this concept of baseball actually involves reading and writing has helped me translate more direct benefits to my writing and comprehension skills.

In his penultimate paragraph, LeRoy describes disconnects between the literate practices of baseball and academic writing, “especially when it comes to word choice and communication.” LeRoy admits to using “made up” words and “terrible” word choice in baseball. He doesn’t provide examples but later writes of his “repetitive use of adjectives and questionable word choice” on the field. He worries “simple word choice translates to my writing and typically has an effect on how powerful my papers could be.”

Mapes picks up the TFT language when he authored the title of his paper. I stylize the title as it appears: “Transferring communities: From non-school writing to school writing.” Mapes, unlike LeRoy, starts his essay by grounding it in class reading. He draws from Lucille McCarthy’s longitudinal study of an undergraduate student named Dave. McCarthy’s article is included in WAW and illustrates how Dave struggles to understand how writing in one academic context is different than writing in another academic context. Mapes spends two paragraphs detailing struggles Dave experienced as he moved through difference class, different discourse communities. In his fourth paragraph, Mapes brings his focus to the heart of the essay:

Despite having a completely different discourse community and writing style [than Dave], the personal writing I do for baseball helps in my school writing ... In order to become a better baseball player every day, I keep a personal journal recording every detail of all of my at-bats throughout the course of a game. My exigence for the journals is to progress as a baseball player by learning something new every day. I can do this by learning from the mistakes I make and reviewing them, so I am more prepared for when the situation arises again. When I record my journals, I am not concerned with length or proper punctuation since it is for me to keep. Instead, I focus on getting my main points across in the clearest way possible. I use short bulleted lines, abbreviations, and dashes to effectively write in the form that works for me. Because I am not concerned with critiquing small details, I am able to focus on being clear and concise and I can avoid adding unnecessary information in my journal. I translate this to my school writing because I can have the same plan of being clear and concise in articulating my main point to the reader while being aware of potential grammar errors in my writing.

Through responding to this discourse community assignment, LeRoy and Mapes articulate how they enact similar and different cognitive processes to accomplish a baseball task and an academic writing task. The student-athletes offered verbal explanations of how metacognition operates in baseball by describing how pitchers and hitters need to review spray charts and other data points prior to performance. The discourse community assignment served as a metacognitive scaffold to help the student-athletes see the importance of gathering data in academic writing. LeRoy thinks broadly about the cognitive preparation necessary for baseball. He draws connections between baseball and academic writing by approaching scouting reports and spray charts as living documents that players and coaches actively use for task completion (i.e., winning a baseball game). As LeRoy writes, “The same time and effort has to be put into obtaining background information for a paper.” Relational strategy knowledge speaks to processes, speaks to concrete actions undertaken by a learner. LeRoy thinks about processes involved in baseball and processes involved in academic writing—both require “background information” and “time and effort.” But the two are different. He writes that on a baseball field, his “word choice and communication” is “terrible” because of “repetitive adjectives and simple word choice.” He does not provide examples, but he understands a key difference in processes between baseball and academic writing and can put these different processes into action.

Mapes, like LeRoy, looks to background preparation as a connecting process between baseball and academic writing. Mapes keeps a “personal journal recording every detail of all of my at-bats throughout the course of a game.” This action prepares him for future at-bats. But it is not the journal itself that piques Mapes’s interest; he’s interested in the writing style he uses when detailing his past experiences. He seeks to write “clear and concise” details and “avoid adding unnecessary information in my journal.” When I initially read Mapes’s paper, I expected him to argue academic writing also often demands “clear and concise” prose. Instead, he falls back on the auxiliary verb can and writes a speculative sentence: “I translate this to my school writing because I can have the same plan of being clear and concise in articulating my main point to the reader.” The can halts the effectiveness of the sentence, moving the sentence from a declarative statement to a fuzzy possibility. I may be putting too much emphasis on a three-letter verb tucked into a sentence in the middle of a paragraph and in the middle of the paper. But Mapes wrote about “adding unnecessary information” and “being clear and concise.” Here’s a place in Mapes’s thinking where he could push more, where, as the instructor, I could invite him to think deeper about how relational strategy knowledge figures into baseball and academic writing. He understands one physical process he undertakes to complete a task in baseball: using a specific writing style in his personal journal. But he struggles to articulate clearly how these processes either figure or not into academic writing. He hedges a potentially powerful sentence with a deflated can—not a declarative does.

The rhetorical analysis paper asked students to flex their conditional strategy knowledge muscles; the discourse community paper asked students to flex their relational strategy knowledge muscles. The three baseball players flexed these muscles in our writing class but built these cognitive muscles through their sport.

Conclusion

Sports are embodied literate practices requiring participants to engage in metacognitive activities to improve future performance. As rhetoric and composition scholars turn greater attention to the importance of structured metacognitive scaffolds in FYC curricula, I suggest we can benefit by working with and learning from student-athletes. Designing assignments that ask student-athletes to hone MSK, then, offers reciprocal benefits to instructors and student-athletes.

Instructors learn the importance of community and collaboration in metacognition when working with student-athlete writers. The basketball team I researched for a year only watched film collectively or in small groups; film sessions were not individual exercises. Players shared responses aloud as coaches guided discussion. The baseball players in this study also describe the collaborative spirit of film sessions. The team gathers to prepare for their opponent. The pitchers hold a preparatory meeting with the pitching coach; the hitters hold a preparatory meeting with the hitting coach. Communally-compiled and communally-used spray charts and scouting reports line the walls of the team’s dugout. Though Mapes keeps a personal journal that includes “detail of all of my at-bats throughout the course of a game,” the metacognitive activities are communal; players and coaches coming together with data from previous games in hopes of improving in future games.

In this spirit, I ask how metacognitive scaffolds—from high-stakes writing assignments to low-stakes class activities—might draw from this knowledge of metacognition in athletic spaces to take on a more communal and collaborative nature. Biologist Kimberly Tanner’s work on metacognition in science classrooms includes helpful tables of reflective prompts. But many of these prompts carry first-person pronouns: “What insights am I having as I experienced this class session? Do I find this interesting? To what extent did I successfully accomplish the goals of this task?” (115; emphasis added). I wonder: how might we support a writer’s development if instructors adjusted Tanner’s questions to include a we instead of the individual I? Borrowing from the baseball players in this study who described team meetings are separated into different skill positions, one method would invite instructors to assign metacognitive prompts after students turn in a paper. The instructor would place students in groups according to different parts of the paper: an introduction group; a conclusion group; two groups on body paragraphs. Each group would collectively work through two prompts grounded in relational strategy knowledge and conditional strategy knowledge (i.e., the two components of MSK). They would modify the content in brackets for whatever group they are in:

-

What did you need to understand about this assignment and your audience to write [this portion of your paper]? (conditional strategy knowledge)

-

What challenges came with writing this [portion of your paper] that did not come with writing other portions of your paper? (relational strategy knowledge)

These questions, like Tanner’s questions, are first-person pronoun focused. But the groups would work together, drawing from their various paragraphs to think collectively. Groups would then share aloud their findings to the class, pointing to sections of their classmates’ writing to bolster their argument. Such an activity lends a communal spirit to a generally individual and quiet activity of reflecting on one’s own thinking.

Student-athletes also benefit from what we know about metacognition in the writing classroom. As instructors, our role is to bring the language of metacognition and the many terms that fall under this large umbrella term into class. We should talk explicitly about processes and strategies and tasks and the kinds of knowledge and practices needed for these processes and strategies and tasks. We should build a curriculum, utilizing assignments and activities like those described in this article, that offers moments of individual and collective reflection through metacognitive scaffolds. The work I outlined here shows that connecting metacognition to students’ prior experiences and weaving these metacognitive scaffolds into two common rhetoric and composition assignments facilitates connections between prior athletic experience and academic writing situations for student-athletes. Through working with our student-athletes and pressing into scholarship on metacognition from across disciplines, we can provide a pedagogical moment, a space, where students and instructors mutually develop a greater understanding of the importance of thinking-about-thinking.

Finally, to be fair, the words the student-athletes wrote for these assignments and the words they provided during our interviews can, partially, be a byproduct of their experience with metacognition for baseball. Actually, I hope this is the case. Our students enter our writing-intensive spaces with a wealth of prior writing knowledge and experiences. Through structured assignments and activities and clear and measurable objectives, we can support those experiences by adding to them, complicating them, and qualifying them. When I began conceptualizing this class and later when I began conceptualizing this essay, I knew I would meet a point where it would be unclear what actually helped student-athletes develop as writers. Would students do well with these assignments, and, in turn, develop as writers because they already were familiar with metacognition through their sport? Or would they do well with these assignments and, in turn, develop as writers because of these assignments? What was the chief contributor to their writing development? My data show that the activities and assignments delineated out as a conditional strategy knowledge assignment and a relational strategy assignment focused student-athletes attention to specific elements of metacognition that were not present in how they understood metacognition for their sport. As LeRoy said, “After writing some of the papers, I realized, you know, the scouting report, a lot of the things did relate to baseball.” LeRoy exhibits an understanding of relational strategy knowledge by drawing connections between strategies for academic writing and baseball.

Student-athletes engage with the broad application of metacognition through which they collect and analyze data on past performance to improve future performance. But they do not bring a nuanced vocabulary of metacognition into film sessions, and they use metacognition, not as the end goal, but to get to the end goal of winning a game. For the assignments I detail, the focus itself was metacognition, specifically to display an understanding and application of conditional strategy knowledge and relational strategy knowledge. Sure, the ultimate goal for the writers was a strong grade on the paper. But these assignments asked writers to remain focused on teasing apart elements of metacognition, establishing connections, seeking out points of difference and similarities between strategies. I purposefully built onto student-athletes’ established prior knowledge and practices in hopes of pushing them to new knowledge and new practices. Through these assignments and through the TFT key terms, through the embodied activities, through the mapping exercises, through the four pages of intense focus on MSK, these three student-athletes moved beyond the broad application of metacognition honed through their sport to a more acute understanding of metacognition—metacognitive strategy knowledge.

Notes

-

A faculty athletics representative is an NCAA required position wherein the FAR, as a full-time faculty member, acts as a liaison between athletics and academics. (Return to text.)

-

A dual-enrolled student is a high school student who is taking a college class. At the time of this draft, UNG counted 1,400 dual-enrolled students. (Return to text.)

-

With permission, I used all students’ real names. I first gained this permission from the student-athletes. I then gained this permission from the athletics department. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Azevedo, Roger, and Allyson Fiona Hadwin. Scaffolding Self-Regulation Learning and Metacognition: Implications for the Design of Computer-Based Scaffolds. Instructional Science, vol. 33, no. 5, 2005, pp. 367-79.

Borkowski, John G, and Lisa A. Turner. Transsituational Characteristics of Metacognition. Interactions Among Aptitudes, Strategies, and Knowledge in Cognitive Performance, edited by Wolfgang Schneider and Franz E. Weinert, Springer-Verlag, 1990, pp. 159-76.

Brown, David West, and Laura L. Aull. Elaborated Specificity versus Emphatic Generality: A Corpus-Based Comparison of Higher- and Lower-scoring Advanced Placement Exams in English. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 51, no. 4, 2017, pp. 394-417.

CCCC Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Research in Composition Studies. Conference on College Composition and Communication. 2015. http://www.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/ethicalconduct.

Cheville, Julie. Minding the Body: What Student-Athletes Know About Learning. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2001.

Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and National Writing Project. Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing. 2011. http://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf.

Council of Writing Program Administrators. WPA Outcomes Statement (v3.0). 2014. http://www.wpacouncil.org/positions/outcomes.html.

Flavell, John H. Metacognition and Cognitive Monitoring: A New Area of Cognitive-Developmental Inquiry. American Psychologist, vol. 34, no. 10, 1979, pp. 906-11.

Grant-Davie, Keith. Rhetorical Situations and Their Constituents. Writing about Writing, 2nd ed., edited by Elizabeth Wardle and Doug Downs, Bedford, 2014, pp. 347-65.

Hacker, Douglas J., et al. Writing is Applied Metacognition. Handbook of Metacognition in Education, edited by Douglas J. Hacker, et al., Routledge, 2009, pp. 154-72.

Harris, Karen R., et al. Metacognition and Children’s Writing. Handbook of Metacognition in Education, edited by Douglas J. Hacker, et al., Routledge, 2009, pp. 131-54.

Jones, Susan, et al. Negotiating the Complexities of Qualitative Research in Higher Education. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2014.

Karlen, Yves. The Development of a New Instrument to Assess Metacognitive Strategy Knowledge about Academic Writing and Its Relation to Self-Regulated Writing and Writing Performance. Journal of Writing Research, vol. 9, no. 1, 2017, pp. 61-86.

Karlen, Yves, and Miriam Compagnoni. Implicit Theory of Writing Ability: Relationship to Metacognitive Strategy Knowledge and Strategy Use in Academic Writing. Psychology, Learning & Teaching, vol. 16, no. 1, 2017, pp. 47-63.

Karlen, Yves, et al. The Effect of Individual Differences in the Development of Metacognitive Strategy Knowledge. Instructional Science, vol. 42, no. 5, 2014, pp. 777-94.

Lee, Icy, and Pauline Mak. Metacognition and Metacognitive Instruction in Second Language Writing Classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1085-1097.

McCarthy, Lucille. Stranger in Strange Lands: A College Student Writing Across the Curriculum. Writing about Writing, 2nd ed., edited by Elizabeth Wardle and Doug Downs, Bedford, 2014, pp. 230-62.

Negretti, Raffaella. Metacognition in Student Academic Writing A Longitudinal Study of Metacognitive Awareness and Its Relation to Task Perception, Self-Regulation, and Evaluation of Performance. Written Communication, vol. 29, no. 2, 2012, pp. 142-79.

Negretti, Raffaella, and Lisa McGrath. Scaffolding Genre Knowledge and Metacognition: Insights from an L2 Doctoral Research Writing Course. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 40, 2018, pp. 12-31.

Rifenburg, J. Michael. Writing as Embodied, College Football Plays as Embodied: Extracurricular Multimodal Composing. Composition Forum, vol. 29, Spring 2014. http://compositionforum.com/issue/29/writing-as-embodied.php.

Rifenburg, J. Michael. The Embodied Playbook: Writing Practices of Student-Athletes. Utah State UP, 2018.

Perin, Dolores, et al. The Academic Writing of Community College Remedial Students: Texts and Learner Variables. Higher Education, vol. 45, no. 1, 2003, pp. 19-42.

Pintrich, Paul R. The Role of Goal Orientation in Self-Regulated Learning. Handbook of Self- Regulation, edited by Monique Boekaerts, et al., Academic Press, 2000, pp. 451-502.

Prior, Paul, and Jody Shipka. Chronotopic Lamination: Tracing the Contours of Literate Activity. Writing Selves / Writing Societies: Research from Activity Perspectives, edited by Charles Bazerman and David R. Russell, WAC Clearinghouse, 2003, pp. 180-238, https://wac.colostate.edu/books/selves_societies/prior/prior.pdf.

Schraw, Gregory, and Rayne Sperling Dennison. Assessing Metacognitive Awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, vol. 19, no. 4, 1994, pp. 460-75.

Scott, Marc. Big Data and Writing Program Retention Assessment: What We Need to Know. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Programs, edited by Todd Ruecker, et al., Utah State UP, 2017, pp. 56-74.

Tanner, Kimberly. Promoting Student Metacognition. CBE-Life Science Education, vol. 11, 2012, pp. 113-20.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45: Public Welfare. 2009. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/ohrp/policy/ohrpregulations.pdf.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and Doug Downs, editors. Writing about Writing: A College Reader. 2nd ed. Bedford, 2014.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, et al. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State UP, 2014.

Student-Athletes from Composition Forum 43 (Spring 2020)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/43/student-athletes.php

© Copyright 2020 J. Michael Rifenburg.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 43 table of contents.