Composition Forum 46, Spring 2021

http://compositionforum.com/issue/46/

Retention and Persistence in Writing Programs: A Survey of Students Repeating First-Year Writing

Abstract: Student retention and persistence is increasingly prioritized by state and local policies as well as national scorecards and rankings—however, the policies that politicians and administrators undertake to improve university metrics tend to ignore the realities faced by students at the heart of our institutions. Drawing on a survey/interview project involving 67 students repeating first-year writing classes at a diverse institution in the Southwestern US, this article takes a student-centered approach to understand the reasons they drop first-year writing, such as health concerns, lack of engagement with the curriculum, and their incompatibility with online learning or poorly taught online classes. In making recommendations to address the challenges students face, the author calls on writing teachers and administrators to take a more activist stance in their roles, by engaging in actions such as pushing back against exploitative working conditions, recognizing the racism inherent in strict attendance policies, drawing on work from directed self-placement to better guide students when considering online writing classes, and advocating for readings and curricular choices that take into account the diversity of students in writing programs.

In 2016, the President of Mount St. Mary’s College made headlines by comparing at-risk students “to bunnies that should be drowned or killed with a Glock” as he implemented a survey for first-year students. The survey aimed to identify students who might lower St. Mary’s graduation and retention numbers so they could be recommended to drop out before reporting deadlines. The survey asked for students’ individual ID numbers and included questions such as whether they felt depressed in recent weeks, whether they had a learning disability, or how confident they were in their families financing their education. Two faculty members (one tenured) who spoke out against this initiative were fired for not sufficiently supporting the institution’s retention initiative (Jaschik). While this is an egregious example of how far an institution might go to boost its numbers for college rating systems such as U.S. News and World Report Best Colleges or the Department of Education College Scorecards created under the Obama administration, this behavior isn’t particularly surprising.

On the surface, goals to increase retention and graduation rates are admirable—as Complete College America (CCA) has stated on its website, “we’re leveraging our Alliance and implementing strategies around the country to close achievement gaps, boost graduation rates and ensure every student has the opportunity to achieve their dreams.” Nonetheless, as Linda Adler-Kassner illustrates, a darker reality lies behind the rhetoric of these organizations in which well-endowed educational foundations are increasingly trying to shape educational systems to their preferred way. Due to work by organizations like CCA, state governments have increasingly turned to performance-based funding for their colleges and universities, providing motivation to give bonuses to administrators who boost these numbers even if it means potentially pushing more students out of four-year institutions and into two-year ones to boost numbers.

Teachers and administrators in writing programs shape the educational experiences of most first-year college students, and consequently, they should play an important role in these discussions and in advocating for better ways to support student success. Drawing on existing literature both in writing studies as well as a study conducted with students repeating first-year writing classes at Southwest University,{1} this article explores why students drop out of writing classes and what writing programs can do to help make their classes more supportive places for the students that enter them.

Foundational Retention Work

Vincent Tinto has long been considered a central figure in the retention literature since his development of a theory of dropout in the 1970s, which focused on the importance of integrating an individual student into the institution: “the process of dropout from college can be viewed as a longitudinal process of interactions between the individual and the academic and social systems of the college” (94). In later years, he moved away from the term “integration” as he shifted his interests to supporting initiatives like first-year learning communities to help students form bonds with students and professors (Wolf-Wendel et al.).

Another influential voice has been Alexander W. Astin, who conducted a study of more than 20,000 students and 25,000 faculty at 200 institutions that explored what factors correlated with student success and graduation rates. For instance, he discovered that some of the following correlated with student success:

-

Living on campus

-

Leaving home to attend college

-

If working, working on campus

-

Social connections with friends/professors

-

Engagement in learning

-

Teaching-oriented institution and student-oriented faculty

-

Financial support

Astin also found that students who hadn’t completed their bachelor’s degree in four years but were still enrolled had characteristics more like the students who have dropped out. While Astin’s findings have been used in positive ways to promote more community building and faculty training, they have often been used to promote policies that privilege a particular type of student. For instance, SU made it less expensive for students to enroll in 15 credit hours rather than 12. At the state level, full-time for scholarship eligibility was defined as 15 credit hours instead of 12. Later, SU implemented a dorm residency requirement for first year students. Incidentally, while instituting the above-mentioned retention initiatives, the state cut funding for the coveted lottery scholarship, which meant that it no longer covered 100% of tuition at SU.

Push Back: Calls for Larger Institutional Transformations

Many scholars have pushed back against a narrow view of existing retention scholarship and the policies associated with it. For instance, Alberto F. Cabrera et al. found that ability to pay had a negative impact on student persistence and had a moderating effect on educational aspirations—even if a student is highly motivated, the positive impact of this motivation will not be as strong if a student perceives significant financial barriers. Laura I. Rendón et al. critiqued existing retention initiatives like learning communities or additional tutoring because of their emphasis on helping minoritized students conform to institutional expectations rather than focusing on “the total transformation of colleges and universities from monocultural to multi-cultural institutions” (138).

Within writing studies, we have seen similar criticisms. Citing Astin, Pegeen Reichert Powell (Retention; Hospitality) reminded us that retention and graduation rates tend to correlate with the characteristics of entering students—more selective institutions have higher retention and graduation rates. She further argued that schools should not be ranked on a simple graduation metric that fails to account for entering characteristics because more inclusive institutions will always appear to be weaker on these metrics—a more nuanced look might reveal a different reality. For instance, the Higher Education Research Institute found that although public institutions have significantly lower overall graduation rates, they can be more effective at graduating non-traditional students than private institutions (DeAngelo et al.).

Along these lines, Powell has critiqued institutions’ narrow focus on improving retention numbers, noting that some students will always drop out, and argued that writing faculty should instead focus on educating students while they are with us—she explained this shift:

I was less concerned with preparing students for future academic or professional writing than I was with inviting students to understand, in new ways, the varied rhetorical contexts in which they were already participating—including, but not limited to, the writing they were doing in the other courses they were taking that semester. (Retention 137)

Instead of obsessing on whether or not a student is going to continue, Powell has taken a stance of “absolute hospitality,” namely that we should meet students where they are and help them with their goals, whether those goals involve completing a university degree or not (“Hospitality”). Elsewhere, Sara Webb-Sunderhaus argued that access is not enough and that institutions need to “attend to the holistic development of the student” and “intentionally tie the curriculum to students’ lives outside the classroom” (Access 110).

Rita Malenczyk expressed concerns that many retention efforts could have more sinister impacts, which we saw with the aforementioned Mount St. Mary’s survey initiative: “I argue, however, that implemented uncritically, retention efforts can turn a university into a panopticon, a Foucauldian instrument of power and control that reflects a fear of the disorder that often accompanies human agency and human development.” (25). In short, perspectives from this angle have called out institutions’ reluctance to engage in more robust transformations to become more radically inclusive, instead focusing on policies to improve their metrics which are bolstered as more and more university presidents have bonuses in their contracts for improving graduation rates.

Pedagogical Innovations and Writing Class Connections to Student Retention

Beyond these more critical approaches, researchers, teachers, and administrators in writing programs have largely approached retention from a pedagogical angle, with much of the early work occurring in developmental writing programs concerned with supporting students who have traditionally been categorized as “at risk.” For instance, work out of ASU by Gregory Glau and Sarah Elizabeth Snyder has documented the role their stretch program has played in supporting student success—Snyder noted that mainstream students in Glau’s original study, as well as her follow up study on who took Stretch, are passing English 101 at higher rates than their non-stretch counterparts. In later work at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, Polina Chemishanova and Robin Snead have reported that pass rates in the first semester writing class increased from 72% to 87% with their PlusOne studio model, even though many students in that program were traditionally considered “at risk.”

Writing programs often play a role in supporting first-year learning communities, with FYW classes paired with courses in other disciplines with the idea that they can support student writing development in more specialized areas (Zawacki and Williams). In a different vein, Michael Day, Tawanda Gipson, and Christopher P. Parker created a unique peer support program at Northern Illinois University where FYW students were paired with Peer Advocates who played a variety of roles: “They held pizza parties, led study sessions, connected students to campus resources, invited students to campus events, contacted students on social media, helped with group work in class (including preparation for the annual Showcase of Student Writing), and helped students register for classes the following semester” (243). While the authors found some early successes with their pilot, they noted at the end of their chapter that the program had been cut due to budget pressures. This is a reminder that programs thoughtfully designed to promote student retention take resources to support and are consequently less attractive to budget-focused administrators than policies such as requiring students to live on campus and take more credit hours.

In thinking about student retention, just focusing on passing rates in first-year writing classes is not enough. Perhaps the more important question, at least from the perspective of upper administration, is the role first-year writing success plays in predicting overall student success. While noting that any one course may not have a causal relationship to graduation rates, Garrett, Bridgewater, and Feinstein found that:

students who fail the writing sequence have the lowest predicted graduation rate. Students who fail WRIT 100 (the most basic remedial writing course) have only a 17 percent predicted graduation rate. Failing WRIT 111 (Academic Writing) or WRIT 112 (Research Writing) reduces a student’s chance of graduation by 38 percent, more than any other first-year class.

Consequently, with research telling us that success the first year in college is important for long-term student success and Garrett, Bridgewater, and Feinstein’s finding that passing or failing a writing course is a strong predictor of students’ likelihood of graduation, then helping students be successful in first-year writing should be on all administrators’ minds.

Methodology

In order to build on the student-centered approach valued in writing studies and among writing program administrators, this article works from the perspective of what institutions and its agents can do to better support their students rather than simply how students can conform to their institutions. On this note, I am drawing on the definition used by the editors in the 2017 collection, Retention, Persistence, and Writing Instruction, which distinguishes between retention and persistence:

Retention is an institutional approach—and one that perhaps too often loses sight of student learning, interests, and motivations while focusing on the statistical and financial importance of each retained student. Student persistence, though, is in many ways the mirror opposite of retention. This term is most often identified with Vincent Tinto’s work; it situates agency differently than does retention and assumes that students have a variety of reasons for continuing in higher education, or not. Using both these terms, as we do in the title, reflects our belief that that continued student learning and engagement in college is a mutual responsibility that involves actions by both institutions and students. (Ruecker et al. 4)

Alongside these terms, I also reference student success, which I use to refer more specifically to a student passing their writing class. In this article, I conceive of student success in writing courses as a mutual responsibility between students and their instructors, with the understanding that student investment in a classroom and learning experience is shaped by choices made by institutions, programs, and individual instructors.

The design of this study and subsequent analysis of data was guided by the following research questions:

-

What impacts student retention and success in writing courses?

-

What first-year writing policies and pedagogical practices support or hinder student retention and success?

I chose a mixed-methods approach, combining an initial survey of 67 students followed by interviews with 11 participants. A mixed-methods approach enables researchers to get the breadth of responses provided through surveying a larger number combined by in-depth data provided via interviews that can provide additional clarity about particular issues (Johnson and Christensen).

After obtaining IRB approval, I contacted SU’s enrollment office to request email addresses for the following population of students: “18 and older, taking ENG 101 or 102 for the second or additional time because they failed or dropped the course a previous semester.” I made this request each semester for four semesters, receiving lists of 150-200 students each time.{2} While I advertised a drawing for a $25 gift card each semester for participating, response rates were generally low at approximately 10% with an unusually high number the 4th semester:

-

1st semester: 15 respondents

-

2nd semester: 11 respondents

-

3rd semester: 15 respondents

-

4th semester: 26 respondents

The surveys asked participants if they wanted to participate in an interview—47 of 67 respondents agreed to this, although I only conducted interviews with 11 due to time and resource limitations and/or the students’ failure to reply to scheduling emails.

Excluding the consent page and the email/interview request at the end, the survey included 19 questions divided into a few different sections. The introductory section had questions about what course they were repeating and why they were repeating the course. The next section asked about their previous course—why they struggled, whether it was online or face-to-face, how often the course met and what time of day it met, and an open-ended question asking for any additional information they’d like to share. Next, participants were asked similar questions about their current course, including what had changed or what they were doing differently and how confident they felt about passing. The final section asked about demographics, which were listed last because putting these early on can make a student more conscious about how they’re responding. Interviews were based around students’ survey responses, aiming to ask more depth of their previous and current experiences and recommendations they had for the institution to improve the success of students like them. They lasted anywhere from 22 to 60 minutes, with an average of 35 minutes.

I first analyzed the survey responses, looking at frequency counts for the various multiple-choice questions and cross-tabulating responses for certain questions to see if students from different ethnic/racial/language groups had different responses. I recursively read through the open-ended responses, identifying major categories and grouping responses into them—since some responses contained multiple themes, some were grouped into multiple categories.

While transcribing the interviews, I kept analytical memos to identify trends and a preliminary list of codes. I subsequently coded all the transcripts using an open-source program called TAMS Analyzer, which enabled me to see if specific codes were appearing across different participants and to quickly recall passages that referenced a particular theme. As is common with an inductive coding approach, I ended up adding additional codes during the coding process for a total of 31, ranging from basic demographic data (e.g., age) to external factors (e.g. family, housing, lifechange) to self-perception (e.g. motivationengagement, selfperception) to information about why they dropped (e.g., whydropped, work, workload, online).

Survey Findings

Survey respondents were generally reflective of SU’s demographics as a Hispanic-Serving Institution and a majority student of color institution: 40% Latinx, 27% white, 15% Native American with small percentages identifying as Asian, Black/African American and “Other.” The one exception with these numbers is that the Native American population is roughly double the percentage in this sample compared to the actual institutional population. The respondents were 57% female and 43% male, and 21% identified as speakers of English as a second/additional language.

When asked why they had to repeat a writing class, 35 (53%) reported that they withdrew from the previous course, 23 (34%) received a C- or lower (a C is a passing grade), and the remaining 10 chose “other”—one of these “Other” responses simply noted they received a withdrawal grade. The remaining “Other” responses fell primarily into three broad categories. Two students referenced institutional bureaucracy (e.g., credit did not transfer). Three referenced health concerns:

I’m repeating ENG 101 for a third time due to health issues which caused me to be dropped from the first two attempts. I had no difficulties with the class, but unforeseen sickness prevented me from attending class, and though I completed the work on time and submitted it through email, the course instructors still felt it necessary to drop me from their course with a WP (Withdrawal Passing) and W respectively.

Four responses referenced the content or professor, with comments such as “lectures are mundane and unproductive” and “We read very old American History-esque, overrated books and their matching movie lucky enough to be produced by someone who really gave a damn about Huckleberry Finn etc. back in the 50s.” The following response was especially disconcerting:

I got dropped from the class at SU, because I got laughed at by other students for answering a question wrong. I was told that I knocked over a cup of hot coffee near the professor while I was leaving in a hurry and in great distress and he thought it was intentional. I was feeling extreme embarrassment and wanted to leave before crying in front of everyone. I am not a typical high school graduate from the larger cities...I come from a rural town, where I faced many difficulties learning in high school by teachers who did not want to teach, so I dropped out. I eventually taught myself at home and earned my GED.

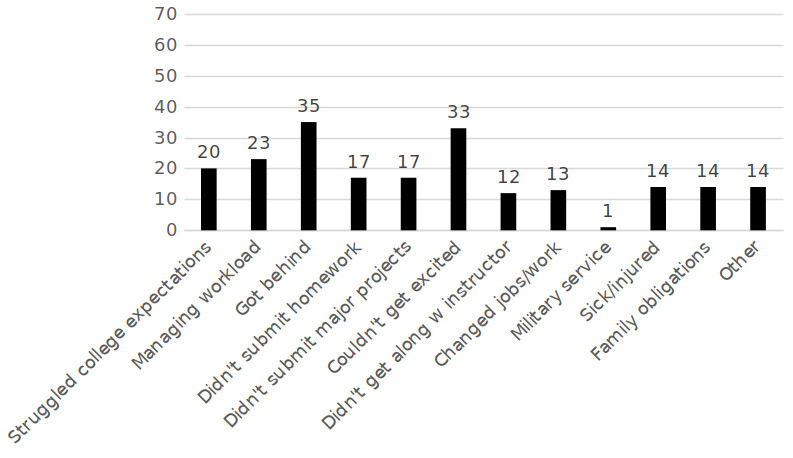

It is clear that this student, already nervous at college coming from a small school in a small town, did not feel comfortable in his writing classroom and that this incident drove him away. Participants were asked to provide more information on why they dropped in a related question. As evident in Figure 1, the most common responses were falling behind or struggling to get excited about the material. Among those who chose “Other” and provided written responses, seven focused on frustrations with structure and content (e.g., “The material was very dry and went by slowly, while the instructor hardly ever gave assessments. We had very few, so for example, in the first exam, we didn’t know what he was expecting and many of us didn’t do well. The whole semester was a struggle to figure out how he wanted things and by then, I’m pinning my entire grade on the final, hoping I’ll get it just how he wanted it.”), four had trouble making it to class, four reported personal/health issues (e.g., “I was homeless & in a clinical homeless emergency shelter/treatment center that did not have access to the internet and I was unable to leave the premises after a certain time.”), one complained about instructor bias, and another mentioned credit transfer issues.

Figure 1. Answers to the question “Finish the following sentence. Check all that apply. The last time I took this course, I...”

Wondering if the reasons for students dropping varied across different groups, I ran some cross-tabulations, finding that while 35% of students overall (as well as the Latinx subgroup) reported managing the workload as a major challenge, this jumped to 57% for those students who identified English as their second/additional language. Similarly, around 50% of students indicated they “Got behind,” a number that increased to 64% of Latinx and 71% of second language students. While around 50% of students indicated they “Couldn’t get excited,” a number that held for Latinx students, this dropped to 35% for L2 students, possibly because of their intrinsic motivation of learning an additional language to improve their educational and career prospects.

Overall, the survey findings reveal that students’ lives outside the classroom play an important role in their success, aligning with findings by Webb-Sunderhaus (“Life”) who profiled a struggling student, Roxie, who had a history of mental health and addiction issues and Ruecker, who reported that pregnancy and a lack of institutional and social supports for single student parents played an important role in interrupting his participants’ schooling. Given respondents’ concerns about the dryness of the curriculum or the inattentiveness of the professor, the scholars’ call for curricula that is more closely tied with students’ lives and interests merits further attention.

Interview Trends

During the analysis and coding of participant interviews, I identified three areas where writing program teachers and administrators could have the most impact in helping boost the success of students like those in this study: online courses, pedagogical and curricular choices, and program/institutional policies. I’ll explore these in the following sections.

Online Courses

The majority of interviewees (6 of 11) had previously struggled in online courses for various reasons, a finding that is reminiscent of Daniel in a previous study I conducted, a student who took multiple online classes his second semester but struggled when he did not have a “supportive teacher pushing him to do well” (52), fell further behind, and ultimately dropped out. Michael, a traditional-college-aged Latino, explained how the first time he took 102 he was surprised to find he had registered for an online class: “I did not exactly sign up for something like that that. I was thinking that it was going to be an actual classroom so I opted out to pretty much withdrawal from that and I knew I probably couldn’t pass a class like that.” He explained how it was harder to get motivated in a class without face-to-face accountability, a sentiment shared by Laura, a traditional-college-aged white female:

You have to very much be a self-starter and be self-motivated...and again, you’re missing that aspect of sort of accountability in person. It’s a lot harder to look teacher in the face and basically tell them, ‘I didn’t give a crap about your assignment or you or your class, so I didn’t do it’ than to just like have no interaction with the person.

As Laura indicates, it is easier to blow class and an instructor off virtually because, in her words, “it’s all online, so it doesn’t really exist.”

Michael did a nice job illustrating how a traditional writing class activity, peer review, may not transfer easily to an online environment:

The online course peer review was purely reading somebody’s work through online as in downloading...something they attached. Then on a discussion board on learn it was basically writing like a small paragraph on what did you think and so on and so forth. I felt very unmotivated to do this. It was something I could really care less about...[My F2F class is] a lot different than the of course online courses. I’m actually being able to interact with them and they can communicate back as I’m about to tell them one of my ideas for their paper, let’s say versus the online course was simply this is what I thought and here you are.

Online peer review can have some advantages, such as making students more comfortable in giving critical feedback to one another and in giving slower readers more time to read and comment on other students’ papers. Nonetheless, an important benefit of peer review is building classroom community, which as mentioned earlier, is an important part of promoting persistence (Astin). As Michael indicates by his comparison of online and face-to-face peer review, he experienced the latter as much more interactive and motivating than the online version, which was likely via an asynchronous discussion board.

Another aspect of promoting student persistence is that students feel cared for and recognized by their instructors—this sense of caring and recognition is conveyed in a face-to-face classroom in a variety of ways, including non-verbal interactions like eye contact and smiling and facial expressions of sympathy. In an online course, a sense of care is more directly tied to specific verbal exchanges and related actions. Here, Laura indicates a breakdown of communication and a perceived lack of care on her instructor’s part:

The course instructor wouldn’t return the feedback which, personally, like when I’m in English class, I wanna be able to see what my instructor says about my writing, and I wanna be able to improve upon that based on what the teacher said, and I wasn’t getting any of that back and she didn’t give very much instruction and so I think I ended up withdrawing from that class because I didn’t like the teaching style of it.

Laura was clearly frustrated by the inconsistency of communication and what appeared to her to be limited, inconsistent investment on her instructor’s part. Consequently, she withdrew because she did not see the value in continued investment on her end.

As I will explain in the recommendations section, online classes and activities in those classes can vary greatly, and a well-designed online class can go a long way in promoting student success; however, many learners are not well-suited to the greater independence of online learning.

Pedagogical and Curricular Choices

In both survey and interview responses, students expressed frustration with what they perceived as busy work or a lack of direction in their writing classes. David, an older Afro-Latino who had been attending school for a long time, found that conscious use of the program’s student learning outcomes (SLOs) helped focus instruction and understand where the class was heading:

This instructor has very clear objectives for us. I think she really utilizes the SLOs, I mean, really, really well. My last instructor didn’t do that, so it was unclear what he expected from us, and there was a lot of busy work that didn’t, in my opinion, aid to the bigger picture of obtaining those skills or putting them into practice.

It is evident in David’s response that the program’s focus on teaching towards specific SLOs and having students reflect on that progress helps mitigate some of the perceived aimlessness that causes some students to drop their writing classes. Writing from the two-year context, Joanne Giordano et al. describe the importance of professional development work in guiding instructors towards developing more focused, better scaffolded classes like the ones that benefited David, acknowledging that there are challenges to this work—a point I’ll return to later.

Falling behind was a common challenge reported by students in the survey. One way that SU’s writing program has addressed this is through careful scaffolding of assignments, which aligns nicely with the University’s mission focused on access and excellence—giving students the support to achieve ambitious goals. As Tanya, a traditional-college-aged female who did not identify with a specific race/ethnicity, explained:

I really enjoy this class. We have three major writing assignments throughout the semester and then our portfolio instead of a final and like each major writing assignment has three smaller writing assignments that we work on. It really helps to do all those smaller assignments because it makes me feel more prepared for the major writing assignment.

Here, Tanya describes what we hope to achieve when we carefully scaffold assignments in our classes—a step-by-step process that helps a student feeling overwhelmed with work and life both inside and outside school. In comparison, she said her previous class was “essay after essay after essay driving me crazy.”

With practices such as peer review and small group work, and also smaller class sizes compared to many other college classes on average, the writing classroom is an opportune place to foster community. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that not every student is looking for community. This was illustrated in detail by Kate, a white female in her mid-30s returning to college:

The component that I hate the most about 102 is that it’s so interactive. I’m like painfully antisocial and I just hated it you know the little group up and talk to your neighbor. I just, high school all over again I hated, hated it. So when I went the second round I thought we’ll go online and that’ll get rid of that. Not at all it’s almost worse you know, post to discussion boards and da da da I just hate it, hate it, hate it...

While Kate was the only participant who expressed such strong dislike for the community-building aspects of the classroom, writing program faculty can think about what they might do to accommodate someone like her who has such a strong aversion to group activities that led her to drop the class multiple times. It was also evident that age difference shaped her experience, as illustrated by this quote: “I walked in and some eighteen-year-old got very excited about my jeans and asked me what brand they were and it’s like sweetie I have no idea what kind of brand of jeans I wear.”

The types of writing students did shaped their overall engagement with the class, which is something revealed in the survey responses discussed earlier. In general, proponents of a more personal project to start out the first semester writing class argue that it provides a more accessible transition into college writing—writing that tends to be heavily research-based and impersonal, and ultimately different from much of what they previously experienced. Nonetheless, as Jonathan, a traditional-college-aged Native American male, explained, this strategy could backfire:

One of my problems was confidence issues with writing. I don’t feel like I was a very strong or good writer. And one of the things that immediately detracted me finishing was that all two or three [classes] that I had taken always required a memoir section which was usually right at the beginning and that’s usually where I would immediately stop.

As evident from this statement, Jonathan had repeated the class multiple times dropping when confronted with a personal assignment because he did not feel comfortable or interested in writing about his past. On the other hand, Laura found that the more personal focus her instructor followed in writing assignments engaged her and motivated her to succeed. Here she compared her previous and current courses:

The essay topics were very specific and sort of very much followed the very like standard I would say like English curriculum in terms of things like we spent a lot of time talking about rhetorical analysis and all of these different things, and then we were given like speeches to analyze, and we have to write our analyses up and sort of like the drier side of English whereas my English class this semester is, the teacher is a creative writing professor, so that’s where she’s approaching everything, so all of our assignments so far have been creative writing, um so she’ll like give us a prompt and say, “write about... an aspect of your identity, and then you can do sort of anything related to that.” And that I found to be a huge improvement for me because it makes it a lot easier to find something I’m passionate about.

The contradictory nature of these responses illustrates how not every assignment will please students and that it is important to think about how we can provide more options for students within assignments to avoid this like/dislike dichotomy. For instance, in the context of multimodal composition, Tiffany Bourelle et al. argue for giving students choices of the modality best suited for their project (e.g., a brochure, website, or video).

In general, students appreciated having a variety of assignments afforded by the genre-approach taken by the program. Tanya compared her previous and current classes:

She’s very, very specific with what she wants, which is normally a good thing because then you know exactly what criteria you need, but at the same time, hers was like so specific that she didn’t give us any wiggle room to be creative or have our own ideas. [In my current class we] look at all the different genres of writing really because that’s not something that I’ve ever been taught before is all the different like, different types of writing and how like each, like different types of writing have such a different feel and all that and I feel like this semester has really put that into my head. Making me not hate English or not like loath taking this class, you know.

Program and Institutional Policies

As discussed earlier, SU and the state legislature had recently instituted policies to push students to take 15 hours—for instance, students had to pass 15 credit hours each semester to keep the lottery scholarship, which paid for most tuition at any state school. Emily, a traditional-college-aged white female, described the complications and financial implications of such policies:

I make sure I have 18 credit hours so that if I drop a class, I still have 15, the 15 that’s required for my scholarship because I made that mistake my first semester, and I failed a class when I was taking 17 credit hours, and that dropped me to 14, and I was like, oh what do I do now? And so I had to take an intersession course to make sure I could keep my scholarship, which is like 500 dollars out of pocket to take that course.

Laura further illustrated the problems with a one-size-fits-all policy pushed by advocates who have pushed policies promoting 15 credit hours and graduation within four years as the norm:

I think I do better when I’m on 12 hours. Especially ‘cause I take a lots of studio art classes that take lots of time outside of class to complete projects and stuff like that, I feel like for me personally 12 hours is much more manageable. For me personally, it’s a struggle and then I don’t understand really how couldn’t it be a struggle for other people as well. And I also think it’s very different cause I was privileged in that I was living with my parents. I couldn’t imagine having to do that with knowing that I had to cover things like rent and food, and like if I had a family to support. It’s an immense amount of pressure on someone.

Referencing the lottery scholarship, Tanya vocalized the demoralization that many students face due to policies like the 15-hour requirement: “I feel like they made that specifically for you to lose.”

Writing programs typically have an attendance policy that varies by institution—the argument for this policy is that writing classes are smaller and involve a lot of peer work, so it is important that everyone is present to form a stronger community. At SU, instructors are typically told to drop students if they miss more than two weeks of class. As evident from the survey responses, some students ended up repeating the class because they became ill or had another outside challenge and were told to drop by the instructor. Laura illustrates how this policy led to her dropping the course:

I will also say honestly, my last teacher was much more strict about absences than my current teacher. I think she said six absences and then you’re out, and so even though I was turning in back work because she said I had missed too many classes she was kinda like, well, I can’t really pass you anyway, so I didn’t go to the rest of the semester. It’s like well if she’s not gonna pass me and I can’t drop it anyways, then there’s no point of me to continue to like to put my time into this class.

From Laura’s perspective, she seemed ready to catch up and finish the class, but the instructor felt constrained by the attendance policy and would not offer her an additional chance to finish the semester. Previous research has raised similar concerns with these attendance policies, with the Roxie in Webb-Sunderhaus’s study reporting that her grade suffered because of “attendance policies that institute a grade penalty when students miss more than the proscribed number of classes” (Life 124), even though those absences were due to illness or caring for her daughter. This issue speaks to the need to ensure instructors are aware of flexibility in these policies—a point I return to in the next section.

Recommendations for Writing Teachers and Administrators

As I often like to emphasize when discussing retention work with teachers in our writing program, students have complex lives outside the classroom and there is only so much we can do to ensure their success. Just as we often have little say regarding class sizes and workloads in our own institution, we have little control over social policies that fail to provide adequate healthcare or financial support so our students can focus their energies on their learning. Also, we may never please every student, as different students have difference preferences for instructional approaches—for instance, does it really make sense to change our collaborative pedagogies for the occasional student like Kate who may react negatively to these approaches? Nonetheless, I do believe there are steps we can take as instructors and program administrators to help promote student success in writing class, their overall engagement with the institution, and positively impact their likelihood of persistence towards graduation. Here are some ideas:

Building Classroom Communities

A strength of first-year writing classes is that they tend to be smaller than many classes across the institution, especially classes that students take as part of the general education curriculum in the first few years. Students tend to stick around if they have meaningful connections with students and faculty members, so building a sense of community in the classroom might make it harder for a student to disappear. It is evident from work like Jacob Babb and Steven J. Corbett’s that writing instructors care about their students’ success, with 53% of their instructor respondents reporting that they felt sadness when assigning failing grades.

There is a wealth of research in various fields on how instructors can connect with students, such as the “critical care” work out of education. Here, researchers have distinguished between “aesthetic” and “authentic” caring—the former limits caring to academic concerns while the latter “is grounded in a historical and political understanding of the circumstances and conditions faced by minority communities” and “translates race-conscious historical and ideological understandings and insights from counternarratives into authentic relationships, pedagogical practices, and institutional structures that benefit Latino/a students” (Rolón-Dow 104). As part of this authentic caring, it is vital that instructors reach out to students when they are missing, not restricting their message to concerns about maxing out attendance but inquiring to see how they are doing and what support can be provided. Similarly, providing students meaningful and timely feedback demonstrates how invested we are in their success.

However, these recommendations come with the caveat that teachers also need training and reasonable workloads to turn concern into action. Initiatives to truly support student success take time and upper-level administrators are often looking to increase teaching loads to save money in an era of declining budgets. Instructors teaching writing to a hundred students or more at one or multiple institutions likely have little opportunity or time to read the latest scholarship or attend professional development activities (Giordano et al.), so it is vital for administrators to advocate for professional development to be considered an important part of teaching loads and find resources for course releases to help provide individual instructors with more professional development opportunities. Program administrators also must continue to look for gaps where they can advocate for smaller class sizes. For instance, the upper administration at my current institution pushed to lower writing class sizes to 19 in order to improve the institution’s metric on various ranking systems that valued low student-to-teacher ratios. Because of the sheer number of classes in the writing program, lowering class sizes across our program made a big difference. By citing the benefit to metrics like Carnegie or U.S. News and World Report or documenting how small class sizes can have a positive impact on student retention rates, writing program administrators can advocate for smaller class sizes in a way that administrators will value.

One area where programs and instructors can have a positive impact without dramatically increasing workloads is with attendance policies. As found in this study and previous work (Ruecker; Webb-Sunderhaus Life), strict attendance policies often penalize students for reasons beyond their control, such as childcare demands or illnesses. In my experience, programs typically allow students to miss up to two weeks of classes without penalty—anything stricter than this should be considered highly problematic. But what if a student misses a month of class? I try to work with students as individuals, being cautious in failing them for missing a certain number of classes. Often, absences also mean that work is not being completed; however, if the student is continuing to complete most homework assignments and major assignments, then why arbitrarily mark them down for attendance? I’m reminded of Asao Inoue’s labor-based grading approaches in which he calls it racist that we judge students by a particular standard. Making attendance the sole factor in whether some students fail a writing course can be a similarly racist practice—by punishing students for lives that aren’t conducive to being in a particular place two or three days a week at a particular time, we often penalize students of color or students from lower socioeconomic classes who miss the bus, can’t afford childcare, or have a schedule change at work. While we can encourage them to explore online options, it is important to recognize that online courses may also fail students who would benefit from in-person contact with a classroom community.

Mindful Design for Online Courses

As institutions increasingly develop online education options and since we have become more comfortable with online education in the COVID-19 era, it is clear that writing classes will be increasingly offered online. While this shift is beneficial for many students who have trouble attending a traditional class, it is evident that an online course is not the right choice for many students, as previous research has found lower success rates in online classes, especially among students from minoritized backgrounds (Johnson and Mejia). Students in this study were not always aware of signing up for an online class nor knew exactly how it would compare to a F2F classroom (e.g., when Michael said “I did not exactly sign up for something like that that.”). To that end, writing programs should make sure students are given information in advance about the structure of their online courses and make sure they are clearly defined in the registration system—they can work with student advisors to make sure students are given this information as well.

Along these lines, programs might develop a guided self-placement survey such as the one discussed by Sara Webb-Sunderhaus and Stevens Amidon, with questions more closely aligned with online learning. These can include how well students work independently or how important face-to-face conversations are in their learning. It is evident that some students missed the community feeling of F2F classrooms, whether the more robust peer review experience (Michael) or the accountability by seeing their instructor in person (Laura). As Webb-Sunderhaus and Amidon and others note, establishing a DSP approach requires activism on multiple fronts—changing attitudes among administrators and advisors, finding funding to support the approach, and working within any constraints faced by public institutions, which are often required to follow state-wide placement policies. However, establishing an advisory DSP system for online versus F2F placements may be less constrained by the latter than a system that places students in a particular level of writing since students usually have the choice to enroll in an online or F2F section—advisors could discuss the survey results with advisees as they weigh their decision-making process.

Either way, it is vital for online writing programs and instructors to think about ways to bring some of the classroom community feeling online, such as having students form discussion groups rather than having one set of discussion threads for the whole class. Working during the COVID-19 pandemic has raised the distinction between online and remote classes, the latter incorporating synchronous components. Along these lines, students who cannot take a F2F class for whatever reason but would prefer to have some synchronous interaction could enroll in a remote rather than a purely online asynchronous course. This gives instructors options for more engaging and real-time interaction that moves beyond the overused “post to this discussion thread and respond to two peers” assignment. In another vein, Gaytan found that increased faculty instruction and meaningful feedback were most-commonly mentioned among online students as supporting retention—consequently, clear guidance from instructors as well as a regular presence via thoughtful feedback is important.

The community of inquiry (COI) framework developed by D. Randy Garrison et al. is a useful heuristic for designing online courses—it focuses on improving social, cognitive, and teaching presences. According to the authors, cognitive presence is the basis for success in higher education and refers to the students’ and teachers’ abilities to construct knowledge through ongoing communication. Social presence refers to the ability of both students and instructors to represent themselves as “real people” in the online class environment. Teaching presence consists of two components: the design of the learning experience (e.g., course content and the design of learning activities) and the ongoing facilitation of the learning experience. Mary K. Stewart used COI as a heuristic to develop more interactive online activities in an online FYW course, emphasizing that interactive learning is possible in both media lean and media rich environments and depends on careful instructional design. For instance, her focal student, Nirmala, reported that of three activities—an online asynchronous discussion, a co-authored Google document, and a synchronous video webinar—the asynchronous discussion was the only activity that the student deemed successful. Using the COI framework, Stewart explains why:

There was a clear cognitive goal: [the instructor] wanted her students to build upon their classmates’ ideas to support their own understanding of the topic, which they would present in their argumentative essays. Cognitive presence was further established because the activity required students to grapple with an issue that did not have one clear solution. The teaching presence of the activity directly supported that cognitive presence: the prompt solicited multiple perspectives, and the requirement to respond to a peer who answered a different question than the one the student answered encouraged student engagement with diverse viewpoints. (73-4)

It is evident that well-designed activities that promote social, cognitive, and teaching presences in the online writing classroom can go a long way in promoting student engagement and success.

Student-Responsive Curriculum

As evidenced by the different responses to personal writing that Jonathan and Laura had, not every assignment is going to please everyone. While we certainly cannot please every student who moves through our classes, students like Jonathan and Laura should have choices within assignments as the aforementioned Bourelle et al. discussed in terms of modality choices. For instance, for a more personal project like a literacy narrative, students like Jonathan may not feel comfortable or interested in writing about themselves; instructors might give students like this the flexibility to choose the subject of their assignment, instead writing a profile of an important person in their life.

Writing programs are typically populated with teachers from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds, especially English literature, creative writing, and rhetoric and writing. While reading works within one’s research specialty may be exciting for the instructor, I go back to that survey response which harshly condemned such an approach: “We read very old American History-esque, overrated books and their matching movie lucky enough to be produced by someone who really gave a damn about Huckleberry Finn etc. back in the 50s.” Whether because of instructor disciplinary background or other reasons, it is evident that the curriculum at diverse institutions like SU often fails to reflect the diversity of the students. Research has shown that curriculum that respects students’ languages and cultures has been shown to promote higher grades, retention, and graduation rates (Cabrera et al.). It is important that writing teachers and administrators continue to expand the use of culturally responsive curricula and document how this work contributes to student success, as this will be a vital component in defending these curricular choices against misinformed administrators, faculty in other disciplines, or members of the public.

Another consideration of diversity that arose in talking with Kate, who was a returning student in her mid-30s, was the idea of having writing classes for older/returning students:

Todd: So do you think it would be productive to have like a I don’t know like a class designated maybe for late starters or

Kate: I think that would be fabulous.

Todd: Like in their 30s or something

Kate: Yeah cause I found that we all kinda relate. You sorta find each other like on the online version at least in discussion boards and stuff your kinda like oh thank God someone else that’s not 18 you know.

A course filled with older learners and taught by an older instructor has the potential to create bonds between students and their instructors that can facilitate the success of a student like Kate, who struggled to connect with the young first-year students populating the classes she had dropped out of previously. Readings and discussion topics could also be more specifically tailored for this audience who might already have years of experience writing for various professional purposes that they can draw and build on as they translate these skills for academia.

Concluding Thoughts

It is evident from the results of this study and our own experiences as administrators and teachers that we cannot guarantee the success of all students that pass through our classes. Students often drop or fail our class for reasons that we have little control over: they or a family member gets sick, they do not have access to adequate housing, or have unmet financial obligations that force them to work or drop out of college. However, something I have tried to emphasize here is that there are many steps in our programs and classes that we can take to support students who struggle. By thinking carefully about our program policies and our curricular and pedagogical decisions and advocating for change, we can help some of the students who would otherwise fall behind or feel unmotivated to come to class to complete their work and pass. This can make a huge difference in students’ lives, as failing one class can have disastrous long-term impacts on a student’s possibility to succeed—Garrett et al. found that students at their institution who fail a writing class twice have only a 6% chance of graduation (104).

Unfortunately, as discussed at the beginning of this article, writing teachers and administrators often have little control over policies set at the national, state, or institutional level that take a narrow view of what makes a successful student: one who lives and works on campus, graduates within four years, comes from a middle or upper-class family, and does not have outside family or work obligations. These policies are too often designed to promote an institution’s retention and graduate rates with the lowest monetary investment possible—we never see the same enthusiasm for reducing class sizes and workloads and providing childcare as we do for policies that push a working parent to take 15 credit hours to keep their scholarship. Nonetheless, we do have a lot of control over what happens in our programs and classrooms. Beyond that, I find inspiration in the work of Linda Adler-Kassner who has long made the case for an activist WPA: “If we have a chance to make our case, then make it we must.” (136).

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Heidi Estrem, Dawn Shepherd, and Beth Brunk-Chavez for their help in designing this study with an additional shout out to Beth for giving feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. I would also like to thank Greg and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback and for understanding the importance of this work.

Notes

-

All institutional and student names in this article are pseudonyms. (Return to text.)

-

Any grade below a C is considered failing—my analysis of a separate dataset found that around 11% of 101 students on SU’s main campus typically receive a C- or below or withdrawal. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda. The Companies We Keep or the Companies We Would Like to Try to Keep: Strategies and Tactics in Challenging Times. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 36, no. 1, 2012, pp. 119-40.

Astin, Alexander W. What Matters in College?: Four Critical Years Revisited. Jossey-Bass, 1997.

Babb, J. and Steven J. Corbett. From Zero to Sixty: A Survey of College Writing Teachers’ Grading Practices and the Affect of Failed Performance. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016. http://compositionforum.com/issue/34/zero-sixty.php.

Bourelle, Tiffany, Angela Clark-Oates, and Andrew Bourelle. Designing Online Writing Classes to Promote Multimodal Literacies: Five Practices for Course Design. Communication Design Quarterly Review, vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, pp. 80-88.

Cabrera, Alberto F., Stampen, Jacob O., and Hansen, W. Lee. Exploring the Effects of Ability to Pay on Persistence in College. The Review of Higher Education, vol. 13, no. 3, 1990, pp. 303-336.

Cabrera, Nolan L., Jeffrey F. Milem, Ozan Jaquette, and Ronald W. Marx (2014). Missing the (Student Achievement) Forest for All the (Political) Trees: Empiricism and the Mexican American Studies Controversy in Tucson. American Educational Research Journal, vol. 51, no. 6, 2014, pp. 1084-1118.

Chemishanova, Polina and Robin Snead. Reconfiguring the Writing Studio Model: examining the Impact of the PlusOne Program on Student Performance and Retention. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Programs, edited by Todd Ruecker, Dawn Shepherd, Heidi Estrem, and Beth Brunk-Chavez. UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 167-184.

Complete College America. Homepage. https://completecollege.org.

Day, Michael, Tawanda Gipson, and Christopher P. Parker. Undergraduate Mentors as Agents of engagement: Peer Advocates in First-Year Writing Courses. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Programs, edited by Todd Ruecker, Dawn Shepherd, Heidi Estrem, and Beth Brunk-Chavez. UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 237-256.

DeAngelo, Linda, Ray Franke, Sylvia Hurtado, John H. Pryor, and Serge Tran. Completing College: Assessing Graduation Rates at Four-Year Institutions. Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA, 2011.

Garrett, Nathan, Matthew Bridgewater, and Bruce Feinstein. How Student Performance in First-Year Composition Predicts Retention and Overall Student Success. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Programs, edited by Todd Ruecker, Dawn Shepherd, Heidi Estrem, and Beth Brunk-Chavez. UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 93-113.

Garrison, D. Randy, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer. Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, vol. 2, nos. 2-3, 1999, pp. 87-105.

Gaytan, Jorge. Comparing Faculty and Student Perceptions Regarding Factors That Affect Student Retention in Online Education. American Journal of Distance Education, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 56-66.

Giordano, Joanne, Holly Hassel, Jennifer Heinert, and Cassandra Phillips. The Imperative of Pedagogical and Professional Development to Support the Retention of Underprepared Students at Open-Access Institutions. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Programs, edited by Todd Ruecker, Dawn Shepherd, Heidi Estrem, and Beth Brunk-Chavez. UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 74-92.

Glau, Gregory R. ‘Stretch’ at 10: A Progress Report on Arizona State University’s Stretch Program. Journal of Basic Writing, vol. 26, no. 2, 2007, pp. 32-50.

Inoue, Asao B. Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. WAC Clearinghouse, 2019.

Jaschik, Scott. The Questions Developed to Cull Students. Inside Higher Ed, 26 Feb. 2016, https://insidehighered.com/news/2016/02/12/questions-raised-about-survey-mount-st-marys-gave-freshmen-identify-possible-risk. Accessed 23 June 2020.

Johnson, R. Burke and Larry Christensen. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches. Sage. 6th edition, 2016.

Johnson, Hans P. and Marisol Cuellar Mejia. Online Learning and Student Outcomes in California’s Community Colleges. Public Policy Institute of California, 2014.

Malenczyk, Rita. Retention Panopticon: What WPAs Should Bring to the Table in Discussions of Student Success. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Programs, edited by Todd Ruecker, Dawn Shepherd, Heidi Estrem, and Beth Brunk-Chavez. UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 21-37.

Powell, Pegeen Reichert. Absolute Hospitality in the Writing Program. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Programs, edited by Todd Ruecker, Dawn Shepherd, Heidi Estrem, and Beth Brunk-Chavez. UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 135-150.

---. Retention and Resistance: Writing Instruction and Students who Leave. Utah State University Press, 2014.

Rendón, Laura I., Jalomo, Romero E., & Nora, Amaury. Theoretical Considerations in the Study of Minority Student Retention in Higher Education. Reworking the Student Departure Puzzle, edited by John M. Braxton, Vanderbilt University Press, 2000, pp. 127-56.

Rolón-Dow, Rosalie. Critical Care: A Color (full) Analysis of Care Narratives in the Schooling Experiences of Puerto Rican Girls. American Educational Research Journal, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 77-111.

Ruecker, Todd, Dawn Shepherd, Heidi Estrem, and Beth Brunk-Chavez, editors. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Instruction. Utah State University Press, 2017.

Ruecker, Todd. Transiciones: Pathways of Latinas and Latinos Writing in High School and College. Utah State University Press, 2015.

Stewart, Mary K. Communities of Inquiry: A Heuristic for Designing and Assessing Interactive Learning Activities in Technology-Mediated FYC. Computers and Composition, vol. 45, 2017, pp. 67-84.

Tinto, Vincent. Dropout from Higher Education: A Theoretical Synthesis of Recent Research. Review of Educational Research, no. 45, vol. 1, 1975, pp. 89-125.

Snyder, Sara Elizabeth. Retention Rates of Second Language Writers and Basic Writers: A Comparison within the Stretch Program Model. Ruecker et al., pp. 185-203.

Webb-Sunderhaus, Sara. ‘Life Gets in the Way’: The Case of a Seventh-Year Senior. Retention, Persistence, and Writing Programs, edited by Todd Ruecker, Dawn Shepherd, Heidi Estrem, and Beth Brunk-Chavez. UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 114-134.

---. When Access Is Not Enough: Retaining Basic Writers at an Open-Admission University. Journal of Basic Writing, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 97-116.

Webb-Sunderhaus, Sara and Stevens Amidon. The Kairotic Moment: Pragmatic Revision of Basic Writing Instruction at Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne. Composition Forum, vol. 23, 2011. http://compositionforum.com/issue/23/ipfw-revision.php.

Wolf-Wendel, Lisa, Kelly Ward, and Jillian Kinzie. A Tangled Web of Terms: The Overlap and Unique Contribution of Involvement, Engagement, and Integration to Understanding College Student Success. Journal of College Student Development, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 407-428.

Zawacki, Terry Meyers and Ashley Taliaferro Williams. Is It Still WAC? Writing within Interdisciplinary Learning Communities. WAC for the New Millennium: Strategies for Continuing Writing-Across-the-Curriculum Programs, edited by Susan H. McLeod, Eric Miraglia, Margot Soven, and Christopher Thaiss, NCTE, 2001, pp. 109-140.

Retention and Persistence in Writing Programs from Composition Forum 46 (Spring 2021)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/46/retention.php

© Copyright 2021 Todd Ruecker.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 46 table of contents.