Composition Forum 33, Spring 2016

http://compositionforum.com/issue/33/

Toward a Technical Communication Made Whole: Disequilibrium, Creativity, and Postpedagogy

Abstract: This article details how we integrate Jody Shipka’s approach to creativity and rhetorical awareness into a Professional Writing, Rhetoric, and Technology major at the University of South Florida. We situate Shipka’s pedagogy alongside postpedagogy, differentiating the latter from postcomposition. In short, we argue that postpedagogy echoes educational theory that insists upon the importance of disequilibrium. We then report how our students respond to our disequilibrating pedagogy, collecting survey responses via an IRB approved study. We hope these responses can help instructors interested in our postpedagogical notion of creativity anticipate and prepare for student discomfort and resistance—to recognize the fine distinction between productively confused and hopelessly lost. With that goal in mind, we conclude by addressing difficult questions of assessment.

Introduction

This article details how we perceive the relationship among postpedagogy, creativity, and technical communication. A major inspiration for this article is Jody Shipka’s Toward a Composition Made Whole. Shipka argues for an approach to multimedia composing that moves away from emphasizing recognizable finished products in favor of developing a robust rhetorical awareness and material process that can be applied across a range of mediums, genres, and situations. To make composition “whole” for Shipka is to prioritize rhetorical and material awareness by stressing the importance of “flexibility, adaptation, variation, and metacommunicative awareness” over the “acquisition of discrete skills […] that are often and erroneously treated as static and therefore universally applicable across time and diverse communicative contexts” (83). Her emphasis, then, is not so much on producing final products as it is on cultivating a conscious and repeatable familiarity with the composing process. In fact, this process might produce objects less familiar to either teacher or student.

Shipka realizes this cultivation via what we term a disequilibrating pedagogy, one that subverts students’ expectations for clear instructions and “to do” checklists. Below, we argue that Shipka’s approach resonates with postpedagogy, and we seek to position her among myriad theorists working with and through that term. Despite their differences, postpedagogical theorists are generally united in their commitment to student-directed learning, to crafting assignments and environments that force students to articulate their own concerns that shape the purpose, audience, and/or medium of their work. We will flush out postpedagogy further below; for now, we would maintain that Shipka certainly reflects this preliminary definition. We would point to her refusal to supply students with “a list of non-negotiable steps that must be accomplished in order to satisfy a specific course objective,” which is based on her belief that

[…] students who are provided with tasks that do not specify what their final products must be and that ask them to imagine alternative contexts for their work come away from the course with a more expansive, richer repertoire of meaning-making and problem-solving strategies. (101)

We agree with Shipka’s argument that working outside the expectations and forms of established genres expands students’ creative capacity, autonomy, and their ability to negotiate ambiguity, skills that are particularly useful in the current hyper-competitive job market. A 2013 Hart Research Associates survey, conducted on behalf of the Association of American Colleges and Universities, suggested that these are skills employers value: when asked whether creativity and innovation were key to their companies’ future success, 92% of employers agreed, with 51% agreeing strongly (4). Further, 71% of employers believed that colleges should do more to develop students’ creative capacity (9). A postpedagogical orientation drawing on Shipka’s rhetorical/material approach can help with such creative development.

However, as Shipka acknowledges, there is a harrowing dimension to this imaginative, holistic approach; asking students to move away from the established and the familiar inevitably produces disequilibrium, a venerable concept in Education that receives less acknowledgement in Rhetoric and Composition. Educational theorists in the tradition of Dewey, Freud, Piaget, and Erikson advance the notion that transformative, educational experiences require disturbing or destabilizing a student’s understanding (Mortola 46). Paul Lynch, speaking directly to the postpedagogical movement, advocates for paying more attention to Dewey’s notion of “inquiry” as a form of experimentation and reflection: “Inquiry begins when a problem arises, when something is out of joint. Method begins when some new experience upsets the way of proceeding we have constructed from previous experience. We have a situation on our hands when our habits no longer seem to serve” (82). Lynch’s explication of Dewey captures a fundamental assumption of both Shipka and postpedagogy: that inquiry and disequilibrium are necessary to push students to engage and invent rather than simply perform or execute.

The first section of this article offers a more comprehensive explication of postpedagogy and the central role disequilibrium plays in it. Highlighting its connection to Shipka’s rhetorical materialism, we frame postpedagogy as an ecological and complex approach to learning that begins by rejecting authoritative models of teaching (whether the authority is a teacher, an assignment sheet, or a recognizable genre). In what follows, we argue that such a method requires a degree of disorientation, which is an unavoidable dimension of all education—but perhaps especially unavoidable for professional and technical communication programs that hope to foster the confidence, autonomy, and ingenuity associated with creative thought and production. We would also suggest that the need for such a pedagogy is all the more urgent in an educational milieu increasingly structured around corporate standardization and mass assessment, one in which “learning” often means memorization and regurgitation.{1} Our dedication to disequilibrium and creativity advances from the question: “How we can get students to think outside the box if they are so accustomed to filling in circles?”

In addition to responding to our own institutional context (which we discuss in the section that follows), we would position postpedagogy as a response to the broader socio-political and institutional changes in America’s primary and secondary education systems. We are concerned by the impact corporate and politically driven standardization is having upon our students. As scholars such as Sir Ken Robinson speculate, today’s “McDonaldist” (Ritzer) curriculum leaves little room for imaginative exploration or productive play. Robinson directly challenges the extent to which contemporary education at the primary and secondary levels has become dedicated to providing the right answers rather than asking meaningful questions, going as far as to assert that contemporary education, structured around a skill and drill mentality, is actually killing creativity. He worries that students are treated as products coming off an assembly line and advocates for curricular reform that prioritizes identifying and developing each student’s idiosyncratic interests and abilities. We believe postpedagogy and the rhetorical materialism Shipka advocates pays heed to Robinson’s warning and responds to his call to prioritize creative thinking and imaginative capacity.

In short, any program that seeks to prepare students to be creative and innovative members of the workforce can and should incorporate disequilibrium into their curriculum. The second section of this article reports on how we incorporate this radical perspective into courses in the Professional Writing, Rhetoric, and Technology major at the University of South Florida. In addition to laying out assignments, this article surveys students’ responses to our postpedagogical approach. Given an increased awareness of the debilitating anxiety students face, we felt it important to craft a study that shared student reactions to our intentionally distressful approach. We used an IRB approved Google Doc to survey a total of 42 students regarding both their rhetorical and creative choices and their attitudes toward the class as a whole: 22 in Marc’s New Media for Technical Communication course and 22 in Megan’s Advanced Composition course, with 2 students enrolled in both courses. Of the 22 potential participants in each course, 19 completed each of the course-specific surveys. Overall, of the 42 potential participants from both courses, 30 completed the general survey.{2} While many of the students reported initially feeling some measure of disequilibrium or discomfort, most concluded that the course made a significant impact on their creative capacity and what Shipka would refer to as their rhetorical and material awareness.

We hope explicating this theoretical approach, sharing these ambiguous assignments, and surveying and offering our insights into students’ responses can help instructors interested in our postpedagogical notion of creativity anticipate and prepare for student discomfort and resistance. Reflecting upon her experiences in one of Marc’s classes, Kristen N. Gay characterized postpedagogy as an attempt to walk the line between “productively confused and hopelessly lost” (Santos et al.). This article attempts to illuminate how we trace and negotiate that fine line. What we explore, then, is why we insist upon confusion, how we create confusion, and how and why our students respond to this confusion favorably and productively.

Postpedagogy, Creativity, and/as Disequilibrium

In order to build a classroom space to foster such productive confusion, following Shipka, we advocate for a robust notion of creativity that draws upon our 3000-year rhetorical tradition, one that takes as its postulate that invention and creativity are neither innate capacities nor mechanistic formulas. In the spirit of Bruno Latour’s Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam, we would like to avoid (as much as possible) the bottomless “critical” hole of whether creativity can be “taught.” Our discussion focuses instead on attending to the conditions in which we believe creativity can best be “cultivated,” which, via Nathaniel A. Rivers, we approach as an ecological process rooted in student experience (and, we would add, failure). In the same way that Rivers' ecological and material articulation of cultivation presses against the stagnant binary of nature and culture, we would propose cultivation in/as education as a way of moving beyond the teacher-student binary. Learning is a complex, ecological, and distributed activity that cannot be reduced to a primary causal agent (no matter how many times curricular reforms such as NCLB or Common Core tell us that learning is simply a function of “good teaching”). Further, following Thomas Rickert’s exposition of a Heideggerian invention based on attunement to the particular affordances of a specific situation, we conceptualize creativity as a “mood,” a way of being in the world, one that encourages us to foster at least a tolerance for the unfamiliar if not an appreciation for the strange. By insisting on a disequilibrating dimension to our projects, we are insisting that such cultivation and/or attunement requires unknown risks and at least a dash of discomfort.

By advancing Shipka’s and Rickert’s moves toward opening space to sometimes painful creative work, we do not mean to say that creativity is absent from professional and technical writing programs, nor do we view the implementation of creativity in these courses as impoverished. Rather, because creative thinking is often conflated with critical thinking and developed via the use of case studies, we would argue that current approaches to helping students exercise their creative capacity can be augmented. Like technical communication programs and teacher/scholars, technical professionals—including engineering professionals, teachers, and researchers—recognize the value of creativity for working technical professionals of all stripes (Saha, et al.; Samadi; Selinger). However, among the much-lauded "soft skills" (writing and communication skills, the ability to work well in groups, creative problem solving, etc.) needed to complement scientific and technical abilities, creativity is among the most valuable but also the most difficult to teach and assess (Maiden, et al.; Nichol; Samadi; Setiadi, So, and Suprayitno). In working to help students develop a capacity for creativity, then, we advocate an approach that complements the existing emphasis on critical thinking but that moves beyond recognizable genres and conventions. Given the experimental nature of these compositions and the institutional need for assessment, the concluding section of this piece addresses the specific difficulties that disequilibrium engenders in regards to assessment.

The earliest use of postpedagogy traces back to Gregory L. Ulmer’s Derridean-inspired pedagogy, which he later developed into a theory of electracy (see Ulmer). Like Derridean poststructuralism, “electracy” seeks to deconstruct the logocentric basis of literacy, eschewing mastery, clarity, abstraction, objectivity, and knowledge in favor of prioritizing chance, enigma, materiality, subjectivity, and affect (see Arroyo, Santos et al., Santos and Browning). After Applied Grammatology, the term receives sparse attention until appropriated by Rickert. Rickert, drawing upon the psychoanalytic theory of Lacan and Žižek, deploys the term in opposition to traditional cultural studies pedagogies that seek to directly confront or transform students’ ideologies. Such pedagogies, Rickert argues, attempt to “master” critical thinking and fail to recognize the extent to which ideological confrontation produces resistance, cynicism, and performance—which together often further entrench students in reactionary ideological frameworks. Rickert’s relevance to our discussion concerns how, in the same way that cultural studies pedagogies attempt to master and thus subvert critical thinking, prescriptivist, heuristically-driven pedagogies attempt to master and thus subvert creativity. More recently, scholars (Arroyo, Lynch, Santos et al., Santos and Browning, and Santos and Leahy) have extended Rickert’s postpedagogical framework beyond cultural studies pedagogies to ask how it might more broadly inform composition theory. In this article, we look to extend this conversation by bringing postpedagogy to professional and technical writing.

We would distinguish the inventive, disruptive goals of postpedagogy—and particularly Shipka’s cultivation of a rhetorical and material notion of process—from other contemporary movements in composition theory, especially Sidney Dobrin’s “postcomposition.” We feel it productive to begin by distinguishing postpedagogy from postcomposition because highlighting their differences will do much to expose postpedagogy’s core commitments. While the two movements share a prefix, they advocate for almost antithetical aims. Dobrin’s postcomposition purports to liberate writing studies from its dominant and, in Dobrin’s eyes, dogmatic insistence upon pedagogy. We believe Dobrin’s aversion to pedagogy is dangerous for the economic stability and scholarly work of our field and undervalues the importance of pedagogy to the professional development of both teachers and students. In Postcomposition, Dobrin argues that the pedagogical imperative threatens to stagnate, or perhaps even destroy, composition as an intellectual pursuit (190-91). In contrast to postcomposition’s move toward the study of “writing-without-students,” (Dobrin 15), in the introduction to Beyond Postprocess, Dobrin, Rice and Vastola frame postpedagogy as “interested in questions and theories of writing not trapped by disciplinary expectations of the pedagogical” (14). Paul Lynch stresses that many who consider themselves postpedagogical wouldn’t share the characterization of pedagogy as a trap, even if they would likely “share a wariness and a weariness with any desire to discern the one true [pedagogical] method” (6). We consider ourselves among the latter. First, we reject the notion that pedagogy distracts us from other possible articulations of writing studies. Second, given the political and economic stakes, we believe turning away from pedagogy would be willfully self-destructive. Pedagogy plays a major role in sustaining the job market for Rhetoric and Composition scholars and keeping English departments financially solvent (it is also, of course, a meaningful and rewarding intellectual and ethical pursuit). Third, and central to our discussion of postpedagogy, creativity, and disequilibrium, we insist that postpedagogy is not a move away from the activity of teaching: if anything, it is an intensification of it.

As Lynch stresses, there is no end to the pedagogic conversation. By deconstructing the myth of the One, True, Pedagogy; by insisting that pedagogy is an ecological, co-creative, experiential act that unfolds with students (Hawk, Santos and Leahy); and by emphasizing that pedagogy, because it is a vital or choric activity (Hawk, Santos and Browning), cannot be mastered, willed, planned, or controlled (Vitanza, Davis, Rickert, Santos and Leahy), postpedagogy reminds us that teaching and learning are part of yet another “interminable” conversation (Burke). Further, we wholeheartedly endorse Lynch’s notion that pedagogy is what occurs after and not before a class (95). Following Lynch, we would argue that if a teacher’s idea of pedagogy concerns generating a detailed plan of what will happen and expecting a class to turn out exactly like that plan, then that teacher has missed the point. Instead, pedagogy is an anticipation of what might occur, a readiness to respond to what is unfolding, and an ability to reflect on an experience and form a new anticipation for a future possibility. It is always a process of trial and error that must be recalibrated for every new class and every new student. It is this recalibration to each individual student and class that marks postpedagogy as an ethical activity (Davis, Hawk, Santos). Thus, the form of creativity we hope to instill in our students—one predicated on the inevitability of disequilibrium—is also the practice of creativity we exercise in our own teaching.

In order to develop such a methodological approach to pedagogy that both 1) insists that pedagogy be reinvented anew for every class and every student and 2) insists that such a process is unsustainable without in some way inventing from past successes and failures, Lynch turns to Dewey’s philosophy of experience. Lynch’s notion of experience resonates with the reflective work endorsed by Shipka and is central to the rhetorical and compositional processes we outline below. However, we disagree with Lynch’s assertion that postpedagogy has been overdetermined in its efforts to undermine more formulaic notions of pedagogy and has not developed a philosophy of experience, or method of reflection, that can prolong and develop such methodological discussions (see especially 58-59). Of course, Shipka offers a robust example of putting postpedagogy into practice. As a further example, we would point to Byron Hawk’s detailed explication of how heuristics operate in a postpedagogical context.{3} Hawk stresses that “students need to develop their own schemata to fit their particular topics and situations” and that “if teachers give students the schemata first, their goal should be to revise those schemata as a part of the invention process rather than to follow them prescriptively” (192). In his conclusion, Hawk expands on what he identifies as a complex, vitalist, ecological approach to composition:

In the context of composition pedagogy, teachers need to build smarter environments in which students work. […] These environments are constellations of architectures, technologies, texts, bodies, histories, heuristics, enactments, and desires that produce the conditions of possibility for emergence, for invention. Heuristics, then, cannot be reduced to generic, mental strategies that function unproblematically in any given classroom situation. They are enacted in particular contexts and through particular methods that reveal or conceal elements of a situation and enable or limit the way students interact with and live in that distributed environment. (249)

In Postpedagogy and Web Writing, Santos and Leahy contrast two similes to explicate Hawk’s ecological call: rather than thinking of ourselves as chefs training apprentices, we might think of ourselves as architects designing kitchens; it isn’t our job to teach as much as it is our job to design environments (and assignments) in which students can learn. A third example worthy of mention would be Santos and Browning’s work on multimodal composer Maira Kalman and choric invention. That article, in addition to articulating a distributed theory of invention commensurate with postpedagogy, discussed one of the assignments detailed below, including examples and explication of student work. Our emphasis in this article, very much influenced by Hawk and reinforced by Shipka, concerns forcing students to encounter and negotiate uncertainty while working within ambiguous constraints that themselves generate productive confusion.

Ambiguous Constraints: Moving Towards a Postpedagogical Creative Practice

We realize that this extended discussion of postpedagogy might feel out of place in an article focusing on creativity and professional and technical writing, but we hope it is apparent that postpedagogy isn’t merely a discussion regarding teacher preparation, curricular development, or classroom management. Rather, it is fundamentally an exploration of the contextual and environmental conditions that foster invention and creativity and an insistence on approaching learning as a creative act. Such topics have clear value to technical communication. We would suggest, however, that Hawk’s insistence upon transforming rubrics is trickier than it sounds. To return to our postulate: knowing how to transform/translate a heuristic and being capable of undertaking that process are not innate abilities. Creativity isn’t something a student merely has. Rather, creativity is a capacity that can be and must be cultivated and exercised. Furthermore, we can never know to what extent our students’ previous education, interests, and experiences have prepared them to take the creative leap; we cannot simply assume that they are ready or capable to make that leap. The difficult work of building creative capacity requires confidence and a willingness to face the discomfort of working outside an established genre and stepping outside a comfort zone—hence our interest in incorporating Shipka’s rhetorical materialism into postpedagogy and incorporating both those movements into the major in which we work.

Our contribution to USF’s Professional Writing, Rhetoric, and Technology program involves preparing students to navigate the adversity and alterity that creativity requires. We believe, and our student surveys affirm, that students will be better prepared to enact the contextual revisionary heuristic process outlined by Shipka and Hawk only after having worked without the productive constraints that a heuristic or genre offers. This is why we provide students with “ambiguous constraints,” because going through the process of inventing genre conventions for a new genre better prepares them for recognizing and transforming conventions in existing genres.

The major in which we work is vocationally focused: its primary aims involve preparing students for pursuing jobs in today’s complex and technological economy. Our student population is demographically similar to the university as a whole, though we have higher percentages of African American (12.6% of majors vs. 11.1% of USF students) and Hispanic students (23.5% of majors vs. 19.9% of USF students). We also have a higher proportion of female students (65.9% of majors vs. 55.3% of USF students) than the university as a whole. Additionally, like the larger USF student body, many of our students hold full- or part-time jobs outside the university. Students are required to take four core courses: Introduction to Technical Communication, New Media for Technical Communication, Visual Rhetoric for Technical Communication, and Advanced Composition. These courses culminate in an internship program, coordinated by Michael Shuman, who has done an excellent job cultivating sponsors and placing students in valuable positions. And while our small faculty limit the number of electives we offer, the major offers electives in Professional Writing, Advanced Technical Writing, Grant Writing, Rhetoric of Science, and Rhetoric and Gaming. However, because there is no prerequisite system in place for the major, students come into our courses with vastly different levels of technical proficiency.

With an eye toward the vocational focus of the program, we ground our courses in technological skills that are applicable to other courses and to potential jobs, especially in social media and web-based writing. Given this vocational investment, we often determine for students the medium or technologies they will use for a specific project. This distinguishes our pedagogy from that of Shipka, whose focus on robust rhetorical awareness involves students making informed rhetorical decisions regarding medium. For Shipka (2013) determining in advance what mediums a student will have to use to complete a project severely impinges upon their rhetorical invention (see especially 84-87). While we acknowledge that it is something of a concession to select the medium, we believe we can realize her aspirations by having students work outside the boundaries of recognized genres. As we document below, the open-ended and downright cryptic nature of our assignments call for students to make a number of informed rhetorical decisions throughout the composing process, and our use of a postmortem form, similar to Shipka’s SOGC (statement of goals and choices, 113-17),{4} develops their ability to identify, explicate, reflect, and learn from the composing experience. We borrow the term postmortem from the video game industry, where it signifies a reflective process through which one dissects a creative endeavor. Recalling our discussion of Lynch, reflection, and method above, the goals of the postmortem process concern identifying successes and failures that can be applied to future projects. Or, in terms that recall Lynch’s explication of Dewey, it is this reflective process that transforms experience into inquiry. It is this ability to explicate their process that grounds our belief, a belief supported by student reflections, that a creative emphasis benefits their work in other courses.

In order to better understand this creative emphasis, it might be easiest to explicate what we mean by ambiguous constraints via a concrete example. In Marc’s New Media for Technical Communication class, one assignment asks, in its totality, for students to “make me a map that is not a map.” Students are presented with a list of readings that intend to stimulate them toward identifying the genre conventions of a typical map. The map assignment, like all assignments in both Marc and Megan’s classes, requires students to complete postmortem forms that ask them to articulate their intentions, methods, trials, and successes in decoding our ambiguous assignments. As part of their reflective work, students must answer both “in what ways is this a map?” and “in what ways isn’t this a map?” Students are left to sift through the provided materials and conduct additional research in anticipation of these questions. The focus is often on identifying how students negotiated ambiguity (in this case, in what ways isn’t their map a map?).

In the next section, we survey student responses on these postmortem forms. These responses by and large support our initial hypothesis and Shipka’s previous findings: that disequilibrium does help students develop robust rhetorical awareness and increases their creative abilities. However, in the course of collecting and coding this research, we began to focus on how many students addressed the harrowing dimensions of this process. In Toward a Composition Made Whole, Shipka warned:

Indeed, making the shift from highly prescriptive assignments to those that require students to assume responsibility for the purposes and contexts of their work can prove challenging for students accustomed to thinking about and accounting for the work they are trying to accomplish in curricular spaces (104).

While “harrowing” might be a strong term, the anxiety of students, who steadfastly believe in a concrete connection between classroom grades and future employment, is both real and deep. We are not insensitive to the anxiety this approach produces. After having read Shipka’s essay “This was (NOT) an Easy Assignment,” one of our students concisely captured the frustrations associated with this challenge: “Although I think that Shipka’s method has merit, it is very hard and frustrating to unlearn 15 years of schooling.” We appreciate this comment both for how it acknowledges the value of creativity and at the same time supports Robinson’s suspicion that school itself might be one of the major factors eroding students’ creative capacities. In what follows we report and reflect upon student responses to two projects in our classes, and to our postpedagogical approach as a whole.

Methods

Students in Marc’s class were asked to “make me a Kalman with a side of Rice” (http://www.marccsantos.com/2014227new-media-week-8-kalman-and-rice/) while students in Megan’s class were asked to “make a PechaKucha and make me think of Rice.” (http://meganmmcintyre.com/socialmedia.html).{5} In Marc’s class, students were asked to read Maira Kalman’s And the Pursuit of Happiness. In both cases, students were asked to read Jeff Rice’s Digital Detroit, which emphasizes how the personal experience of a particular place can interrupt the commonplace assumptions we might hold toward it. In other words, invention and creativity are often tied to specific, material, embodied experiences and are not mere matters of thought; because Santos and Browning (2014) have already offered a detailed explication of this project and its classroom context, we will not replicate that here. In both cases, this was the third assignment of the semester, so students were more comfortable and familiar negotiating such ambiguous constraints. Marc’s students, previously asked to “make me a MEmorial that is not a memorial” and to “make me a map that is not a map,” already had experienced transforming heuristics/genres to specific circumstances. The third assignment ratchets up the difficulty by asking them to extract a genre and create conventions out of far less familiar texts. Similarly, Megan’s students had previously been asked to create a definitional “text” (in which they define either rhetoric, technology, or social media in a medium of their choice) and had completed a semester-long blog project. While Megan’s projects were not quite as intentionally ambiguous as Marc’s, her students also had previous experience in choosing and/or inventing genres and establishing expectations.

To get a sense of what these projects look like, we would direct you toward Seth’s testament to Baltimore (A Kalman with a side of Rice http://www.sethwrites.com/academic/) and/or David’s relationship to church (A PechaKucha that makes me think of Rice https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VN52n-iRmsg). Of course, not all students will compose something with the rhetorical sophistication or production quality of these works. We do not mean for them to be representative; nor do we want to present and explicate extensive examples of student work. This article isn’t so much about highlighting our students’ work as it is in exploring their reactions to its process and encouraging other programs in writing studies and professional and technical communication to cultivate more assignments that ask students to invent a new box to think outside of.

During the 13th week of the semester, after they submitted their third projects, students were asked to complete 2 surveys (see Appendix) via Google Forms. First, students completed a course- and project-specific survey; these surveys were extended versions of postmortem assignments that are typical in both courses. Again, the postmortems offer students an opportunity to reflect on the process by which they produced their projects and allow us, as teachers, to better understand the goals and learning process that is crystallized in the final product. For the purposes of this study, Marc’s class-specific survey consisted of 10 questions about their assignment to “Make me a Kalman with a side of Rice”; Megan’s class-specific survey consisted of 9 questions about their assignment to “make a PechaKucha and make me think of Rice.” After completing these initial surveys, students from both courses completed a second general survey about their experiences with the course. None of the surveys collected identifying information about the respondent; however, because the course-based surveys asked students to describe their projects, it would be easy to connect names to those responses. The general survey, however, includes no identifying information and, because students aren’t asked to describe their topics or work, there is no way to connect responses to particular students. Since both courses met in a computer lab, many students were able to complete one or both of the surveys during class time. Additionally, for absent and tardy students as well as those who were unable to complete the surveys during the allotted class time, a link was posted in an announcement on each course’s Canvas site. Following the completion of the Spring 2014 semester, we analyzed the responses to all three surveys paying special attention to students’ assessments of our assignments, articulations of discomfort, and sense of their own development, especially in terms of creative thinking, over the course of the semester.

Findings

Student responses suggest three major findings: first, students found themselves breaking rules and exploring new physical and intellectual spaces during the completion of these projects and throughout the course. Second, students believed that the vague nature of these projects and the lack of explicit constraints encouraged them to express a kind of creativity not necessarily required by other projects in other courses. Finally, students reported that our vague assignments produced anxiety and fear, but most students ultimately found this anxiety productive.

As part of the class-specific surveys, we asked both groups of students about their composing processes. Many students described the programs and technologies used to build their final multi-modal projects. Some students, however, described their process in less technological terms: One student argues that, as opposed to beginning with an argument or research, the lack of formalized constraints or expectations for the project forced her “to go from the heart”; another student revealed that her process began with “being creative with just my camera and the city.” In addition to exploring new modes of creative invention, some students remarked on the fact that, because of their focus on place, these projects also often involved putting themselves in new physical spaces. As one student notes, “[this project] makes the students get out of the house, go somewhere and explore, and learn about things hands on. This is one of very few projects in my five years at USF that has made me do this.”

As they explored new spaces and genres, students also became more comfortable articulating the rhetorical dimensions of their own work. One student describes the goal of her project as “attempting to communicate to my audience the pure feeling of a particular commonplace,” while another argues that he “want[ed] my project to make you feel some kind of way, not any particular way, just some kind of way.” A third student saw the goals of his project as even more complex: “It attempts to go beyond the metanarrative that is currently attached to the place. It attempts to communicate that Hyde Park is not just a place for rich, happy people, but a dynamic network of often conflicting stories.” Though the assignment directions do not discuss these rhetorical goals for the projects, students’ processes forced them to make difficult rhetorical choices, choices the postmortem surveys asked them to articulate and reflect upon—choices, we believe, that will benefit them in future classes and in their careers.

In addition to investigating new spaces, by and large, the students surveyed in both courses believed our assignments led to creative, inventive work: of the 30 students who responded to the general survey, 26 students used some version of the word “creative” or “creativity” to describe their work in the class, with students describing the work as alternately “creative,” “frustrating,” and “adventurous” and asserting that the course helped them develop “new ways to learn” and “a new way of thinking.” In particular, students believed that the lack of specific genre expectations “allowed for creativity to spark.” Students also noted that the lack of articulated constraints “gave the project both an intense freedom and a set of new limitations.” Ultimately, as one student commented, these projects succeeded in “mak[ing] you think for yourself and ‘pave your own way’ in a sense. Instead of hearing ‘follow this outline’ it was ‘create your own outline, just be sure to include this thing somewhere in it.’ It is more open-minded and causes students to open their minds more.”

The vast majority (27 of 30 or 90%) of students who responded to the general survey said they would recommend the course to their peers, and 26 of 30 respondents believed that the skills they developed in the course would be applicable to other courses or to their future careers. While we expected a number of students to recognize the creative value in these assignments, we were a bit surprised that virtually all of them, 26 out of 30, made this case, especially because this question and these responses came from the anonymous survey, so it is less likely that this is a matter of social desirability bias. And the fact that our end-of-semester course evaluations affirmed these positive responses only further supports our conclusion that the overwhelming majority of students recognized the benefits of being productively confused.

Toward a Productive Anxiety

The process of developing these (hopefully) transferable skills, however, was, for many students, a painful and anxiety ridden one. As one student noted, the technological processes posed challenges in and of themselves: “all of the projects had their equal share of frustrations and triumphs based primarily on the restrictions and imperative choices that came with the use of diverse (and on my part, mostly unexplored) communication mediums.” Additionally, the unfamiliar process of invention and the lack of concrete instructions made students feel “hopeless,” “nervous,” and “anxious.” Most students, though, found that this anxiety eventually gave way to productive engagement with the project. One noted that “[feelings of] hopelessness have found a way to generate constructive work.” Another admits, “I was lost, but not for long. As soon as I became actively engaged in the project, I started to find solutions. And each answer found spurred a bunch of ideas to follow.” Further, many students commented on the freedom that these projects allow. One such student says, “I had the freedom to do more than I would have if I had the constraints that come with specific instructions. I had the freedom to come up with my own way of approaching each project. And while it was very stressful, I feel I was more productive than I had been before, where I just gave teachers what they asked me for.” Ultimately, then, student responses suggest that despite widespread discomfort with the projects (29 of 30 respondents identified feeling frustration, anxiety, and/or confusion), the disequilibrium that characterizes the course assignments led to productive, creative experiences and inventive work. As one student noted, “At the beginning of the semester, …people weren't ‘riding the line between’ as much as they were falling into pits of ‘hopelessly lost.’ The result of this was a lot of frustration that started out rather unproductive, but through experience, was transformed into productive.”

How are we able to transform initial anxiety into this kind of appreciation? Here we would recall Lynch and Hawk: it is because our own postpedagogical method requires that we listen to students. We will conclude by explicating two ways in which we have learned to listen. The first is quite literal, and the second concerns our commitment to reflective work (what we call postmortems, what Shipka terms SOGC). Generally speaking, there is a moment each semester with each student that goes something like this:

Student: So, what does Ulmer mean by Memorial?

Teacher: I don’t know, what do you think he means?

Student: Well, something something.

Teacher: Yeah, that sounds about right. So what does that mean/tell us/encourage us to do?

We don’t mean to trivialize our role here. We place extensive energy into the construction of an environment in which this conversation can take place (and, as we document below, in assessing these unfamiliar works). However, the pivotal, postpedagogical moment in developing creativity often involves us disappearing for the student, becoming as empty as one of Socrates’s interlocutors, so that the “philosopher” can do her thinking out loud. We need to be there in that moment, with a willingness to listen and the restraint not to answer for the student. Developing this restraint is not easy.

Creativity, Disequilibrium, and Assessment

Since at least the publication of Kathleen Yancey’s 2004 CCCC’s keynote address, Rhetoric and Composition scholars have addressed the added complications of assessing new/digital/multi- media assignments. We do not have the space to review the entirety of this discussion (McKee and DeVoss provide a thorough and contemporary overview), but we would suggest that adding a “harrowing” dimension to assignments only further complicates multimedia assessment. In her recent piece “Assessing Scholarly Multimedia,” Cheryl Ball explains that, when introducing students to multimedia composition, “I begin by defining the kinds of texts we are focusing on. Until one answers the what, one cannot answer the how (do we assess?)” (62). Because we attempt to cause disequilibrium by refusing to define the kinds of texts students might produce, the “what” is often what we are asking our students to imagine and invent. As one student who felt hopelessly lost wrote:

What makes it painful or hopeless, in my opinion, is the connection between projects and grades. The possibility of getting a bad grade because you misinterpreted an assignment can be very nerve wracking [sic], especially when ‘follow the directions’ is something heavily emphasized to students since elementary school.

We would begin responding to this student by affirming their discomfort: we recognize that student anxiety is exacerbated by the connections between this disequilibrating work and grades that impact students’ GPAs, scholarships, and future life prospects. Ball recommends developing flexible rubrics built around concepts such as creativity, research, form, and creative realization, which are quite similar to the kinds of rubrics we often end up collaboratively building with our students. Megan works with her students—approximately two weeks before the project is due— to build a heuristic/rubric by which she evaluates their work on the project.

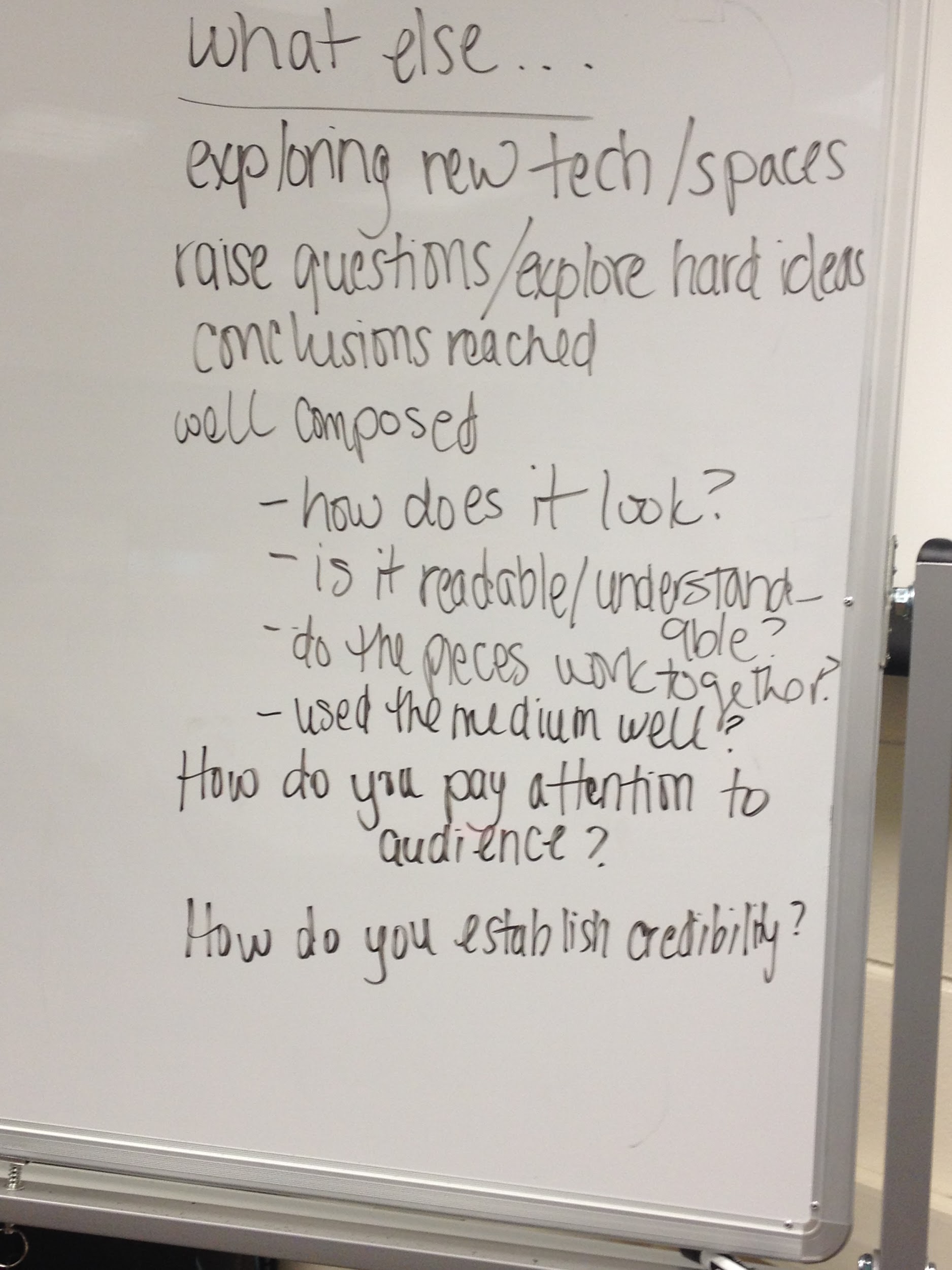

Figure 1. The rubric for Megan’s Definitional Text Project.

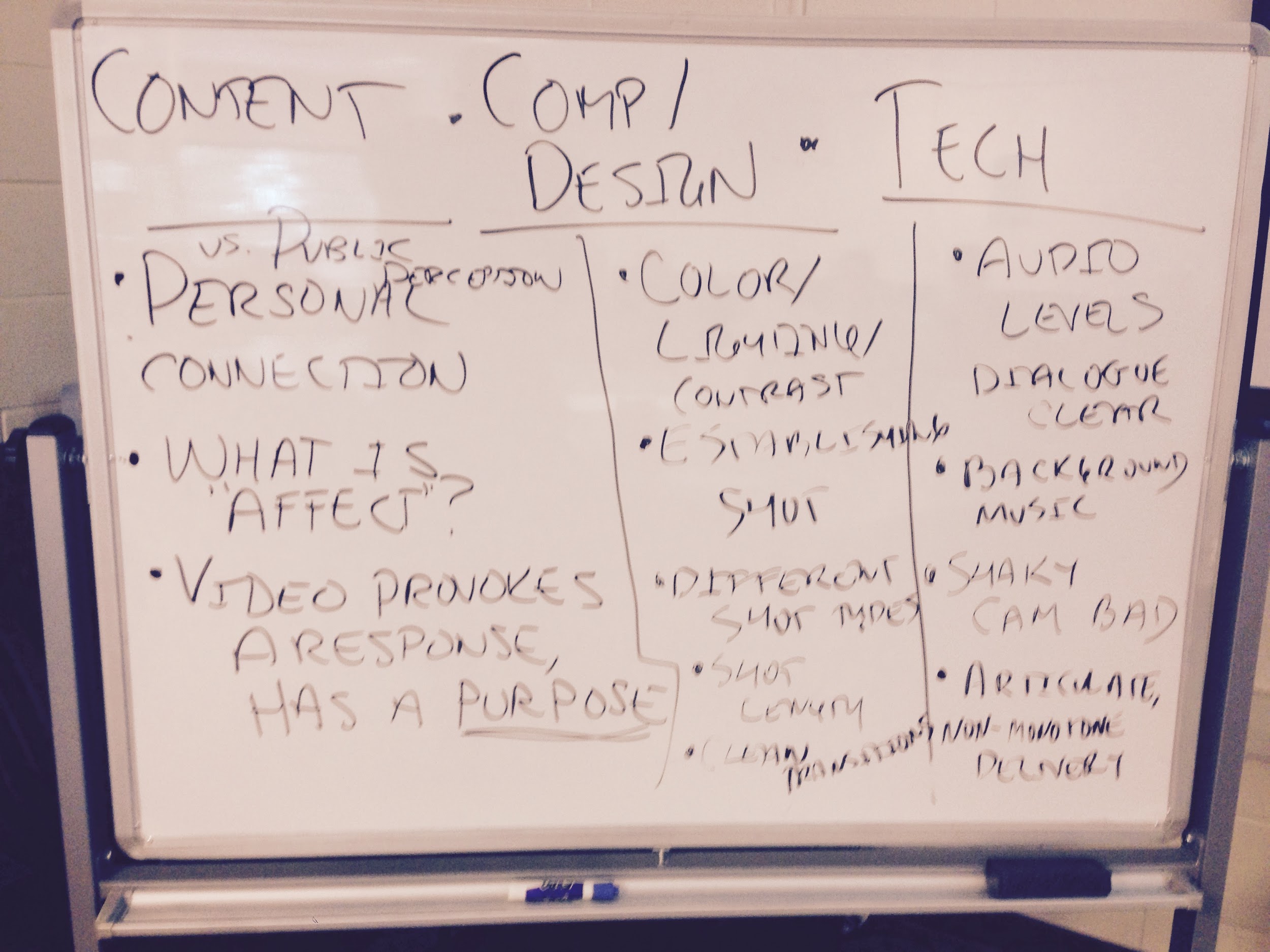

Figure 2. The rubric for Marc’s Affective Object project, based on Kalman’s recent book My Favorite Things.

Students brainstorm these criteria in small groups (in Marc’s case, students had previously read both Kalman’s My Favorite Things and a few theoretical pieces on affect). Then the class works through each group’s suggestions, synthesizing them into a series of questions, concerns, or criteria. This heuristic/rubric also forms the foundation for the postmortem’s direct questions on their intended audience and purpose, their workflow, and their decision-making. Thus, students have the opportunity to articulate how their project fulfills the assignment and meets the standards established by the class. This co-creation of the rubric and, by extension, of the postmortem questions, helps to build trust: students know what Megan is looking for because they decide with her what the evaluative criteria should be.

We would frame this distress, then, at least in part as a matter of trust. Specifically, we want the students to trust us when we tell them that we will reward authentic investment and effort. We measure investment and effort not only in the quality of the project, but also in the depth of the postmortem forms, measuring the detail and sophistication with which students can discuss their creative choices and justify their rhetorical decisions. Especially early in the course, many suspect that we are playing a game of “gotcha!” and that we evaluate their projects against some preconceived expectations for what constitutes a Kalman with a Side of Rice. In class, after watching Seth’s Baltimore video above, one particularly frustrated student asked, “well, if that’s what you wanted, then why didn’t you just show me that in the beginning?!” Marc tried to explain to the student that he didn’t realize what Seth made was a possibility—that he didn’t really have an idea for what a Kalman with a side of Rice might be until Seth showed him what it might look like. And while many students at some point share this student’s complaint, our findings show how most reach a place where they recognize the long-term benefits of short-term frustration. They not only trust in us to be fair in our evaluations of their work, but also to provide them with an ultimately pragmatic educational experience.

Ultimately, it is the process of reflection—the postmortem—that transforms the unpredictable creative moment into (perhaps) a repeatable method. This is the heart of Shipka’s articulation of a pedagogy made whole: that the process by which the students create their own constraints and genres is more important than the final product. Our postmortem assignments— like Shipka’s SOGC forms—allow students to articulate their process and provide a rationale for creating what they did in the way they did. It allows them the opportunity to articulate how they coped with the confusion our assignments provoked. The postmortems also provide students with an opportunity to tell us what we might have missed. They provide additional complexity and criteria for negotiating a grade. In some cases, a particularly persuasive postmortem can make up for what might initially appear as an unimpressive project. Sometimes students articulate a symbolic meaning that wasn’t immediately apparent; other times they delve into how much time they invested learning a new technology or nuanced skill. We want to reward students for the various investments they make because, if we agree that developing the robust material and rhetorical awareness Shipka articulates involves taking risks, then we must also acknowledge that it can involve failure. Postpedagogy doesn’t want to penalize failure when it is in service of developing increased creative capacity. The postmortems play an integral role in distinguishing productive failure, and allowing us to reward it, which in turn helps to dissipate student anxiety.

Conclusion

In this piece, we have advocated for a postpedagogical approach to teaching creativity in professional and technical writing classes by moving outside traditionally recognized heuristics and genres. We hope this has demonstrated the extent to which Shipka’s notion of a “composition made whole” responds directly to Lynch’s call for postpedagogical theorists to place more emphasis on method—particularly on methods that help transform the unpredictability of experience into a tentative and reflexive methodology. Throughout, we acknowledge how this approach distresses students but steadfastly maintain that such distress is essential to learning. We negotiate this distress by “being there” for our students, by face-to-face interaction that testifies to our investment in their success, and involving them in developing methods for assessment. We also believe that the reflective process helps them analyze their own anxiety, and frame their own confusion in productive terms.

We would here conclude by stepping a bit beyond the framework of this piece. Our investment in disequilibrium stems from a postulate that a student’s ability to inhabit (as Rickert might term it) epistemic or pedagogic alterity transfers to their ability to negotiate ethical alterity. In helping them negotiate unfamiliar situations, we also help them negotiate unfamiliarity in general. We frame the ability to handle alterity, difference, and the anxiety they produce as we think of creativity: as muscles that can be increased through training and exercise. Let classrooms be gymnasiums for such growth.

Appendix: Surveys

Survey #1: Questions on our Class as a Whole (Santos’ and McIntyre’s classes)

Please take your time in thinking about and responding to the following questions. These questions should take 20-25 minutes to complete.

- For Santos' class only: You have recently read Jody Shipka’s “This Was (NOT) An Easy Assignment.” In 5-7 sentences, tell me about Shipka’s argument and her methods.

- For Santos' class only: You have completed 3 assignments working with a professor who appreciates Shipka’s approach. Do you think Shipka’s approach has merit? Why or why not?

- This class hopes to foster productive frustration and creative problem solving, to ride the line between productively painful and hopelessly lost. How are we doing in that regard?

- How are the projects and assignments experienced in this class different (or similar) from other assignments in your Professional Writing, Rhetoric, and Technology classes? Or from other writing-oriented classes you have taken at USF?

- Do you think the approach you have developed in this class is applicable to other writing contexts (either other writing classes, your current/future career, or both)?

- Out of the two (for McIntyre's class) or three (for Santos' class) projects completed thus far this semester, which one was your favorite? Which one would you consider the most successful? Why?

- Out of the two (for McIntyre's class) or three (for Santos' class) projects, on which did you learn the most this semester? Please identify the project and what you feel you learned planning, executing, and or/sharing that project.

- What was the biggest challenge you faced this semester?

- Would you recommend a peer take this course? Why or why not?

Survey #2: Make Me A Kalman with a Side of Rice Postmortem (Santos’ Class)

Instructions: Please take your time in thinking about and responding to the following questions. These questions should take 30-40 minutes to complete.

- In 5-7 sentences, please describe your project to me: what it is attempting to communicate?

- How did your research proceed? What information did you collect?

- Tell me about your technical process for composing this piece. What technologies did you use? What resources did you use? How did you work with your materials? What revisions did you make?

- Thinking particularly about your process, what was one important choice you made during the composition process?

- What is your favorite part of the project?

- What part of the project would you change? Or what part of your process would you have done differently?

- In 5-7 sentences, tell me about Maira Kalman’s work.

- How did Kalman’s work inspire or influence your project? What specific elements of your work echo or transform Kalman’s?

- In 5-7 sentences, tell me about Jeff Rice’s project.

- In what way does your project offer “a side of Rice”?

Survey #3: “Make a PechaKucha and make me think of Rice” Postmortem (McIntyre’s Class)

Please take your time in thinking about and responding to the following questions. These questions should take 20-25 minutes to complete.

- In 5-7 sentences, please describe your project to me: what it is attempting to communicate?

- Tell me about your composing process: How did you decide on a place? Where did you get your images? What program did you use? Did you create the slideshow first or your voiceover?

- Tell me about your technical process for composing this piece. What technologies did you use? What resources did you use? How did you work with your materials? What revisions did you make?

- Thinking particularly about your process, what was one important choice you made during the composition process?

- What is your favorite part of the project?

- What part of the project would you change? Or what part of your process would you have done differently?

- In 2-3 sentences, tell me about how the PechaKucha form impacted your work.

- In 5-7 sentences, tell me about Jeff Rice’s project.

- In what way does your project attempt to “make me think of Rice”?

Notes

- Here we do not mean to castigate all forms of assessment, but are targeting the “prepackaged” curricula that are being developed and sold by for-profit corporations that do not reflect the disciplinary awareness or adaptability of other projects, such as USF’s MyReviewers (http://myreviewers.com/) or MSU’s ELI Review (http://www.elireview.com/about-2/). As we discuss in our conclusion, assessment is a serious concern for any pedagogy structured around fostering disequilibrium. (Return to text.)

- 2 students were enrolled in both courses; these students each completed the course specific survey for both courses and responded only once to the general survey about the two classes. Appendix A contains the postmortem forms used to collect student responses. Links to course websites, including syllabi and assignments, are available from http://www.marccsantos.com/?page_id=43 and http://meganmmcintyre.com/socialmedia.html. (Return to text.)

- There are other examples (in fairness, many appearing concurrently to or shortly after the publication of Lynch’s work) that further demonstrate pragmatic instantiations of postpedagogical methods. Notably absent from Lynch’s work is a discussion of Ulmer, who has crafted two “textbooks,” Internet Invention (2003) and Electronic Monuments (2005), that rigorously detail a postpedagogical curriculum. Santos et al. (2014) offers a case study of a graduate seminar working through/with Internet Invention. More recently, we would point to Arroyo (2013) for a discussion of postpedagogy and video and Santos and Leahy (2014) for a discussion of postpedagogy and web writing as a 21st century approach to teaching expository writing. (Return to text.)

- Shipka notes that the SOGC builds upon a longstanding tradition of reflective writing in R/C, pointing specifically to Elbow and Belanoff’s (1989) work on “writing about writing.” What distinguishes her approach, she argues, is that the SOGC focuses on questions of material processes and technical tools in addition to rhetorical awareness. We wholeheartedly endorse her argument that:Knowing that they will eventually need to account for their goals and the rhetorical, technological, and methodological choices they make in service of these goals, students are provided with an incentive to consider how, why, when, and for whom their texts make any kind of meaning at all. (116) (Return to text.)

- For further discussion of Marc’s assignment, Maira Kalman, and Jeff Rice, see Santos and Browning (2014). Santos and Browning demonstrate how Kalman’s aesthetic philosophy and works resonate with choric invention, a mode of invention often associated with postpedagogy. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Arroyo, Sarah J. Participatory Composition: Video Culture, Writing, and Electracy. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP, 2013. Print.

Ball, Cheryl E. Assessing Scholarly Multimedia: A Rhetorical Genre Studies Approach. Technical Communication Quarterly 21:1 (2012): 61-77. Print.

Burke, Kenneth. Philosophy of Literary Form. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, 1973. Print.

Hawk, Byron. A Counter-History of Composition / Toward Methodologies of Complexity. Pittsburgh, PA: U of Pittsburgh P, 2007. Print.

Latour, Bruno. Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern. Critical Inquiry 30.2 (Winter 2004): 25-48. Print.

Lynch, Paul. After Pedagogy: The Experience of Teaching. Urbana, IL: National Council for Teachers of English, 2014. Print.

Maiden, Neil, et al. Requirements Engineering as Creative Problem Solving: A Research Agenda for Idea Finding. Requirements Engineering Conference (RE). Sydney, NSW. Sept. 2010. Web. 19 Feb. 2015.

Mortola, Peter. Sharing Disequilibrium: A Link between Gestalt Therapy Theory and Child Development Theory. Gestalt Review 5.1 (2001): 45-46. Print.

Nichol, Sophie. Emergence of Creativity in Learning Via Social Technologies. ISTAS 2010: Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society: Social Implications of Emerging Technologies. 7-9 June 2010, Piscataway, NJ: IEEE, 2010. Print.

Rickert, Thomas. Acts of Enjoyment. Pittsburgh, PA: U of Pittsburgh P, 2007. Print.

---. Ambient Rhetorics: The Attunement of Rhetorical Being. Pittsburgh, PA: U of Pittsburgh P, 2013. Print.

Ritzer, George. The McDonaldization of Society. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 1993. Print.

Rivers, Nathaniel A. Rhetorics of (Non)Symbolic Cultivation. In Ecology, Writing Theory, and New Media: Writing Ecology. Ed. Sidney Dobrin. New York: Routledge, 2012. 34-50. Print.

Robinson, Sir Ken. Out of Our Minds: Learning to be Creative. North Mankato, MN: Capstone, 2011. Print.

Saha, Shishir Kumar et al. A Systematic Review on Creativity Techniques for Requirements Engineering. 2012 International Conference on Informatics, Electronics & Vision (ICIEV). Dhaka, Bangladesh, May 2012.

Samadi, Saeed. Fostering Creativity and Innovation for Organizations in a Turbulent Environment for Long-Term Survival. International Summer Conference of Asia Pacific Business Innovation and Technology Management (APBITM). Dalian, China, July 2011.

Santos, Marc C. How the Internet Saved My Daughter and How Social Media Saved My Family. Kairos 15.2 (2011). Web. 19 Feb. 2015. <http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/15.2/topoi/santos/index.html>.

Santos, Marc C. and Ella R. Browning. Maira Kalman and/as Choric Invention. Enculturation 2014. Web. 19 Feb. 2015. <http://enculturation.net/kalman-choric-invention>.

Santos, Marc C., et al. Our Electrate Stories: Explicating Ulmer’s Mystory Genre. Kairos 18.2 (2014). Web. 19 Feb. 2015. <http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/18.2/praxis/santos-et-al/index.html>.

Santos, Marc C. and Mark H. Leahy. Postpedagogy and Web Writing. Computers and Composition 32 (2014): 84-95. Print.

Selinger, Carl. The Creative Engineer: What Can You Do to Spark New Ideas?. IEEE Spectrum 41.8 (2004): 47-49. Print.

Setiadi, Nugroho J., Idris Guatama So, and E.A. Suprayitno. Assessing Creativity Skill Development in Art and Design among Undergraduate Students: Implementing Creative Potential Simulation Software to Capture Creativity-Relevant Personal Characteristics. IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment and Learning for Engineering (TALE). Bali, Indonesia, Aug 2013.

Shipka, Jody. Toward a Composition Made Whole. Pittsburgh, PA: U of Pittsburgh P, 2011. Print.

Shipka, Jody. This Was (NOT!!) an Easy Assignment. Computers and Composition Online 2007. Web. 19 Feb. 2015. <http://www2.bgsu.edu/departments/english/cconline/not_easy/intro/index.html>.

Ulmer, Gregory L. Internet Invention: From Literacy to Electracy. New York, NY: Longman, 2003. Print.

Ulmer, Gregory L. Electronic Monuments. Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota P, 2005. Print.

Ulmer, Gregory L. Applied Grammatology. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins UP, 1985. Print.

Vitanza, Victor J. Three Countertheses; or, A Critical In(ter)vention into Composition Theories and Pedagogies. In Contending with Words: Composition and Rhetoric in a Postmodern Age. Ed. Patricia Harkin and John Schilb. New York: Modern Language Association, 1991. 139-72. Print.

Yancey, Kathleen. Made Not Only in Words. College Composition and Communication 56.2 (2004): 297-328. Print.

Toward a Technical Communication Made Whole from Composition Forum 33 (Spring 2016)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/33/techcomm.php

© Copyright 2016 Marc C. Santos and Megan M. McIntyre.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 33 table of contents.