Composition Forum 38, Spring 2018

http://compositionforum.com/issue/38/

Teaching and Learning Threshold Concepts in a Writing Major: Liminality, Dispositions, and Program Design

Abstract: In this article, we discuss what it means to learn troublesome “threshold concepts” about writing that cannot be adequately grappled with in a single course or assignment. Here, two faculty members and a graduate of a writing major reflect on elements of the writing curriculum, the writing center practicum, and the learning dispositions and experiences the student brought to the program in order to consider what ongoing, deep learning of writing threshold concepts can look like, as well as how programmatic and pedagogical elements may afford and constrain such learning.

A great deal has been written about how learning works (Tagg; Ambrose et al.) and about threshold concepts in general and in many disciplines (Burkhardt; Clark; Hamilton; Launius and Hassel; Land, Meyer, and Flanagan; Land, Meyer, and Smith; Meyer, Land, and Baillie; Hofer, Hanick, and Townsend). We know very little about what it looks like for students to grapple with threshold concepts in Writing Studies, however. Linda Adler-Kassner, John Majewski, and Damien Koshnick have explored the learning of threshold concepts in a general education writing course (as well as a history course). Elizabeth Wardle and Doug Downs have organized the second and third editions of their composition textbook, Writing about Writing, around writing threshold concepts. The 2015 book Naming What We Know outlined some threshold concepts for the field of Writing Studies, and explored how writing curricula at different levels might be designed around threshold concepts (Downs and Robertson; Scott and Wardle; Taczak and Yancey). However, there is little research about how students engage with and learn writing threshold concepts. That is the gap that this reflective analysis seeks to address. In it, Mikael, one of the authors of this article, recounts his experiences encountering several threshold concepts about writing during his time completing a B.A. in writing and rhetoric. Mikael and two of his former faculty members, Elizabeth and Mark, reflect on his experiences in order to consider the complex ways that learning about writing happens across time. Here we look at two threshold concepts identified by Mikael that were both difficult and transformational for his thinking and practices as a writer and writing center peer tutor: “Assessing writing shapes contexts and instruction” and “Writing involves the negotiation of language differences.” Mikael identifies coursework in the writing major and its interaction with his experiences in the writing center as working together across time to mutually reinforce his learning of writing-related threshold concepts and to keep him engaged in an uncomfortable liminal space. We conclude that some elements of the writing major and writing center practicum that Mikael encountered together offered him a set of what the Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) calls “high impact” experiences (Kuh) that served as a catalyst for deep learning (including internships, a capstone course, and undergraduate research). However, we also recognize that program design is only part of the story. Mikael, an oldest child of three and immigrant from Ecuador, came to college and to the writing major with particular experiences and learning dispositions that inclined him to persist in the face of challenges and to be open to problem-based learning and exploration. We ask how programs can effectively reach students who do not initially appear to inhabit the same learning dispositions.

To tell this story, we begin with background on threshold concepts—concepts that are critical for epistemological participation in a discipline—and then outline some ways that the learning of threshold concepts is influenced by the learner’s dispositions and sense of self. We then apply this framework to Mikael’s experiences as a learner, both prior to and during his time in the writing major, and explore a set of threshold concepts with which he struggled. We conclude by summarizing some of the factors that enabled Mikael to work through troublesome threshold concepts and ask how writing faculty members can extrapolate from those experiences as they work to help other students engage in the same kind of deep learning. This reflective case analysis contributes to discussions regarding how the curricula of writing majors can afford or constrain deep learning and what this might require of faculty in terms of course and assignment design as well as collaboration across courses. It also highlights the importance of dispositions and learners’ own sense of who they are—and asks faculty to consider how to bring these to conscious awareness in classrooms. Finally, our analysis contributes to the growing body of work written with students, rather than about them.

Threshold Concepts

Threshold concepts are concepts critical for epistemological participation in a discipline. The lens of threshold concepts was first described by Jan Meyer and Ray Land, as part of a “UK national research project into the possible characteristics of strong teaching and learning environments in the disciplines for undergraduate education” (Cousin). Learners need to use them as lenses for analysis and interpretation within different disciplines. Meyer and Land have outlined several defining characteristics of threshold concepts. They are:

-

Liminal: They serve as “portals” to new and different ways of experiencing, but learners’ movement toward these portals may be neither contiguous nor smooth. Learning entails “recursiveness...and...oscillation.”

-

Troublesome: They are often conceptually difficult and may conflict with common conceptions of a subject. Thus, prior knowledge may impede learning of threshold concepts. Because deep learning of these concepts requires embodiment and a shift in discourse, learning them may also be troublesome because doing so requires an identity shift, a “change a learner may not wish to embrace.”

-

Integrative: Through threshold concepts, learners perceive connections between concepts and ideas.

-

Likely irreversible: While they are troublesome to learn, once learned, learners find it difficult to see the world as they did prior to crossing the threshold. (Land, Cousin, Meyer, and Davies x-xi).

Threshold concepts are often some of the underlying assumptions and knowledge of a discipline. Disciplinary experts may see them as obvious because they mastered them deeply and often long ago. Thus, they constitute insider knowledge that may sometimes be left unstated (or not stated frequently enough) in instruction. Meyer and Land’s concern in theorizing threshold concepts is, in part, to help experts re-see their threshold concepts in order to teach them more effectively to newcomers.

Threshold concepts are different from “core” or “key” concepts in their capacity to transform the learner. They are “superordinate ... relate previously disparate ideas and ... give students a broader view of the subject” (Biggs and Tang 84). A core concept, on the other hand, is a conceptual “building block that progresses understanding of the subject; it has to be understood but it does not necessarily lead to a qualitatively different view of the subject matter” (Meyer and Land 6). It “do[es] not lead to a dramatic shift to a new level of understanding” (Biggs and Tang 83). For example, take the threshold concept “writing enacts and creates identities and ideologies” outlined by Tony Scott in Naming What We Know. There are at least two core or key concepts that learners need to understand before they can engage in the transformational shift in view that this threshold concept suggests: “identities” and “ideologies” (“writing,” at least as our field defines it, could also be a core concept). In fact, Scott begins his description of this threshold concept by defining ideology. Understanding the key terms is necessary but not sufficient for grasping the larger threshold concept. That threshold concept, once understood and enacted, has consequence, as Scott explains, for how learners understand and engage in public discourse and in “the structures and practices that continue to prevail in many educational institutions,” including “[r]equired writing courses and gatekeeping assessments” such as “first-year writing and placement tests” (49). Core or key concepts are much easier to teach and assess than threshold concepts; students can be asked to define terms like “ideology.” While threshold concepts can be explained and taught and perhaps even regurgitated back by learners, when and how (or whether) learners integrate and embody (enact) them in their practices and orientations differs for myriad reasons, and are thus much harder to assess—likely impossible to assess with efficient, short-term, pre/post measures.

Liminality is the hallmark of learning threshold concepts. Richard Rohr explains: “‘Limina’ is the Latin word for threshold, the space betwixt and between ... It is when you have left the ‘tried and true’ but have not yet been able to replace it with anything else ... It is when you are in between your old comfort zone and any possible new answer. It is no fun” (np). Uncertainty is discomforting; therefore, a central challenge for faculty is to assist students in managing the discomfort and provide scaffolding to help them remain in the liminal space and continue to navigate through it.

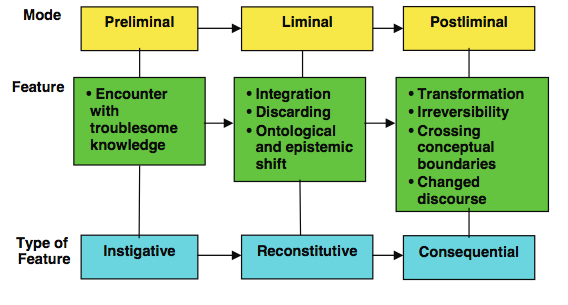

Meyer, Land, and Baillie have outlined three (nonlinear) stages of learning related to liminality (see Figure 1). In the preliminal stage, learners are confronted with the troublesome knowledge of a threshold concept. This encounter can instigate learning, or the learner can choose not to engage the concept. The second stage is liminality. Learners can stay “in a state of ‘liminality’, a suspended state of partial understanding, or ‘stuck place’, in which understanding approximates to a kind of ‘mimicry’ or lack of authenticity” (Land, et al. x). In this stage, learners must integrate what they already know with what they are learning, discard what doesn’t work, and engage in both ontological and epistemological shifts—shifts in both being and knowing. Theorists such as Julie Timmermans, Glynis Cousin, and Vernon Trafford have compared the relationship of this stage to Vygotsky’s “zone of proximal development” (ZPD) (86), noting affinities between the metaphors of the ZPD and liminality: “each metaphor invites a view of learners who go through journeys that involve insecure, transitional states before mastery,” although there are differences in each perspective pertaining to a “transfiguration of identity” versus “increased mastery” (Cousin 265). When and how each learner moves through the liminal space depends on a host of factors beyond cognitive ability, which are only beginning to be understood.

If learners succeed in moving through the liminal space, then they move into a postliminal stage that is marked by a shift in discourse. The learner begins to sound like experts in that discipline and begins to see connections where there were none previously. That is not to say that post-liminality is pleasant and problem-free. Seeing connections allows for new problems and questions to come into focus, but seeing such problems and questions is exactly what allows the learner to continue progressing in (and begin making contributions to) the field; it likely also results in repeated engagements with liminality.

Figure 1. A relational view of the features of threshold concepts (Meyer, Land, and Baille)

Learning threshold concepts, then, necessarily involves deep learning, changing how we think. What does “deep learning” mean? John Tagg offers a definition in The Learning Paradigm College. Deep learning, he argues, depends upon multiple processes: focusing on making meaning, actively constructing knowledge, relating new knowledge to prior knowledge, integrating knowledge into “semantic memory,” relating new knowledge to broader theoretical ideas, being mindful, and making learning enjoyable (81).

In Mikael’s experiences, described later in this article, we will discuss his encounters with threshold concepts, the factors that afforded and constrained his ability to engage in deep learning, and the supports and scaffolding that enabled him to move through the discomfort of liminality.

Dispositions and Identity Formation

Whether, how, and when learners like Mikael move through liminal spaces is dependent on a host of factors beyond cognitive support and curricular scaffolding. One factor that appears to have an influence is a person’s disposition for learning. Dispositions help account for patterns of behavior that determine people’s use of cognitive skills. David Perkins, Eileen Jay, and Shari Tishman define dispositions as “tendencies toward patterns of intellectual activity that condition and guide cognitive behavior” (6). Dispositions are acquired over time in response to home, school, and varied cultural experiences and contexts. A set of dispositions form what Pierre Bourdieu calls habitus, “which incline agents to act and react in certain ways. The dispositions generate practices, perceptions, and attitudes which are ‘regular’ without being consciously co-ordinated or governed by any ‘rule.’ The dispositions which constitute the habitus are inculcated, structured, durable, generative, and transposable” (Thompson 12). Sets of dispositions, once acquired, seem to be difficult to change.

Inquiries in the fields of psychology and general education outline distinctions between cognitive skills and dispositions, with implications for how instructors engage students in critical thinking (Giancarlo and Facione). In Writing Studies, Dana Driscoll and Jennifer Wells (among others) explore the role that some dispositions play in the transfer of writing-related knowledge. Perkins et al. list what they describe as seven thinking dispositions conducive to productive intellectual behavior:

-

The disposition to be broad and adventurous: open-minded; explore alternative views; being alert to narrow thinking; the ability to generate multiple options.

-

The disposition toward sustained intellectual curiosity: to wonder, probe, find problems, observe closely and formulate questions; a zest for inquiry, alertness for anomalies.

-

The disposition to clarify and seek understanding: a desire to understand clearly, to seek connections and explanations; an alertness to muddiness, an appreciation of the need for focus; an ability to build conceptualizations.

-

The disposition to be “planful” and strategic: the drive and ability to set goals, make and execute plans, envision outcomes; an alertness to a lack of direction.

-

The disposition to be intellectually careful: the urge for precision, organization, thoroughness; an alertness to possible error or inaccuracy; the ability to process information precisely.

-

The disposition to seek and evaluate reasons: the tendency to question the given, to demand justification; an alertness to the need for evidence; the ability to weigh and assess reasons.

-

The disposition to be metacognitive: the tendency to be aware of and monitor the flow of one’s own thinking situations; ability to exercise control of mental processes and to be reflective. (7-8)

In Writing Studies, Elizabeth Wardle has similarly explored how learners approach problems. She posits that a learner’s approach to intellectual problems (and, for our purposes here, their willingness to engage with the “troublesomeness” of threshold concepts) has a significant impact on their ability to do the work: “‘Problem-exploring dispositions’ incline a person toward curiosity, reflection, consideration of multiple possibilities, a willingness to engage in a recursive process of trial and error, and toward a recognition that more than one solution can ‘work.’ ‘Answer-getting dispositions’ seek right answers quickly and are averse to open consideration of multiple possibilities” (np).

While the dispositions that students acquire and inhabit across time can account for some of the reasons why some learners succeed in their encounters with threshold concepts while others do not, dispositions alone cannot fully explain why, when, and how one group of students moves through liminality while others remain “stuck.” Successful movement also seems to depend on identity and sense of self, in relation to the particular threshold concepts encountered. As Land, Meyer, and Baillie remind us, “Being and knowing are inextricably linked. We are what we know, and we become what we learn ... an act of learning is an act of identity formation” (xxviii). Deep learning of threshold concepts is an act of identity formation, reformation, and ongoing formation. Etienne Wenger calls such learning the “work of reconciliation” and notes that it involves “constructing an identity that can include ... different meanings and forms of participation into one nexus.” He is careful to point out that “the process [of reconciliation] is never done once and for all... . Proceeding with life ... entails finding ways to make our various forms of membership coexist” (160-1). Proceeding with the learning of threshold concepts in a particular discipline entails finding ways to make membership in that discipline and embodiment of that discipline’s threshold concepts align (or at least coexist with) the learner’s membership in other communities of practice. Although Wenger is not specifically describing encounters with threshold concepts, the work of reconciliation and identity formation and reformation he describes do seem, in some ways, to loosely map onto the stages of and experiences with liminality that Meyer, Land, and Baille outlined in the earlier chart, as Cousin points out (“Threshold Concepts: Old Wine”).

As we mentioned at the outset, this article seeks to explore what it looks like for students to engage in this kind of liminal learning in regard to threshold concepts of Writing Studies, something we currently know very little about. In describing Mikael’s experiences, we ask:

-

How are writing-related threshold concepts encountered and experienced by a student?

-

What does it look like when a student successfully moves through liminal spaces around writing?

-

What programmatic and pedagogical elements afford and constrain students in this movement through liminality?

-

What role do dispositions play in this movement?

-

What role does time—and engagement across time—play in helping students move through liminality and grappling with threshold concepts?

Other disciplines have explored similar questions (see Burkhardt; Clark; Hamilton; Launius and Hassel; Land, Meyer, and Flanagan; Land, Meyer, and Smith; Meyer, Land, and Baillie; Hofer, Hanick, and Townsend), but writing scholars are only beginning to think about them. To begin to explore these questions, we offer this reflective analysis, written with, by, and about one student who successfully completed a B.A. in writing and rhetoric in a program that was somewhat deliberately designed around threshold concepts.

Method of Conducting the Reflective Analysis

Elizabeth and Mark did not set out to conduct a study of how students learn threshold concepts, but were engaging in our usual work of teaching and program administration when this project came to be. Elizabeth taught a pilot version of a capstone course for Writing and Rhetoric majors in which Mikael was enrolled. This capstone course explicitly asked students to consider the threshold concepts they had encountered during their time in the major. All the students in the class struggled in various ways with threshold concepts, but Mikael seemed to have moved through the liminal space into the postliminal space on several of them (which many of the other students had not), and was able to articulate his struggles with those concepts in ways that some of his peers could not yet do. At the end of the class, Elizabeth asked him if he would like to continue exploring his engagement with threshold concepts by writing an article together about his experiences. He agreed, and suggested they also invite Mark, the Writing Center Director, because Mikael’s experiences in the center had deeply impacted his ability to move through the liminal space on some of the most difficult threshold concepts, a fact he mentioned repeatedly in his writing throughout the capstone course. The three of us met during the final semester of Mikael’s senior year to talk about what such an article might look like, and we continued to meet, write, and reflect for more than a year after his graduation.

Our group examined Mikael’s reflective writing and analysis from the capstone course, and he served as a guide in those conversations. He also returned to all of the writing he had composed throughout the major—a reflective project he had begun in the capstone course—and shared with us what he felt was important and worth discussing further. Our work together is not, then, a traditional research project. Rather, it entails a collaborative retrospective of one former student’s experiences, and aspects of the curricular choices designed by faculty that the student himself determined to be more and less central in affording his learning. This collaborative reflection and analysis treats Mikael as an expert on his own experiences, and relies on his reflections and analyses to help us answer questions like: what does deep learning of writing look like? What learning practices and opportunities aid students as they engage in learning of difficult threshold concepts about writing? What are seminal dispositions and aptitudes that students bring with them to our curricular designs? How are students supported (or not) as they struggle in liminal spaces?

Of course, we recognize the limitations of such an approach. We did not set out to assess or measure the learning of all students in the writing and rhetoric major. We have not collected data about other students for whom the coursework and practicum experiences were or were not effective. We cannot generalize from the experiences of one successful student. We offer Mikael’s experience as a beginning: we urge others to continue the work of asking students themselves what affords and constrains their learning of writing-related threshold concepts and to use that information to design and revise experiences that encourage deep learning across liminal spaces.

Not only do we take to heart Peter Felten’s admonition that we “[invite] students to partner with us in our research and practice” about threshold concepts (7), but we also recognize here that Mikael’s voice, reflection, and experience—narrative in nature as they are—are what enable any insight at all into what it is like for a student to struggle in and then move through liminal spaces. In order to underscore the centrality of Mikael’s experience and authority over that experience, the sections written by him and about his experiences in this article are in first person, in his own words.

Mikael’s Encounter With Several Threshold Concepts

We begin at the end of Mikael’s education, by demonstrating what it sounded like for him to talk about several threshold concepts from a post-liminal space as a graduating senior. After he describes these concepts from his perspective, we will go backward—to identify aspects of Mikael’s dispositions/experiences, writing center work, and the writing curriculum that assisted him in learning these concepts. There are a number of threshold concepts that Mikael could discuss here, but what follows is his reflection on two he considered particularly difficult but important learning challenges. What follows is a slightly revised version of the language he used in an assignment for the capstone course, where he first identified threshold concepts in Naming What We Know that were particularly significant to him and then reflected on experiences that enabled his understanding. Although his understanding has continued to develop since (particularly because he has held a full-time position as a professional writing center tutor at a nearby state college since he graduated), we want to illustrate not what he knows now but rather what it looked like for him as a graduating senior to comment on several writing-related threshold concepts.

Mikael’s

Reflection on Two Threshold Concepts:

“Assessing

Writing Shapes Contexts and Instruction”

“Writing

Involves the Negotiation of Language Differences”

I worked as a writing center tutor for about a year and a half, or a total of five semesters, while also taking courses in the writing and rhetoric major. One outcome of studying writing and rhetoric while tutoring writing is that I got the chance to develop a disciplinary identity. Part of the core of my personal tutoring philosophy is the knowledge that my assessment of writing is derived from a set of standards which aren’t solely my own; ergo, as a Writing Center tutor, part of the job is judging other people’s writing through the lenses of institutional and disciplinary values. While tutor education did not explicitly encourage us to “judge” student writing, tutors can't help but judge to some degree. This is something I didn't fully understand until I had been tutoring and reflecting on it for some time. Over time, I developed a heightened awareness of how tutoring is a form of assessment that may affect many students’ learning of college writing.

Indeed, Tony Scott and Asao Inoue (Adler-Kassner and Wardle 29-31) observe that assessing writing shapes the contexts and instruction in which it occurs. To tutor students in a Writing Center context is to scaffold their progress through college writing. However, assessment in the Writing Center also means that tutors like me enact standards which guide how writing should be carried out. Put another way, tutoring is a form of assessment. To the extent a consultation allows, my role affects what students think about college, how they approach their courses, and, if I tutor a student long enough, our interactions have the capacity to affect how they think in order to write. I can say this with confidence because I’ve gone through enough consultations to observe that although my role as tutor ends when the session is over, what I did in that role has the potential to linger with the student.

One of the most common ways my role has served to shape the learning context at the University of Central Florida was when I tutored first-year students, helping them to acclimate to the academic writing expected in first-year composition. Many first-year students enter college with preconceptions of what writing is about, but some of those very conceptions render them capable of misrepresenting the goals of college writing. Often, student writers express high regard for grammatical correctness and formulaic paragraph constructions, but in doing so, they may neglect to value the global aspects of writing. My role as a tutor is to help them break out of unhelpful writing practices. For example, several tutors and I worked with a group of first-year students in a summer bridge program. Writing Center tutors served as mentors, not only to help them with writing but also to ease the transition from high school to college. My role as a mentor was to get them to talk amongst themselves about their writing, whereupon they would often say that they didn’t understand the assignment instructions. Additionally, my role would have me clarify assignments where I could and to help them to figure out next steps, sometimes redirecting writers to talk with their instructor and classmates. I was a sounding board for their ideas and their confusions, whereupon I’d prompt them to read each other’s drafts, facilitate their feedback, encourage them to adhere to genre conventions, and help to interpret the rhetorical situation of their assignments. Such are some of the ways tutoring, as a form of assessment, influences the college writing experience at the group level.

One of the desired long-term outcomes of tutoring is for students to transfer that knowledge to new situations. For example, I saw some of my recurring students develop as writers during the process of multiple consultations. One of my students, in particular, (a multilingual writer) slowly began to appreciate how the nuances of grammar affect meaning when I pointed out patterns of verb tense errors as we read. She was eager to know how seemingly small differences in grammar can lead to significant changes in meaning. I suggested that, when drafting, she mark and attempt to resolve any problematic grammar she noticed before she came to the Writing Center. The purpose was not just so we could scan for correctness but also discuss how she addressed errors. With repetition, that practice became part of her revision process when she met with her dissertation advisor. This is one of the ways my tutoring practices influenced more than just the immediate consultation.

Assessment aside, another persistent concern of mine while I was tutoring had to do with language differences. The Writing Center practicum helped me to develop a keener understanding of language development when I worked with students of diverse ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds. I got to hear them speak, read their writing, and understand the different ways they use English. Also, by studying literacy and considering the circumstances that contribute to how we learn language, I recognized that tutoring others to learn English has implications extending beyond the Writing Center. For instance, it got me to question what tutoring does to and not just for a student. I recall one consultation in which I was tutoring an African-American student, where the goal of our consultation was to proofread. This student’s writing reflected the grammatical features of African-American Vernacular English. I pointed out some of the differences between AAVE and Standard American academic English, which she was all too happy to address, given that she too had a good idea of what college-level writing sounded like. But when I thought about what happened in that consultation, it was not just simple help with proofreading. I was uneasy evaluating this student’s writing, because the “errors” were distinctive features of her valued home dialect.

Cases like this gave me an angle from which to think about important threshold concepts in the capstone course. In Naming What We Know, Paul Kei Matsuda argues that writing involves the negotiation of language differences (Adler-Kassner and Wardle 68-70). This threshold concept recognizes the difference of features within and among languages as represented in writing. When we tutors assess student writing, we also assess language features in a way that upholds a conventional standard of English that is valued over other Englishes. Matsuda calls this a policy of “unidirectional English monolingualism” (637). Upon engaging this concept explicitly in the reading, I interpreted Matsuda’s position as call for compromise between writers, readers, and teachers: that translingual/multilingual writers will sometimes have to surrender some of their language features in certain situations and that teachers and readers must withdraw from treating Standard Academic English as an objective standard for writing. Had I not come to appreciate that the English language has inherent differences, I fear I would have tutored oblivious to how we embody our standards, inclined to see multilingual students and speakers of non-dominant English as needing to be “fixed.” And perhaps I did see them that way at the outset. However, I realized that sociolinguistic privilege is the act of judging how others communicate, imposing my English on any non-native speaker during tutoring. Thus I felt apprehensive at being an agent of the institution, one who metes and doles out the rules unto deficient writers. The issue of how exactly tutors can negotiate language differences between multilingual and writers of non-dominant English dialects is something I need to continue to explore so that I can perform my role in a socially responsible way.

Because of experiences like these, tutoring has made me think differently about people, not just about writing. By immersing myself in literacy and rhetorical studies, as well as writing center theory and practice, I began to understand how studying writing involves looking at where it’s situated and what it does, which can tell us things about people's assumptions, values, and motives.

The Role of Background, Writing Center, and Curriculum in Developing Understanding

In the preceding discussion, Mikael demonstrates concerns about language, identity, ideology, and gatekeeping with which established members of the field of Writing Studies also grapple. His narrative demonstrates that by that point in his education he had moved into a space where he saw connections between concepts and ideas that were previously unconnected in his mind (proofreading for standard English and the values of various dialects). Mikael now saw his own role differently than before (as a tutor he was no longer just another helpful set of eyes, but an “agent of the institution,” moving students toward a standard, white, middle-class, usage of English—a version of English he himself mastered long ago, as a young immigrant). The connections he makes allow him to ask new questions, in the language of the discipline—the kinds of questions that published scholars ask: what does tutoring do to students? Do tutors have the right to determine which version of English is most valuable? Mikael uses the discourse of the field in this reflection: he talks about “enacting standards,” “enabling or constraining language use,” “higher order aspects of writing,” and assessment as a “dialogic process.” He sounds like a (new) member of the field, and he is engaging difficult and largely unanswerable questions with which members of the field grapple. It seems to us that this is what it looks like for an undergraduate student to move to a “post-liminal space” around writing threshold concepts.

How did Mikael get to the place where he could think about, talk about, and embody difficult threshold concepts in this way? As we’ve talked and written together across many months, three contributory elements have risen to the surface: Mikael’s background and the dispositions they shaped; his experiences in a writing center that encouraged inquiry, dialogue, and reflective practice; and a curriculum that engaged students in research, theory, and practice across time. Next, we take up each of these in turn, first providing an overview and then turning to Mikael’s own description of the importance of each element. During this discussion, Mikael will also comment on areas where his learning was constrained or impeded.

Influence of Mikael’s Background

In terms of background, what’s risen to the surface for us are the experiences Mikael has had that seemed to instill certain learning dispositions that kept him open and available for learning across difficult spaces, and as someone who persists in the face of difficulty. Those include his experiences as an immigrant, a language learner, and an oldest child responsible for his own educational decisions. Below, in Mikael’s description of his background, we see illustrated many of the dispositions we described earlier: a generalized intellectual curiosity coupled with open-mindedness towards learning academic subjects, which were in turn supported by his sense of planning and ownership of his own education.

Mikael’s Story: Background

I’ve lived most of my life in Orlando, Florida. Though I was born in the U.S., I spent the first seven years of my life in Guayaquil, Ecuador before my family and I emigrated to the U.S. After moving, I became the eldest brother of two siblings in a family of five. My father has a high school education, while my mother attended some college, making me the first in my immediate family to earn a college degree. Wanting a better economic future than Ecuador could offer them, my parents brought us to the U.S. to begin new lives. Spanish was my first language (which we still speak at home), although I did learn some English during my early schooling; I speak and write now as a “native” English language learner.

I can’t recall how or when my learning habits developed, except to say that I have been inclined to abstract and to learn visually for as long as I can remember. I also liked to rely on both physical representations of the world, such as drawings or maps, as well as mental representations, to make sense of it. I did well throughout school, and my strongest subjects were reading, language arts, and history, though I struggled with mathematics. This is not to say that achieving good grades was easy, but I worked for them because my self-esteem was largely built on my own progress. School was what I was good at, and I needed to keep it that way.

After I became a full-time college student in the fall of 2012, I kept an open mind toward choosing a major while I worked on my Associate’s degree. I had no idea what I wanted to do for the rest of my life, but I knew I could narrow my college education down to what I was good at learning and/or what I enjoyed. In the fall of 2013, I transferred to the University of Central Florida, due to its proximity to home and the financial aid opportunities it provided. As with many college students, my motive for attending college was economic—to acquire skills that would make me employable. I valued majoring in something that balanced interesting subject matter with job preparation, but I was indecisive. For the next two years, I would end up switching from English, to psychology, and then to writing and rhetoric.

While majoring in psychology, I learned about the University Writing Center (UWC). The prospect of not only being employed but also being able to develop my own writing skills appealed to me. I enrolled in the required tutor-education course and tutored, initially, three hours a week. Among other things, the course (commonly called the “practicum”) activities helped illuminate my past writing experiences, and gave me a language with which to describe how learning takes place. That semester, I also familiarized myself with the writing and rhetoric course offerings, taking note of how courses like Professional Editing and Argumentative Writing seemed aligned with my idea of employment preparation.

The Writing Center and Mikael’s Experience In It

A number of features of the writing center experience contributed to Mikael’s ability to more deeply engage with threshold concepts of writing across time: community-based inquiry and discourse, continued re-exposure to difficult ideas and reflection on that experience, and learning-as-doing. As a peer tutor of writing, Mikael became involved in a variety of learning experiences in the Writing Center: the required tutor-education practicum; participation in a weekly ongoing tutor-education seminar after completing the introductory course, including student-led inquiry projects; reflective dialogue via an internal Writing Center weblog and break room conversations; and regular observations of tutoring and written reflections about them.

The Writing Center practicum introduced tutors from across the disciplines to research, theory, and practice of writing center work. Its goal was not only to enable novice peer tutors to work effectively in the Writing Center, but also to introduce them to writing center studies as a field of disciplinary knowledge-making. A guiding assumption of this course was that learning is doing, and so novices tutor three hours each week, from the second week of the course. This consistent practice in embodying/enacting ideas from the tutoring course seems promising if our goal is to help students learn threshold concepts—which require much more than knowing about. In addition to experiencing tutoring, central to tutor education was the opportunity to engage with the Writing Center as a site of research. One way that tutors try on this role is by carrying out a small-scale research study of their own, in which they record and transcribe a tutoring consultation, then analyze it, via discourse analysis. One purpose is to understand how patterns of talk shape the work of consulting. In addition to studying their own talk and tutoring practices, consultants frequently observe and analyze the tutoring practices of their peers. Periodic observation reports invite tutors to examine the routines they witness against the research-based practices they study in the course. Consultants also post reflections about their tutoring experiences on the Writing Center blog each week, then comment on the reflections of their peers. This dialogic writing, like the work of the entire course, is intended to prompt tutors to develop as reflective practitioners, wondering at every turn, not merely what to do during a challenging consultation, but why. This understanding of not only what but why seems central to a learner’s ability to grasp threshold concepts.

Mikael’ Story: Becoming a Tutor in the Writing Center

The initial Writing Center tutor-education course was challenging, not just because the content was difficult, but because it challenged students epistemically, which is to say that it pushed us to consider how we understand not only writing, but also learning. As for the tutoring itself, my technique was initially clumsy, and although I had a good grasp of grammar and language structure, this knowledge did not make me a confident tutor. Understandably, I was focused more on the procedural aspects of tutoring. Yet, procedural knowledge alone does not make an effective tutor.

I recall one consultation I described to Mark in his capacity as the UWC Director. I claimed that the student appeared to have learned something, and Mark asked, “How do you know?” At the heart of his philosophy of tutoring (and, therefore, the tutor-education course) was that “learning is doing.” Based on my experience, this means that learning to write well relies on practice, not lecture, so that students can evaluate the outcomes of their choices as writers. As I struggled to accept how learning works, I recall holding on to a “transference” model of learning early in the course, a model where the learner receives knowledge conferred by a higher authority. It is a conception that does not account for what learning actually looks like. I departed from this notion because the work that I did throughout the course and beyond taught me otherwise. I also believe that being disposed to think open-mindedly towards interpreting my own consultations, as well as willing to seek understanding through self-observation helped me to think generatively about tutoring and learning. Once I practiced, observed, and reflected on my work, I underwent a reconception about what counts as learning and knowledge-making in our discipline. Furthermore, sharing my experiences with my Writing Center peers via activities and reflective dialogue further reified how learning is provoked and mediated by the local social context. Activities—not lecture—drove most of the learning in this community of practice, which now brings me to what the assignments in the tutor-education course taught me.

Two of the course features that prompted me to rethink what learning looks like were observation reports, followed by the tutoring conversation analysis. I happened to enjoy exploratory and reflective writing and it was fortuitous that these assignments were exercises of focused, critical thought, the kind where I would need to unravel what happened and why by recognizing patterns of talk and behavior. For example, in the third observation report, I noticed the tutor’s move to make revision collaborative by relinquishing control of the physical draft while prompting the tutee to write notes on the margins. I then explained the implications of his tutoring choices. Such writing also required a degree of reflective abstraction, of speculating about alternative choices the tutor could have made, how the tutee might have responded, and what the possible outcomes might have been. The transcript analysis assignment prompted similar work, but instead of observing and speculating about the tutoring of my peers, I had to record, transcribe, and analyze one of my own sessions. This was investigative work, which stimulated me and made me want to probe deeper into the intricacies of conversation; by focusing on patterns of talk between myself and a tutee, I was able to gain insight as to what I could change in my own behavior to tutor more productively. These activities meshed well with the dispositions I brought because they relied on open-minded thinking that questions what is given and breaks it down, pursues rational, developed, well-supported answers, and encourages multiple interpretations.

The course was, for me, a place of intrinsic investment and personal development. It was an experience laced with intellectual, inquiry-driven activities, which gave me room to embody the thinking dispositions I brought with me to college. Now that I’ve become more familiar with threshold concepts, it seems evident to me that writing is an act of embodied cognition (Bazerman and Tinberg): the role of the tutor is to guide tutees to focus, structure, and express their thoughts. Also clear is how reflection is critical for writerly development because the observation reports and transcription analysis helped me to think about how and why we write the way we do. Kevin Roozen writes that our identities are in a state of flux, a construction of our lived experiences and future engagements, whereupon writing constructs identity via the embodiment of lexis, genres, values, and thought processes embedded in our communities (51). Through observing, reflecting, and writing in the interest of inquiry, we were practitioners, figuring out what kind of peer tutors we were or wanted to be.

By the time I started my second semester at the Writing Center, I was in a better position to recognize not only how assessing writing shapes context and instruction (Scott & Inoue) but also how writing involves a negotiation of language differences (Matsuda).

Mikael’s Experience in the Writing and Rhetoric Major

The curriculum of the Writing and Rhetoric major (of which the Writing Center practicum was a part) contributed to Mikael’s learning of threshold concepts in several additional ways: by exposing students to several threshold concepts; by providing students opportunities to encounter these repeatedly across time; and by engaging students not only in the practices of composing but also in theoretical consideration of how writing works and is enacted.

The major that Mikael enrolled in was quite new and untested at the time, enrolling its first cohort of students in Summer 2014. The major had been designed by the faculty from the ground up beginning in 2010. Although initial planning of that major did not entail discussion of threshold concepts (with which the faculty at that time were not familiar), later analysis and reflection illustrated the ways that threshold concepts were threaded throughout the courses that made up the program of study, and they were emphasized and reflected on in the senior capstone course in which Mikael enrolled.

The curriculum hinged on the threshold concept that Adler-Kassner and Wardle describe as “writing is [both] an activity and a subject of study” (15). Three required core courses were Rhetoric and Civic Engagement, Researching Writing and Literacy, and Professional Lives and Literacy Practices, and Mikael completed them all (albeit out of sequence). These were intended to acquaint students with three overarching threshold concepts:

-

Writing and rhetoric is a discipline with unique and useful knowledge;

-

Writing is a rhetorical activity that speaks to specific contexts through recognizable conventions;

-

Writing and rhetoric enact identities and value systems (Scott and Wardle 129).

This third threshold concept (and variations of it) proved particularly important in Mikael’s experiences, as we saw in his earlier description of threshold concepts he had worked through.

The curriculum enacted the belief that rhetorical dexterity is “gained through study, practice, and performance across time.” Thus, it entailed:

-

additional electives in a category described as “Extending Theories and Histories of Writing, Rhetoric, and Literacy,”

-

additional courses emphasizing application of writing principles in varied contexts,

-

a required internship or practicum, and

-

a culminating e-portfolio and capstone course, where “[students] integrate the threshold concepts and other disciplinary knowledge they have developed and enacted, examining how they have learned to transfer writing competencies and strategies across different contexts” (Scott and Wardle 131).

The goal of the curriculum, then, is to enroll students in core courses that expose (and re-expose) them to select threshold concepts; then in courses that extend, recognize, and enact threshold concepts and competencies; then in a practicum experience that further enacts and reflects on those threshold concepts; and finally in the capstone and in designing an e-portfolio that interprets and integrates “enactment of” threshold concepts and helps students to build a “theory of transfer” (Scott and Wardle 133). This element of “exposure” and “re-exposure” was key to Mikael’s ability to learn difficult threshold concepts—although it didn’t always work as planned.

The faculty recognized, of course, that “it is impossible to predict when and how students will ‘cross’ the threshold toward which the major directs them,” and that they are likely to do this in different ways, at different times, as a result of their own experiences, dispositions, and histories (Scott and Wardle 132).

Faculty attempted to structure the major in a way that would help students encounter (and re-encounter) key ideas and concepts across time, in coursework, practical application, and reflection. Of course, in reality, the major did not work as neatly as hoped. Students took courses out of order, took many more at one time than was desirable, took the capstone before their senior year, engaged in practicum experiences that were variously meaningful, and found the portfolio more or less useful. Here, we pause to let Mikael discuss his progress in the major and the significance of his particular path.

Mikael’s Story: Traversing the Major

What did I do in the major that helped me to learn threshold concepts, and how did the major afford and constrain this process? The major was composed of core courses, advanced courses, and electives; however, like many students, I did not take the core courses in the prescribed sequence. I have revisited syllabi, readings, assignment instructions, and draft work in order to trace my thought processes and identify experiences conducive to learning two threshold concepts: how assessing writing shapes contexts and instruction and writing involves the negotiation of language differences.

In the courses I took, instructors seldom, if ever, made explicit connections to what other instructors taught; this meant that knowledge gained in one course did not immediately or easily connect with knowledge in another. Not only were the courses each distinct in both style of instruction and content, none besides Theory & Practice of Tutoring Writing and the capstone mentioned threshold concepts explicitly. Despite the fact that the curriculum was supposed to be coherent and connected, as a student, I had to do most of the work of making those connections. Perhaps I would not know what I know now if I had not worked independently to make deliberate connections across courses and concepts. However, making connections on my own was challenging. In this way, the curriculum did not work as the designers planned.

In order to learn how assessing writing shapes contexts and instruction, I had to become meta-aware of the communities of practice I was part of. Literacy and Technology was first to help me in this regard. The instructor based the course around New Literacy Studies and the core concepts of literacy as “ecology” as well as “practices, events, values and awareness.” While taking the course, I completed a case study research assignment in which my classmates and I all submitted three personal anecdotes about the technological literacies we’ve acquired. We then compiled the anecdotes into a corpus, processed the corpus through a word-sifting software, recognized patterns of terms and phrases used, and drew conclusions about our perceptions of how literacy functions in our lives—all to write the case study. Because of the data from the anecdotes as well as the pattern of words from the corpus, it seemed as though the multi-literacies the class embodied (such as programming languages or digital art tools) were all shaped by the context of education. Despite their diverse histories and educations, many of my classmates referenced schooling as a place where they had to acquire literacies beyond reading and writing so as to engage in the practices of their specific programs and courses. This assignment taught me that literacy is too diverse to reduce it to mere inscriptive, mono-modal practices. Furthermore, since I saw that the context of education required that students adapt to its methods of learning, the values and assumptions attached to those methods must also be shaping how students learn (or so I was able to intuit). I got an A on the assignment; but more rewarding than the grade was when the instructor acknowledged the insights I gained and talked with me further about literacy, probing the implications of what I had learned. The insights gained throughout the course became useful when I applied them towards my role as a tutor in the writing center.

Another course that opened my eyes to how assessment shapes contexts and instruction was Researching Writing and Literacy, which I took during my second semester in the major. This course did not build on the topics and theories covered in the previous semester. Instead, the instructor focused on knowledge paradigms, bodies of scholarship, as well as methods of inquiry utilized by the field of Writing Studies. In addition to oral and written discussions, I completed a research proposal where I selected a topic related to communication, narrowed down on the study of Reddit users and their literacy practices, constructed a theoretical framework to apply, and chose methodologies pertinent to what I wanted to learn. The object of the research was to learn about how posting and commenting behavior was shaped by the rules embedded in the subreddits. Although I didn’t carry out the actual research, I had to draw on scholarship about literacy, justify my methods, and finally organize it all to render my proposal readable for a member of the field because, ultimately, the goal of the research was to contribute to ongoing scholarly conversations. In completing the course, I learned to more deeply appreciate “academic genres” and why college papers are expected to be structured and formatted the way they are. Clearer than ever, I recognized that there was no such thing as “general writing” because good writing depends on the very contexts that call it into being. This is how I could attain a kind of visceral awareness that to assess writing as a tutor is to invoke the values of the institutions around us. Only in capstone was I prompted to articulate this awareness, however, because that was the only site other than the UWC practicum where threshold concepts were made explicit.

As for how I learned that writing involves the negotiation of language differences, perhaps I found that I knew this only when confronted with apprehension at attempting to “fix” a student’s dialect—or perhaps when the capstone course prompted me to think about what I knew about language differences. Whatever the case, it was not the subject of any one course, nor did any course address this issue at length. Rather, I suspect the curriculum addressed the threshold concept indirectly. To illustrate: in Rhetoric and Civic Engagement, I interrogated the meaning(s) of rhetorical citizenship through expository/reflective essays as well as comparative analyses of civic engagement methods utilized by human rights groups present in Central Florida. Indirectly, I was also invited to reflect on the interdependent hierarchies of class, ideology, and language—which give rise to power dynamics, or more immediately apparent, the dynamic of Standard English/native speakers and “others.” Following that, Literacy and Technology and the writing of David Barton gave me the opportunity to compare the “autonomous model,” which holds literacy as something neutral and transferable, to that of the “ideological model” which acknowledges the socio-cultural embeddedness of literacy. This knowledge, along with the case study insights and my growing awareness of how language standards constrain some users while enabling others, compelled me to critically reconsider my position as a writing tutor in relation to the context around me, and, as a result, I began to feel a gradual, unpleasant self-awareness.

Though some student writers approach tutors as peers to collaborate with, others approach us with “fix,” “change,” and “teach” in mind. To these students, I was part of the “in-group.” I had the advantage of being a user of Standard Academic English who could look at a student’s draft and validate it. After my coursework and reflections, it felt as though none of what I was doing at the Writing Center was neutral; halfway into my major, I was being thrust out of my own ethnocentrism and made to acknowledge the implications of not just imposing our literacies on other people but also of failing to acknowledge and value literacies unlike our own.

When I started the major, I had enough cultural maturity to detect some of the more overt inequalities affecting people, but perhaps courses like Rhetoric and Civic Engagement laid the groundwork for me to truly locate myself at least within the framework of sociolinguistic advantage (a middle-class citizen who worked hard to speak and write like a native speaker, even though I am not one) and then relate myself to others in ways beyond just race, education, and income. Then, the curriculum extended this ongoing metacognitive awareness while tutoring provided experience I could draw from to contextualize this troublesome knowledge. This new awareness—though not total or sudden—prompted me to resist the mindset I had at the time, with irreversible implications for my identity.

To evoke Roozen’s thoughts once more: if writing can be an expression of identity within a given situation or community, how could writing assessment be anything but another expression of identity, especially an ideological one? He writes, “we become more comfortable making the rhetorical and generic moves [of our] communities” as our identities “align with its interests and values” (51); this suggests caution in becoming too comfortable. If writing assessment at the college level evokes cultural values, both overt and subtle, then tutoring likewise is never a neutral act, which disperses the illusion that I can fairly negotiate language differences, given who I am.

These experiences have shown me that threshold concepts aren’t something you know as much as something you embody through what you do. Part of the reason I think I have come to engage and integrate threshold concepts was because I was motivated to change and grow as a tutor: although my education had proven to be intellectually rewarding, it was now proving to be valuable to my job at the University Writing Center, and therefore, to my own sense of self-competence. Some courses helped me understand threshold concepts more than others. Those that helped not only encouraged the drafting, feedback, and revision process, but also afforded opportunities to do exploratory thinking to draw my own conclusions. Learning in the major was never about having flawless ideas or writing a good paper, but it also wasn’t until I applied these ideas towards my experiences and observations at the writing center that they became useful by informing/challenging the values and assumptions of my tutoring. Through this process, I was reconceptualizing myself as a student, as a writer, and as a tutor in light of troublesome new knowledge about how we use language.

Conclusion

In this article, we set out to examine what deep learning of writing-related threshold concepts looks like and what the constraints and affordances were for one student in that learning process. Deep learning is described by Tagg as focusing on making meaning, actively constructing knowledge, relating new knowledge to prior knowledge, integrating knowledge into “semantic memory,” relating new knowledge to broader theoretical ideas, being mindful, and making learning enjoyable (81). It seems clear that Mikael was motivated to engage in this kind of learning due to his own life experiences and dispositions, and that many (but not all) of his experiences in the major—but particularly in the University Writing Center—provided space where he could do this to engage writing-related threshold concepts. Even in courses that weren’t making connections to other courses or explicitly to threshold concepts, he was engaging in activity, project-based learning that helped broaden his ideas about literacy and writing and kept him interested in the substance of the courses and the major. Throughout his coursework, he regularly engaged in some of the AAC&U “high impact” practices, including collaborative learning and research.

His ability to engage with threshold concepts about writing in deep ways was certainly a long-term process. His experiences indicate that repetition, application, reflection, connections across time, and dialogue with both peers and faculty were integral to his ability to engage in deep learning. It seemed centrally important for him to connect theory to practice and to connect experiences and ideas from one context to other contexts (he notes, for example, that “it wasn’t until I connected these ideas to observations and experiences in other contexts that they became useful”). The Writing Center experience as a whole required constant reflection and connection-making, as did the capstone course; the difference was that the Writing Center could enable this work across several semesters in a way that one course could not. Since Mikael’s time in the tutor education class, Mark has worked to even more explicitly framed tutor education around threshold concepts. Given that many students, like Mikael, work as peer tutors for multiple semesters, the Writing Center is a site where threshold concepts can be connected with theories in coursework across time—even if (perhaps especially if) those threshold concepts are not explicitly named and connected in those other courses.

In fact, reflection and explicit connection-making across courses and ideas appeared absent in many classes, as Mikael has described them above. In retrospect, he notes that he often had to work on his own to make connections between disparate classes and instructors, and his own motivation—as well as dispositions for engaging, reflecting, asking questions, and making connections—kicked in to help him succeed at deep learning of threshold concepts when curricular design did not. For reasons beyond our ability to pinpoint here, Mikael came to the Writing and Rhetoric major with many of the thinking dispositions identified by Perkins, Jay and Tishman: he demonstrated sustained intellectual curiosity, he constantly sought to clarify and understand, he was intellectually careful, looked for and evaluated reasons, and was reflective. These dispositions preceded his work in the major, and our work as faculty can’t be given credit for them. The specific activities of the Writing Center and capstone—infused with active learning, dialogue, and reflection—may have helped refine and extend these dispositions, and certainly affirmed them—but they did not create them. Many other students in those two learning contexts struggled with the very activities that Mikael identified as central to his ability to cross from a liminal to a post-liminal space.

This disparity between Mikael’s experiences and those of some of his classmates brings us to the most difficult questions: How we can extrapolate from his experiences as we work to help other students engage in the same kind of deep learning? How can programs effectively reach students who do not initially seem to be working with the same learning dispositions? Our discussions with Mikael during the past year and a half have illustrated that he often engaged in deep learning across contexts in spite of what happened in the curriculum; thus, when he encountered invitations to make connections and engage in deep reflection in the Writing Center and capstone, he was enthusiastic about doing so. However, other students were not as able to make connections across courses and contexts on their own without scaffolding and cueing. Thus, in the capstone course, for example, while Mikael was continually relating named threshold concepts back to experiences in previous classes where the concepts had only been implied, other students were frustrated and angry. They wondered why they were only now learning new names and ideas in the final course. They were confused about the lack of named concepts in previous courses. They had trouble recognizing that ideas they were now discussing explicitly were implicitly present in nearly all their other coursework. As faculty members involved in the creation of the major (and, for Elizabeth, in the creation of the department), this lack of connection is disappointing. But it should not be surprising. It seems to be the nature of faculty members and courses to become their own islands; even curricula of a new major designed to be integrated can quickly become a collection of isolated courses taught by isolated and idiosyncratic faculty members. After all, faculty are busy and overworked, and there are few structured opportunities for faculty to learn what others are doing in their classrooms; thus it can be difficult to connect to them. Faculty members even in a Writing and Rhetoric department come from different intellectual backgrounds and thus value and name concepts differently. To a certain degree, this is a healthy and productive result of intellectual diversity and freedom. However, to the extent that it impedes student learning, it is a constraint. To provide the connection and cohesion that students need while also maintaining the freedom that faculty value would require a change in the way departments generally do their work.

While capstone courses are named as a central AAC&U “high impact” practice, Mikael’s experience makes clear that if we want students who vary in abilities, backgrounds, identities, and dispositions to make meaningful connections between ideas in the major, the opportunity for that connection-making can’t be delayed until the capstone course. Additionally, while the Writing Center is where Mikael made the most strides in his integration of knowledge, not all students can work in the Writing Center to fulfill the practicum requirement for the major. Most students, in fact, complete it through internships in organizations outside the university. These are generally not designed with the kind of reflective support for engaged learning that is evident in the Writing Center curriculum (see Dias et al). While internships are important high impact practices, they can clearly have more impact if they include ongoing connection to and opportunities for reflection on how the practices in that space relate to concepts from coursework. For Mikael, the opportunities for extended reflection and for enacting ideas in practice across time that were provided in the Writing Center were perhaps the most important catalyst for deep learning of threshold concepts. How are other students to make such connections if they do not have this guided experience, and if the courses they take feel disconnected to them—and if they don’t have opportunities for embodied learning or enacting disciplinary knowledge?

One way for instructors to become aware of dispositions and backgrounds that are affecting students’ abilities to make connections might be to intentionally cue students to connect new and difficult concepts and material to their own previous experiences and to aid them in reflecting on connections or impediments as they take up the concepts. For example, in a previous study written with a student, Wardle and Nicolette Mercer Clement note that Nicolette’s struggles with material in an Honors Seminar might have been mitigated had she first been asked to reflect on how the course readings intersected with her personal experiences. Because the course material implicitly critiqued and conflicted with her own culture and family background and values, she found herself in a double bind when asked to write drawing on the theorists being studied. One way to help students learn to reflect on conflicts like these and integrated difficult and disparate ideas might be to

assign some low-stakes assignments asking students to consider how the ideas in the course readings relate to their own previous experiences, values, and knowledge. What is their relationship to and experience with [the ideas of the course] for example? How do the ideas in the readings correspond to or conflict with the ideas students bring with them? Students might be invited to actively explain the relationship of what they are learning to what they already know and believe. Such reflective, low-stakes assignments...may assist students in understanding why the assignments are difficult and assist teachers in knowing why some students might be struggling. (176-7)

Our view is that design and implementation of curricula would need to be different if the goal was to see students engage in deep learning of threshold concepts across time, and for students to be supported across multiple courses and contexts as they take the necessary time to successfully move through liminality. Faculty would need to consider as a group what the learning end goals are, what threshold concepts should be reaffirmed across time and courses, what language they are all using to discuss these concepts, and how to learn enough about what other faculty are doing to help students meaningfully reflect on connections across courses. This is a tall order.

Further Questions & Implications

The problems and challenges we’ve outlined above and the suggested need for more integrated courses and faculty lead to a number of questions that we can only pose here and hope others in the field will take up.

First, while writing majors around the country have identified learning outcomes for courses and programs, what would it look like to also identify threshold concepts that might be threaded throughout the major? (Heidi Estrem takes up the important distinction between outcomes and threshold concepts in Threshold Concepts and Student Learning Outcomes). And what would be the threshold concepts of writing that we hope students learn? These wouldn’t need to be the same across institutions, of course, but within departments, might these be identified and agreed upon by faculty from disparate intellectual backgrounds? Not as the only things that students should learn, but as the baseline concepts that all students should learn. When and how do students encounter them? What sorts of teaching practices and programmatic designs enable students to work through troublesome knowledge? What would conversations to identify these concepts look like? Elizabeth has given a number of workshops for departments in other disciplines asking them to do this very thing. The results have been engaging and collegial. Writing and Rhetoric faculty could usefully engage in the same experiences, as long as the conversations happen at the local level.

Once those threshold concepts for the major are identified, how do faculty create curricular pieces that are explicitly connected—how do they name these connections for themselves and help students see those connections? How can connections be maintained across time, when daily business and routines take over?

How do faculty design curricula that leave space for the disorientation of the liminal space—but provide structure and scaffolding to help students make progress through that space? How do we handle the deep discomforts of liminality in our own classrooms? In the capstone course described here, for example, the disorientation and “breakdowns” (as the students put it) experienced by many of the students were emotionally and intellectually difficult to support. Students cried frequently, and more than once an entire class period was devoted to exploring the feelings students had upon realizing the impact that certain threshold concepts had on their own sense of self (for example, one student was deeply distressed by the threshold concept “writing is not natural,” because her identity from a young age was as a “natural writer”). It would have been very easy simply to discard the difficult analysis and reflection and assign easier tasks. As a less experienced teacher, this is likely what Elizabeth would have done, given concerns about student evaluations and the lack of confidence that new teachers can have. However, because she was an experienced teacher and a full professor (and the department chair), she had the affordances to push through the liminal discomfort without fear of negative consequences from course evaluations or student complaints; she had both experience and job security (although the daily affective challenges of the class were still demanding). Her situation is not the norm, however. How can we empower less experienced teachers, and teachers with less job security, as they work to support students who are working through disorienting liminal spaces? If we are going to make connections with students in the most difficult of places and account for the dispositions, identity, and sense of self that all seem to shape engagement with threshold concepts, we have to train and support faculty at all levels across the curriculum to do this work, and design curricula that reaffirm challenging ideas across time. (As is the case so often in our field, labor issues here are a serious concern and impediment to fully realizing our goals).

Overall, Mikael’s reflections for this article, and Elizabeth and Mark’s experiences teaching the capstone course, training tutors, and designing curricula for writing majors have led us to recognize that when successful and deep learning of writing-related threshold concepts happens, there are many reasons for it: a confluence of activities, dispositions, backgrounds, experience—and time, both kairos and chronos. As faculty, there are many things that are beyond our control and for which we cannot take credit—sometimes students come to our courses with successful and dogged learning dispositions, habits, and practices honed by life experiences such as Mikael’s, and sometimes they are less well-prepared by previous experiences. But there are many things for which we are responsible, and can actively take responsibility: working to name threshold concepts about writing early and often across the major, helping students learn how to integrate and make connections across seemingly disparate contexts, helping students learn by doing, and aiding students in using theory to understand practice and vice versa. Even students like Mikael who come with dispositions for thinking and learning that enable them to succeed regardless of curricular failings still have more to learn, and we can afford or constrain that learning, depending on our willingness and ability to step outside of our silos and work to make explicit connections across our courses.

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda, et al. The Value of Troublesome Knowledge: Transfer and Threshold Concepts in Writing and History. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012. www.compositionforum.com/issue/26/troublesome-knowledge-threshold.php.

Adler-Kassner, Linda and Elizabeth Wardle. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State UP, 2015.

Ambrose, Susan A., et al. How Learning Works: Seven Research Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Jossey-Bass, 2010.

Barton, David. Literacy: An Introduction to the Ecology of Written Language. 2nd ed., Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Bazerman, Charles and Howard Tinberg. Writing is an Expression of Embodied Cognition. Edited by Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 75-5.

Biggs, John and Catherine Tang. Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 4th edition. McGraw Hill, 2011.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Harvard UP, 1993.

Burkhardt, Joanna. Teaching Information Literacy Reframed: 50+ Framework-Based Exercises for Creating Information-Literate Learners. Neal-Schuman, 2016.

Clark, Timothy. Ecocriticism on the Edge: The Anthropocene as a Threshold Concept. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015.

Cousin, Glynis. An Introduction to Threshold Concepts. Planet, vol. 17, 2006. www.ee.ucl.ac.uk/~mflanaga/Cousin%20Planet%2017.pdf.

---. Threshold Concepts: Old Wine in New Bottles or a New Form of Transactional Curriculum Inquiry? In Ray Land, Jan H.F. Meyer, and Jan Smith, eds. Threshold Concepts Within the Disciplines. Boston: Sense Publishers, 2008. 261-272.

Dias, Patrick, et al. Worlds Apart: Acting and Writing in Academic and Workplace Contexts. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1999.

Downs, Doug and Liane Robertson. Threshold Concepts in First-Year Composition. Edited by Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 105-121.

Driscoll, Dana and Jennifer Wells. Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, www.compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php.

Estrem, Heidi. Threshold Concepts and Student Learning Outcomes. Edited by Adler-Kassner and Wardle, pp. 89-104.

Giancarlo, Carol A. and Peter A. Facione. A Look Across Four Years at the Disposition Toward Critical Thinking Among Undergraduate Students. The Journal of General Education, vol. 50, no. 1, 2001, pp. 29-55.

Hamilton, Carole. Critical Thinking for Better Learning: New Insights from Cognitive Science. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.