Composition Forum 31, Spring 2015

http://compositionforum.com/issue/31/

Metagenre on the WPA-L: Transitional Threads as Nexus for Micro/Macro-level Discourse on the Dissertation

Abstract: In Carolyn Miller’s Rhetorical Community: The Cultural Basis of Genre, she revisits her assertion that genres are cultural artifacts and questions the nature of the relationship between micro-level, individual speech acts, and macro-level genres and systems. To demonstrate this relationship, I analyze meta-genre accounts of the dissertation posted on the Writing Program Administrator (WPA) listserv, a forum for Computer Mediated Communication (CMC). Within this discourse, I identify transitional threads—moments when the discussion shifts, which show the relationship between micro- and macro-level interaction on the listserv as well as constructions of the dissertation within Writing Studies. CMC highlights how micro-level speech acts aggregate and are impacted by macro-level culture, and it showcases the heterogeneity inherent in the rhetorical community of the listserv.

“[How do we…] understand the relationship between, on the one hand, the observable particular (and peculiar) actions of individual agents and, on the other, the abstract yet distinctive influence of a culture, a society, or an institution. Do speech acts, moves, episodic encounters - the micro-discursive levels - somehow cumulate, as I implied, and ‘add up to’ culture, to the Athenian polis, the scientific community, the Renaissance court? And if so, how? And exactly how do the macro-levels (genre, form of life, culture, etc.) contextualize the micro-levels? To put the matter most broadly, what is the relationship between the micro-levels and the macro-levels?” (Miller, Rhetorical 70)

In her 1984 article, Genre As Social Action, Carolyn Miller provides the rhetorical framework for analyzing genre that subsequently informs Rhetorical Genre Studies (RGS). She claims genre not just as a legitimate site for rhetorical work, carving out requisite territory for RGS and inviting further research, but, importantly, as a necessary space to understand social interactions. In fact, most scholarship in RGS{1} orients around the ideas put forth in this article, in particular, that genres develop out of “typified rhetorical actions based in recurrent situations” (Miller, Genre 159) and function as cultural artifacts. Thus, Miller’s article responds to contemporary scholarship of the time that categorized genre primarily by form or substance. Such readings of genre created closed systems of classification and discursive possibilities. Instead, Miller shifts our attention to what a genre accomplishes, what it does in interaction. She claims as important sites of study for RGS the “homely discourse” (163) we read and compose in our daily lives: scientific articles (Bazerman), graduate student writing (Berkenkotter), tax accounting discourse (Devitt), and management discourse (Orlikowski and Yates). Miller’s project was to develop a “stable classifying concept” of genre that was also “rhetorically sound” (151) in order to open up theoretical and pedagogical possibilities for understanding genre.

However, in her 1994 article, Rhetorical Community: The Cultural Basis of Genre, a powerful addendum to the 1984 manuscript, Miller reflects on the intervening decade, tracing the implications and resulting ambiguities of approaching genres as cultural artifacts. Miller was troubled by her metaphor, humbly citing in her introduction to the 1994 article, “At the time I didn’t think very carefully about what I meant by ‘cultural artefact’” (Miller 67). By invoking this metaphor, she tapped into a larger, interdisciplinary community interested in the relationships between micro- and macro-level interaction (for example, see Knorr-Cetina and Cicourel). Thus, she spends time in this follow-up examining what comes of her earlier contention, especially the resulting tension between micro-level, individual actions, and macro-level, collective action. Tying individual instances of genre to a rhetorical community poses a problem: by suggesting socio-rhetorical implications of genre at a collective level, there is a danger of losing a focus on individuals, of putting too much stock in representation, of attributing power to systems as opposed to discourse in social interaction.

On the 30th anniversary of Genre As Social Action, I heed the implications of examining genres as cultural artifacts and explore the question, “what is the relationship between the micro-levels and the macro-levels” in the realm of Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC)? Do individual accounts “add up to” cultural artifacts? Do they add up to culture? To approach these questions and associated tensions, I examine meta-genre (Giltrow, Meta-genre) accounts of the dissertation—those that define the genre and are posted on the Writing Program Administrator (WPA) listserv, a forum for Computer Mediated Communication (CMC). These meta-genre accounts constitute the most responsive discussion on the WPA listserv in January 2012, the intensity of which signals confusion over the contradictory “social action” the dissertation genre is meant to accomplish. More explicitly, my analysis focuses on transitional threads within this conversation—posts that successfully bring about a shift in discourse about the dissertation, which are successfully taken up by the rhetorical community of the listserv.

Transitional threads respond to situational kairos by confronting a rupture of the “communal decorum” (Miller, Rhetorical 74). Practically, transitional posts are ones that retitle an existing thread, highlighting a turn in the discussion. Such transitional posts typically revise the title of the email itself, often following the title form, “New Title X, (was Old Title Y),” and resulting responsiveness on the listserv develops into a transitional thread. Motives for retitling a thread are complex, but they serve to regulate and “police” (Johnson-Eilola and Selber 270) listserv discourse and demonstrate convention and propriety on the listserv. Transitional threads provide evidence of new ideas taking root on the listserv, reorganizing the macro-level structure. Most importantly, such threads serve as intersections between micro- and macro-level interaction, functioning as individual speech acts “distinctly influenced” (Miller, Rhetorical 70) by macro-level culture. Though they are individually authored, transitional threads are “an interactional accomplishment” (Gruber 30), representative of the listserv community functioning together.

Analyzing CMC in the context of this particular listserv discussion highlights the relationship between micro-level and macro-level interaction in two different realms: 1) discourse on the listserv alternates between micro- and macro-level discussion of the dissertation; and 2) each listserv post represents micro-level interaction on the listserv, and the accumulated threads, macro-level cultural artifacts. As such, transitional threads act “as the operational site of joint, reproducible social action, the nexus between private and public, singular and recurrent, micro and macro” (Miller, Rhetorical 74). By using CMC to examine the linkages between micro- and macro-level interaction within this rhetorical community through a focus on transitional threads, we can trace the slow accumulation of speech acts as they organize into threads, into meta-genre, into rhetorical community. Here, micro-level posts do add up to macro-level culture. Further, macro-level convention “contextualizes” (Miller, Rhetorical 70) what is valued on the micro-level, and the listserv’s self-regulation and subsequent use of transitional threads preserves these community conventions. The discursive record created by CMC maintains the heterogeneity of individual posts that, though never erased in genre, is certainly not highlighted in discussions of genre convention. Instead, analysis of CMC counteracts the normalizing tendency of genre, demonstrating the periodically fraught, tense relationship within the interactions that constitute macro-level culture.

Operationalizing Meta-genre in CMC

Meta-genre is a particular kind of “talk about genres” (Giltrow, Meta-genre 187). It is the talk that surrounds and outlines generic convention, a kind of “[atmosphere] of wording and activities” (Giltrow, Meta-genre 195). Such discussion is a rich site of information about a genre’s history, its constructed nature, the values of the community in which a genre develops, and the “shifting social dynamics of writing” (Starke-Meyerring et al. A-15). For instance, Doreen Starke-Meyerring et al. recently examined university web-materials about the dissertation and found, counterproductively, that these meta-genre accounts constitute the genre as a product, rather than a process. Meta-genre accounts, such as those examined by Starke-Meyerring et al., often take the form of how-to instructions or guidebooks, although instances of meta-genre are frequently found in less conspicuous spaces.

The listserv, for example, offers numerous meta-generic posts not specifically meant to instruct, though they effectively define convention and feature boundary work around genres in an organic setting. How-to lessons and conventions are derived from listserv posts. WPA-listserv instances of meta-genre discourse are particularly instructive since they represent talk that is naturally occurring and not primarily intended to teach genre. In fact, Susan Herring suggests that CMC is especially prone to meta-linguistic discussion since “CMC persists as text on a screen and is subject to conscious reflection in ways that spoken language is not” (Interactional n.pg.). Thus, meta-genre accounts help elicit the tacit expectations of genre that might not emerge when individuals are formally asked to “teach” genre; as Giltrow notes, “[t]acitness explains discrepancies between what language-users do and what they say about what they do” (Giltrow, “Legends” n.pg.). Further, CMC usefully troubles what we know about genre, offering new insight into the long-standing questions of how genre is constituted and dispersed. As Miller recommends, it allows us to look past the “commonsense” (Paré, Starke-Meyerring, and McAlpine, “Dissertation” 187) nature of genre to its constructed nature.

Examining CMC meta-genre accounts allows us to simultaneously squint at genre, looking carefully and closely at individual accounts, and step back to examine how discourse functions in its wholeness, on a macro-level. We see both the contentious, heterogeneous nature of individual speech acts, and how they ultimately aggregate in certain constructs, like dissertation conventions. By operationalizing the term meta-genre for analysis and using CMC to trace connections between micro- and macro-level interaction, we can analyze a community’s stance toward and understanding of genre and its implicit conventions.

Dissertation as Genre

In Genre as Social Action, Carolyn Miller argues that “the absence of a normative whole at [the level of genre] poses problems of certain kinds. It means that the interpreter must have a strong understanding of forms at both higher and lower levels, in order to bridge the gap at the level of genre” (Genre 165). The dissertation as it is constructed in Writing Studies suffers from this “absence” that Miller describes, as well as the resulting problems. The implications for this lack of genre recognition are serious: for doctoral students, there is a less than 50 % completion rate, increasingly meager job prospects, and significant debt (Golde and Dore; Council of Graduate Schools). Further, faculty and academia at large are in an uproar over the perceived “dissertation crisis” (Berman, n. pg.); this is demonstrated by the fervent interest in the discussion about the dissertation on the WPA listserv that constitutes my dataset. For some on the listserv, the dissertation is a “bogus requirement arising from some ancient ideas about what it means to belong to the club,” which calls for “writing that goes beyond a sophisticated form of academic hazing.” However, others posit that requisite “[negotiations] with my mentors and teachers […] taught me an awful lot about how to be a professional,” and “[t]he dissertation provides a springboard for publication and other scholarly activities” (excerpts from the WPA listserv discourse that constitutes my dataset). Such disparate meta-generic accounts of the dissertation largely support Anthony Paré, Doreen Starke-Meyerring and Lynn McAlpine’s reading of the dissertation as multi-genre because it must accomplish myriad social actions (“Dissertation”).

In other venues I have also attended to the complex network of sub-genres that constitute the dissertation, arguing that they comprise a genre ecology (Pantelides). But for the purposes of this study, I will focus on how listserv posts orient to a notion of “the dissertation” and on how the meta-genre accounts on the listserv construct the dissertation as a genre in crisis, in need of genre change. Though arguably not its intent, the primary function of the selected listserv discourse is to confront the rupture of dissertation convention at the level of genre and as it exists in Writing Studies.

Methods of Analysis

I use Discourse Analysis{2} of meta-genre accounts of the dissertation posted on the WPA listerv to examine how the dissertation is constructed in accessible, public written discourse. Discourse analysis is a “largely inductive process in which the initial search for what might be interesting should normally precede quantification, coding, or the adoption of some appropriate theoretical model” (Swales 95). This descriptive approach to discourse attempts to glean meaning from talk and text as opposed to bringing meaning to talk and text with prescribed categories or theories; such analysis “seeks to explicate the knowledge that practice creates” (Miller, Genre 155). Further, I include most posts in full (and provide significant excerpts from others) within the text to provide a sufficient context for analysis. Although the WPA listserv archives are publicly available, I follow the lead of other CMC researchers (Herring, “Ethical”) and refer to each post’s author by a pseudonym since the authors are not the subject of my inquiry.

The WPA Listerv as Macro-level Rhetorical Community

Although at its inception many hoped that CMC might be a more perfect discursive space, one less implicated by the bias inherent in face-to-face interaction, subsequent research has demonstrated the power dynamics at work in CMC of all kinds (for an example of power relationships in listserv discourse, in particular, see Matsuda). However, asynchronous CMC does introduce fairly dramatic differences in discourse from speech and written narrative. In particular, CMC is characterized by a “lack of simultaneous feedback”—meaning that one might post a comment and never receive a response, or might only receive a response days later—and “disrupted turn adjacency”—meaning that the discussion usually does not follow expected turn-taking natural in speech (Linguistic Herring).

The case of listserv discussion is further unique within asynchronous CMC. Although blogs as genre have been considered extensively (for example, see Miller and Shepard Questions; Miller and Shepard Blogging; Herring et al.; Grafton; Maurer), and listserv posts share much in common with blog posts, there are important differences. The audience for the WPA listserv is, like blogs, self-selecting, but listserv posts are delivered through email, and, though a public archive exists, the resulting conversation is somewhat more ephemeral than that which appears on a blog because of a difference in structure. As David Elias and Deborah Brown note in their work on listserv discourse, “[Email] allows, though it does not require, editing and proofreading as well as reflection by the writer. Yet it has an element of spontaneity and personal exchange, like the telephone, in its timeliness.“ The purpose of a blog is to permanently archive posts to create an accessible space for users to return to existing conversations. Further, blogs often have comment forums that extend a post’s life, but unlike response emails, which have a certain independence, comments are generally attached to an initial blog post and become part of its discursive record. This structure privileges author(s) of blogs, rather than readers/commenters.

An archive is an inherent part of the structure of a blog. When a reader accesses a new blog post, there are archived posts visible for the reader to engage with, through reading or commenting. On the other hand, readers experience listserv posts as emails, generally a one-day read in the inbox. Emails may be read, deleted, or perhaps saved for a later date, but in this way they are less permanent than a blog post, and the “permanent” archive of conversations is housed in a wholly different site, in itself not structured for easy scanning and casual reading. As such, listserv posts are not structured to have extended “lives” as do blogs. Popular threads allow ideas to be preserved and extended within a listserv conversation, although an initial post does not have a lasting “home” in its original form.

Unlike a blog, there is no primary author of the listserv. Instead, there are thousands of potential authors, many posting, more simply reading or acting as “‘overhearers’ of […] ongoing discussions” (Gruber 22). Helmut Gruber describes the funny nuance of the listserv as follows:

[T]he communicative situation which is referred to by the metaphor “email discussion” might be more accurately compared to the situation of a group of persons who are sitting in a dark cave: Anybody knows that there are some others and that they might (but must not) respond to one's own utterance. The achievement that participants have to accomplish is to formulate an utterance that conforms to a norm that is never discussed overtly. And the risk one runs if he/she does not conform to this norm is simply to get no response and to be excluded from the discussion. (Gruber 22)

Although all listserv participants have equal permissions to participate in the conversation, as Gruber demonstrates, participation beyond “lurking” (Cubbison 375) requires sophisticated understanding of convention on the listserv. Additionally, author status (rank, background, age) complicates the democratic aspects (Matsuda) of this “textually constituted” (Paré, Starke-Meyerring, and McAlpine, “Dissertation” 184) rhetorical community.

In clarifying how genres are necessarily embedded in social interaction, Carolyn Miller carefully defines a rhetorical community as a virtual community, one that is

[inclusive] of sameness and difference, of us and them, of centripetal and centrifugal impulses […] for rhetoric in essence requires both agreement and dissent, shared understandings and novelty, enthymematic premises and contested claims, identification and division (in Burke's terms). In a paradoxical way, a rhetorical community includes the ‘other’. So rather than seeing community as an entity external to rhetoric, I want to see it as internal, as constructed. Rather than seeing it as comfortable and homogeneous and unified, I want to characterize it as fundamentally heterogeneous and contentious. (Rhetorical 74)

The WPA listserv{3}, like many instances of CMC, is nothing if not fundamentally “heterogeneous and contentious.” The dataset that I examine demonstrates this tendency of the community, frequently featuring “agreement and dissent, understanding and novelty,” and, most obviously in meta-genre accounts, “identification” (Miller, Rhetorical 74). Miller’s notion of community works against essentializing concepts of community, instead prioritizing difference. The natural mechanism of CMC, in this particular formulation, is to include ‘the other,’ and not let it be subsumed by convention in macro-level culture. This necessary balance to construct rhetorical community mirrors the balance of tradition and innovation required for genres to live, thrive, and change.

As a rhetorical community, the WPA listserv is a virtual collective that frequently produces meta-generic commentary about the genres that constitute Writing Studies: teaching philosophies, textbooks, syllabi, theories, job postings, budgets, cfps, etc. This meta-generic characteristic of WPA listserv discussions makes it a particularly useful place for apprentice members to learn the community because it both highlights genre conventions and potential for genre change. Although many conventions of academic writing are preserved within the rhetorical community, for instance a reliance on source attribution and Standard Written English, the listserv is also a purposeful departure in many respects, with authors frequently passing along humorous or engaging videos, personal anecdotes, and external blog posts. In this way, the listserv functions as a digital watercooler over which ideas, terms, and disciplinary concepts are discursively constituted, broken down, and built up again. If genres are truly cultural artifacts, as Miller’s 1984 article posits, and as her later work further problematizes, the WPA-l archives are an incredibly wealthy treasure trove.

Transitional Threads and the Life of a Listserv Conversation

The question of the dissertation’s purpose and place in academia circulates in numerous venues outside of university departments, dissertation committees, and award-granting agencies—outside the formal university itself. Ironically, though the dissertation is ubiquitous in academia, it is rarely addressed in research contexts: it is “an under-theorized, under-studied, and under-taught text” (Paré, Starke-Meyerring, McAlpine, Dissertation 179). Perhaps because of this lack, it is a popular topic of discussion in informal academic spaces, such as that of the WPA listserv. The dataset I examine consists of the emails prompted by the post “how long did it take you to finish your dissertation?” The resulting discourse circulated on the WPA listserv for more than a week in various forms, including two transitional threads.

Between 9 January 2012 and 16 January 2012, the week during which these discussions about the dissertation took place, there were 262 total posts. Of these total posts, there were 51individually named threads, 25 of which received no response. Most of the posts that received no response were announcements, such as job advertisements and calls for papers. The average number of posts per day was 32, with a range between 7 total posts, on a Sunday, and 67 total posts, on a Monday. Thread A, titled “how long did it take you to finish your dissertation” had the highest degree of responsiveness{4} (Erickson) that week—meaning that it was the most popular – with 87 total posts. In addition to its immediate interest, Thread A generated the following two transitional threads: “the dissertation is a bogus requirement,” or Thread B, and “how well related was your dissertation to your professional life post PhD,” or Thread C. After Thread A, the next most popular post that week had 29 responses, and the two next most active conversations were Thread B and C, with 18 and 16 posts, respectively. Thus, these three threads constituted 46% of all listerv activity that week.

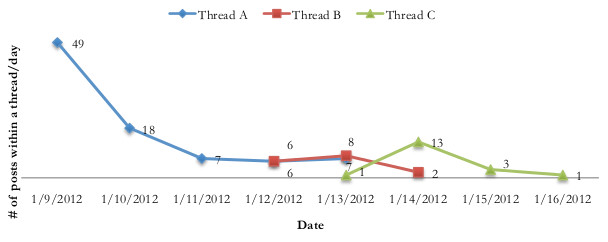

Thread A began 9 January 2012 and concluded 13 January 2012. Thread B ran concurrently with both Thread A and Thread C, beginning on 12 January 2012 at and concluding on 14 January 2012. Thread C, which began after Thread A subsided, but ran concurrently with Thread B, lasted from 13 January 2012 to 16 January 2012. CMC provides such precision and allows us to examine how the conversation develops, ultimately splintering in two different, but related directions, and surviving for eight days in total. Figure 1 shows the lives of these three threads, highlighting their relationship to each other in time.

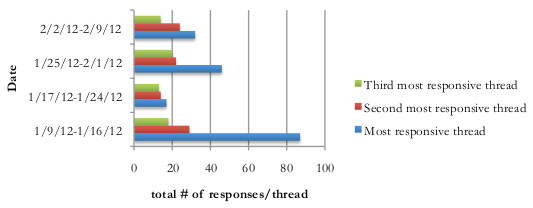

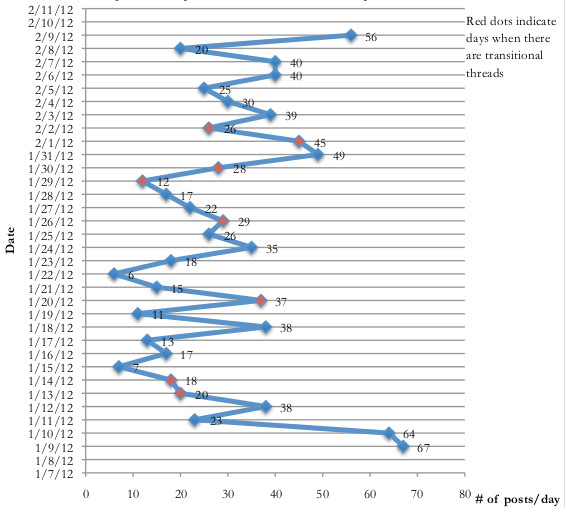

To put this conversation in perspective, consider the listserv activity during the month-long period from 9 January 2012 to 9 February 2012. During that period, there were 951 total posts. In the week following the discourse that constitutes my dataset, 17 January—24 January, there were 181 total posts and 48 independent threads (which includes posts to which no one responds). Of these, the most responsive threads had 17, 14, and 13 responses (see Figure 2), and there was one transitional thread (see Figure 3). From 25 January—1 February there were 223 total posts and 47 total threads. The most responsive threads that week included 46, 22, and 20 posts, respectively. During this week there were four transitional threads. Finally, from 2 February—9 February there were 286 total posts, with 64 independent threads. The most responsive threads had 32, 24, and 14 posts, and there was one transitional thread. Further, in the last 10 years, the dissertation has been named in a thread title on the WPA listserv 317 times, 123 of those occasions, or approximately 40%, were during 2012. All but two of those posts in 2012 were part of the three related threads that constitute my dataset. As Figure 2 demonstrates, in comparison to the rest of the listserv activity in my sample, 87 posts in response to Thread A is notably more responsive than the next most popular thread, which had 46 posts. The 121 total responses that constitute my dataset far surpass the next most popular conversation, 48 responses in two combined threads, which suggests that the dissertation is a contentious topic with wide investment.{5}

Figure 3 indicates response activity from 9 January 2012—9 February 2012, and it highlights dates when transitional threads began; this illustrates the different times transitional threads develop: in the midst of a popular thread on a particularly responsive day in the listserv discourse, or as interest in a particular discussion has waned on less responsive days.{6} Transitional threads are often, though not always, indicated by their title, as in, “Re: getting it (was: “Stop teaching to the test.”),” posted on 26 January. Of course, transitional posts do not always result in successful topic initiation (Gruber), because they may signal that interest in a particular topic is waning. As in the case of, “Re: getting it (was: “Stop teaching to the test.”),” there were only 2 posts in the transitional thread, in contrast to the 46 posts in the original thread. Instead of repeating a former title, sometimes items are dropped from thread titles to suggest a shift in focus, as in “Higher Education and President Obama,” which changed to “Obama and Higher Ed>>-- Accreditation Changes.”

Micro-level Analysis of Transitional Threads

In his examination of academic collectives, Anthony Paré describes how they call upon multiple discursive tools to self-regulate:

In order to guarantee consistency in their rhetorical strategies, collectives establish rules for identifying the appropriate occasions for discourse and the proper conduct of the participants in the discourse […]collectives exert some control over their discourse by reaching (or imposing) agreement on the exigence-situation relationship and genrefying it. Consistency in understanding and responding to conventional rhetorical situations insures communities that their discourse practices will produce the desired social actions. (A87-A88)

Repeated reactions to individual agents’ accounts constitute genre convention on the listserv, thus “genrefying” the discourse. The transitional threads are one particularly sophisticated tool users employ to help manage convention on the listserv, branching off from previous threads when they are no longer directly related to the initial question or appropriate (see Johnson-Eilola and Selber for further discussion of the complexity of determining appropriateness on the listserv) within the thread, given the norms established by the collective.

Just as Thread B begins, in fact, one poster recognizes that his post in Thread A is misplaced since the conversation migrated and there was a more conventional venue for his previous comments. He posits: “Dang, if I’d waited 10 more minutes I’d have posted here [in Thread B] instead… I just made my case for [the dissertation].” Such meta-language demonstrates knowledge of the unstated rhetorical community rules that allow the listerv to function successfully, and it suggests that there is a “right” place for comments in threads. Participation on the listerv depends greatly on kairos and attention: the conversation moves and changes quickly, and posters must be adept at reading the shifts in discussion and meeting the changing interests of the macro-level rhetorical community. Transitional threads help maintain this environment.

Taken together, as a conversation that spans eight days, Threads A, B, and C “add up” to macro-level cultural artifacts and constitute the dissertation construct within the rhetorical community of the listserv. Microanalysis of the transitional threads, or turning points, demonstrates the sometimes contentious nature of the individual speech acts that constitute macro-level interaction. In the discussion that follows, I’ve included the first post in each thread, to examine how and why a thread starts. The first posts in each transitional thread represent an individual speech act; simultaneously, these posts demonstrate the influence of the macro-level culture on micro-level interaction, since they respond to the larger discursive system by changing their titles and self-regulating response. For Thread A, I have also included a conventional response (Herring; Gruber; Johnson-Eilola and Selber; Cubbison), to demonstrate expectation within the thread and to highlight the dissertation meta-genre discussion, which itself oscillates between the extremes, micro-level evidence of the dissertation—in the form of narratives and personal anecdotes, and macro-level evidence—institutional critique and broad-based data. Finally, I include the last post in each thread to theorize why they conclude, and to examine how self-regulation of convention on the listserv functions.

Analysis of Thread A

Below, I examine posts that constitute Thread A in an attempt to provide a snapshot of this thread’s life and examine how the subsequent transitional threads function within the larger discourse. The initial post is reproduced in its entirety below:

1 Inside Higher Ed has an article reporting on discussion about the

2 dissertation in the humanities: http://ow.ly/8mKbi

3 The article leads with the fact that the average student takes 9 years to

4 get the diss finished. That fact didn't hit home for me till I read the next

5 sentence:

6 Richard E. Miller, an English professor at Rutgers University's main campus

7 in New Brunswick, said that the nine-year period means that those finishing

8 dissertations today started them before Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Kindles,

9 iPads or streaming video had been invented.

10 Yeah, in 9 years quite a bit can change. So I'm wondering how long it took

11 some of you to get the diss finished. Do the details in that article ring

12 true for you and the students in your programs?

13 Trudy.

Trudy’s opening move draws the audience outside the post, to a different genre. The statistic that Trudy shares from the article constructs the dissertation as a genre in “crisis,” which in turn garners interest from the listserv. The cultural landmarks of Web 2.0 underscore the problematic nature of the dissertation for Trudy, and, given the clear topical pull of her thread—49 responses in the first day, 87 in Thread A, 121 in the three threads combined—a considerable population of users on the listserv as well. Trudy closes the post by turning the statistic into a request, eliciting meta-genre accounts of the social purpose of the dissertation, dissertation genre convention, and recommendations for dissertation genre change. The thread title, “how long did it take you to finish the dissertation?” is the question to which members of the rhetorical community respond; however, the question itself does not appear in the body of the post. The use of explicit and implicit questioning is a conventional form to initiate listserv discourse (Gruber), and a different form of the question in the thread title versus the body of the post is conventional on the WPA listserv. In the body of the text of this initial post, the question is articulated informally: “Do the details in that article ring true for you and the students in your programs?” The conversational impetus—the ‘cost’ for users to participate, the likelihood they will engage—for answering such personal, micro-level questions about the dissertation may in part account for the high degree of responsiveness for this particular thread.{7}

On 12 January 2012, Arnold responds to Trudy’s question. His response demonstrates convention in this thread, and, importantly, highlights the micro-macro-level tension within dissertation meta-genre accounts. This response was posted 62nd in the chain of response and thus comes just as the conversation begins to shift to a new discussion, and Thread B emerges to capture this new interest. I have selected Arnold’s response to examine for two reasons: 1) this post runs concurrently with Thread B, and such analysis helps explain why two threads are sustained simultaneously; and 2) because Arnold takes time to summarize the previous ideas addressed in the thread it functions as a synopsis of the discussion:

1 I agree with what you're saying here, and I think this perspective is in line with

2 several views offered in this thread in suggesting that there are many reasons why

3 doctoral students take 5 or more years, after their exams, to write their dissertations or

4 just end up ABD. My wife is ABD from her lit phd because she found her committee so

5 difficult to work with and the general culture of the program so toxic. It's sadly not an

6 unfamiliar story.

7 But I think this NSF report and the MLA business is a different issue. This is not about

8 judging students. It's about evaluating programs and perhaps the general culture of

9 English/humanities phds. I would like to be able to meet prospective graduate students,

10 look them in the eye, and say, we will give you a 5-year TA-ship and many of our TAs

11 complete their dissertation in 5 years, so it's reasonable to expect that you can as well.

12 However we define the dissertation, I would argue that it should be a text (in whatever

13 media) that can be reasonably composed in two years by the typical, full-time doctoral

14 candidate. Or more importantly that we might rethink the preparation we give students

15 leading up to their dissertation writing phase, as well as the support network they have

16 while writing. Ultimately these will be local matters though I think we can benefit from a

17 national conversation about what seems to be working.

Like other conventional responses (Herring), Arnold begins with agreement and summary of the argument thus far (lines 1-4). Thus, in his opening, Arnold has already demonstrated his knowledge of the thread’s purpose and general convention on the listerv. However, the body of his post quickly shifts to overt meta-generic commentary –“However we define the dissertation” – recognizing that problems with genre are frequently aligned with a genre’s constraints, and are, thus, mutable. Arnold moves from micro- to macro-level critique of the dissertation genre; however, in concluding his post, he seems caught between these realms. He moves from his own anecdote to an affirmation of a larger systemic problem, but he concludes the discussion by taking accountability away from individuals and micro-level interaction entirely. He argues that it is “not about judging students. It’s about evaluating programs and perhaps the general culture” (lines 7-8), though these problems “must be handled ‘locally’” (line 16). Arnold is swept up in the divide that Miller identifies, that between the micro/macro, individual actors/institutions. This valley between micro-macro troubles responsibility: if it is the institution’s fault and the genre’s fault, and we must not blame individuals, who can do something to alleviate the problem? Where can we do the work?

The last post in Thread A was composed by Frank, on 13 January 2012, four days after the conversation began. His response reflects the tension that concludes Arnold’s conventional post. For such a popular thread, lack of response is significant, and it’s worth comparing the previous two posts to this final one to understand why the discourse shifts to Thread B. I’ve provided an excerpt from Frank’s larger post below (see the full post in Appendix 1):

1 Arnold,

2 Good point, this “top down business” thing, but my point is that what makes for

3 value in academe needs reconsideration. My experience suggests that many good

4 people have been excluded from our clawed-into ranks for reasons that are ultimately

5 harmful to the profession. Oh, I could name names of extraordinary people over the years

6 who bailed because of the hurdles that maintain the insider culture, many times because

7 of the cranky, outmoded requirements of the dissertation, not at all for incapability.

8 It's true, as you say, that the dissertation supports the publish-or-perish fetish of the

9 academic industry, a fetish that seems to generate much more "scholarship" than could

10 ever be usefully digested by any normal human being, even a PhD, much of it perfunctory.

Although Frank demonstrates awareness of convention on the listserv, his assertion that the primary problem with the genre is its “cranky, outmoded requirements” (line 7) repeats an idea that has already taken root in Thread B, i.e. “the dissertation is a bogus requirement.” Posters who might have responded to this comment have moved their discussion to the transitional thread’s more appropriate venue (see Johnson-Eilola and Selber for further discussion of the complexity of determining appropriateness on the listserv). This post strays from the initial purpose of the thread. It clearly does not answer “how long did it take you to finish your dissertation,” and it comes as the responsiveness to the thread has diminished. Because of the self-regulating nature of the rhetorical community of the listserv, this thread concludes with Frank’s response. The community corrects this disruption of convention with silence, a powerful tool in CMC.

Although difficult to measure, perhaps the most problematic characteristic of this post, which might account for the lack of response, is its conversational impetus. Like other suggested topic changes/questions that go unanswered in the discourse, Frank’s suggestion that “what makes for value in academe needs reconsideration” is complex and difficult to answer, much more difficult than responding to the macro-level assertion that “the dissertation is a bogus requirement,” or providing micro-level evidence in the “how long did it take you to finish your dissertation” thread. Frank suggests a turn that would marry these two levels of discourse. Responding to Frank’s post would ask posters to consider both the systemic, structural aspect of the dissertation as well as the individual agents who write dissertations.

Analysis of Thread B

Thread B, unlike the other threads addressed here, is not a question but a declaration. It developed three days after the initial discussion began. It takes as its new thread title a catchy line from Thread A that was repeated by multiple authors, “the dissertation is a bogus requirement.” Correspondingly, responses to the thread are also primarily produced as assertions. The transitional post is included below:

1 I'm changing the thread because the discussion has changed.

2 I wonder, is anybody willing to defend the dissertation? Personally, and

3 maybe eccentrically, I found the year I spent writing my dissertation a

4 challenge and a pleasure, and uniquely valuable. I learned what sustained,

5 rigorous scholarship meant in ways that no seminar paper had taught, and I

6 discovered that I really had the yearning and capacity to produce a

7 book-length study. Does that mean I was fooling myself and just wanted to

8 “belong to the club”? Does that mean scholarly books (not just

9 dissertations) are bogus, too?

The opening line provides recognition of the changing discourse and explains the purpose for the transitional thread. Interestingly, the new thread captures the critique of the dissertation that had begun to characterize the final posts in Thread A, but the author of this post, Randall, disagrees with the shift in discourse. Instead, he invites users to “defend the dissertation,” which he proceeds to do as well. Randall’s creation of this transitional post is striking because he helps to maintain the consistency of individual threads without forwarding his particular beliefs about the dissertation in the title. Such strict observance of convention and participation in regulating the listserv is a testament to the powerful nature of the unstated rules of rhetorical communities.

Thread B spans three days, two that overlap with the last two days of Thread A, and two that overlap with Thread C. Thread B elicits meta-genre accounts of the dissertation that argue whether or not the dissertation is indeed a “bogus requirement.” Most posts, like the first, do not have a greeting and are not specifically addressed to anyone on the listserv. Instead, they address macro-level considerations of the dissertation genre. The last post in Thread B, breaks with these conventions:

1 [previous author]: It is interesting.

2 My dissertation writing group was four of us, all in different disciplines (comp,

3 obviously; an anthropologist writing up some fieldwork she'd done in Brazil; a social

4 psychologist studying incidents of spousal abuse report rates in relation to high profile

5 news items of various kinds; and a mass media study analyzing coverage of activist

6 campaigns). Our group actually made it a policy not to share chapters or large blocks of

7 text because we didn't want to spend lots of time and energy explaining our disciplinary

8 apparatus to each other, but we did talk about our work during dinner breaks. The

9 expectations for publishability, 'finishedness,' and so on were wildly different. Our

10 psychology student needed the diss to produce (and hence to look like) 3 pretty

11 immediately publishable articles. The anthropologist already had a contract to publish her

12 book, so she was writing for her editors and her committee was OK with that. Of course,

13 I graduated 9+ years ago, quite a while before she did, and I don't believe the book has

14 ever been published. But that's another story.

As in the final post from Thread A, Steven’s response veers fairly significantly from the initial question posted. Further, this post closely resembles the discourse concurrently taking place in Thread C. Thread C features narrative, personal details about dissertation process and disciplinarity. On the other hand, Thread B’s conventional posts addressed macro-level issues regarding the dissertation—program critiques, institutional analysis, and attention to the dissertation as a mechanism within the university. However, by the third day, the degree of responsiveness had dropped off, and Thread B was forced to compete for readers and posters with Thread C. The interest in the initial post receded, and the conversational impetus that Thread C introduces overtakes Thread B. This thread behavior suggests that transitional threads can be indicative of different motives: to reign in a conversational direction, to reignite interest in a waning conversation, or to more accurately capture a shifting discussion. It also suggests that the initial post in a thread drives specific convention within a thread, and participants must pay attention to such nuance for successful participation.

Analysis of Thread C

On January 13, four days after the discussion began, Meredith posted her eleventh response within the larger conversation, offering a new question for the group: “How well related was your dissertation to your professional life post PhD?” As a frequent contributor to Thread A, Meredith seems to have taken stock of the fact that the conversation has waned, but those still interested have begun orienting their discussion in a new direction. Meredith captures this apparent new interest by posting the comment below:

1 What you've said brings up something I've long been a bit curious about. I wonder how

2 many of us have written anything in our dissertations even remotely connected to the

3 work we end up doing in our jobs post PhD. Connected to that is the question of whether

4 we were “allowed” to choose our own topic or given a topic by our committee, or some

5 portion thereof.

Unlike Thread B’s transitional post, in which the author explains the reason for the change in title, Meredith simply retitles the thread and references previous discussions as a way to connect this thread with the macro-level discourse. Like Randall, Meredith responds to critiques of the dissertation, but she offers an alternative to the macro-level discussion of the dissertation featured in Thread B. Returning to the title format in Thread A, her question asks posters to make micro-level, personal, practical connection between dissertation work and professional work. Like the other initial posts, the thread title is not written in the post itself. In this thread posters offer personal narratives, and most authors in this thread are veterans of the field and frequent listserv users. In contrast to the other threads, most posts in Thread C begin with a greeting that mentions the previous poster by name.

The final post in Thread C concludes this eight-day discussion on the listserv. This post is fairly long, so I’ve included the beginning and end of the post and provide the entire text in Appendix 2:

1 My dissertation […] was about postmodern constructions of the classical idea of ethos,

2 more broadly self-representation in writing, specifically student writing. I was much

3 engaged by the question of how a writer could, given the problems of the originary self

4 being debated at the time, construct an authentic voice or persona (not the same, I know,

5 and began to know through the diss work) in a piece of writing. My own pedagogy at the

6 time, and even still, reacted against a lot of “personal” writing in first year composition and

7 focus on “finding your 'voice' in writing”. I'm still leery of that as a goal for first year

8 writing.

[…]

9 In my position now (I had a five-year hiatus from full time work following a career move

10 for my husband), it's not really clear to me what the scholarship expectations are or

11 whether I will take up a scholarly agenda (instead, I've published a third collection of

12 poetry). It is clear, though, that my pedagogy was absolutely defined by my dissertation

13 work and that it has continued to be the solid ground on which to base my practice of

14 teaching writing.

Unlike previous posts in the thread, this does not begin with a direct reference to a previous author. Instead, the author immediately discusses the content of her dissertation (lines 1-5) without summary of previous discourse or references to other posters or colleagues. Instead of directly answering the original question, Laney complicates the question, expanding the notion of what “professional life post phd” entails. Although Laney’s dissertation was not directly linked to her post graduate scholarship, it has continued to be relevant to her pedagogy. Laney’s post encourages adding further nuance to the notion of “professional life post phd,” complicating the notion of what a dissertation “should” do for graduates.

Ostensibly, a thread like Thread C could go on forever, with each new poster inviting someone else to share a narrative. One post actually begins, “Oh [author], thanks for inviting some of us golden oldies out of the woodwork.” However, Laney’s response is entirely self-referential, void of embedded invitations or references to friends or colleagues. Thus, it bucks general convention within this thread, and like the final posts in Thread A and B, this post ups the conversational impetus for subsequent posters. David Elias and Deborah Brown note that listserv discourse frequently suffers from this lack of interest to participate as discussions become complex; they posit: “e-mail at its non-best also lends itself to a shallow treatment of issues, especially if there are several threads running simultaneously that people want to respond to, leading to a reply-and-run syndrome that does not encourage critical reflection or critical discourse.” Transitional threads periodically seem to stem this tendency, but only for so long.

Like Thread B, which also develops from Frank’s suggestion that the “dissertation is a bogus requirement,” Thread C addresses whether or not the dissertation is successful in the social purpose that Thread A ultimately identifies: to prepare graduate students for professional work. Both transitional threads take up the same question, but they provide different formulations for the discussion, and they operate on different levels. In regard to interaction on the listerv, the conversational impetus to retitle a thread is great, so the fact of these two transitional threads is a testament to the self-regulating nature of the listserv—an acknowledgement of the impact of macro-level discourse on individual posts.

In terms of the dissertation genre, the lives of these posts tell a different story. They conclude without resolution, as is frequently the nature of listserv discourse (Elias and Brown). Each thread ends with a post that attempts to reconcile micro and macro-level perspectives of the dissertation genre: to complicate our notions of the social act it is meant to accomplish. However, the fact that such posts are met with silence suggests discursive boundaries on the listserv that seem to prevent resolution of problems of genre. The transitional threads seem to bring us closer to potential answers by essentially editing the discourse to maintain coherent strands, but responsiveness wanes as conversations extend.

Conclusion: Navigating the Micro-Macro Divide

Meta-genre is a rich repository for which to examine genre and its role within a community. As Giltrow notes, meta-genre accounts are not “incidental or amateur, or even […] accurate or inaccurate, but […] a complex indication of social context” (Meta-genre 187). The WPA listserv, a space that largely features naturally-occurring meta-generic discourse, allows us to examine how the rhetorical community constitutes the dissertation and how it might fit into the larger context of Writing Studies and higher education.

Transitional threads are a sophisticated means for self-regulation on the WPA listserv, and the fact of their creation defies some observations about CMC, which suggest that writers generally do not attempt moves that go beyond a certain activity threshold (Erickson; Elias and Brown). Authoring a transitional thread is an active move, representative of complex negotiation within a rhetorical community. CMC provides a literal rendering, tracing the relationship between micro- and macro-level interaction. At once we see both the individual and the set, and the linkage between them. Transitional threads are a marker of the space between these realms, both a product of this relationship and an ongoing part of the process of this relationship. Although much of the discussion about the dissertation in meta-genre accounts lives in the extremes, both structurally and discursively, the transitional threads live in the liminal space between.

Within dissertation meta-genre accounts posted on the WPA listserv, there is a divide between those who think that the dissertation does not accomplish its social purpose and those who are eager to provide examples to prove its validity. These accounts demonstrate multiple constructions of the dissertation’s purpose: to prepare graduate students for professional lives; to create an understanding of the need for and depth of sustained, scholarly engagement; and to act as a gate-keeping measure. Although there is relative consensus regarding these versions of the dissertation as genre and the need for genre change, posters seem torn about how to approach genre change—as Arnold notes, “it’s not about judging students. It's about evaluating programs and perhaps the general culture of English/humanities phds,” though “[u]ltimately these will be local matters.” Arnold’s dilemma demonstrates that members of the WPA listserv rhetorical community are conscious of the tension between the macro- and micro-levels. Individual posts and larger threads alternate between the two realms with frustration because of a perceived powerlessnes to act on an individual level in the face of macro-level systems.

Thus, this conversation effectively captures the problem of the dissertation as a genre, alerting members of the community to its evolving status in terms of social purpose and the constructed nature of the genre. But it should also underscore that problems of genre are not fixed. Meta-generic commentary can be a marker of genre change, and such discourse on the listserv should be seen as such. The perceived powerlessness of some on the listserv and the fact that threads frequently end as outside action is suggested undercut the potential of a rhetorical community such as that of the WPA listserv. Further, just as posts take members outside of the rhetorical community through hyperlinks and citations, and posts elicit specific action, such as applying for jobs and submitting proposals, the ideas and discourse introduced in meta-genre also leak into other genres and communities. This is not a closed community. Posters inevitably carry these attempts to redefine the dissertation outside of the rhetorical community of the WPA listserv, into other communities, into programs, into advising meetings with dissertators, into job talks—into the genres that constitute their workplace and exert force on dissertation genre change. Though challenging, it is worth tracing these networks to further demonstrate what listserv meta-genre accounts do for genre.

The danger in the micro-macro divide, at least in the venue of this WPA listserv conversation, is the tendency to alternate between micro/macro, individual/institutional, specific account/generic activity modes as opposed to spending time in the liminal space in between where individuals and artifacts interact with each other. The danger is to not see this relationship as CMC lays it bare—as a continuum where individual speech acts are directly related to the macro-level culture and are individually powerful because of their role in the group. The challenge, then, is for individuals to have this structural vision of how the micro- and macro-levels are connected in mind. Then, perhaps, this in-between space is where discourse translates into action outside of the listserv.{8}

CMC reveals how individuals do not get lost within collectives. Instead, CMC preserves a record of the heterogeneity and disagreement that takes place within a rhetorical community. The disparate artifacts, developed by diverse individuals, produce and are produced by the genres they enact. Further, Discourse Analysis of CMC reveals how power exists only in interaction, so upon reflection, actors and their associated micro-level discourses are the only potential sites for encouraging genre change. The listserv can and should be a place to foster systematic discussion that confronts the problem of the dissertation within Writing Studies at the level of genre. The challenge is for individuals to confront the middle space and recognize how micro-level interaction ultimately reorganizes macro-level structures.

Appendices

Appendix 1

1 Arnold,

2 Good point, this "top down business" thing, but my point is that what makes for

3 value in academe needs reconsideration. My experience suggests that many good

4 people have been excluded from our clawed-into ranks for reasons that are ultimately

5 harmful to the profession. Oh, I could name names of extraordinary people over the years

6 who bailed because of the hurdles that maintain the insider culture, many times because

7 of the cranky, outmoded requirements of the dissertation, not at all for incapability.

8 It's true, as you say, that the dissertation supports the publish-or-perish fetish of the

9 academic industry, a fetish that seems to generate much more “scholarship” than could

10 ever be usefully digested by any normal human being, even a PhD, much of it perfunctory.

11 Of course, publishing does support the publishers, who make money from the

12 contributed, unpaid work of scholars who find their reward in the promotion and tenure

13 system of the university. Somehow, I keep thinking of the the 17th century triangular

14 mercantile system, in which slaves were circulated for grain and tobacco, etc. If we're

15 going to contribute our scholarship, sometimes wrenchingly obtained, for free, why make

16 massively corporate publishers the beneficiaries? Academic libraries are, of course,

17 complicit, because they have to buy academic periodicals at outrageously pumped up

18 prices. Messy business, all around.

19 The idea that dissertations prepare our graduate students for a subsequent compliance to

20 commercial publishers seems a bit like training the little folk for dancing on demand.

Appendix 2

1 My dissertation […] was about postmodern constructions of the classical idea of ethos,

2 more broadly self-representation in writing, specifically student writing. I was much

3 engaged by the question of how a writer could, given the problems of the originary self

4 being debated at the time, construct an authentic voice or persona (not the same, I know,

5 and began to know through the diss work) in a piece of writing. My own pedagogy at the

6 time, and even still, reacted against a lot of “personal” writing in first year composition and

7 focus on “finding your ‘voice’ in writing”. I'm still leery of that as a goal for first year

8 writing.

9 That interest, I think came in part clearly out of the context of rhet/comp scholarship in

10 the late 80s, early 90s (for instance, Faigley’s Fragments of Rationality, WAC and social

11 construction of knowledge theory, other key edited collections on postmodern

12 subjectivities: Gere, Harkin and Schilb) but may as much have come out of my own

13 beginnings (and, as it's turned out finally) self-identification as chiefly a creative writer. It’s

14 all about persona, all the time, everything! Writing is a way, primarily, to escape your own,

15 terrible self even as your writing, is, finally, chained to it.

16 The diss. work itself was a hugely practical exercise that, as as a 27-29 year old (I think age

17 and circumstance does mitigate the experience and value of the dissertation), truly

18 developed my “stamina” as a writer, researcher, and editor. The experience was made

19 more beneficial by the guidance of an incredibly smart and pragmatic director (high-fives

20 to Debra Journet!) who managed, as well, to advised patiently as I also had two babies and

21 moved across the country.

22 More than the ways in which my diss. influenced my subsequent scholarship, I think, it has

23 shaped and continues to shape my pedagogy. My first appointment included directing a

24 writing center (as part of my faculty weightload), something about which I knew nothing,

25 but learned by doing and with the help of the W-Center e-community. The position was

26 for a composition generalist and I don’t think the committee really cared what my

27 dissertation had been about as long as I would, god, please, help them with composition.

28 In my position now (I had a five-year hiatus from full time work following a career move

29 for my husband), it’s not really clear to me what the scholarship expectations are or

30 whether I will take up a scholarly agenda (instead, I’ve published a third collection of

31 poetry). It is clear, though, that my pedagogy was absolutely defined by my dissertation

32 work and that it has continued to be the solid ground on which to base my practice of

33 teaching writing.

Notes

- According to Web of Science, this article has been cited 435 times. (Return to text.)

- I use discourse analysis in the tradition of language and social interaction (Bartesaghi, Haspell and Tracy). (Return to text.)

- Although the WPA listserv has a title that focuses its purpose, many scholars in Writing Studies contribute to the discussion, and the posts are frequently broader than the immediate concerns of Writing Program Administrators. (Return to text.)

- To address discussion on the listserv, I borrow from Tom Erickson’s framework for analyzing CMC. Erickson is particularly interested in “degree[s] of responsiveness,” or community participation, in CMC. Responsiveness is measurable in the context of listserv responses, both in terms of response quantity and response length. However, the reason that there is such a high degree of responsiveness for some responses and not others is a bit harder to discern, and this concern is not the focus of Erickson’s work. In examining the online conversational genres that constitute the genre ecology of his workplace, Erickson identifies three “ecological properties”: “global pull,” which describes what drives users to the system generally; “topical pull,” which describes how particular conversations engage users; and “conversational impetus,” which describes how likely a user is to stay engaged with a particular conversation based on context. (Return to text.)

- It is also important to note that users engage with the conversations on the WPA listerv differently because of the method with which they receive messages. Of the 3,957 WPA listerv subscribers (in 2014), roughly a quarter receive posts once a day in “digest” form (Barry Maid, personal communication). So, only a quarter of subscribers see the data aggregated as Figure 1 does; the majority of users receive messages as they are composed. Receiving the listserv posts in digest form means that a reader will see threads after they’ve accumulated responses, so they have the same information users would be able to access through the archives, and users immediately know the degrees of responsiveness for each thread before reading within the digest. Though the digest version of listserv posts includes accumulated threads, and they may be read as coherent conversations, this is not how posts are initially experienced. Further, as Laurie Cubbison notes, receiving the digest version of listserv discourse may frustrate active participation: “Though making a list’s volume more manageable, digesting may also force readers into a lurking position. A thread may have erupted, climaxed, and resolved by the time the reader has checked email and read the digest. As a result, digest readers seldom respond to a digested list in writing. Digest readers of very active lists soon realize that the decision to digest may marginalize them in relation to the group’s discourse” (375). If they receive the posts as individual emails, post authors are immediately obvious, unlike those who receive the digest version of the WPA-listserv. All of these variables suggest the nonlinear chain of response and the complex nature of the accumulated listserv thread, and much of this complexity (though certainly not all) is recoverable because of the breadcrumb path CMC provides. (Return to text.)

- Though responsive days on the listserv are not directly aligned with most responsive threads, since thread responsivity is often divided over multiple days, the two are closely related. (Return to text.)

- Although Trudy’s question has serious institutional implications for dissertations in the humanities, and this is a highly academic musing, her tone and diction (in particular, lines 10-11) belie this fact. In this brief request for information, the author begins her sentence with an interjection, uses contractions, and refers casually to “the diss.” This highly stylized mix of formal, informal, casual, and academic requires sophisticated genre knowledge, and successful discussion on the listserv helps solidify membership within the rhetorical community. This stylized tone is especially difficult for apprentice members to approximate. In fact, apprentice members frequently confess to reading the listserv before contributing; for instance, consider the preface to a thread regarding ESL administration: “Hi Folks, I've been lurking on the list for a little while, and this is my first time posting.” In contrast, Trudy’s appropriate tone and her casual approach to a formal request for evidence-based perspectives suggests her comfort within the space. For long conversations, such as this one, participation also requires attention, as indicated by prefaces such as the following, which preceded a conventional, Wednesday evening comment: “I’ve read so scantly in this fascinating thread that I’m hesitant to throw in an observation.” (Return to text.)

- For instance, on September 30, 2013, a post entitled “Homophobia and the CCCC convention” began a discussion that included 39 posts in four related threads. After discussing unequal legislation in Indiana over the listerv, there was uptake (Freadman) outside of this community—the issue carried into different genres and communities. Months later, the issue was raised again on the listerv to report on steps made by “the Queer Caucus and Committee on LGBTQ Issues in response to the important discussion about what it means for CCCC to take place in Indianapolis this year.” These responses included the creation of pins to “demonstrate opposition to anti-queer legislation” and a special featured session. Uptake of the listerv discussion translated to progressive action that, once accomplished, again returned to the listerv. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Bartesaghi, Mariaelena. How the Therapist Does Authority: Six Strategies for Substituting Client Accounts in the Session. Communication & Medicine 6.1 (2009): 15-25. Print.

Bazerman, Charles. Shaping Written Knowledge: The Genre and Activity of the Experimental Article in Science. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988. Print.

Berkenkotter, Carol, and Thomas Huckin. Genre Knowledge in Disciplinary Communication: Cognition/ Culture/ Power. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. 1995. Print.

Berman, Russell A. Reforming Doctoral Programs. MLA Newsletter 43.3 (2011): 2. Web. 23 January 2012.

Council of Graduate Schools. Ph.D. Completion and Attrition: Policy, Numbers, Leadership, and Next Steps. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools. 2004. Web. May 2012.

Council of Graduate Schools. Ph.D. Completion and Attrition: Analysis of Baseline Program Data from the Ph.D. Completion Project. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools. 2008. Web. May 2012.

Cubbison, Laurie. Configuring Listserv, Configuring Discourse. Computers and Composition 16.3 (1999): 371-381. Print.

Elias, David and Deborah Brown. Critical Discourse In A Student Listserv: Collaboration, Conflict, And Electronic Multivocality. Kairos: A Journal for Teachers of Writing in Webbed Environments 6.1 (2001): 2014. Web. August 2014.

Erickson, Thomas. Making Sense of Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC): Conversations as Genres, CMC Systems as Genre Ecologies. In the Proceedings of the Thirty-Third Hawaii International Conference Systems Science, 2000. Web. March 2014.

Devitt, Amy. Intertextuality in Tax Accounting: Generic, Referential, and Functional. In Textual Dynamics of the Professions: Historical and Contemporary Studies of Writing in Professional Communities. Eds. Charles Bazerman and James Paradis. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991. 336-357. Print.

Freadman, Anne. Uptake. The Rhetoric and Ideology of Genre: Strategies for Stability and Change. Eds. Richard Coe, Lorelei Lingard, and Tatiana Teslenko. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton UP, 2002. 39–53. Print.

Giltrow, Janet. Legends of the Center: System, Self, and Linguistic Conscious- ness. Writing Selves/Writing Societies. Ed. Charles Bazerman and David Russell. Web. August 2012.

---.. Meta-Genre. The Rhetoric and Ideology of Genre: Strategies for Stability and Change. Eds. Richard Coe, Lorelei Lingard, and Tatiana Teslenko. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton, 2002. 187-205. Print.

Giltrow and Stein. Genres in the Internet: Innovation, Evolution, and Genre Theory. Genre in the Internet. Eds. Janet Giltrow and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 2009. 85-109. Print.

Golde, Chris M. and Dore, Timothy M. At Cross Purposes: What the Experiences of Doctoral Students Reveal about Doctoral Education. Philadelphia: A Report for the Pew Charitable Trusts, 2001. Web. Jan. 2012.

---.. The Survey of Doctoral Education and Career Preparation: The Importance of Disciplinary Contexts. Path to the Professoriate: Strategies for Enriching the Preparation of Future Faculty. Eds. Donald H. Wulff, and Ann E. Austin. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004. Print.

Grafton, Kathryn. Situating the Public Social Actions of Blog Posts. Genre in the Internet. Eds. Janet Giltrow and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 2009. 1-26. Print.

Gruber, Helmut. Computer-Mediated Communication And Scholarly Discourse: Forms Of Topic-Initiated And Thematic Development. Pragmatics 08.1 (2001): 21-45. Print.

Herring, Susan. Computer-Mediate Discourse Analysis: An Approach to Researching Online Behavior. Designing for Virtual Communities in the Service of Learning. Eds. Sasha Barab, Robert Kling, and James H. Gray. Cambridge University Press. 2004. Web. August 2014.

---. Interactional Coherence in CMC. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 4:4, 1999. Web. August 2014.

---. Two Variants of an Electronic Message Schema. Computer-Mediated Communication. Ed. Susan Herring. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 89-109. Print.

Herring, Susan et al. Weblogs as a Bridging Genre. Information, Technology & People 18(2): 2004. Web. March 2014.

Johndan Johnson-Eilola and Stuart A. Selber. Policing Ourselves: Defining The Boundaries Of Appropriate Discussion In Online Forums. Computers and Composition 13.3 (1996): 269-291. Print.

Knorr-Cetina, Karin and Aaron Victor Cicourel. Advances in Social Theory and Methodology: Toward an Integration of Micro and Macro- Sociologies. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1981. Print.

Matsuda, Paul Kei. Negotiation of identity and power in a Japanese online discourse community. Computers and Composition 19.1 (2002): 39-55. Print.

Maurer, Elizabeth. Working Consensus and the Rhetorical Situation. Genre in the Internet. Eds. Janet Giltrow and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 2009. 113-142. Print.

Miller, Carolyn. Genre as Social Action. Quarterly Journal of Speech 70 (1984): 151- 167. Print.

---. Rhetorical Community: The Cultural Basis of Genre. Genre and the New Rhetoric. Eds. Aviva Freedman and Peter Medway. London: Taylor and Francis, 1994. 67–78.

Miller, Carolyn and Dawn Shepherd. Questions for Genre Theory from the Blogosphere, Genre in the Internet. Eds. Janet Giltrow and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 2009. 263-290. Print.

---. Blogging as Social Action: A Genre Analysis of the Weblog. Into the Blogosphere: Rhetoric, Community, and Culture of Weblogs. Eds. Laura Gurak, Smiljana Antonijevic, Laurie Johnson, Clancy Ratliff, and Jessica Reyman. University of Minnesota Libraries, 2004. Web.

Orlikowski, Wanda J. and JoAnne Yates. Genre Repertoire: Examining the Structuring of Communicative Practices in Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 39 (1994): 541-574. Print.

Paré, Anthony. Rhetorical Genre Theory and Academic Writing. Journal of Academic Language and Learning 8.1 (2014): 83-94. Print.

Paré, Anthony, Doreen Starke-Meyerring and Lynn McAlpine. The Dissertation as Multi-genre: Many Readers, Many Readings. Genre in a Changing World. Eds. Charles Bazerman, D.Figueiredo, and A. Bonini. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2009. Web. Jan. 2012.

Starke-Meyerring, Doreen, Anthony Paré, King Yan Sun, and Nazih El-Bezre. Probing Normalized Institutional Discourses About Writing: The Case of the Doctoral Thesis. Journal of Academic Language and Learning 8.2(2014): A13-A27. Print.

Swales, John. Research Genres: Exploration and Application. New York: Cambridge UP, 2004. Print.

Tracy, Karen and David Haspel. Language and social interaction: Its institutional identity, intellectual landscape, and discipline-shifting agenda. Journal of Communication, 54(2004): 788-816. Print.

Metagenre on the WPA-L from Composition Forum 31 (Spring 2015)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/31/metagenre.php

© Copyright 2015 Kate Pantelides.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 31 table of contents.