Composition Forum 31, Spring 2015

http://compositionforum.com/issue/31/

The Development of Disciplinary Expertise: An EAP and RGS-informed Approach to the Teaching and Learning of Genre at George Mason University

Abstract: In the U.S., international enrollment trends have increased the pedagogical imperative to address multilingual graduate student writers’ linguistic needs/growth in the process of their developing disciplinary expertise. In the context of this internationalization effort, what can two disciplines—Applied Linguistics and Composition—constructively offer in terms of a pedagogical approach to address such growing institutional demands? With regard to the various ways in which these disciplines approach the teaching and learning of disciplinary expertise, what might a research-informed English for Academic Purposes (EAP)/Rhetorical Genre Studies (RGS) curriculum arc look like and how might multilingual graduate writers respond to such an integrated pedagogical trajectory? Further, to what extent might such a curriculum be able to balance evolving student needs and institutional expectations for students’ linguistic development? This program profile examines the potential of Tardy’s 2009 model for building genre knowledge among a specific student population: first-year multilingual international graduate students enrolled in a "bridge" program at George Mason University. In addition to describing the practical work of enacting Tardy’s model at the program and course levels, the authors detail the results of a related study aimed at exploring students’ development of genre knowledge over the course of the bridge year. Results point to the complexity of designing and implementing an EAP/RGS-informed course structure which values the intersectional nature of disciplinary knowledge development and suggest the need for such an approach to explicitly foreground the visibility of language teaching, learning, and assessment in order to ease student anxiety around both language and genre development.

Introduction

A 2011 survey of colleges and universities in the United States found that 84% of U.S. institutions of higher education perceived a growth in internationalization efforts at their institutions in the last three years (ACE). Within university academic programs in particular, this move toward internationalization has led to a substantial and steady increase in both undergraduate and graduate international student enrollments. For example, in the 2012-2013 academic year alone, according to the Institute of International Education, 724,725 international students studied in the United States, including 165,978 graduate Master’s students, an 8% increase of Master’s level students from the previous year (Open Doors).

These trends in internationalization are supported by a larger global marketplace where the value of U.S. higher education is consistently calculated by prospective students and their financial supporters and where individual U.S. institutions work hard to gain brand recognition in order to attract and recruit international students. On the U.S. side, university administrators are often motivated to internationalize the campus because of the economic, political, and academic benefits of internationalization initiatives. Put simply, internationalization provides one strategy for fostering financial, political, and intellectual health on campus. In fact, in some cases, the number of international students on campus is increasingly being used to judge institutional effectiveness (Douglas). Additionally, a high level of university internationalization has been found to correlate positively with economic performance (Maringe and Gibbs). Finally, in terms of intellectual and experiential expectations for students, many argue that campus internationalization may lead to more sophisticated multicultural and global competencies for all graduates (Bevis and Lucas).

And yet, while such large-scale financial, political and intellectual outcomes are worthwhile and significant, the pathways available to U.S. administrators and faculty for achieving such goals on the ground are less certain, shifting and expanding as the international enrollments grow and diversify. In this dynamic context of internationalization, a particularly rich environment for writing program development and evaluation emerges as the changing student body leads administrators and faculty alike to consider new approaches to instruction. All are asked to think strategically—pedagogically and administratively—about how best to meet international and multilingual student needs. To address these demands, some are encouraging greater flexibility and innovation with regard to curriculum development/design, instruction, and assessments. For, as Foskett points out, if U.S. internationalization initiatives are to succeed beyond the recruitment process, a comprehensive campus structure should be put in place and adequately supported. This type of transformative internationalization “is not simply about recruiting students from other countries, but is about changing the nature, perspective and culture of all the functions of the university. Internationalization reaches to the heart of the very meaning of 'university' and into every facet of its operation, from teaching and education to research and scholarship, to enterprise and innovation and to the culture and ethos of the institution” (37).

In this context, writing program developers, in particular, are tasked with enacting theoretically sound, pedagogically creative approaches to writing in the disciplines that will respond to the needs and capitalize on the strengths/contributions of international, multilingual graduate writers. This article presents a program profile and research study of one such graduate level writing intervention, Provost 506/507: Graduate Communication Across the Disciplines (hereafter PROV 506/507), informed by Tardy's 2009 model for building students' genre knowledge and designed to move first-year multilingual graduate students along a curriculum arc that integrates English for Academic Purposes (EAP)- and Rhetorical Genre Studies (RGS) -informed pedagogies with the aim of developing emerging international scholars. To this end, we present a detailed description of the program and the course-level intervention, with particular focus on the context of internationalization that both benefits and constricts the course design. In addition to describing the practical work of enacting Tardy's model, the authors detail the results of a study aimed at exploring enrolled students' development of genre knowledge{1} over the course of a year. Utilizing Cultural Historical Activity Theory to analyze the locus of a perceived tension among enrolled students and intervention course instructors with regard to the development of disciplinary expertise, the study points to the complexity of designing and implementing an EAP/RGS-informed course structure which values the intersectional nature of disciplinary knowledge development and suggests the need for such an approach to explicitly foreground the visibility of language teaching, learning, and assessment in order to ease student anxiety around both language and genre development.

Program Profile: George Mason University, Graduate BRIDGE Pathway

History, Context, and Goals

In an effort to capture greater international enrollments at both undergraduate and graduate levels, George Mason University (after, Mason) launched a new initiative, The Center for International Student Access (CISA), in 2010. Designed to attract academically admissible international students who fell just short of the required overall Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) entrance score and administered through the Provost Office, CISA began offering the undergraduate pathway program, ACCESS, in 2010 and the graduate pathway program, BRIDGE, in 2011.

The CISA BRIDGE program was responsive to university expectations for international multilingual graduate students, fostering a three-pronged approach to student success focused on students’ academic, cultural, and linguistic development. Key Mason constituents felt that large numbers of potential international Master’s level students were deterred by Mason’s high entrance TOEFL© requirement;{2} therefore, the BRIDGE program was meant to capture these students by providing sufficient additional English language development to enable these students to achieve a program-determined proficiency level. To this end, with regard to institutional language policy, it was determined that the BRIDGE program would be one year in length in order to give enrolled students reasonable and necessary time to develop language proficiencies across linguistic domains.{3}

Beyond language considerations, two other critical decisions were made with regard to student enrollment in and progression beyond BRIDGE. First, it was determined that all BRIDGE students would be provisionally admitted to both BRIDGE and their graduate programs concurrently; as a result, all BRIDGE students were able to fully participate in their graduate programs from the start (e.g. disciplinary coursework, departmental advising, graduate unit networking, research, etc.). Unlike other pathway program models, therefore, BRIDGE students were not concerned about applying to their graduate programs during the BRIDGE year since they had already been provisionally admitted. The second decision was to set the general BRIDGE program coursework (see Table 1).{4}

|

|

|

|---|---|

| Fall Term | Spring Term |

| Graduate Study Preparation for International Students (2 credits) | Graduate Study Preparation for International Students (2 credits) |

| Graduate Communication Across the Disciplines I (4 credits) | Graduate Communication Across the Disciplines II (4 credits) |

One or more of the following English developmental courses may be required based ons tudent mid-year assessment:

|

|

| One required course toward Graduate Program (3 credits) | One or two required courses for the Graduate Program (3-6 credits) |

| Total Credits: 11 | Total Credits: 10-12 |

Table 1. BRIDGE Program Curriculum

Once this general set of BRIDGE program policies and the program-level curricular arc had been established by CISA program administrators, the second level of program creation began, centering on course design. In that context, two of the authors, Anna Habib and Karyn Mallett, were selected and given the summer months to design PROV 506/507. Each collaborator brought a different set of contributing expertise with regard to writing in the disciplines and working with international multilingual students. Specifically, Anna came to the course as a multilingual Term Assistant Professor in the English Department, having taught first-year composition and third-year writing in the disciplines courses for several years at Mason. Karyn came to the course development project with a Ph.D. in Second Language Studies/Applied Linguistics, had taught English as a Second Language (ESL) as well as first year composition for over ten years, and was relatively new to Mason in the joint position of Assistant Director, English Language Institute (Mason’s intensive English program) and Assistant Director for Language Development, CISA.

In this context and for this particular BRIDGE student population, the year-long eight-credit intervention course, PROV 506/507, was created. Early on in this stage of the BRIDGE program building process—the course design phase—an important decision was made: namely, informed by theoretical principles, the course creators proposed and the CISA program director approved a collaborative instruction model so that each section of PROV 506/507 would be co-taught by a composition specialist and an EAP language specialist. With this approval in place, Anna and Karyn worked to build out both macro- and micro-level course elements, attempting to meaningfully infuse English language teaching/learning into a genre-based curriculum.

Tardy’s Theoretical Model and the Development of an EAP/RGS-informed Pedagogical Approach

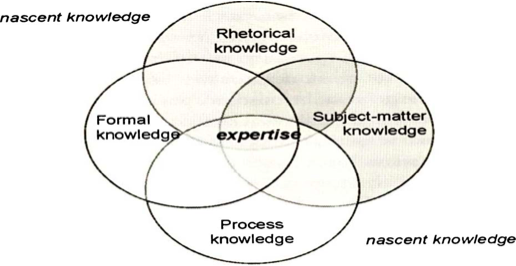

In an effort to provide students with a theoretically informed course structure, the course designers explicitly took Tardy’s reformulation of Beaufort’s domains for developing disciplinary expertise as a starting point in course creation, aiming to account for the experiences of multilingual students in building genre knowledge. In her 2009 work, Tardy defines genres as “social actions that are used within specialized communities; that contain traces of prior texts in their shape, content, and ideology; and that are networked with other genres in various ways that influence their production and reception” (20). As part of this definition of genre, she locates expert genre knowledge at the convergence of four domains of knowledge (see Figure 1): formal, process, rhetorical, and subject-matter knowledge. Formal knowledge includes structural as well as lexico-grammatical textual conventions, including “knowledge of linguistic code” (21). Process knowledge describes the means through which a genre is enacted, including both the composition of particular texts as well as the understanding of how genres interact in larger networks and systems. The domain of rhetorical knowledge describes a socio-rhetorical understanding of genre, including the ways that texts work for various purposes, in different contexts, within particular power structures. Finally, Tardy describes subject-matter knowledge as familiarity with relevant content within a particular discipline. Genre expertise, then, is located at the intersection of these domains; students’ ability to move within their disciplines is predicated on an understanding of all of these domains.

Figure 1. Tardy’s Four Domains of Genre Knowledge (from Building Genre Knowledge (Tardy 22)

As a result of her case studies, Tardy identified a number of strategies and resources graduate students use to build this type genre expertise, including:

- Prior experience and repeated practice

- Textual interaction

- Oral interactions

- Mentoring and disciplinary participation

- Shifting roles within a genre network, and

- Resource availability

Throughout the development and delivery of PROV 506/507, course developers/instructors strove to integrate these four domains of developing genre knowledge by designing an innovative curriculum arc, exposing students to authentic writing and communication opportunities that required the application of specific resources and strategies evidenced in Tardy’s case studies. However, in order to truly enact the curriculum arc, designers also needed to do the work of developing a clear and grounded pedagogical approach.

Contributing an applied linguistic pedagogical perspective, it was determined that the formal knowledge domain of Tardy's model would best be enacted with an EAP approach to language teaching and learning. Such an approach, according to Hyland, acknowledges that language challenges “cannot be addressed by some piecemeal remediation of individual error. Instead, EAP attempts to offer systematic, locally managed, solution-oriented approaches that address the pervasive and endemic challenges posed by academic study to a diverse student body by focusing on student needs and discipline-specific communication tasks” (4). Further, due to the multidisciplinary nature of the course (i.e. BRIDGE students enrolled in the course represented a wide range of degree programs), it was determined that the EAP approach would focus on English for General Academic Purposes (EGAP) rather than English for Specific Academic Purposes (ESAP). Finally, with regard to the EGAP approach to writing in the disciplines, the instructors decided to stabilize the genres under study, extending Schryer’s articulation of all genres as “stabilized-for-now” by fixing them in time and place without explicitly discussing their socio-rhetorical nature (208). As such, instructors used specific genres as targets of instruction in order to give the target population—international multilingual students in this particular program—a direct look at the conventions of academic discourses and genres of the U.S. academy as well as a more stable entry point into their disciplinary communities. This stabilization-for-now approach was particularly prevalent in the first semester of the course, establishing the groundwork for students to begin to perform as active members of their disciplinary discourse communities. Then, as students built their genre competence, the second semester shifted the focus from “noticing” the conventions of typified academic genres to engaging in authentic social action by enacting the genres of a specific site of activity (Cheng 86).

Graduate Communication across the Disciplines: Course-level Projects and Assignments

The first semester of the sequenced, two-term course, PROV 506, comprised two major projects, the Grammar of Academic Writing project (GAW) and the Graduate Student Writer Handbook project (GSWH). With an EGAP approach that focused on situated features of genre, these projects were designed to require that BRIDGE students notice the “conventions of structure, reference, and language” of academic journals and journal articles in order to begin to recognize the ways in which the values of a discipline inform or drive the formal features of academic genres (Linton, Madigan and Johnson 68-75). These assignments exposed BRIDGE students to the conventions and linguistic features of academic writing in the Western academy by asking them to engage in rhetorical and formal analyses of academic journals and journal articles. To deepen their analysis and extend it beyond a report of fixed rhetorical and formal features, the GSWH project required students to design an online graduate writer’s handbook for other international students in their graduate program, introducing these imagined future peers to the disciplinary discourse community, its values, epistemologies, rituals, and conventions. In effect, the first half of the course was intended to address what Hyland and Swales recommend in terms of raising students’ consciousness around academic genre sets and salient linguistic conventions of their individual discourse communities through an exploration of professional organization/communication within the larger activity system of the US academy.

By asking students to identify linguistic features, such as phrase formation and word structure, as well as conventional features of journal articles in their disciplines, the GAW project focused heavily on the development of the formal knowledge domain. The GSWH project continued to develop this domain by attending specifically to academic language while adding to it explicit instruction of both process and rhetorical knowledge. Process knowledge was developed in particular through attention to composing processes, while rhetorical knowledge was addressed through the creation and development of a handbook that responds to a real need of particular students in a specific context. Additionally, throughout these first two projects, students were provided with a variety of textual resources and were encouraged to draw on their prior experiences as they developed their expertise.

The second half of the year-long course, PROV 507, focused on two major projects: The Graduate Language Portfolio Project (GCLP) and the Multidisciplinary Colloquium Project (MCP). Here, like the first semester projects, both the GCLP and the MCP aimed to move students along an EGAP to RGS-informed curriculum arc, balancing language content and composition objectives. In the GCLP, students led seminar-style discussions relating to academic articles, wrote summary and response essays, and developed discussion questions relating to the seminar topic. With its attention to vocabulary building and question formation strategies, this project built formal knowledge awareness while continuing to ask students to read rhetorically in light of the goals and values of their discipline. This project further focused on process knowledge by allowing students the opportunity to revise/edit and resubmit as they received and responded to individual feedback on text annotations, summary/response writing, and seminar planning documents.

Also in the second term of the year-long sequence, the MCP was designed to prepare students for an authentic professional conference presentation at the CISA Multidisciplinary Colloquium, where students presented secondary research (conducted in English and in their native language) that addressed an interdisciplinary or cross-cultural question in their discipline to an audience of peers, faculty, and administrators from across the university and community. The genre set that generated the final conference presentations included the following: Topic Proposal, Research Question, Annotated Bibliography, Literature Review, Conference Proposal, Bilingual Abstract, Conference PowerPoint, Notes & Handout and Conference Presentation (See Table 2 for the assignment sequence and outcomes). This final project allowed students to move beyond consciousness raising to exploring their disciplines in response to an authentic, rhetorically-situated task. Throughout the project, students explored process knowledge by examining how various genres (conference proposal, literature review, abstract, presentation, etc.) are taken up within a genre system, developed rhetorical knowledge by engaging in an authentic writing activity, and developed subject-matter knowledge by examining a topic from their own discipline in relation to the interdisciplinary and cross-cultural questions posed in the CFP. The MCP not only gave students the opportunity to interact with the five domains of disciplinary expertise through enacting the authentic genre system of the professional conference presentation, but it also asked students to manipulate the genre set by disrupting its monolingual assumptions; students were required to write their conference presentation abstracts in both English and their native language, locate and include at least two non-U.S. sources in their literature reviews, include bilingual slides in their final PowerPoint presentations, and present sections of their conference presentations in a language other than English. This expectation for the MCP pushed students (and attendees) to question the invisible value systems, epistemologies, and social rituals of professional organizations and conferences, encouraging them to begin to view genre as a tool for social action in addition to a functional product of a communicative act.

|

The Grammar of Academic Writing (semester 1, weeks 1-7) |

Writing in the Disciplines: The Graduate Student Writer Handbook (semester 1, weeks 8-15) |

The Graduate Classroom Language Portfolio (semester 2, weeks 1-8)

|

The Multidisciplinary Colloquium Project (semester 2, weeks 3-15) |

|

Identifying:

|

Identifying:

|

Participating in Graduate Seminar:

|

Participating in Academic Conference:

|

Table 2. Graduate Communication across the Disciplines Curriculum Overview

In the development of these assignments, course designers incorporated the formal, process, and rhetorical domains; explicit attention to the subject-matter domain was no less important, yet proved more difficult. Recognizing that writing/language approaches to developing disciplinary expertise are often criticized for their inability to attend to the development of subject-matter knowledge, course developers sought alternative approaches to provide explicit subject-matter feedback within the course design itself. To accomplish this, course creators developed a peer mentorship initiative, the BRIDGE Scholar program. Each BRIDGE student was paired up with a peer in his/her same graduate program in order for the Scholar to offer content feedback to the BRIDGE student’s writing and to serve as an academic/professional partner, supporting the beginning stages of a Legitimate Peripheral Participation model (Lave and Wenger). These mentors provided emerging international scholars with an opportunity to observe and participate in the language, conventions, and ways of knowing/doing of their newly-acquired community.

In the end, once all of these programmatic support and infrastructure pieces were established, the PROV 506/507 intervention course was finalized and aimed to support BRIDGE students in their pursuit of several course-level objectives. Specifically, successful students in the course needed to be able to demonstrate the ability to:

- engage in select, authentic graduate-level written/oral communication tasks.

- contribute to and participate in their discipline-specific communities of practice.

- analyze and adapt to the rhetorical needs of a particular project.

- explore varied ways of communication.

- incorporate secondary source material appropriately (including scholarship in other languages).

- choose appropriate genres and target audiences.

- recognize and challenge the utility of genres within a larger genre system.

- understand research methodologies and conventions in U.S. academic writing.

- include multilingualism strategically in research and communication activities.

- grow awareness of language usage through

- editing writing for correctness of syntax and appropriateness of diction.

- refining self-correction techniques for resolving individual patterns of error.

- oral communication skills practice, in the context of graduate-level, discipline-specific discourse conventions.

The Research Study

Although PROV 506/507 was conceptually anchored in theoretically-informed pedagogical approaches put forward by Composition and Applied Linguistics, course designers/instructors recognized the importance of studying the extent to which (and, if at all, the ways in which) this particular enactment of Tardy's model worked in practice with this population. In fact, at the outset, instructors sensed that the BRIDGE students were pushing against the planned course structure, questioning the relevance of the projects, assignments, and activities. Reflecting on the various pressures BRIDGE students were contending with during this first-year program, the instructors acknowledged the complex and unsteady chain of activity systems at the local and institutional levels. Within this dynamic context, the classroom appeared to emerge as a site of tension for both faculty and students.

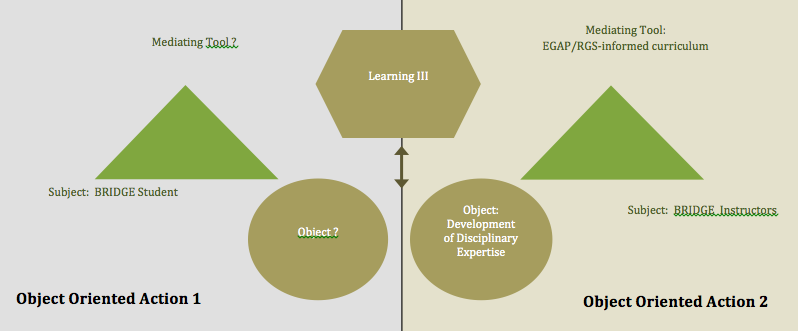

Given the layers of negotiation these students were involved in (cultural, social, linguistic, academic, etc.), the instructors wondered whether there was a locus for the tension all were experiencing in the classroom interaction, compelling the instructors to investigate the dynamics of the contact zone. To do so, Cultural Historical Activity Theory was employed to help illuminate the activity system of the PROV 506/507 course by mapping the two Object-Oriented Actions (OOAs) that were simultaneously unfolding (see Figure 2). The two Object-Oriented Actions in Figure 2 represent the activity system of the PROV 507 course, mapping the instructors’ and students’ goals, or objects, for the course, and the mediating tool through which each of the subjects planned to achieve the defined goal. Diagramming the two OOAs provided a tool for thinking through students’ and instructors’ objectives, making clear that while the instructors had identified the objective as wanting to support BRIDGE students in the process of developing disciplinary expertise through the EGAP/RGS-informed pedagogical intervention course (OOA2), it was not clear what the student-subjects’ objectives were or what mediating tool they were relying on to meet that objective (OOA1). Applying the CHAT analysis to the classroom system highlighted the potential for what Engeström described as a space for “Learning III,” a rich dialogic zone that offers an opportunity to synchronize the objects in the two OOAs.

Figure 2. Perceived Tension in PROV 506/507 Contact Zone

Figure 2. Perceived Tension in PROV 506/507 Contact Zone

After utilizing the CHAT framework to pinpoint what was undetermined in the activity system—BRIDGE students’ objects and mediating tools—the teacher-researchers set out to systematically investigate the source of tension and the extent to which students' objects and mediating tools aligned with the EAP/RGS-informed pedagogical approach enacted in the PROV 506/507 curriculum. This motivation led to two specific research questions:

- How successful (if at all) is the PROV 506/507 intervention course at meeting institutional expectations for BRIDGE student success, including goals for students’ English language proficiency and degree program academic success?

- How, and in what ways, are BRIDGE students developing disciplinary expertise in the context of the EGAP/RGS-informed pedagogical intervention? How are they articulating their own expectations for the course (i.e. the object in OOA2)? How are they articulating their own method/process for achieving course outcomes (i.e. the mediating tool in OOA2)?

Here, focus has been paid primarily to a discussion of the second research question in order to illustrate the extent to which and the ways in which students’ perception of their own developing disciplinary expertise throughout the PROV 506/507 course aligned with Tardy’s model.

Participants

Study participants included twelve Master’s level and two Ph.D. level international, multilingual graduate students. All participants were affiliated with the BRIDGE program in some way: four were current BRIDGE students, two were former BRIDGE students, one was a non-BRIDGE international student enrolled in the intervention course, and five were first-year BRIDGE Scholars. Participants reflected a wide range of academic interests in a variety of disciplines at Mason, including: Conflict Analysis and Resolution, Bioinformatics, Computer Forensics, Arts Management, Information Technology, Software Engineering, Geoinformation Science, Public Policy and Music Education.

Measures

Over the course of one year, Spring 2012-Spring 2013, a multi-data set for each of the seven BRIDGE student participants was collected, including: incoming and exit English language proficiency scores, overall and individual course GPAs,{5} sample student writing, and two semi-structured interviews.{6} Interview data was coded for emerging themes by the two instructors and the third outside researcher (Strauss and Corbin). The interview questions were designed to address four overall themes: 1. Students’ overall experiences in the CISA BRIDGE program; 2. Students’ conceptions of “good” graduate-level writing at the university, in their fields, and in the workplace; 3. Students’ self-perception of academic writing and academic English language goals/development; and 4. Students’ self-perception of their process/method for developing disciplinary expertise throughout the PROV 506/507 intervention course and in their degree programs.

Findings and Analysis

1. How successful (if at all) is PROV 506/507 at meeting institutional expectations for BRIDGE student success, including goals for students’ English language proficiency and degree program academic success?

In terms of meeting the institutional demands related to student English language proficiency and academic standing, results of the study indicate that PROV 506/507 may have contributed to BRIDGE student success on a few different levels. The majority of students in the course were able to raise their scores on the commercial, skill-based English language proficiency test to a B2 level or higher, satisfying this requirement for provisional to full admission.

Only three students in the course did not meet the language proficiency score requirement, scoring at the B1+ level rather than the B2 level; however, these students were allowed to use the disciplinary writing and oral communication assignments from the course as a substitute measure for the language proficiency test. In other words, because these students had demonstrated the ability to write and communicate in the disciplinary conventions of their field throughout the year-long course and because one of the instructors was a language specialist who could “certify” that requisite language proficiency had been achieved, the instructors were able to build a case to the university administration for a process to override the skill-based English language proficiency exit exam scores with these course-based demonstrations as/if necessary.

The other institutional measure of BRIDGE student academic success was determined by students’ overall and degree-course specific GPAs. In this respect, the average GPA for the international graduate student-participants (not including the BRIDGE scholars) was a 3.56. Additionally, the students were earning primarily A’s in their degree courses, which indicated a high level of academic success for students enrolled in the CISA BRIDGE program.

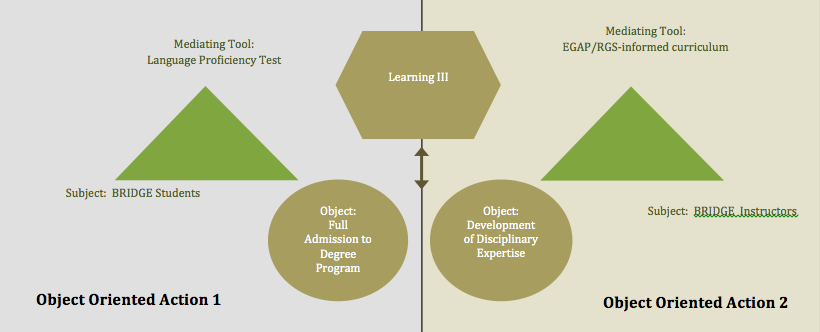

2. How are BRIDGE students articulating both their expectations for the course (i.e. the object in OOA2) and their own method/process for achieving perceived course outcomes (i.e. the mediating tool in OOA2)? How, and in what ways, are BRIDGE students developing disciplinary expertise in the context of the EGAP/RGS-informed pedagogical intervention?

BRIDGE students’ expectations for the course (i.e. the object in OOA2) differed from the planned expectations articulated in the curriculum arc (i.e. the object in OOA1) in that students perceived PROV 506/507 as an intervention to prepare them for the end-of-year English proficiency test. In other words, since all BRIDGE students were required to pass the general, skill-based language test in order to gain full admission into their degree programs—a test that does not aim to measure students' development of academic English and/or development of disciplinary expertise—they assumed that the intervention course would be language test preparation. Thus, unlike the ways in which the EGAP/RGS-informed curriculum arc had embedded language teaching/learning as a way into the intersectional nature of disciplinary knowledge development, the end-of-year high-stakes test isolated language skills in an inauthentic and non-academic context wherein BRIDGE students needed to demonstrate adequate English proficiency across discrete linguistic domains. In fact, not only was the final language assessment not aligned with the ways in which students had been experiencing language teaching/learning throughout the intervention course, but also, the final skill-based assessment did align with what students came to the intervention course expecting to experience; in other words, the discrete, skill-based, non-integrated approach to language learning and assessment present on the final test was more recognizable (and, by default, given greater value) by BRIDGE students. Students questioned the degree to which the PROV 506/507 curriculum arc and pedagogical approach had prepared them to succeed on this final exam. So, while the instructors and course designers were focused on developing disciplinary expertise, both the histories of the students and the requirements of the institution viewed language as outside of (or perhaps a precursor to) disciplinary knowledge. Indeed, analysis of the data revealed that a significant part of the tension in the students’ reaction to the course lay in the different (and sometimes conflicting) demands of the institution, the students, and the instructors themselves. For example, several weeks into the course (after the course goals had been presented, discussed, and enacted in the classroom) when the first cohort of students was asked what they envisioned as their goals for the course, the following list of course outcomes were collaboratively articulated:

- improve my oral English proficiency

- express my ideas clearly

- write more accurate sentences

- write, read, speak English in an American academic context

- improve my reading skills

- express my intention and meaning clearly

- develop my listening skills

- understand content and deliver messages/content easily

As indicated in these responses, BRIDGE students were understandably preoccupied with developing their expertise in the domain of formal knowledge, neglecting to articulate motivation for developing in the rhetorical, process, or subject-matter domains. They appeared to suffer from language (and genre, perhaps) anxiety, and this fixation on discrete English language proficiency development was understandable given its institutional value (i.e. full admission to degree programs). Further, these exit English language proficiency tests were familiar genres, whereas the processes, rhetorical choices, and genres of academic writing were not. In fact, it was evident that BRIDGE students did not yet have the graduate academic language or the awareness of graduate-level academic writing culture/conventions to be able to interpret the genre-based, EAP course-level approach presented in PROV 506/507. The result of these layers of unfamiliarity and the overwhelming concern for English language proficiency development led the majority of BRIDGE students to perceive the intervention course, in the beginning, as a skill-based communicative English language course and nothing more/other.

In order to explore such general findings around BRIDGE students’ anxiety of English language proficiency development more fully, researchers turned to participant interview data. Here, with regard to the effects of language assessment requirements on students’ ability to focus on other domains of genre development, interviews with two students—Alice and Yasmin—illuminated concerns characteristic of the larger population studied. In the interview with Alice, for example, she spoke specifically about the pressure she felt to perform on the language proficiency test despite her marked success in the intervention course. Specifically, her anxiety around the exit English language proficiency test hindered her ability to fully engage with the non-formal aspects of the curriculum. In her first interview, Alice emphasized how worried she was “about [her] future” because her BRIDGE program advisor cautioned her that without a B2 level exit score, she would not be admitted to her degree program. Yet, at the same time, her departmental advisor in the Arts Management program contradicted that message, insisting that Alice not spend time worrying about the exam and, instead, focus on completing the BRIDGE program courses successfully. “That’s why I was under a lot of pressure,” Alice explained; “If there’s one thing I can change in BRIDGE program, I’ll take out this exam. Because I wrote a lot and took different courses that year, which had enhanced our abilities. We took graduate courses together with BRIDGE courses. We could use what we learned from BRIDGE courses in our graduate courses all the time. So that exam should not be used.”

Throughout the interviews with Alice, it was clear that she appreciated the transfer of skills and knowledge between the pathway courses and her disciplinary courses; however, she felt wedged between the values and resulting programmatic/institutional policies of a pathway program that strictly enforced testing/GPA policies and a graduate unit that was more flexible and open to evaluating students on an individual basis. In fact, though the instructors explained to Alice that many graduate units (including hers) were willing to consider written waivers from the pathway faculty (to override language test scores at the end of the year), she, like most BRIDGE students, felt unsure about what advice to trust the most and this only legitimized the students’ general heightened anxiety around language proficiency requirements overall. While Alice felt that she had to prioritize her language development over her rhetorical, process, or subject-matter progress, she was still able to manage the rigor of her degree courses with much success as was evident in her 3.65 GPA and general feeling of academic support in her graduate coursework.

A second example of interview data that indicated the ways in which language anxiety influenced BRIDGE students’ ability to focus on other domains of genre development was evident with Yasmin who, like Alice, exhibited a similar preoccupation with grammatical accuracy and language proficiency development throughout the semester. Although she did excel in her understanding of the rhetorical, process, and subject matter domains of her disciplinary discourse, and she felt that she knew “the conventions of writing, how we apply writing in computer science and writing in engineering,” she still felt inadequate as a scholar in her discipline because of her perceived lack of language proficiency and her desire for “perfect” grammar, stating “I still need improvement. Grammar is not perfect even now.”

In many ways, such interview data helped the instructors to better understand and appreciate PROV 506/507 students’ experiences and anxiety with regard to the language test and how it shaped their sense of priorities and exigency in the intervention course. Students’ anxiety around language proficiency illuminated the tension perceived at the onset. For the students in OOA1, for example, achieving a B2 level was the most important factor in realizing their goals (or objects) of being fully admitted to their degree programs, which prioritized the proficiency test among other academic goals in the pathway year. In stark contrast, the instructor-subjects in OOA2 had goals for the course that did not center on teaching to the language test but rather on supporting international, multilingual scholars in language development through a situated learning curriculum and the uptake of specific genres within defined activity systems (see Figure 3). In short, while both the students and the faculty aimed to achieve language teaching/learning goals by the end of the year, the seeming invisibility of the language teaching and learning approach (i.e. embedded in the genre-driven system) made it difficult for PROV 506/507 students to identify progress toward this high-priority learning goal, thus increasing student anxiety around both language and genre throughout the year. With the language test as the student-subjects’ mediating tool, they could not recognize the full curriculum arc and the general course goal of developing disciplinary expertise.

Figure 3. CHAT Analysis of Intervention Course Tensions

The Uneven Development of Genre Knowledge

Though language proficiency benchmarks served as gatekeepers to individual programs and while students understandably felt significant pressure to "increase" their language proficiency during their pathway year, student-participants did seem to manage the work of actively pursuing the development of disciplinary expertise in their own ways, depending on their prior experiences/knowledge and in the process of contending with short-term and long-term goals. Thus, although the pressure to perform on the test may have affected (even limited) the extent to which the students efficiently participated in the domains of genre knowledge beyond the formal (including the rhetorical, process, and subject-matter domains), BRIDGE students did demonstrate progress in these other areas. Certainly, participants from this population of non-matriculated, graduate pathway students did take up different domains of knowledge based on their particular experiences and needs, extending what Tardy found in a previous study.

In order to mitigate the reluctance faced by the four students in Tardy's study when required to engage in genre-based work that was not connected to their own immediate or long-term interests or needs, all PROV 506/507 course projects—especially project 4, the Multidisciplinary Colloquium Project—aimed to give students authority and agency to the extent possible. To ensure that students from across the disciplines would gain a valuable, language-in-context and genre-in-action experience, the BRIDGE program and PROV 506/507 course creators developed the CISA Multidisciplinary Colloquium, the goals for which were fairly explicit: to create a space at the institution for international graduate students to participate in the university community, to foster BRIDGE students’ exploration and engagement in their disciplinary communities, and to provide university faculty/staff with an opportunity to validate these emerging international scholars’ multilingualism and global perspectives. In sum, the aim was for students to feel invited and authorized to participate in the CISA-sponsored conference and to simulate an authentic conference proposal/presentation process so that BRIDGE students would gain confidence when encountering additional call for proposals in the future.

Through the design of the MCP project, course designers had hoped to counterbalance authority and agency constraints as well as respond to what Freadman has recognized with regard to the potential for inauthentic classroom exercises to delegitimize genre uptake by "sever[ing] them from their semiotic environment” (qtd. in Bawarshi and Reiff 87). The MCP project gave students an authentic experience with an academic/professional genre system, the underlying monolingual values of which they were asked to challenge through reading, writing, and speaking in their own native languages in addition to academic English.

In response to the CFP and other course-based attempts to provide authentic writing and communication tasks, student-participants did appear to struggle to take on new academic identities throughout the year. When interviewed about their experiences in the course and with the curriculum, students in the larger study were mostly absorbed with the ways in which they felt the course equipped them (or did not) with the disciplinary expertise that would authorize their participation in their degree courses. As students reflected on their development in the course, they either implicitly or explicitly tied their confidence and academic readiness to one or more of the four domains of genre knowledge. Even though anxiety around developing their expertise in the formal domain was heightened as a result of the end-of-program language proficiency test, student-participants did recognize the value of the other domains in helping them develop the expertise that they felt was essential to their integration into their degree programs.

For example, Yasmin is a student who, despite her noticeable language anxiety, showed evidence of being able to integrate all four domains of genre knowledge throughout the year, which she directly tied to her developing academic voice and identity. In her post-course interview, she connected her authority to speak with her understanding of particular genres in her field: “Now,” she said, “I know if someone ask me how to write a paper and how you do critiques, I’m not dumb now. I can say something. So I think in that sense, I rated myself 85 to 90 [out of 100]. I’m not perfect even now. English is not my first language. I still need improvement, but I have been trying hard.” In a sense, it seems that Yasmin felt that her genre knowledge, or her knowledge of the conventions of writing in Computer Science and Engineering, helped regulate her anxiety about her English language fluency. For Yasmin, she felt that the genre knowledge she gained in the intervention course helped her to do better than her non-BRIDGE graduate peers in other graduate courses. Interview data suggests that, for Yasmin, working through the MCP research process helped her establish a clearer sense of her own position within her field:

We had to give a conference presentation, so I had went through it. I read many research paper; I studied a lot. From that, I went to the conclusion that in order to write in my field, first, I need to find out what the researchers have done so far. So we need to discover what’s going on in our industry; discover everything; analyze it; put on your argument: is it right or wrong? is it completely make sense? What contribution you can do on that one? Then you can make your contribution and make it happen in the near future. It’s the writing procedure in general.

Interestingly, for Yasmin, working with her BRIDGE Scholar and preparing for the MCP conference presentation led her to change her degree program from Computer Science to Software Engineering. She realized that “computer science is a bit too theoretical” and that she was looking for more applied work. For her, the EAP/RGS-informed intervention course gave her a range of skills that she was able to successfully integrate to develop a clearer sense of her own disciplinary interests—moving her from nascent knowledge to the nexus of genre knowledge—and, by extension, to gain more confidence in her position as an active member of her degree program.

In contrast, Ali’s ability to function within the different domains was somewhat mixed. On the one hand, his interview data suggests that he appreciated the way that instructors were “focusing on writing in our discipline;” however, he struggled to do the writing because of his perceived unfamiliarity with the subject-matter domain: “I need more information about my field to write about. If I learn just how I write in my discipline, but I don’t have the knowledge to write about, so I can’t write about anything. It’s not viable knowledge.” To be sure, Ali’s inability to access the requisite subject-matter knowledge made the approach to the course both difficult and uncomfortable for him. Despite this challenge, he was keenly aware of the kinds of process knowledge addressed throughout the course:

If I came from my country, if we have 10 source and use 10 source, I’d try to read 10 source, but I’ll not write summaries, annotated the paper I read. I’m sure I’ll face difficulties when I start my research. But now when they give this tips, they show us how to do these research. First, read articles; write summaries; write notes; make it annotated. So now when I start writing the project, I have my own resource; I can go back. If I just have the literature resource, I’ll feel loss. And I appreciate this method because I’m feeling more confident.

Here, Ali explicitly discussed not only the process knowledge that he gained from the course but also the ways that this knowledge could transfer to his other courses and projects in his discipline. His focused effort in this domain seemed to give him both skills and confidence to approach writing in his discipline despite his limited ability to access the subject matter. So while Yasmin seemed to equate the procedural knowledge she gained through the MCP as essential in building her subject-matter knowledge, Ali appreciated the research experience as an exercise in research skill-building without necessarily developing his subject-matter knowledge. For him, the research process itself was an essential tool in building his “academic readiness” guiding him towards his degree program.

As Yasmin’s and Ali’s interview data exemplify, BRIDGE students did struggle and succeed in their efforts to develop genre knowledge across domains. However, of note, interview data with one student—Hebah—indicated an interesting departure from these general findings. When asked to reflect on her own growth across domains, Hebah explicitly stated her desire to develop not just academic genre knowledge but also professional/workplace genre knowledge. Specifically, unlike the other students in the study, Hebah expressed serious goals with regard to her professional identity and development as a researcher and bioinformatician. When prompted to reflect on her learning experiences in the PROV 506/507 course, Hebah described a level of confidence with procedural and rhetorical knowledge in her degree courses and was pleased to be “able to actually have the flow and knowing how to analyze the scholarship and extract ideas more easily.” She did, however, wish that she had been “trained in other genres” that were more common in Bioinformatics. For her, while the situated task of the conference proposal allowed her to engage in an authentic, academic genre network, she did not perceive the MCP experience to be close enough to her own professional development needs. The clarity she had about her career goals left her feeling a little isolated from the rest of her BRIDGE peers, many of whom, according to her, “were just fresh graduates from their undergraduate programs.” In comparison with others in the course, Hebah believed that her subject-matter knowledge was adequately advanced because she “had actually worked as a scientific researcher [in her home country] and wanted really to incorporate what [she] learned in the program to [her] workplace.” Therefore, with regard to the MCP, Hebah reflected, “the idea of a whole project is great, but getting exposed to other genres [outside the conference presentation genre network] would be helpful also.” For Hebah, who was already familiar with the discourse community she was entering, disciplinary expertise meant comfort with the specific Bioinformatics genres.

Unlike Yasmin and the other BRIDGE student participants who seemed to appreciate the intersectional nature of the four domains of genre knowledge development, Hebah seemed to perceive the four domains as preliminary steps to gaining the kind of disciplinary expertise that she sought as an experienced professional in her field. This interview data challenged the researchers/course designers to consider if and how PROV 506/507 might incorporate professional/workplace genre development goals in addition to the established general academic genre development goals in future iterations of the course; further, Hebah’s reflections have provided reason to consider the potential impact of a more ESAP/RGS-informed approach to PROV 506/507 in order to meet the needs of such professional, experienced students like Hebah in future terms. Though such an approach is not fitting given the multidisciplinary reality of current course enrollments, perhaps such an approach will be feasible as enrollments grow and discipline-specific sections of the course are offered.

Conclusion

This program profile illuminate the ways in which complex institutional demands, personal pressures, and instructor goals interact and affect students’ participation in one theoretically-based, integrated curriculum. Though PROV 506/507 appears to be successful from an institutional perspective with regard to the development of students’ language proficiency and in terms of students’ academic success, the tension in the course stemming from these external pressures, particularly the pressure of the language test, may have limited the extent to which students were able to participate in the genre systems and to develop their own disciplinary expertise. Although, as the exit interviews revealed, students did eventually gain confidence in at least one of the four domains of disciplinary/genre expertise, their focus on the skill-based language proficiency test (the mediating tool), hindered their ability to access the EAP/RGS-informed curriculum and to recognize the intersectional nature of developing disciplinary expertise.

These findings have important implications both institutionally and programmatically. At the broader level, institutions may want to think carefully about their use of large-scale, commercially-based language skills tests as additional prerequisites when students have already been conditionally admitted into their programs. These tests, while sometimes useful in determining general language proficiency, can be problematic when they are not tied explicitly to the goals of intervention courses and programs. Rather than relying on such measures, programs and institutions might consider developing local language assessments, constructed with the needs of the students, objectives of the language/composition interventions, and goals of the institution in mind.

In many cases, however, these types of large-scale structural changes to the institutional requirements may not be viable. If, institutionally, large-scale language tests are going to be used, then it is important for instructors to talk explicitly about the language-genre connection, to make the language goals of the genre-based classroom visible to the students. In particular, with regard to the EAP-RGS approach used in PROV 506/507, this study has led to a reexamination of genre in its relationship with language teaching/learning. For, as is evidenced in the language proficiency and academic success data, although the students did not recognize their own language development progress, the course did, nonetheless, aid students in meeting institutional requirements for progression to full degree status. The goal for instructors, then, must be to make explicit this connection between language development and growth in genre knowledge so as to ease student anxiety surrounding institutional requirements while at the same time developing language and disciplinary expertise. If these domains of expert knowledge are presented explicitly to international, multilingual graduate writers as inextricably linked, student anxiety around language proficiency may subside, freeing them up for more efficient and deeper genre uptake.

In fact, in the context of this language-supported, genre-based approach to a multilingual graduate writing intervention course, the course designers/researchers have come to greatly appreciate Gentil’s persuasive claim regarding the evolution of theory building in composition studies and applied linguistics when he states that “as researchers in each field have endeavored to develop expanded views of genre knowledge and language proficiency from more sociological perspectives, they have come to characterize the two concepts in nearly identical ways” (Gentil 13). Through the genre-based, EAP approach to the graduate writing course, all English language teaching and learning is driven by the social need to communicate academic information in authentic, genre networks that are dynamic and flexible. In this context, the focus on English language teaching and learning cannot be on language skills but rather on language strategies; for it is in the dynamic genre network that language usage must be strategic, responsive, and flexible. It is also through this approach that language skills become meaningfully operational as they are expanded and adjusted in authentic communication tasks within and across disciplinary discourse communities, according to evolving genre-based expectations for appropriate or acceptable communication. It is this area—the focus on the teaching and learning of English as an integrated, responsive, and sophisticated type of what Gentil terms strategic competence—that we look forward to exploring more in the coming iterations of this course. In the meantime, to better address these conflicting tensions, composition and language instructors should be explicit in their understanding and communication of the relationship between genre knowledge and language acquisition, and this relationship must be continually discussed and reinforced in the classroom. By explicitly discussing the ways that working in and through genre can improve language skills, instructors can mitigate students’ anxiety regarding the language proficiency while at the same time maintaining the goals of the course and developing students’ genre knowledge.

Finally, in light of the growing interest and concern over internationalization in U.S. institutions of higher education, it is critical to examine the tension between a language-supported approach to internationalization and the more traditional, narrowly-defined notions of “strategic internationalization;” for, as institutions and departments work to increase international enrollments, it is important to support an inquiry-based, data-driven approach to comprehensive internationalization. In the case of this study, in the context of this program within this institution, it is only through this research process and the researchers’ and course designers’ theoretical knowledge that they have been able to more deeply consider and categorically examine the ways in which their pedagogical approach to genre and language instruction has been received and interpreted by their international graduate pathway students. And it is through this process that they are now able to make programmatic and course-level revisions as well as to communicate these findings back to upper administration and to their respective fields. This kind of commitment to internationalization—a commitment to studying the student and the faculty experience in composition and language and other content classrooms—is critical to a healthy, truly comprehensive approach to thoughtful, long-term internationalization. For as Hudzik suggests, comprehensive internationalization “is a commitment, confirmed through action, to infuse international and comparative perspectives throughout the teaching, research, and service missions of higher education” (6). In order to foster innovative instruction and responsive interventions that meet the linguistic, academic, and writing development needs of this growing sub-population of graduate students, institutions must encourage research that will inform teaching and learning. They must also be willing to recognize these international, multilingual graduate students as whole beings who bring their own sets of tensions and expectations to even the most thoughtfully constructed curriculum/classroom by examining such points of tension; appreciating the complexities, contradictions, and contributing factors that exist in those spaces; and communicating suggestions for data-driven interventions to our respective programs, institutions, and fields.

Notes

- In this article, Tardy’s four domains of “genre knowledge” are used as the framework for understanding students’ development of “disciplinary expertise,” originally theorized by Beaufort. In analyzing four multilingual graduate students, Tardy found that these students’ disciplinary expertise emerged through their experiences building genre knowledge, which converged subject-matter knowledge, rhetorical knowledge, procedural knowledge, and formal knowledge. (Return to text.)

- Matriculation requirements were determined by program (i.e. decentralized admission processes), ranging from an overall TOEFL© score of 88-100. (Return to text.)

- The BRIDGE program operated on two tracks, determined by graduate departments’ requirements for exit language proficiency scores. BRIDGE Gold required students to enter the program year at the B2 level on the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), which is an entrance equivalent to TOEFL iBT ©87-99 and exit equivalent to TOEFL iBT ©100-109. BRIDGE Green required students to enter the program year at the B1+ level, which is an entrance equivalent to TOEFL iBT© 80-86 and exit equivalent to TOEFL iBT© 87-99. (Return to text.)

- The coursework included in Table 1 reflects the second iteration of curriculum, revised after the pilot year when it was determined that the Graduate Writing in the Disciplines course should take on the practical listening/speaking components of the, then separate, interpersonal communications course. Thus, the resulting course, PROV 506/507: Graduate Communication Across the Disciplines, became a more comprehensive, integrated skills course. Further, it was decided that this course be year-long instead of semester-long and it was determined that a second support course, Graduate Study Preparation for International Students, should also be year-long. (Return to text.)

- While we recognize that data on GPA provides a limited means for measuring academic success, institutions rely on these types of numerical evaluations, and they are, therefore, frequently used in studies determining programmatic efficacy and student academic success (Daller and Phalan). (Return to text.)

- Interviews took place at the beginning and the end of the intervention year. All interviews were conducted by an international graduate student research assistant. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

ACE: American Council on Education. Mapping Internationalization on U.S. Campuses. Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education, 2012. Print.

Bawarshi, A., and M.J. Reiff. Genre: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research and Pedagogy. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2010. Print.

Beaufort, A. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for Universtiy Writing Instruction. Logan, UT: Utah State Unviersity Press, 2007. Print.

Belcher, D. The Apprenticeship Approach to Advanced Academic Literacy. English for Specific Purposes 13 (1994): 23-34. Print.

Bevis, T.B., and C.J. Lucas. International Students in American Colleges and Universities. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Print.

Casanave, C.P. Writing Games: Multicultural Case Studies of Academic Literacy Practices. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002. Print.

Cheng, An. Understanding Learners and Learning in ESP Genre-Based Writing Instruction. English for Specific Purposes 25 (2006): 76-89. Print.

Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. Basics of Qualitative Research. London, UK: Sage, 2008. Print.

Daller, M., and D. Phelan. Predicting International Student Study Success. Applied Linguistics Review 4 (2013): 173-193. Print.

Douglas, D. Assessing Language for Specific Purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Print.

Engestrom, Y. Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an Activity Theoretical Reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work 14 (2001): 133-156. Print.

Foskett, N. Global Markets, National Challenges, Local Strategies: The Strategic Challenge of Internationalization. Globalization and Internationalization in Higher Education. Ed. F. Maringe and N. Foskett. London: Continuum, 2010. 35-50. Print.

Freadman, A. Anyone for Tennis. Genre and the New Rhetoric. Ed. A. Freedman and P. Medway. Bristol: Taylor and Francis, 1994. Print.

Gentil, G. A Biliteracy Agenda for Genre Research. Journal of Second Language Writing 20 (2011): 6-23. Print.

Hudzik, J. Comprehensive Internationalization: From Concept to Action. Washington, D.C.: NAFSA, 2011. Print.

Hyland, K. Genre and Second Language Writing. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004. Print.

Lave, J., and E. Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Print.

Linton, P., R. Madigan, and S. Johnson. Introducing Students to Disciplinary Genres: The Role of the General Composition Course. Language and Learning Across the Disciplines 1 (1994): 63-78. Print.

Maringe, F., and P. Gibbs. Markeing Higher Education: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2009. Print.

Open Doors. Report on International Educational Exchange. 2014. International student enrollment trends, 1949/50-2012/13. Web. 20 August 2014. <http://www.iie.org/opendoors>.

Shryer, C. Records as Genres. Written Communication. 10.2 (1993): 200-234. Print.

Swales, J. Further Reflections on Genre and ESL Academic Writing. Paper Presented at the Symposium of Second Language Writing. West Lafayette, IN, 2000.

Tardy, C. and J. Swales. Form, Text Organization, Genre, Coherence, and Cohesion. Handbook of Research on Writing. Ed. C. Bazerman. New York, HY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2008. 565-581. Print.

Tardy, C. Building Genre Knowledge. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2009. Print.

The Development of Disciplinary Expertise from Composition Forum 31 (Spring 2015)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/31/george-mason.php

© Copyright 2015 Anna S. Habib, Jennifer Haan, and Karyn Mallett.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 31 table of contents.