Composition Forum 41, Spring 2019

http://compositionforum.com/issue/41/

Extending the “Warming Trend” to Writing Transfer Research: Investigating Transformative Experiences with Writing Concepts

Abstract: In this article, we investigate a new construct for conceptualizing learning transfer with writing knowledge: Transformative Experience (TE). With origins in educational psychology, TE has been effective for promoting transfer with scientific concepts in previous research, but not yet considered in relation to writing or other presumably procedural subjects. To investigate the usefulness of TE for revealing new dimensions of writer development, we present a brief case study focused on faculty members writing for scholarly publication. We use qualitative responses to a survey about faculty members’ experiences in a formal writing group to illustrate the three dimensions of TE in the context of writer development: active use, expansion of perception, and experiential value. Although we study advanced faculty writers, findings have implications for teaching and learning writing more broadly. Specifically, we argue that using TE as a framework for interpreting what learners do with writing knowledge widens the “warming trend” in transfer research, nuancing our understanding of writing transfer by attending to perceptual and experiential aspects of learning. We propose instructional interventions to test how incorporating TE into writing pedagogy might enhance teaching and learning for transfer.

The issue of knowledge transfer is a vital concern for writing teachers and writing studies scholars, and a growing body of research addresses teaching and learning writing for transfer (Beaufort; Wardle, Understanding; Yancey et al.; Eodice et al.; Wardle, Writing and Transfer; Driscoll and Powell; Driscoll and Wells). Nevertheless, given the unique complexity of writing knowledge and the “ill-structured” contexts that call for its application (integration, adaptation, repurposing, etc.), determining how writers learn and transfer their learning remains difficult to do (Snead; Wardle, What Is Transfer? 144). In this article, we address this challenge by reporting results from an interdisciplinary collaboration among the authors—a researcher from educational psychology and a researcher from writing studies. More specifically, we explore the potential of TE, a construct from educational psychology, to shed new light on the processes through which learners develop and transfer writing-related knowledge. We argue that TE reveals meaningful aspects of learning that can be obscured by traditional notions of writing transfer that privilege dramatic transformation and don’t always integrate cognitive, behavioral and affective dimensions of learning. As a more integrative framework, TE may bring to light how small, straightforward acts of transfer accumulate and eventually pave the way for more dramatic transfer events.

TE usefully complicates theories of transfer that underscore dramatic transformation in how learners see subject matter, themselves and the world. This type of transformation is central to threshold theory, which has significantly informed conceptualizations of writing transfer (Adler-Kassner et al.; Moore, Five Essential Principles; Moore, Mapping the Questions; Moore and Anson). Adler-Kassner and Wardle spearheaded the move to identify and operationalize writing studies threshold concepts—foundational knowledge about writing that is transformative, integrative, and irreversible (Naming What We Know; Naming What We Know: The Project of this Book 2). Threshold concepts have become an important “framework for designing for and understanding transfer of writing knowledge across contexts” (Adler-Kassner et al.; Moore and Anson 6). Notably, threshold theory is associated with transformative learning (TL), a particular type of learning that involves dramatic change in perspective and worldview (Mezirow). From a TL perspective, internalizing threshold concepts entails ontological and epistemological shifts in perception that impact how a learner sees the world. Learning is painful, or “troublesome” because it necessarily challenges prior knowledge; learning involves wallowing in liminal spaces before crossing irreversible conceptual thresholds or gateways (Land et al.; Perkins; Timmermans). However, as Heddy and Pugh point out, transformative learning can be difficult to achieve, observe and maintain over time. In contrast, TE is a “‘micro’ form of transformative learning” that doesn’t necessarily cause dramatic change in identity or worldview but does “facilitate[e] a change in perception” of a concept or idea in relation to the learner’s life and experience (Heddy and Pugh 53). In this way, TE offers “a framework for conceptualizing a little t transformative learning approach” as distinct from Mezirow’s capital T transformative learning (Heddy and Pugh 52). Capital T transformative learning is difficult for instructors to facilitate in a short period. The TE framework allows instructors to make smaller, more pedagogically manageable, transfer events more meaningful. After practicing small t transfer, students may be more prepared to engage in capital T transformation.

In addition to nuancing views of writing transfer based on the dramatic transformation of learners’ worldviews, TE explicitly integrates cognitive, behavioral and affective dimensions of learning. Despite efforts, particularly in writing studies, to investigate how students’ identities and dispositions inform transfer (see for example Bromely et al.; Driscoll and Powell; Driscoll and Wells; Wardle, Creative Repurposing), transfer is still largely viewed as a “cold” construct, meaning that transfer is presumed to happen without the influence of other cognitive, motivational, and affective influences. Gale Sinatra argues that researchers would benefit from exploring a “warmer” version of cognitive constructs such as transfer by studying affective and motivational characteristics. That is, although scholars tend to describe conceptual change (the process of moving from inaccurate to accurate knowledge frameworks) in a purely behavioral or cognitive manner, conceptual change is a complex process that includes more affective components such as engagement, emotion and personal relevance. Thus, investigating transfer without also measuring related constructs such as interest, value and emotion only allows for comprehending a small portion of the process of transfer. A focus on TE extends the warming trend in writing transfer research by reiterating that transfer is not only a behavioral and/or cognitive process. Students’ experiences of their learning and how they value its impact on their lives and perceptions are vital components of successful transfer; TE integrates this experiential component with the other components to construct a more robust notion of transfer.

Despite the potential of TE to enrichen our understanding of writing transfer, TE has not yet been tested with writing or other subjects perceived to be more procedural than conceptual. TE was developed to support science learning in K-12 contexts and has been effective for promoting transfer with psychology concepts in previous research (Heddy et al.). Because outside the discipline of writing studies writing is not perceived to involve conceptual learning, however, educational psychology researchers have not considered investigating the relevance of TE in the context of writing development. Yet, as collections such as Naming What We Know attest, writing involves procedural and conceptual knowledge that is relevant for all writers and calls for complex learning processes. Therefore, we argue TE is a relevant construct for facilitating conceptual learning in the context of writing development and for understanding a wider range of transfer activities. In what follows, we theorize TE in the context of writing development and offer a brief case study to illustrate how writers experience TE. In doing so, we reveal different pathways to writing transfer and highlight implications for writing teachers and researchers.

Transformative Experience (TE) in Writing: Multidimensional Engagement with Content

Transformative experience can be conceptualized as engagement with content that occurs outside of the initial learning experience (Pugh, Transformative Experience). TE occurs when learners transfer knowledge learned in one context to a different context and recognize the value of the content for its ability to influence their lives (Pugh, Transformative Experience). More specifically, TE has three components that capture various types of engagement with content: 1) active use, 2) expansion of perception and 3) experiential value (Heddy and Pugh). Active use occurs when learners notice content learned in one context in a new context. For example, a writer may learn about the concept of writing as a social process while in a writing group. When they are writing with a team of researchers using Google Docs they may think about the concept of writing as a collaborative process. When noticing the concept while writing, active use has occurred. The active use component of TE is closest to what Perkins and Salomon call near- or low-road transfer, the direct use or application of a concept learned in one context in a closely related context (Teaching for Transfer; Transfer of Learning; Salomon and Perkins).

The second component of TE, expansion of perception, goes beyond behavior-based transfer by attending to how learning impacts learners’ perceptions of the subject matter and the world around them. For example, thinking about writing as a social process while writing may change the way a writer perceives writing. The writer may have originally viewed writing as a solo endeavor and due to learning about how writing can be collaborative, they now see writing differently. In a similar vein, the third component of TE goes beyond behavior and cognitive forms of transfer to consider how learners value their learning. Experiential value occurs when a writer realizes that writing collaboratively can positively influence their writing ability. When the writer has experienced each of the three components, the writer has engaged in transformative experience with the concept of writing as a social process.

Considerable overlap is possible among the three components of TE. For example, if a learner thinks about the concept of writing as a social process while writing collaboratively using Google Docs and realizes how the concept changed their approach to writing, then active use and expansion of perception have co-occurred. The fact that components of TE can happen simultaneously is in line with research suggesting that TE occurs on a continuum (Pugh, Transformative Experience). The low end of the continuum is when a learner thinks about how concepts can impact everyday experiences while sitting in class; the high end involves actual experiences with content in one’s everyday life, including recognition of all three components of TE. Therefore, transformation can take place as a small change where learners actively use content outside of the learning context (lower end of the continuum) or as a larger transformation where learners engage in all three components of TE (high end of the continuum). At the high end of the continuum all three components co-occur to create a holistic transformative experience.

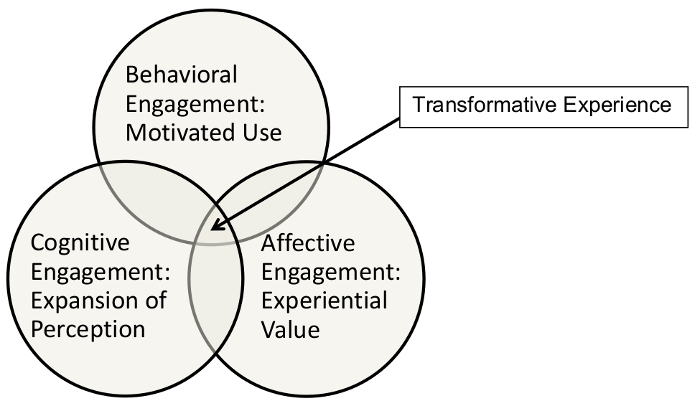

The three components of TE overlap with the three dimensions of engagement as conceptualized by researchers (Fredricks et al.): behavioral, cognitive and affective (see figure 1). Behavioral engagement occurs when learners physically engage while learning, for example raising their hands or nodding when listening to an instructor. Active use is related to behavioral engagement because learners are physically looking for concepts outside of the initial learning environment. Cognitive engagement is operationalized as learners mentally wrestle with ideas or make connections between concepts. Expansion of perception overlaps with cognitive engagement because re-seeing an experience in terms of the newly learned concepts is a cognitive and perceptual activity. Finally, affective engagement occurs when learners are emotionally involved with their learning, when they are interested in the content or frustrated with having incorrect ideas, for example. Experiential value is similar to affective engagement because value is composed of interest and enjoyment based on the concepts enriching one’s experience. Because TE lives at the intersection of these dimensions of engagement, it can lead to optimal learning and motivation.

Figure 1. The relationship between the three dimensions of engagement and the three components of TE.

Much research has been conducted on the benefits to learners of engaging in transformative experiences (Alongi et al.; Heddy and Sinatra, Transforming Misconceptions; Heddy et al.; Pugh et al., Motivation; Pugh et al., Teaching for Transformative Experiences). Research has shown that engaging in TE can generate positive affect (Heddy and Sinatra, Transforming Misconceptions), facilitate and develop interest (Alongi et al.; Heddy et al.) and contribute to conceptual change and achievement (Pugh et al., Motivation). Research on TE has been conducted mostly in science (Heddy and Sinatra, Transforming Misconceptions; Pugh et al., Motivation) but has also ventured into psychology (Heddy et al.) and social studies (Alongi et al.). Until now, to our knowledge no research has been conducted on TE in writing.

The dearth of research conducted on TE in writing may be due to the common perception that writing is a procedural field. TE research focuses on applying concepts to everyday experience in such a way that one's experience is enriched by a personally relevant connection. Beyond the field of writing studies, writing is not perceived as subject laden with concepts but as a process or procedure. It could be argued that engaging in a procedure in a new context is transfer but not TE because perception is not changed by the dynamic interaction of a concept and the environment. However, we contend that this logic is flawed on two grounds. First, describing writing as not conceptual in nature is inaccurate as evidenced by recent work on writing studies threshold concepts (Adler-Kassner and Wardle, Naming What We Know). The popular and enduring curriculum movement Writing about Writing (Downs and Wardle; Wardle and Downs, Reflecting Back; Writing about Writing) is based on the recognition that the field of writing studies has both declarative and procedural knowledge about writing that can and should be conveyed directly to students. Learning about the nature and workings of the activity of writing empowers students to act from their knowledge instead of having writing done to them (Wardle and Downs, Reflecting Back). Because writing is a field with declarative, conceptual knowledge, it makes sense that a construct such as TE, designed to study and facilitate conceptual learning, could be a valuable framework for teaching and learning writing.

Furthermore, TE is relevant in the context of writing even if we focus on writing as a procedural activity as research suggests an integral relationship between procedures and concepts. Anderson explains that understanding the conceptual mechanisms of a procedure is integral to learning that procedure. That is, procedural knowledge (knowledge of how to do things) is made up of declarative knowledge (knowledge of concepts and ideas). Wardle and Downs (Reflecting Back) explain this relationship in the context of writing. Teaching a student to write a memoir (procedural learning) will likely not lead to learning transfer unless the student is faced with writing a memoir again in the future. However, if in teaching the student to write a memoir the teacher introduces the writing concept of “situatedness”—the idea that “good” writing is defined differently according to rhetorical situation—then the student learns how to make decisions while writing her memoir based on a particular rhetorical situation and learns how to examine new rhetorical situations in order to respond to unfamiliar writing tasks in the future. The point here is that even though writing has a significant procedural component, procedures are closely related to conceptual knowledge. Thus, TE should be possible with procedural writing knowledge.

Why Study TE in Writing?

Studying TE in writing is not only appropriate but, we argue, a useful endeavor for several reasons. First, TE can help writers recognize the immediate impact of writing-related learning. Learners do not always make connections between writing concepts learned in one context and writing experiences in other contexts because writing tasks are so complex and varied, what Wardle calls “ill structured” rhetorical problems (What Is Transfer? 144). As a result, students are rarely required to directly apply skills and strategies learned in writing classrooms (i.e. writing a memoir) in the wide-ranging contexts in which they write across and beyond the university. More likely, they are required to perform what Perkins and Salomon call far transfer or high-road transfer by remixing, repurposing, and/or integrating prior knowledge to address significantly different writing tasks (Teaching for Transfer; Transfer of Learning; Salomon and Perkins). That complex process is often difficult to achieve and to detect. However, the lens of TE highlights how students transfer concepts from a learning context to an everyday experience, such as a writing session (low-road transfer) and how active use of the concept relates to changes in how students perceive and value their experiences. Therefore, TE has the potential to crystalize the impact of learning about writing by connecting the application of writing concepts to motivation and personal relevance with writing.

Investigating TE in writing can also usefully complicate the perceived practical nature of writing. Many learners perceive writing not as a subject with its own conceptual knowledge domain but rather as a set of practical skills. In fact, many people outside the field of writing studies would be hard pressed to describe concepts that exist in writing, despite efforts by writing studies scholars to reveal the conceptual foundation of writing and articulate writing-related threshold concepts at the heart of the field (Adler-Kassner and Wardle, Naming What We Know). Identifying TE with writing may help reinforce what Wardle and Adler-Kassner call the “meta” threshold concept of writing—that writing is an activity (procedure) as well as a subject of study (a body of conceptual knowledge). As we will show, the TE framework has the potential to reveal concepts that are relevant for learners, concepts that may not be thresholds to capital T transformation, but nevertheless may shift learners’ perceptions of writing and/or of themselves as writers and enhance how they value their writing experiences. Wardle and Downs urge writing teachers to use “any means necessary and productive, in order to shift students’ conceptions of writing, building declarative and procedural knowledge of writing with an eye toward transfer” (Reflecting Back). By determining which writing concepts learners use and how their perceptions and experiences change as a result, TE may provide a new way to heed that call.

Finally, understanding the phenomenon of TE with writing concepts may help generate interest, motivation and learning with writing. Writing researchers know that motivation is key for learning transfer; we also know that motivation can be tricky when it comes to writing transfer because of common misconceptions about writing, students’ learned dispositions about writing, and because writing courses don’t always provide motivation for students to transfer what they learn (Bergmann and Zepernick; Driscoll and Wells; Wardle, Understanding). Research shows that facilitating TE can generate student interest (Heddy and Sinatra, Transformative Parents; Heddy et al.), motivation (Pugh et al., Motivation), and achievement (Heddy and Sinatra, Transforming Misconceptions; Pugh, Newton’s Laws; Teaching for Transformative Experiences). Thus, investigating TE with writing concepts is a promising first step toward determining if teaching for TE can facilitate learning and motivation for writers as has been the case in previous research on learners in different domains including science (Pugh et al., Motivation), history (Alongi et al.), and psychology (Heddy et al.).

An Illustrative Case Study

To get an initial look at TE in the context of writing, we studied writers in the midst of critical transitions that called for new writing practices and identities: early career faculty members working on scholarly publications who chose to participate in a facilitated writing group. Although writing transfer research tends to focus on undergraduate student learning and school-to-workplace transitions, we chose to focus on faculty writers for several reasons. First, because we embrace “a long view on writing development” that assumes all writers change as they encounter and address new writing situations across the lifespan (Bazerman et al.), faculty writers are an appropriate focus for research on how writers learn. Second, scholarship argues for the transformative potential of faculty development (Cranton, Professional Development; Understanding and Promoting; Cranton and King), making faculty writing groups, a focused form of professional development, a promising site for studying transformative experiences. Although results of our investigation are certainly relevant for faculty support efforts, our primary purpose is to show that TE is possible in the context of writing and to begin to explore the value of the TE construct as a lens for understanding what writers learn about writing and what they do with what they learn. Therefore, our findings are relevant for writing teachers and researchers working with undergraduate students, and we detail specific implications and applications in the discussion section below.

To investigate the potential of TE in the context of writing development, we examined how faculty members in a writing group demonstrated the three components of TE. More specifically, we asked: 1) do faculty writers report using concepts that they learned about writing in the group when writing within their daily experiences? 2) do faculty writers perceive writing differently as a result of their participation in the writing group? and 3) do faculty writers value the concepts from the writing group for their ability to impact their writing experiences?

Participants and Context

Faculty participants were recruited from three different writing groups organized around Wendy Laura Belcher’s Writing Your Journal Article in Twelve Weeks: A Guide to Academic Publishing Success. The writing groups, facilitated by a leader who participated as a writer to varying degrees, met regularly over the course of a semester, loosely structuring their meetings according to the chapters in Belcher’s book. Each group member worked on an article-length project, engaging with chapters such as Advancing Your Argument, Reviewing Related Literature, and Giving, Getting, and Using Others’ Feedback. Participants included twenty-two faculty from two universities. Sixteen participants were from a large university in the Mid-South with Carnegie’s “highest research” designation; ten participated in a 2016 writing group and six in a 2017 writing group. Six faculty members participated in a writing group in spring 2017 at a large university in the South with Carnegie’s “higher research” designation.

Participants represented a range of disciplines, including architecture, education, modern languages, social work and land systems science among others. The majority were from social science disciplines (12), eight from arts and humanities, one from science and engineering, and one associated with both social science and arts and humanities. Participants identified as White/Caucasian (15), Black (3), African American (1), German American (1), and Latina/Puerto Rican (1). One person chose not to identify. Only two participants were men.

Survey

Participants were surveyed immediately following their writing group experience with an instrument adapted from Kathleen P. King’s Learning Activities Survey (LAS) based on Jack Mezirow’s stages of perspective transformation{1}. Closed and multiple selection survey questions were designed to identify “the presence and possible triggers of transformative learning” (King 28) faculty experienced during the writing group. This brief case study focuses on responses to three open-ended survey questions that were added to detect TE, each question designed to capture one of the three components of TE (active use, expansion of perception, experiential value). Prompts were modeled after survey questions used to detect TE in science (Heddy and Sinatra, Transformative Parents; Pugh et al., Teaching for Transformative Experiences) (See Appendix).

Components of TE in Faculty Writers’ Responses

To explore the presence of TE in the participants’ open-ended responses, two independent readers studied each participant’s series of responses noting instances in which the faculty member demonstrated active use (reported using a writing-related concept outside the writing group), expansion of perception (described a change in perception about writing or self as writer), and/or experiential value (indicated a shift in how they valued the experience of writing). In what follows, we offer examples of the components as manifested in faculty writers’ survey responses. All three components were observed. In the excerpts below, numbers in brackets indicate which survey question the section of response addressed. Underlined sections indicate aspects of the response that demonstrate the TE component being discussed. As we mentioned, components of TE sometimes overlap. In our study, a participant’s response to one survey question might indicate no components, one component, two components or all three components of TE. When we highlight particular components in the examples below, we are not suggesting that the excerpt illustrates one component instead of another. We are simply demonstrating that a given component existed in the participant’s response.

Active Use: Writing Concepts in New Contexts

Active use is similar to the traditional “cold” operationalization of transfer as a behavioral process of searching for or noticing writing concepts and ideas in a new context. Writers in our study demonstrated active use when they were inspired by discussion in writing group to experiment with different writing spaces or realized they could accomplish some writing tasks in short bursts, contrary to previous assumptions that writing required long blocks of time.

Kate: [1] I’ve never been able to write in my workplace office, partly because I have always had to share office space, so the space never really feels like “my space” or is not quiet enough, or is too close to others. I have begun trying to reimagine office space on campus as a place to write—particularly at certain times of the day—and to imagine what I can do to create a space that is more conducive not only to writing, but to writing regularly and more habitually. [2] I still think that, for me, much [of] the actual WRITING part of academic writing needs to be done in considerably longer blocks of time than it does for others. I have seen that I can revise and annotate already existing drafts of writing in shorter blocks of time. That said, it does take some time for me to get into the groove of writing—especially if that writing involves initial drafting of a piece of writing—and it is [in] that groove that I feel best about writing and feel that I write well. I found that I could actually work on something (not necessarily write anything new) surrounded by other writers all focused on purportedly doing the same thing. This has made me want to seek out another writing group and/or a dedicated writing space in the future.

The series of responses from Kate indicates active use. In response to the first prompt, she describes her effort to think about the “when” and “where” of writing. Participating in the writing group urged her to think about her assumptions related to the ideal writing space. Kate put new ideas about writing time and place to use by actively creating a space conducive for habitual writing. Moreover, she internalized the idea, introduced in writing group, of writing in short bursts of time. Although Kate acknowledged that generating text still requires long sessions of concentrated effort, she explained how she successfully applied the “shorter blocks” concept when revising and annotating existing drafts. Finally, after realizing her ability to write alongside fellow writers, Kate professed a plan to continue to seek out writing groups and/or dedicated writing space in the future. These moves constitute active use because Kate recalled ideas introduced in writing group, reflected on those ideas, and changed her practices and habits based on the ideas. She provided significant detail about the ideas and her change in practice.

Active use is essentially low-road transfer, transfer of knowledge between similar contexts. It is possible that Kate changed where and how long she wrote when it was convenient to do so and might not continue the practice when her schedule is not as conducive. Like the student Eugene in Robertson et al.’s study, Kate may be demonstrating “assemblage” by “breaking [her] new learning into bits, atomistically, and grafting those isolated ‘bits’ of learning onto [her] prior [understanding of writing] without either recognition of differences between prior and current writing conceptions and tasks, or synthesis of them.” After all, she does maintain the belief that she needs certain conditions to do certain types of writing. At the same time, she acknowledges that she has the power to “reimagine” where and how she writes and that sense of empowerment over her writing life is rooted in her ability to enact, even temporarily, new practices. Practicing the new behavior solidified its potential and made it more likely that Kate will look for future opportunities to enact the behavior when possible. Of course, active use is only one component of TE. Considering active use alongside the other two components, expansion of perception and experiential value, helps nuance our understanding of writing-related transfer by surfacing the connection between seemingly insignificant instances of low-road transfer and more substantial forms of learning that sustain learner motivation and make high-road transfer and Transformative Learning more likely.

Expansion of Perception: New Understandings of Writing and Self as Writer

With expansion of perception we begin to see a “warmer” version of transfer, as learners take the next step beyond using a construct in a new context, which is where traditional transfer research often ends. In our case study, expansion of perception was evident when faculty described how they thought of some aspect of writing differently as a result of their participation in writing group. Billie’s responses, in particular, show a significant shift in her writerly self-perception.

Billie: [1] I catch myself starting to berate myself for not accomplishing a writing goal I set, and I interrupt the negative self-talk. I do my best to shift my energy from berating myself to regrouping from wherever I am and moving ahead. This is something we talked about in writing group in discussions about staying motivated and getting the writing done. [2] Learning about writing in writing group helped me understand that people who get published aren’t necessarily smarter or more disciplined than I am. Surely some of them are, but not everyone who is getting published is a brain giant. There’s nothing magical about getting academic writing done (though I do hold out hope that parts of the process feel magical). [3] Much of my writing process work involves getting out of my own way. The ideas above help me to do that more effectively.

Billie’s responses demonstrate expansion of perception because in her first response, she described in detail how she was able to “catch” herself engaged in negative self-talk, to “shift [her] energy” toward “regrouping…and moving ahead.” She attributed the change in perception directly to discussions in the writing group about motivation and productivity. Moreover, Billie’s second response describes a second perspectival shift, this time in how she thought of herself in relation to other writers. Again, she attributed her new sense of herself as just as capable of publication as other writers to “learning about writing in writing group.” Her response suggests that Billie no longer sees academic writing as a “magical” feat but as a matter of sustained motivation and persistence. Finally, Billie’s third response explicitly acknowledges that writing, for her, entails “getting out of her own way.” The self-realization constitutes a change in perception, one Billie acted on by embracing the shifts described in her first two responses.

Learning about the writing concepts in the faculty writing group changed Billie’s perception of her approach to her own writing process. The TE framework reveals how faculty like Billie experienced their writing in exciting new ways and how those experiences expanded their perceptions of writing and of themselves as writers. Making the connection between use and perception could help writing teachers recognize and support writing behaviors that trigger more positive emotions and productive motivation (Heddy et al.).

Experiential Value: Impact of Learning on Experience

Working alongside the behavioral (active use) and the cognitive (expansion of perception) components, experiential value represents the affective dimension of TE and allows for an even “warmer” investigation of the transfer of writing constructs. Traditionally transfer research ends with the application of the writing ideas or practices in a new context. However, experiential value adds a motivational and affective component to transfer. Interestingly, we observed less detail in faculty responses associated with experiential value than in responses associated with active use and expansion of perception, which suggests the need for increased attention to this component. The following responses from Janine illustrate experiential value; her learning in the writing group helped mitigate negative dispositions toward writing, namely feelings of overwhelming pressure, guilt and dread.

Janine: [1] The writing group suggested not tearing yourself apart if you did not get the opportunity to write during your designated writing time. [2] I used to feel overwhelmed by writing and completing a manuscript in one semester but I realized that you cannot place pressure on yourself to perform. I learned to pace myself and not attach guilt to not meeting an expectation. [3] This experience reminded me that publishing is not just part of my profession but it falls in line with research that I value. Therefore, I can attach joy to the experience versus dread, guilt and resentment.

Here we see how Janine began to value the need to write and the experience of writing in new ways. Her responses include a description of all three components of TE, and thus represent a holistic transformative experience at the high end of the TE continuum. However, for the illustrative point of describing the third component of TE, we focus our analysis on experiential value. Janine named a suggestion from writing group (not tearing yourself apart) that she put to use; she also described a shift from feeling overwhelmed by the pressure to perform as a writer to learning to pace herself and squelch guilt about failed expectations. However, Janine went beyond use and change to demonstrate experiential value, as indicated in her final response. She articulated how her experience in the writing group reminded her of the internal motivation to publish, not (only) because she is required to, but because it allows her to disseminate research she cares about. Her recognition of the (internally defined) value of writing allowed her to associate joy with writing, rather than dread, guilt and resentment. When learners recognize the value of knowledge about writing for its ability to positively impact their experience, personal relevance and meaningfulness often occur. Given that writing can seem like a non-meaningful task, TE may be an effective method for generating connectedness to writing ideas in personally meaningful contexts.

Discussion: TE as a New Lens for Writing Transfer Research

Our small case study suggests the potential of TE as a framework for researching and teaching writing transfer and surfaces writing as a new context in which to study TE. Until now, TE researchers in educational psychology have focused on what they consider to be conceptual disciplines: science (Heddy and Sinatra, Transformative Parents; Pugh et al., Teaching for Transformative Experiences), social studies (Alongi et al.), and psychology (Heddy et al.). By showing that TE can happen in writing, our case study reinforces what writing studies researchers have long understood—that writing is conceptual as well as procedural—thus promoting, for the first time, writing as a viable focus for TE research. The call to continue to research TE in writing, a field that is different from those in which TE is typically studied, will ideally lead to new ways of theorizing and implementing the concept across contexts of teaching and learning.

Using the TE construct to examine how writers learn not only emphasizes for those outside the field of writing studies the conceptual nature of writing as an activity and a subject of study, but it also sheds new light on the relationship between practices and concepts. Kate’s change in practice in terms of the “when” and “where” of writing may seem like a practical behavior, low-row transfer, a far cry from engaging the more complex threshold concepts at the heart of writing studies as a discipline. However, a TE lens urges us to think differently about what counts as a “concept” in writing. Although the changes Kate made to her practice were not necessarily transformative in the sense of crossing a disciplinary threshold or shifting a worldview, they were meaningful in terms of how she thought of herself as a writer and how she valued the activity of writing. Unlike the slow, complicated transformations associated with threshold concepts that can be difficult to see and measure, the changes related to TE were immediate and recognizable (for the writers and for us as researchers). The simple (lowercase c) concepts Kate noticed—writing can happen in unexpected times and places and regular, short bursts of writing can move a project forward—and the recognizable changes in behavior they inspired might very well sustain Kate as she wrestles with more “troublesome” concepts, or wallows in “liminality” moving back and forth across learning thresholds, and struggling to transfer writing knowledge (Meyer and Land, Threshold Concepts).

Granted, writers in our case study are faculty members. However, the (lowercase c) concepts they embraced could be useful for undergraduate writers as well. For example, the concept of “slow scholarship” (Berg and Seeber; Hartman and Darab) came up during several writing group meetings and many writers mentioned it as an idea that helped validate the tension they felt between the desire for deep, immersive intellectual work and the pressure to produce writing for publication. The concept allowed them to name and claim a valuable approach to academic writing and research as well as explore creative strategies for achieving “slow” in the face of a publish or perish climate. Undergraduates, too, might appreciate discussion about the artificial nature of writing assignment due dates just as teachers might think innovatively about how to create flexible time in the writing classroom. Using TE as a lens for understanding what writers are learning, what they do with what they learn and how that learning impacts their self-perceptions as writers could enable teachers and researchers to identify a range of concepts that have not previously been considered in terms of transfer but could nevertheless powerfully impact developing writers and perhaps serve as pathways to more complex forms of transfer.

As mentioned previously transfer can occur on a continuum from low-road transfer, when content is applied in a context similar to the context in which it was originally learned, to high-road transfer, applying ideas in a context that is significantly different than the original setting (Perkins and Salomon Teaching for Transfer; Transfer of Learning; Salomon and Perkins). It could be argued that engaging in TE with writing ideas is a form of low-road transfer because faculty writers seemed to apply general strategies, such as working in short bursts, that didn’t require reconceptualization or repurposing. Researchers posit that low-road transfer is less meaningful and leads to lower levels of learning and deep level processing (Perkins and Salomon Transfer of Learning). However, we contend that engaging in TE could be a useful method for increasing the impactfulness of low-road transfer. We make this assertion because TE does not end with simple transfer but includes expanding perception and recognizing the value of concepts and procedures to enrich the writing experience. Thus, in the case of TE, low-road transfer becomes a meaningful, perception-altering experience that generates interest and enjoyment. Moreover, although transfer is currently viewed as a cold behavioral-cognitive activity, the TE framework foregrounds affect as an important piece of the transfer experience. Investigating the affective component of transfer allows for a more nuanced and meaningful understanding of writing transfer. By incorporating methods for generating affective engagement, such as interest, enjoyment, or pride, teachers can make low-road transfer more effective.

Whereas high-road transfer is difficult to achieve and facilitate, and is likely a rare occurrence (Salomon and Perkins), low-road transfer of simple concepts is easier to observe and support. Facilitating low-road transfer via TE is useful because it invites learners to practice transferring writing ideas to new contexts. Research shows that when learners practice transfer, they get better at the activity (Heddy et al.). Therefore, practicing low-road transfer will improve the likelihood that learners will be able to engage in high-road transfer because they will have practice with the learning strategy of transferring ideas between contexts.

Future Directions for TE and Writing

Based on our initial investigation of TE in the context of writing, we offer the following suggestions for teachers and researchers interested in pursuing the work we’ve begun.

Consider TE as a heuristic for supporting writer development.

Our observations are potentially useful for writing teachers and consultants supporting writers in various contexts. Most faculty in our investigation demonstrated TE, even though writing group facilitators did not consciously teach for TE. The knowledge that faculty writing group members are likely having transformative experiences—using concepts from writing group in their everyday writing lives, expanding their perceptions of writing and themselves as writers, and finding new value in the experience of writing—might inspire writing across the curriculum directors, faculty developers and writing teachers to more consciously design pedagogical activities that support these experiences.

Research in the field of educational psychology confirms that TE can be supported through instruction and significantly improved with targeted interventions (Girod et al.; Heddy and Pugh; Heddy and Sinatra, Transforming Misconceptions; Pugh, Teaching for Transformative Experiences; Pugh et al. Motivation). The Teaching for Transformative Experience in Science (TTES) model has been shown to effectively generate learning and motivation for students in science (Heddy and Sinatra, Transforming Misconceptions; Pugh, Teaching for Transformative Experiences; Pugh, Newton’s Laws; Pugh et al., Motivation), college success (Heddy et al.), and social studies courses (Alongi et al.). The model involves “evoking anticipation” by framing learning as an opportunity to use ideas to see the world differently; providing support or scaffolding for students as they “re-see” everyday experiences through content; and modeling personal experiences of “liv[ing] the content” (Heddy and Pugh 55). These strategies—priming, scaffolding, and modeling/reflection—probably sound familiar to writing consultants/teachers working with writers at all levels. Thus, adjusting and implementing them with an eye toward promoting TE constitutes a feasible, promising step for writing support professionals across contexts.

For example, in light of the writing studies threshold concept “reflection is critical for writers’ development,” described by Taczak in Naming What We Know, many writing teachers assign annotated writing portfolios and/or reflection essays in which students critically consider the choices they make in writing and explain how they operationalize what they have learned. The components of TE—use, change, and value—could be the foundation for a prompt or template guiding such reflections, drawing students’ and teachers’ attention to concepts used outside of classroom contexts, how those concepts shape learners’ perceptions of writing and writer identity and how learning about writing is uniquely valuable for individuals. Moreover, TE could support writing pedagogies like the one described by Downs and Robertson “that makes threshold concepts the declarative content of the course” (105). Such efforts, including what Yancey et al. call “teaching for transfer” models of writing instruction, focus on student conceptions of writing, asking them to develop and revise personal theories of writing during the course. Through personal theories of writing, students articulate “their conceptions of what happens when they write, what ought to be happening and why that does or does not happen” (Downs and Robertson 111). TE offers a straightforward framework for surfacing conceptions of writing and developing personal theories of writing by asking students to describe how they use writing concepts in their lives, how their perceptions of writing shift and how learning enhances experiential value. In short, as a heuristic for supporting writer development, TE provides a means of engaging with writing concepts that creates pathways to internalizing more complex threshold concepts even if students are not yet ready to embrace transformative shifts in their “values about writing that affor[d] a reconceptualization of writing” (Downs and Robertson 111).

Develop and test models of TE in writing.

Given that studies show that TE can be fostered through instructional techniques (Alongi et al.; Heddy and Sinatra, Transforming Misconceptions; Pugh et al., Motivation), researchers should systematically explore methods for facilitating TE with writing ideas. Research might include formal interventions to determine if/how TE in writing development improves when facilitators teach for transformative experiences. Researchers could adapt the TTES model to account for the dynamic relationship among procedural and conceptual knowledge in writing. For example, comparative interventions could be designed to consider similarities and differences in TE when writing skills as opposed to writing concepts are emphasized in writing development contexts. Given our observation that faculty writers were able to provide the most detail about the TE component active use, a Teaching for Transformative Experience in Writing (TTEW) model might focus more on promoting expansion of perception of writing as a practice and field of study and highlight experiential value of expanded perceptions.

Interventions could focus on the extent to which TE in writing is possible for more novice writers. Our focus on advanced academic writers raises questions such as: Were faculty more likely to demonstrate TE in a writing group because of their substantial experience with writing? Were faculty writers better able to articulate their active use, expanded perception, and experiential value because they have been writing for longer and in more sophisticated contexts? Researchers might study undergraduate and K-12 writers to determine if less advanced writers experience TE with or without formal intervention. Findings would deepen our understanding of writing transfer across the lifespan and surface implications for writing curriculum and pedagogy.

Finally, researchers should study TE as a tool for enacting culturally responsive teaching (Gay) or culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings)—writing instruction that embraces students’ cultural knowledge, prior experience and established worldviews as a foundation for teaching and learning. In particular, we see TE as a potentially useful framework for accomplishing two components among those Robert Rueda identifies as key for culturally relevant teaching: building comprehension of meaningfulness between in-school and out-of-school experiences, and teaching students to understand their own and their classmates cultures and experiences. When students apply content to their everyday life, as occurs in TE, they build meaningful bridges between home and school. Additionally, they discuss their TE with classmates, which may allow learners to understand their peers’ unique cultural experiences. In this way, teaching for TE may very well be a strategy for embracing Difference as a means of fostering writing-related transfer. Future research could elaborate the connection between TE and culturally relevant pedagogy in writing contexts.

Develop new ways to measure TE.

Researchers should experiment with best practices for measuring TE in writing. By observing that faculty writers demonstrated various components of TE in a writing group, our case study paves the way for researchers to more systematically identify and measure TE in writing. Currently, most studies in science education use the Transformative Experience Scale (Koskey et al.). Although this scale has been shown to be reliable and valid, it may not be as effective for writing content. Given the complex and personal nature of writing, assessing TE within the context of writing may be most accurately measured using a more qualitative approach such as the open-ended survey responses we used in our case study or think aloud protocols designed to capture participants’ TEs.

Moreover, researchers should develop means of observing and measuring TE over time. Transfer researchers and writing teachers know that the full effects of learning are often not immediately visible but tend to emerge over time when transfer is triggered in unpredictable ways. We also know that learning can be prominent in a learner’s mind and lose relevance or clarity over time. With this in mind, we plan to follow our case study participants, prompting them to reflect on how they use what they learned in writing group months and years after the writing group experience. Findings could reveal how TE relates to long term learning, lasting changes in perception, and/or sustained experiential value. We encourage researchers to explore multiple methods for assessing TE with writing concepts and practices.

Methods of capturing and measuring TE should take into account issues of Difference. In our case study, the only two faculty writers who did not demonstrate TE at all according to our definitions of the components were women scholars of color. Although we did identify strong examples of each TE component in the responses of other scholars of color, we are disturbed by this finding. As we mentioned, TE as a heuristic for stimulating learning theoretically aligns with initiatives such as CRP that seek to validate the cultural values and experiences of all learners. However almost no research has been done to investigate discrepancies in TE based on race, ethnicity or culture. Because the goal of our case study was to observe if writers experienced TE without a teaching intervention, we cannot speculate about the relevance of our finding for TE as a teaching heuristic. We do wonder, though, how our process of identifying and measuring TE could be more inclusive and attuned to cultural bias. In the field of writing studies, particularly in the area of writing assessment, researchers have made important strides in considering how difference, including race, culture and ethnicity, matters when it comes to understanding writer development (Inoue; Inoue and Poe; Poe Re-framing; Poe et al.). Future research should focus on designing TE interventions and measurement protocols that take seriously differences among learners as well as how “the white racial habitus” informs institutional discourses and research protocols related to writing development (Inoue 10).

Seek out interdisciplinary research collaborations.

A final implication of our research is the need for more interdisciplinary research studies among educational psychologists and writing composition researchers. These two fields have much to offer each other in terms of theoretical and conceptual understandings as well as methodological approaches. Although writing researchers draw on theories and concepts from the fields of educational and cognitive psychology (Driscoll and Powell; Driscoll and Wells; Fife) and some research has been conducted at the intersection of educational psychology and writing (Graham et al., Improving the Writing Performance; Graham et al., A Meta-Analysis), the extent of this research is limited. In this article, we’ve examined the usefulness of a construct from educational psychology, TE, for researching and facilitating learning about writing. Writing studies research has much to offer the field of educational psychology as well. For example, TE researchers had not previously considered TE in the context of writing because they perceived writing to be a practice and procedure rather than a field of study. However, recent scholarship that articulates writing studies threshold concepts highlights the conceptual body of knowledge at the heart of the field making TE a promising construct in this context. Threshold concepts in writing studies provide educational psychologists with a new area of research with regard to transfer, conceptual change and TE. TE researchers in educational psychology might now turn to other fields previously considered procedural in nature to explore the relevance of TE in those contexts as well. We hope our study serves as a catalyst to promote more cross-disciplinary research.

Conclusion

As Mya Poe pointed out in her 2014 review of Yancey et al.’s Writing Across Contexts, the first book-length study of transfer in writing, “the topic of transfer is undeniably one of the hottest topics in composition studies today” (145). Her observation remains true as writing researchers continue to investigate the complexities of teaching and learning for transfer and search for ways to make writing meaningful for all writers at all stages of development (Anson and Moore; Eodice et al.). A mere sample of recent scholarship shows researchers exploring writing transfer with multilingual students (DasBender); examining the role of dispositions and emotion (Driscoll and Powell), identity (Wardle and Clement), and threshold concepts (Adler-Kassner et al.) in learning transfer; and interrogating “co-construction of knowledge” (Winzenried et al.) as a transfer-related activity. Our study contributes to this growing body of research by examining for the first time the construct of TE from educational psychology in the context of writing development. More specifically, we extend the “warming trend” into writing transfer research by investigating transfer as a more integrated construct that includes behavior, cognition and affect with the goal of making writing a transformative experience.

In doing so, we respond to several aspects of Poe’s call for advancements in writing transfer research (Review). We integrate transfer-focused research traditions from more than one field, in this case writing studies and educational psychology, enhancing conversations about transfer in writing studies and paving the way for future interdisciplinary collaborations. We take a small step beyond “localism” by using tentative findings to explore possibilities for developing instruments for data collection and analysis that are more inclusive, attuned to cultural bias and relevant (if not generalizable) in a range of contexts. Finally, although we do not make claims about curricular change in relation to writing development, our findings shed light on writers’ experiences of learning in ways that might eventually lead to changes in writing pedagogy and curriculum with the goal of TE in mind. Writing is a uniquely complex activity. Writers across contexts and stages of development grapple with issues of engagement, motivation, persistence, interest, productivity, and achievement, as we are regularly faced with ill structured exigencies for writing that never look quite like those we’ve addressed in the past. Our study of TE in writing introduces a new construct for supporting writers and teachers of writing as we embrace these opportunities.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Anis Bawarshi, Mary Jo Reiff, Greg Giberson, Tom Sura and anonymous reviewers for their feedback on this manuscript. Special thanks to members of The Southwest Consortium for Innovative Psychology in Education who attended the 2017 SCIPIE conference for engaging with the research and ideas at the heart of this article. We are especially grateful to the faculty writers who so graciously shared their experiences and perspectives as research participants.

Appendix

The following survey protocol was piloted in 2016 and modified in spring 2017:

Please take a moment to reflect on how your experience in the writing group has impacted you{2}. Consider times when you applied specific ideas from writing group to your writing routine or process. Perhaps something you learned in writing group changed how you understand or approach academic writing. Do you value or experience writing differently as a result of your time in the group? Now please respond to the following questions:

[Active Use] Describe a time when you thought about or used ideas from writing group outside the designated meeting time. For example, a writer might explain that lately when she feels strapped for writing time she recalls writing group discussions about expanding the “when” and “where” of writing and feels motivated to write in unusual times and places.

[Expansion of Perception] Explain how learning about writing in writing group changed your perception of academic writing. For instance, the writer from the previous example might explain that she used to assume academic writing required long stretches of deep concentration apart from her daily routine. Now she sees how academic writing projects can be broken down into manageable tasks and worked into her busy schedule.

[Experiential Value] Based on your responses above, describe how the ideas you learned in writing group are valuable to you. For example, a writer might explain that because the writing group leader encouraged her to experiment with when and where she wrote, she’s reminded that she enjoys writing and is beginning to look forward to, rather than dread, the little time she is able to spend writing each day.

Notes

-

We acknowledge the impact of timing on responses. Faculty might eventually forget about ideas or practices they reported as valuable on the survey right after the workshop. Alternatively, over time faculty might come to see the value in ideas or practices from the workshop that they failed to identify in their initial survey responses. Our larger study follows faculty over several years in order to investigate TE over time, and we plan to publish longitudinal findings in the future. For now, initial survey responses offer snapshots of self-reported learning that give insight into the potential for TE in writing. (Return to text.)

-

Instead of asking “to what extent” faculty were impacted by their participation in writing group, we asked them to “describe how”: learning impacted their behavior, learning changed their perceptions, and learning was valuable to them. We did so to increase the likelihood that faculty would respond to the questions. Some survey responses did not indicate any component of TE, which suggests that the framing of the question did not prevent faculty from indicating the writing group had no impact on their behavior, perception or value. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda, et al. Assembling Knowledge: The Role of Threshold Concepts in Facilitating Transfer. Anson and Moore, pp. 17-47.

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth Wardle. Naming What We Know: The Project of This Book. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 1-11.

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth A. Wardle, editors. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State University Press, 2015.

Alongi, Marc D. et al. Teaching for Transformative Experiences in History: Experiencing Controversial History Ideas. Journal of Social Science Education, vol. 15, no. 2, 2016, pp. 26-41.

Anderson, John R. ACT: A simple theory of complex cognition. American Psychologist, vol. 51, no. 4, 1996, pp. 355-365.

Anson, Chris A., and Jessie Moore, editors. Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer. The WAC Clearinghouse and University Press of Colorado, 2016, wac.colostate.edu/books/ansonmoore/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2018.

Bazerman, Charles, et al. Taking the Long View on Writing Development. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 51, no. 3, 2017, pp. 351-60.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State University Press, 2007.

Belcher, Wendy. Writing Your Journal Article in Twelve Weeks: A Guide to Academic Publishing Success, Sage, 2009.

Berg, Maggie, and Barbara K. Seeber. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy. University of Toronto Press, 2016.

Bergmann, Linda, and Janet Zepernick. Disciplinarity and Transfer: Students’ Perceptions of Learning to Write. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no. 1/2, 2007, pp. 124-49.

Bromley, Pam, et al. Transfer and Dispositions in Writing Centers: A Cross-Institutional Mixed-Methods Study. Across the Disciplines, vol. 13, no. 1, 2016, wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/articles/bromleyetal2016.pdf. Accessed 11 July 2018.

Cranton, Patricia. Professional Development as Transformative Learning: New Perspectives for Teachers of Adults. Jossey-Bass, 1996.

---. Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning: A Guide for Educators of Adults. Jossey-Bass, 2006.

Cranton, Patricia, and Kathleen P. King. Transformative Learning as a Professional Development Goal. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, vol. 2003, no. 98, 2003, pp. 31-38.

DasBender, Gita. Liminal Space as a Generative Site of Struggle: Writing Transfer and L2 Students. Anson and Moore, pp. 273-98.

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning FYC as Intro to Writing Studies. College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no. 4, 2007, pp. 552-84.

Downs, Douglas, and Liane Robertson. Threshold Concepts in First-Year Composition. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 105-121.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Roger Powell. States, Traits, and Dispositions: The Impact of Emotion on Writing Development and Writing Transfer Across College Courses and Beyond. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, compositionforum.com/issue/34/states-traits.php. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions. Writing and Transfer, special issue of Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Eodice, Michele, et al. The Meaningful Writing Project: Learning, Teaching, and Writing in Higher Education. Utah State University Press, 2016.

Fife, Jane. Composing Focus: Shaping Temporal, Social, Media, Social Media, and Attentional Environments. Composition Forum, vol. 35, 2017, compositionforum.com/issue/35/composing-focus.php. Accessed 13 Nov. 2018.

Fredricks, Jennifer, A., et al. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Review of Educational Research, vol. 74, no.1, 2004, pp. 59-109.

Gay, Geneva. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Teachers College Press, 2000.

Girod, Mark, et al. Appreciating the Beauty of Science Ideas: Teaching for Aesthetic Understanding. Science Education, vol. 87, no. 4, 2003, pp. 574-587.

Graham, Steve, Karen R. Harris, et al. Improving the Writing Performance, Knowledge, and Self-Efficacy of Struggling Young Writers: The Effects of Self-Regulated Strategy Development. Contemporary Educational Psychology, vol. 30, no. 2, 2005, pp. 207-241.

Graham, Steve, Debra McKeown, et al. A Meta-Analysis of Writing Instruction for Students in the Elementary Grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 104, no. 4, 2012, pp. 879-896.

Hartman, Yvonne, and Sandy Darab. A Call for Slow Scholarship: A Case Study on the Intensification of Academic Life and Its Implications for Pedagogy. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, vol. 34, no. 1-2, 2012, pp. 49-60.

Heddy, Benjamin C., and Kevin J. Pugh. Bigger Is Not Always Better: Should Educators Aim for Big Transformative Learning Events or Small Transformative Experiences? Journal of Transformative Learning, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015, pp. 52-58.

Heddy, Benjamin C., and Gale M. Sinatra. Transforming Misconceptions: Using Transformative Experience to Promote Positive Affect and Conceptual Change in Students Learning about Biological Evolution. Science Education, vol. 97, no. 5, 2013, pp. 723-744.

---. Transformative Parents: Facilitating Transformative Experiences and Interest with a Parent Involvement Intervention. Science Education, vol. 101, no. 5, 2017, pp. 765-786.

Heddy, Benjamin C., et al. Making Learning Meaningful: Facilitating Interest Development and Transfer in At-Risk Students. Educational Psychology, vol. 37, no. 5, 2017, pp. 565-581.

Inoue, Asao B. Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future. Perspectives on Writing. The WAC Clearinghouse and Parlor Press, 2015, wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/inoue/. Accessed 13 Nov. 2018.

Inoue, Asao B., and Mya Poe, editors. Race and Writing Assessment. Peter Lang, 2012.

King, Kathleen P. The Handbook of the Evolving Research of Transformative Learning Based on the Learning Activities Survey. Information Age Publishing, 2009.

Koskey, Kristen L.K., et al. Applying the Mixed Methods Instrument Development and Construct Validation Process: The Transformative Experience Questionnaire. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 12, no.1, 2018, pp. 95-122.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, vol. 32, no. 3, 1995, pp. 465-491.

Land, Ray, et al. Editor’s preface: Threshold Concepts and Transformative Learning. Meyer et al., pp. ix-xlii.

Meyer, Jan H. F., and Ray Land, editors. Overcoming Barriers to Student Learning: Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge. Routledge, 2006.

---. Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Issues of Liminality. Meyer and Land, pp. 19-32.

Meyer, Jan H. F., et al., editors. Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning. Sense Publishers, 2010.

Mezirow, Jack. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. Jossey-Bass, 1991.

Moore, Jessie L. Five Essential Principles about Writing Transfer. Understanding Writing Transfer: Implications for Transformative Student Learning in Higher Education, edited by Jessie L. Moore and Randall Bass, Stylus, 2017, pp. 1-12.

Moore, Jessie. Mapping the Questions. Writing and Transfer, special issue of Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, compositionforum.com/issue/26/map-questions-transfer-research.php. Accessed 10 Aug. 2018.

Moore, Jessie L. and Chris M. Anson. Introduction. Anson and Moore, pp. 3-13.

Perkins, David N. Constructivism and Troublesome Knowledge. Meyer and Land, pp. 33-47.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. Teaching for Transfer. Educational Leadership, vol. 46, no.1, 1988, pp. 22-32.

---. Transfer of Learning. International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed., edited by T. N. Postlethwait and T. Husen, Pergamon Press, 1992, pp. 6452-6457.

Poe, Mya. Re-framing Race in Teaching Writing across the Curriculum. Across the Disciplines, vol. 10, no. 3, 2013, wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/race/poe.pdf. Accessed 13 Nov. 2018.

---. Review: Writing across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing by Kathleen Blake Yancey, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak. The WAC Journal, vol. 25, 2014, pp. 145-49.

Poe, Mya, et al., editors. Writing Assessment, Social Justice, and the Advancement of Opportunity. Perspectives on Writing. The WAC Clearinghouse and University Press of Colorado, 2018, wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/assessment/. Accessed 13 Nov. 2018.

Pugh, Kevin J. Newton’s Laws Beyond the Classroom Walls. Science Education, vol. 88, no. 2, 2004, pp. 182-196.

---. Teaching for Transformative Experiences in Science: An Investigation of the Effectiveness of Two Instructional Elements. Teachers College Record, vol. 104, no. 6, 2002, pp. 1101-1137.

---. Transformative Experience: An Integrative Construct in the Spirit of Deweyan Pragmatism. Educational Psychologist, vol. 46, no. 2, 2011, pp. 107-121.

Pugh, Kevin J., Cassendra M. Bergstrom, et al. Teaching for Transformative Experiences in Science: Developing and Evaluating an Instructional Model. Journal of Experimental Education, vol. 85, no. 4, 2017, pp. 629-657.

Pugh, Kevin J., Lisa Linnenbrink-Garcia, et al. Motivation, Learning, and Transformative Experience: A Study of Deep Engagement in Science. Science Education, vol. 94, no. 1, 2010, pp. 1-28, doi:10.1002/sce.20344.

Robertson, Liane, Kara Taczak, and Kathleen Blake Yancey. Notes Toward a Theory of Prior Knowledge and Its Role in College Composers’ Transfer of Knowledge and Practice. Writing and Transfer, special issue of Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012. compositionforum.com/issue/26/prior-knowledge-transfer.php. Accessed 13 Nov. 2018.

Rueda, Robert. Cultural Perspectives in Reading: Theory and Research. Handbook of Reading Research, edited by Michael L. Kamil, et al., Routeledge, vol. 4, 2010, pp. 84-103.

Salomon, Gavriel, and David N. Perkins. Rocky Roads to Transfer: Rethinking Mechanisms of a Neglected Phenomenon. Educational Psychologist, vol. 24, no. 2, 1989, pp. 113-142.

Sinatra, Gale M. The ‘Warming Trend’ in Conceptual Change Research: The Legacy of Paul R. Pintrich. Educational Psychologist, vol. 40, no. 2, 2005, pp. 107-115.

Snead, Robin. ‘Transfer-Ability’: Issues of Transfer and FYC. WPA-CompPile Research Bibliographies, vol. 18, 2011, comppile.org/wpa/bibliographies/Bib18/Snead.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Taczak, Kara. 5.4 Reflection is Critical for Writers’ Development. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 78-81.

Timmermans, Julie A. Changing Our Minds: The Developmental Potential of Threshold Concepts. Meyer, pp. 13-19.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Creative Repurposing for Expansive Learning: Considering ‘Problem-Exploring’ and ‘Answer-Getting’ Dispositions in Individuals and Fields. Writing and Transfer, special issue of Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, compositionforum.com/issue/26/creative-repurposing.php. Accessed 12 July 2018.

---.Understanding ‘Transfer’ from FYC: Preliminary Results of a Longitudinal Study. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no. 1/2, 2007, pp. 65-85.

---. What Is Transfer? A Rhetoric for Writing Program Administrators, edited by Rita Malenczyk, Parlor Press, 2013, pp. 143-55.

---, editor. Writing and Transfer, special issue of Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, compositionforum.com/issue/26/. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and Linda Adler-Kassner. Metaconcept: Writing Is an Activity and a Subject of Study. Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 15-16.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and Doug Downs. Reflecting Back and Looking Forward: Revisiting ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions’ Five Years on. Composition Forum vol. 27, 2013, compositionforum.com/issue/27/reflecting-back.php. Accessed 13 Nov. 2018.

---. Writing about Writing: A College Reader. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2011.

---. Writing about Writing: A College Reader. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2014.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and Nicolette Mercer Clement. Double Binds and Consequential Transitions: Considering Matters of Identity during Moments of Rhetorical Challenge. Anson and Moore, pp. 161-179.

Winzenried, Misty Anne, et al. Co-Constructing Writing Knowledge: Students’ Collaborative Talk across Contexts. Composition Forum, vol. 37, 2017, compositionforum.com/issue/37/co-constructing.php. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Yancy, Kathleen Blake, et al. Writing across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State UP, 2014.

Extending the “Warming Trend” from Composition Forum 41 (Spring 2019)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/41/transformative-experiences.php

© Copyright 2019 Sandra L. Tarabochia and Benjamin C. Heddy.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 41 table of contents.